Introduction: Hyperkinesia due to dysfunction of the basal ganglia can be caused by a number of predominantly vascular and (para)infectious as well as endocrine diseases. In the following, we report the rare case of a patient with type 2 diabetes mellitus in whom imaging was seminal in establishing the diagnosis of severe hemichorea-hemiballismus syndrome in the setting of nonketotic hyperglycemia.

Case Report

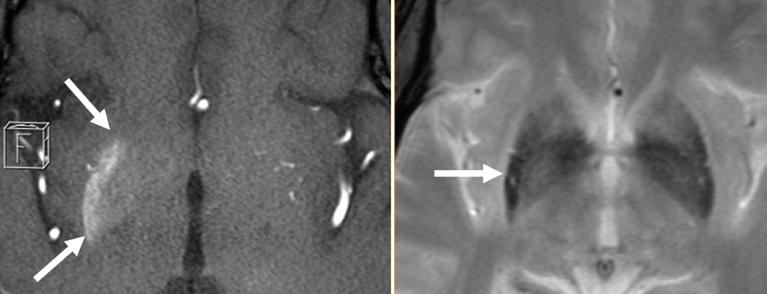

The 45-year-old patient was diagnosed with Guillain-Barré syndrome after several weeks of progressive tetraparesis and was treated with IVIG with very good results. However, choreatiform hyperkinesia of the left side of the body including the right side of the body became apparent during the course of the inpatient stay. of the face, which increased significantly and therapy-resistant in the subsequent rehabilitation treatment. The patient’s limited ability to cooperate was associated with a long history of poor diabetes control, as documented by an HbA1c of 18.5% at initial admission. An MRI of the skull performed after repositioning showed conspicuous basal ganglia changes contralateral to the side of the hyperkinesias (Fig. 1). This finding confirmed the suspected clinical diagnosis of hemichorea-hemiballismus syndrome in nonketotic hyperglycemia. Therapeutically, a consistent diabetological treatment was initiated. In the short term, the hyperkinesias could hardly be influenced by medication (neuroleptics, benzodiazepines, tiapridal and valproic acid).

Fig. 1: T1-w (axial source slices of TOF-MRA; left half of the image) shows a hyperintensity located in the right putamen and to a lesser extent in the right globus pallidum (extent marked with arrows). In the T2* sequence (right half of the image), the posterior portion of the right putamen (see arrow) is signal diminished in lateral comparison.

Discussion

Nonketotic hyperglycemia, which develops slowly over days to weeks, may be associated with various neurologic abnormalities. Most commonly, there are quantitative and qualitative disorders of consciousness, epileptic seizures, and focal neurologic deficits. Rarely, hemichorea hemiballismus syndrome may be caused, which is associated with hemiplegic hyperkinesias and characteristic radiologic features. The association of this movement disorder and nonketotic hyperglycemia was first described by Bedwell in 1960. This movement disorder may represent the initial manifestation of diabetes mellitus.

Women are affected more often than men. The median age of patients is approximately 70 years. Cases of the disease under the age of 40 are extremely rare. Clinically, it is the acute to subacute occurrence of choreatiform to ballistic movement disorders of one (or in 10% of cases both) half(s) of the body in poorly controlled type 2 diabetes, with significantly to massively elevated blood glucose and HbA1c levels at the time of onset of the movement disorder, the latter up to 19%. Facial involvement occurs in slightly less than one-third of patients.

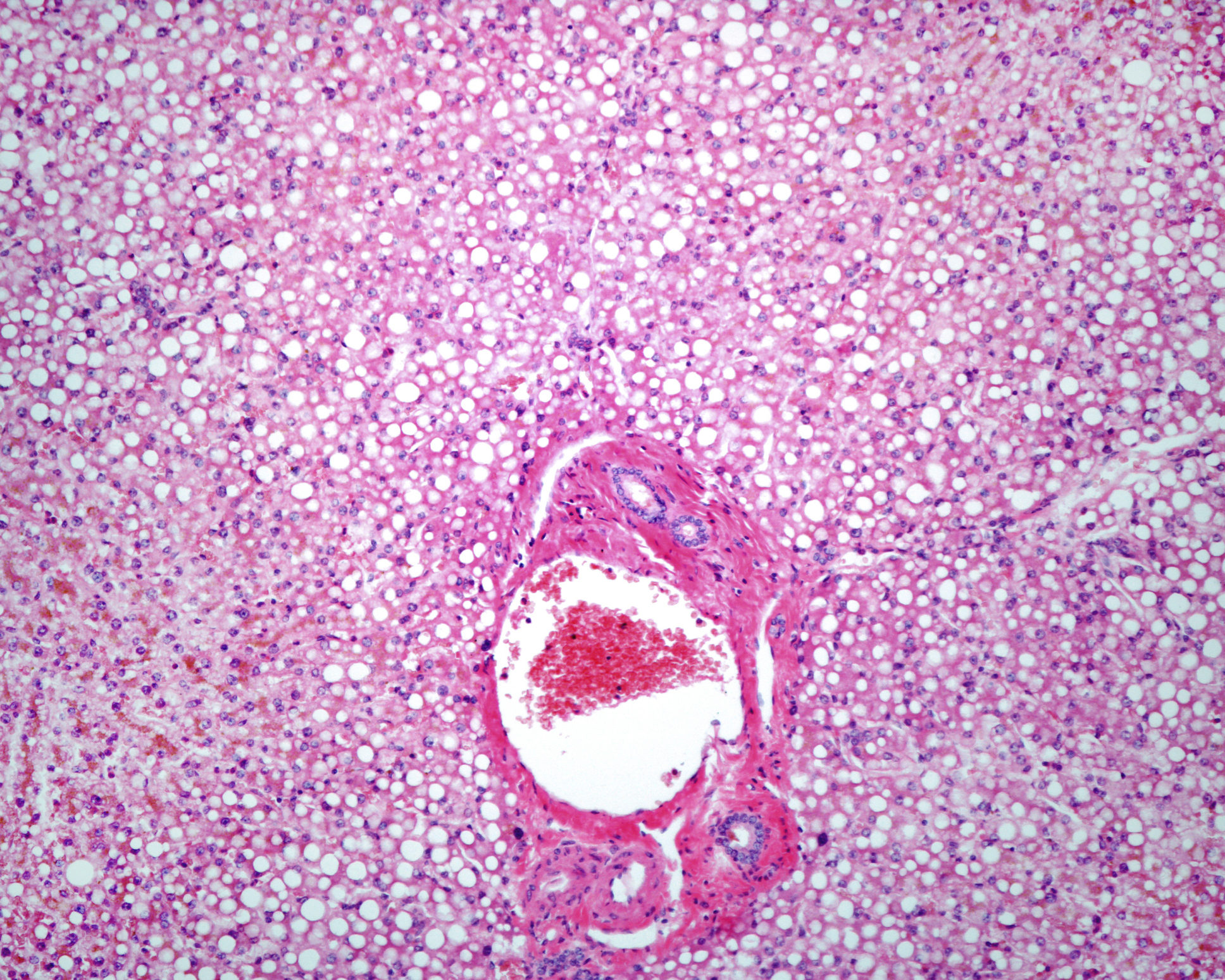

Imaging reveals non-KM-recording hyperdensities in the basal ganglia contralateral to clinical symptoms on CCT and hyperintensities in T1-weighted cMRI sequences. The findings in the T2-weighted images are more variable. Typical are hypointensities in the basal ganglia, which may also develop with a delay. In addition, iso- or hyperintensities may occur. While the putamen is always affected by the aforementioned changes, the inner capsule is almost regularly left out. DWI sequences may indicate diffusion restriction, and signal depression may occur in T2* recordings.

The cause of T1 shortening is controversial in the literature. In addition to calcifications in neurons, microbleeds and chronic ischemia with selective neuronal death and reactive gliosis are considered possible correlates. Petechial hemorrhage is blamed for T2* subsidence.

Therapeutically, the movement disorders may completely resolve within a few hours by lowering the elevated blood glucose; however, they may persist for several months. Within six months, almost all patients have recovered completely.

T1 hyperintensities in the basal ganglia usually regress within a few months. In a few patients, clinical symptoms persist despite regression of MRI lesions. Therapeutically, in addition to the indispensable lowering of blood glucose, the above-mentioned substances can be used medicinally.

It is important to recognize nonketotic hyperglycemia as a reversible cause of hemichorea-hemiballismus syndrome. In the presence of the triad of “hemichorea hemiballismus, hyperglycemia, and a T1 hyperintensity in the contralateral basal ganglia,” hyperglycemia-induced hemichorea hemiballismus syndrome should be considered as the cause.

Literature:

- Bedwell SF: Some observations on hemiballismus. Neurology 1960; 10: 619-622.

- Lin JJ, et al: Presentation of striatal hyperintensity on T1-weighted MRI in patients with hemiballism-hemichorea caused by non-ketotic hyperglycemia: report of seven new cases and a review of literature. J Neurol 2001; 248: 750-755.

- Seung-Hun O, Kyung-Yul L, Joo-Hyuk I, Myung-Sik L: Chorea associated with non-ketotic hyperglycemia and hyperintensity basal ganglia lesion on T1-weighted brain MRI study: a meta-analysis of 53 cases including four present cases. Journal of the Neurological Sciences 2002; 200: 57-62.

- Shalini B, Salmah W, Tharakan J: Diabetic non-ketotic hyperglycemia and the hemichorea-hemiballism syndrome: A report of four cases. Neurology Asia 2010; 15(1): 89-91.