More than half of all HIV patients suffer from sensory neuropathy, which is one of the most common HIV-associated diseases. There is no causal therapy for HIV-associated neuropathies; therefore, symptomatic therapy is analogous to non-HIV-associated neuropathies. In severe antiretroviral toxic neuropathy, switching antiretroviral medications may be necessary. Leading symptoms of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND) are psychomotor slowing, impaired concentration and memory, and impaired executive function. Early diagnosis is essential in the management of neurosyphilis, which is easily treated with penicillin. Diagnosis is usually difficult because a large number of patients present with nonspecific symptoms. Central nervous system involvement can occur at any stage of disease; the classic clinical pictures (progressive paralysis, tabes dorsalis) are rare in the era of antibiotics. Patients with HIV are at increased risk for neurosyphilis.

HIV disease and syphilis are infectious diseases that can manifest on the nervous system. Fortunately, according to the FOPH, there is a slight downward trend in the number of new HIV diagnoses. In contrast, there has been a resurgence in reported syphilis infections as well as other STDs in recent years. Both diseases influence each other: syphilis favors the transmission of HIV infection, and HIV-related immunodeficiency worsens the course of syphilis. To address this, awareness of the epidemiologic link between syphilis and HIV should be promoted among both medical staff and affected patient populations. The neurological manifestations of both diseases can be diverse and cause differential diagnostic difficulties in clinical practice. The aim of this review is to present the neurological involvement of HIV disease and syphilis, diagnostic measures and possible therapy in a way that is relevant to everyday life.

HIV and AIDS

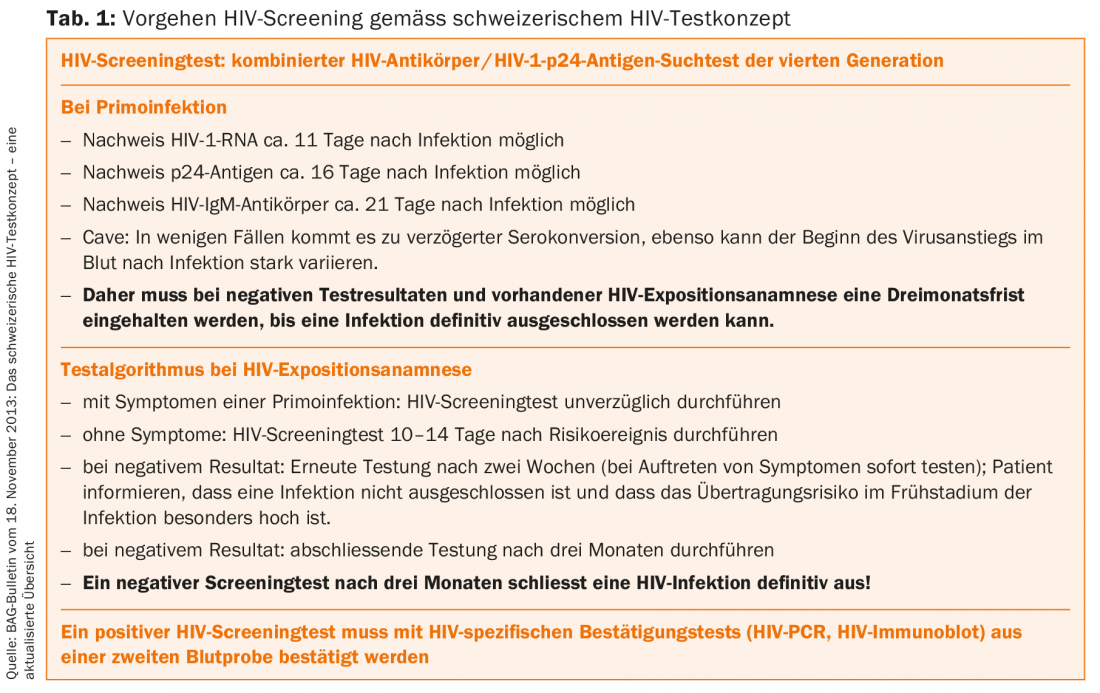

Humanimmunodeficiency virus(HIV) is a retrovirus that causes progressive weakening of the human immune system when infected. Worldwide, more than 35 million people are infected with HIV, including about 19,000 in Switzerland. Since 2009, new infections in Switzerland have slightly decreased, although HIV is still diagnosed in about 600 persons (approx. 25% women) each year (HIV screening, tab. 1) . Besides opportunistic infections and the induction of rare tumors, HIV infection mainly causes neuropathies and HIV-associated dementia. However, since the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) in 1996, neurological manifestations have declined, except for HIV-associated neuropathy [1,2].

Clinical manifestations – neuropathies

Peripheral nervous system disorders are among the most common HIV-associated diseases. More than half of all HIV patients show symptoms of sensory neuropathy, about one-third of which are painful. Distal symmetric polyneuropathy (HIV-DSP), which is probably directly HIV-associated, is distinguished from antiretroviral toxic neuropathy (HIV-ATN).

Pathophysiologically, a direct neurotoxic effect by HIV on the sensory ganglion cells and an indirect neurotoxic effect by altered lymphokine production by HIV-induced macrophages are discussed in HIV-DSP. HIV ATN is induced by dideoxynucleosides (stavudine, didanosine, and zalcitabine) and their mitochondrial toxic effect and possibly by protease inhibitors (indinavir, saquinavir, and ritonavir). Combinations of both neuropathies are common and should be differentiated from each other as much as possible because of different therapeutic consequences. Clinically, both present as distally symmetric neuropathies with stocking- and glove-like dys- and hypesthesias and/or burning pain. Motor involvement is rare. Electrophysiology reveals predominantly axonal polyneuropathy. The diagnostic and differential classification follows the general approach of polyneuropathies. Specific scores (Total Neuropathy Score, Brief Peripheral Neuropathy Screen) are suitable for clinical routine and follow-up documentation.

Since no causal therapy for HIV-DSP exists, symptomatic treatment is analogous to other neuropathies. In severe HIV-ATN, continuation or switching of antiretroviral medication should be discussed on an interdisciplinary basis, paying attention to the complex interactions of antiretroviral agents (www.hiv-druginteractions.org) [3].

HIV-associated mononeuritis multiplex and mononeuropathy are rare manifestations with sometimes rapidly progressive courses that occur in early stages of HIV disease. The cause is a secondary vasculitis induced by the HI virus, which can be bioptically detected with perivascular inflammatory infiltrates from CD8 cells. The therapy corresponds to the non-HIV-associated form, since no specific therapy concepts exist.

HIV-associated AIDP (“acute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy”) is rare and occurs in approximately 1% of patients, preferentially at the time of seroconversion. In addition to the clinic, a high CSF protein content with cytalbuminous dissociation is diagnostically groundbreaking; however, CSF pleocytosis of up to 150 cells/μl occurs in approximately 50% of HIV-infected patients. The clinical picture and its treatment correspond to the sporadic form.

Pathogen-associated neuropathies (incidence <1%) occur in advanced immunosuppression and present as polyneuroradiculitis with flaccid, rapidly progressive paraparesis and bladder voiding dysfunction. The pathogen can be detected in serum and cerebrospinal fluid, and cytomegalovirus can be detected in up to 80% of cases. CSF diagnostic findings include pleocytosis, elevation of total protein and immunoglobulins. It should be noted that further organ manifestations may occur as the disease progresses. Therapy depends on the pathogen [3,4].

Neurocognitive disorders due to HIV infection (HAND, “HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder”).

HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders have become less common with the introduction of HAART therapy, although they present a differential diagnostic challenge in the context of dementia assessment. HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder (HAND, “HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder”) has been introduced as a term that should be used in routine clinical practice [5].

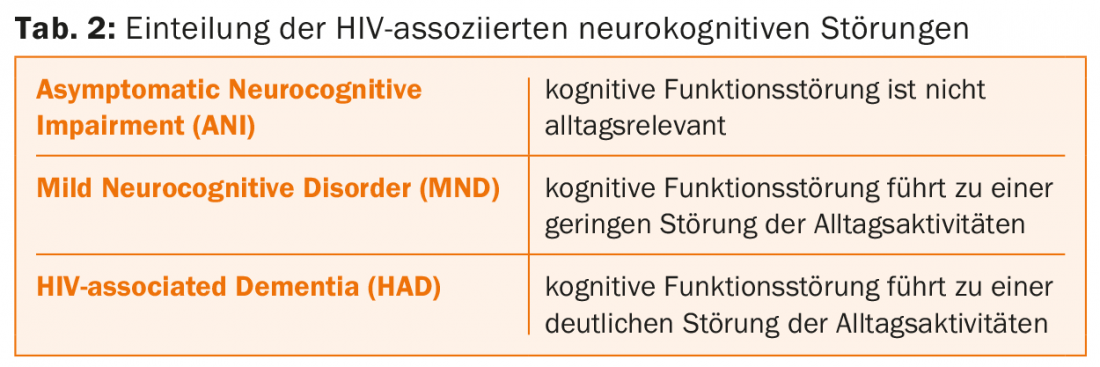

HAND is a subacute to chronic subcortical dementia, which in principle can occur at any stage of HIV infection. Neuropsychologically, psychomotor slowdowns, impaired concentration and memory, and executive dysfunction are evident. Psychotic symptoms are observed in approximately 15% in the final stage of HAND. Epileptic seizures occur in 5-10% of cases. Overall, three subtypes are distinguished according to the Frascati criteria (Tab. 2).

The etiology of HAND is not fully understood. It is possible that the cytopathogenicity of the HI virus involving transmembrane proteins leads to the destruction of neurons or the degeneration of synapses, although the virus itself is hardly present in neurons or glial cells. An increased viral load in the CSF can possibly promote the occurrence of HAND. In addition, a neurotoxic effect of HAART must also be considered.

Diagnostically groundbreaking is neuropsychological testing, for which the HIV Dementia Scale or the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) test are used. Symptomatic brain diseases (CNS lymphoma, toxoplasmosis, normal pressure hydrocephalus) must be excluded by MR tomography. HAND is associated with cortical and subcortical atrophy and white matter hyperintensities, with contrast enhancement inconsistent with the diagnosis. CSF diagnostics are used to differentiate opportunistic infections or neoplastic diseases. Neurosyphilis, CMV encephalitis, or Cryptococcus infections must be considered for differential diagnosis. In general, it is recommended to screen for neurocognitive impairment early after HIV infection and before HAART to have a baseline. The control interval should be between 6-24 months depending on the risk constellation. However, there is no prevention of HAND confirmed by studies. It is possible that early initiation of HAART may be beneficial [6].

Syphilis

“He who knows syphilis, knows medicine” is the famous quote from Sir William Osler. Known as the chameleon of medicine, syphilis is difficult to diagnose because of its many manifestations. Syphilis is a predominantly sexually transmitted, multi-stage chronic infectious disease caused by the gram-negative spiral-wound bacterium Treponema pallidum.

Epidemiology

Worldwide, the number of new syphilis cases is on the rise again, especially in wealthy countries including Switzerland. There is an increased risk of infection especially in men who have sex with men, in people with changing sexual partners and in the area of prostitution. In Switzerland, syphilis is subject to a non-nominal notification requirement. According to the Federal Office of Public Health, about 350 people are infected with syphilis in Switzerland each year; more than 80% of those infected are men.

Clinical manifestations

After an average incubation period of three weeks, a typical primary lesion (papule, ulcer) with indolent regional lymphadenopathy (primary syphilis) occurs at the site of pathogen entry. After 9-12 weeks, a systemic disease process, the secondary stage with typical skin changes and general symptoms, may develop. If untreated, the disease is chronic-recurrent for up to one year and then enters a latent phase lasting several years. If an inflammatory reaction against the pathogens develops in the late phase, the symptoms of tertiary syphilis characterized by granulomatous reactions may occur.

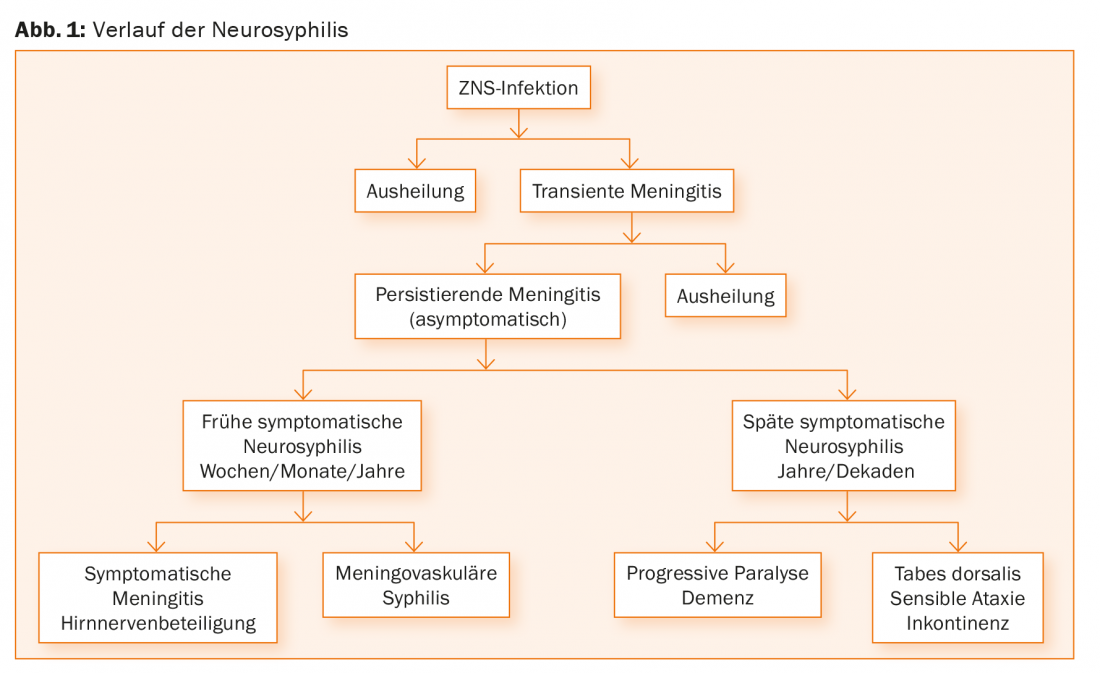

Neurosyphilis is defined as an infection of the central nervous system during any stage of the disease. Early on, there is predominantly colonization of the cerebrospinal fluid, meninges, and neuronal vessels. Already in the secondary stage, a (mostly asymptomatic) CSF pleocytosis is present in up to 40% of patients [7]. In the late stage, the brain or spinal cord tissue is directly attacked. Since in the natural course of syphilis only about 5-10% of the diseased develop neurosyphilis, self-healing in the CNS is obviously possible. Either spontaneous healing occurs after CNS infection or transient meningitis occurs, which can develop into manifest symptomatic neurosyphilis if the pathogen is not eliminated, especially in HIV patients (Fig. 1) [8].

Early forms of progression

Early syphilitic meningoencephalitis manifests with a latency of six weeks to 12 years in one-third of all infected individuals. Frequently, this is asymptomatic and characterized only by an inflammatory CSF syndrome [9]. Clinically, a meningitic clinical picture initially appears with headache, neck pain, and nausea, accompanied by sleep disturbances, irritability, and affect lability. In addition, cranial nerve loss of the occulomotor, facial, and vestibulocochlear nerves or epileptic seizures may occur.

Meningovascular syphilis occurs with a latency of 4-12 years and is markedly variable in its expression and manifestation. The meningitic course manifests as headache, cranial nerve lesions, optic nerve damage, and rarely hydrocephalus. The vasculitic variant is due to obliterative endarteritis affecting the medium-sized vessels at the base of the brain (so-called Heubner’s arteritis). It is characterized by fibroblast proliferation of the intima, thinning of the media, and fibrous and inflammatory changes of the adventitia. Clinically, stroke symptoms such as mono- and hemiparesis, visual field loss, brainstem syndromes, dizziness, hearing loss, but also spinal symptoms, epileptic seizures, and a brain-organic psychosyndrome are prominent.

Late forms of progression

The classic clinical syndromes of tertiary-stage neurosyphilis are very rare, even among other indications, because of the wide availability and use of antibiotics. They are characterized by parenchymatous damage with diffuse, progressive, and irreversible neuronal damage. Progressive paralysis (latency 15-20 years) represents chronic encephalitis with a very slow progressive course. Initially, headaches and dizziness are prominent, as well as cognitive deficits, weakness in criticism and judgment, psychotic episodes, and speech disorders. In the course, an organic psychosyndrome with epileptic seizures, reflex abnormalities and tongue tremor occurs. Finally, severe dementia with urinary and fecal incontinence and marasmus is prominent. Some patients present with manic or paranoid episodes, such as the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche and the composer Robert Schumann. Without appropriate therapy, this ends lethally after three to five years.

Tabes dorsalis (latency 15-20 years) corresponds to chronic progressive posterior cord degeneration in dorsal ganglionitis. The pathognomonic clinical picture consists of areflexia of the lower extremities, pupillary dysfunction (reflex pupillary rigidity = Argyll-Robertson sign), gait ataxia, and micturition disturbances. Typically, patients complain of shooting-in (“lancing”) pain.

Syphilitic tumors are circumscribed space-occupying granulomas, which mostly originate from the meninges at the brain convexity. Symptomatology depends on the location, but may remain asymptomatic for longer periods. Polytopic occurrence is referred to as gummy neurosyphilis.

Diagnostics

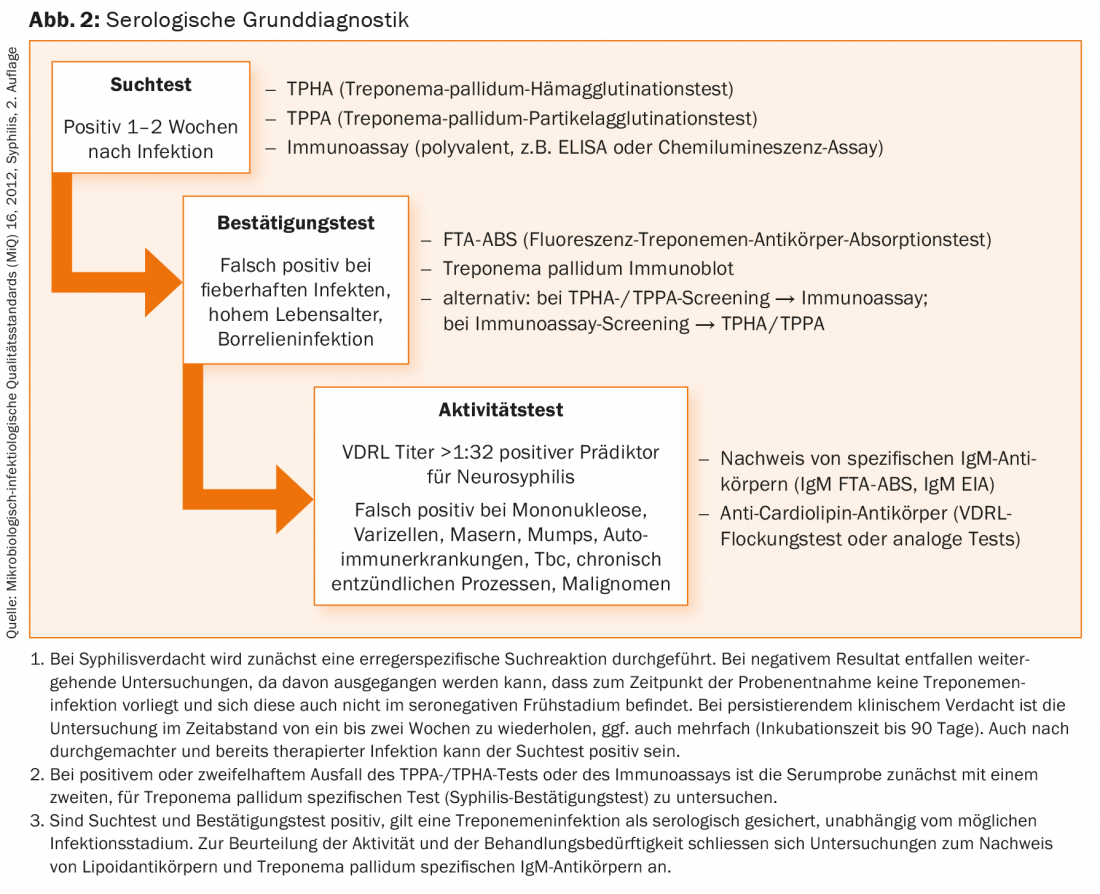

Clinical suspicion, serologic testing, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) diagnosis are key. The serodiagnosis of syphilis is performed as a step-by-step diagnosis (Fig. 2). If syphilis is present, other sexually transmitted infections (STI) can be diagnosed (HIV, hepatitis B and C infections, genital swabs for chlamydia and gonococci).

Diagnosis of neurosyphilis

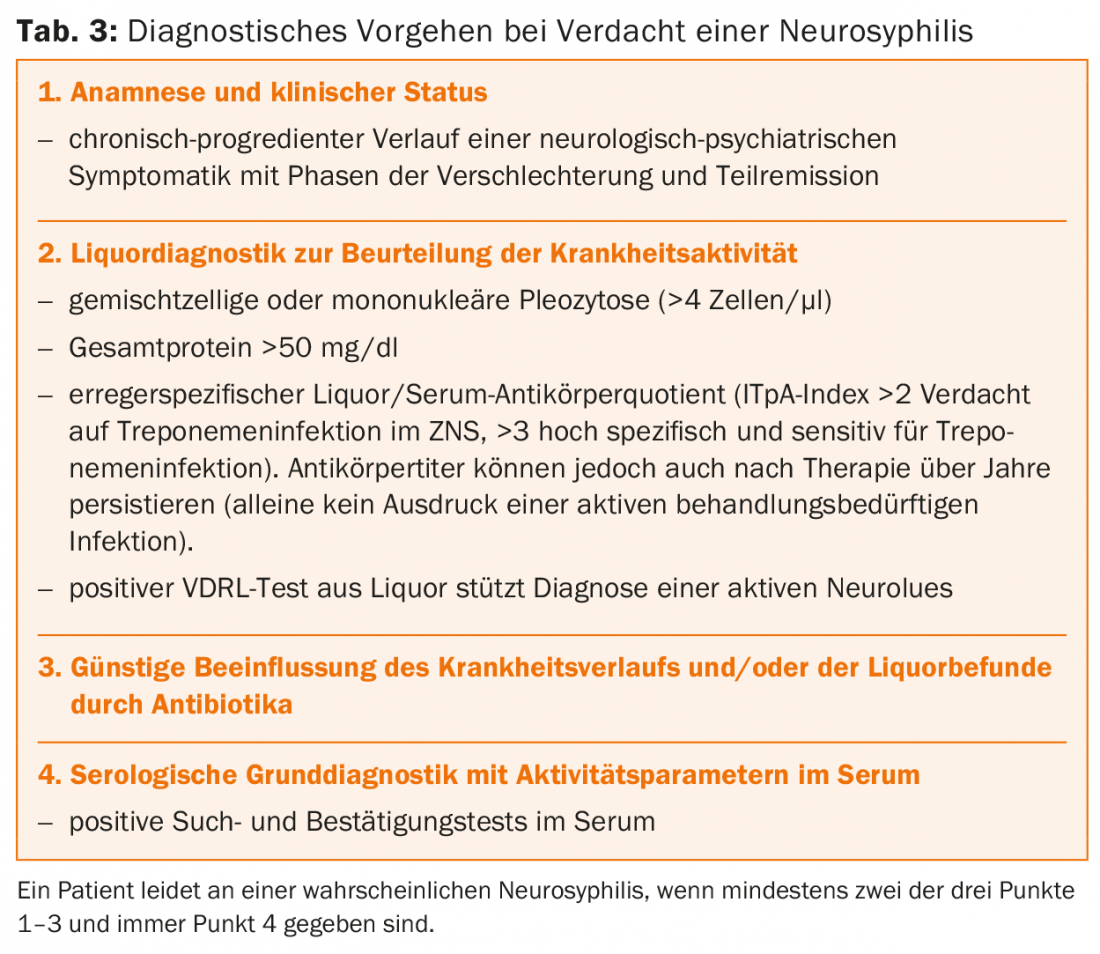

The diagnosis of neurosyphilis is based on clinical findings, serologic test results, and CSF diagnosis. However, the definition of neurosyphilis is still controversial today. According to the DGN guidelines (www.dgn.org), diagnosis in suspected cases of neurosyphilis is recommended as shown in Table 3 .

Imaging

Imaging in neurosyphilis is normal, especially in subclinical courses. In syphilitic meningitis, there may be contrast enhancement of the meninges, cranial nerves, or spinal nerves, with cortical and subcortical infarcts added in meningovascular syphilis. Brain atrophy or small-spot demyelination foci can be seen not only in progressive paralysis but in all forms of neurosyphilis [10].

Syphilis in HIV coinfection

HIV-positive patients also undergo the typical stages of syphilis. However, atypical and more severe courses with rapid progression and more frequent neurosyphilis occur. HIV-infected individuals are usually younger and often develop syphilitic meningitis. Fulminant necrotizing neurosyphilis is also more common [11]. This correlates with the extent of immunodeficiency. Neurosyphilis in HIV-infected individuals with less than 350 helper cells/μl is three times more common than in uninfected individuals [8]. In addition, previously experienced syphilis can be reactivated in HIV patients.

Therapy

The first-line therapy for symptomatic and asymptomatic neurosyphilis is i.v. administration of penicillin G. This achieves therapeutic levels even in the cerebrospinal fluid. Required to maintain a continuous level of activity for at least 10-14 days in early syphilis and for two to three weeks in late syphilis with a daily dose of 18-24 million IU/d. The long-term depot preparation benzathine benzylpenicillin is not suitable for the therapy of neurosyphilis.

Alternatively, if syphilitic CNS involvement is suspected or confirmed, daily single i.v. administration of 2 g/d ceftriaxone (initial dose 4 g) may be given for 14 days. Second-line therapy is oral doxycycline (2× 200 mg/d for 28 days).

Literature:

- Schütz SG, Robinson-Papp J: HIV-related neuropathy: current perspectives. HIV AIDS (Auckl) 2013; 5: 243-251.

- Tarr P, et al: HIV infection: 2015 update for family physicians. SMF 2015; 15: 479-485.

- Hahn K, Husstedt IW: HIV-associated neuropathies. Neurologist 2010; 81(4): 409-417.

- Amruth G, et al: HIV Associated Sensory Neuropathy. J Clin Diagn Res 2014; 8(7): MC04-7.

- Antinori A, et al: Updated research nosology for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. Neurology 2007; 69(18): 1789-1799.

- Eggers C: HIV-1-associated neurocognitive disorder: current epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and therapy. Neurologist 2014; 85(10): 1280-1290.

- Fildes P, Parnell RIG, Maitland HB: The occurrence of unsuspected involvement of the central nervous system in unselected cases of syphilis. Brain Oxford University Press 1918; 41(3-4): 255-301.

- Marra CM, et al: Cerebrospinal fluid abnormalities in patients with syphilis: association with clinical and laboratory features. J Infect Dis 2004 Jan 31; 189(3): 369-376.

- Ali L, Roos KL: Antibacterial therapy of neurosyphilis: lack of impact of new therapies. CNS Drugs 2001 Dec 31; 16(12): 799-802.

- Brightbill TC, et al: Neurosyphilis in HIV-positive and HIV-negative patients: neuroimaging findings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1995 Mar 31; 16(4): 703-711.

- Katz DA, Berger JR, Duncan RC: Neurosyphilis. A comparative study of the effects of infection with human immunodeficiency virus. Arch Neurol 1993 Feb 28; 50(3): 243-249.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2015; 13(4): 8-14.