Surgical treatment of patients with hereditary connective tissue disease aims to prevent aortic dissection. This is because it is responsible for the high mortality rate of the patient population. When is the indication given? And what are the drug therapy options?

Hereditary connective tissue diseases with vascular manifestations are rarely present in the consciousness of the general medical clinician. For a long time, Marfan syndrome was the only differential diagnosis in this direction in young patients with a thoracic aortic event. Within the last decade, hundreds of genes associated with syndromal and nonsyndromal forms of aortic disease have been identified [1].

Further, however, nearly half of patients are diagnosed only in the setting of a vascular complication. While aneurysms are mostly detected during a routine examination, aortic dissection is one of the surgical emergencies associated with high morbidity and mortality.

Marfan syndrome is an autosomal dominant inherited disorder with an incidence of approximately 1:5000 live births. The typical ocular, skeletal, and cardiac manifestations are caused by mutations in the fibrillin-1 gene that lead to overactivation of the TGFβ pathway [2].

Bart Loeys and Hal Dietz identified a subpopulation of patients ten years ago who were notable for a split uvula, wide interocular distance, and tortuous vessels. In the meantime, various genes have also been identified that lead to a phenotype from the Loeys-Dietz syndrome group. Identifying these patients is important because dissections often occur at aortic diameters that were not previously considered indications for prophylactic aortic replacement [3].

The rare vascular Ehlers-Danlos syndrome is caused by mutations in the gene encoding collagen III. These patients are notable for their high rate of dissection and rupture without prior aneurysm formation. This makes the care of these patients very difficult. Median survival is 48 years if untreated, with the first events usually occurring in the third to fourth decade of life [4].

Surgical treatment options

The goal of surgical treatment of patients with hereditary connective tissue disease is to prevent aortic dissection due to dilatation of the aorta, as this is responsible for the high mortality in this patient population. The 2014 European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guidelines make a clear distinction in the indication for elective aortic replacement between Marfan or Loeys-Dietz patients and patients without underlying genetic disease [5]. The difficulty here lies in the demarcation. In young patients, the presence of a genetic component must be assumed. In patients without connective tissue disease, prophylactic aortic replacement is recommended when the diameter of the aortic root or ascending aorta is 55 mm. Marfan patients, on the other hand, should be operated on at 50 mm, and even at 45 mm if risk factors are present (such as family history of dissection). In Loeys-Dietz patients, elective replacement is advised at 42-45 mm. As a rule, the primary procedure is replacement of the aortic root. If possible, an attempt is made to preserve the patient’s own valve. If this is not feasible due to damage to the valve, a valve-bearing conduit is implanted.

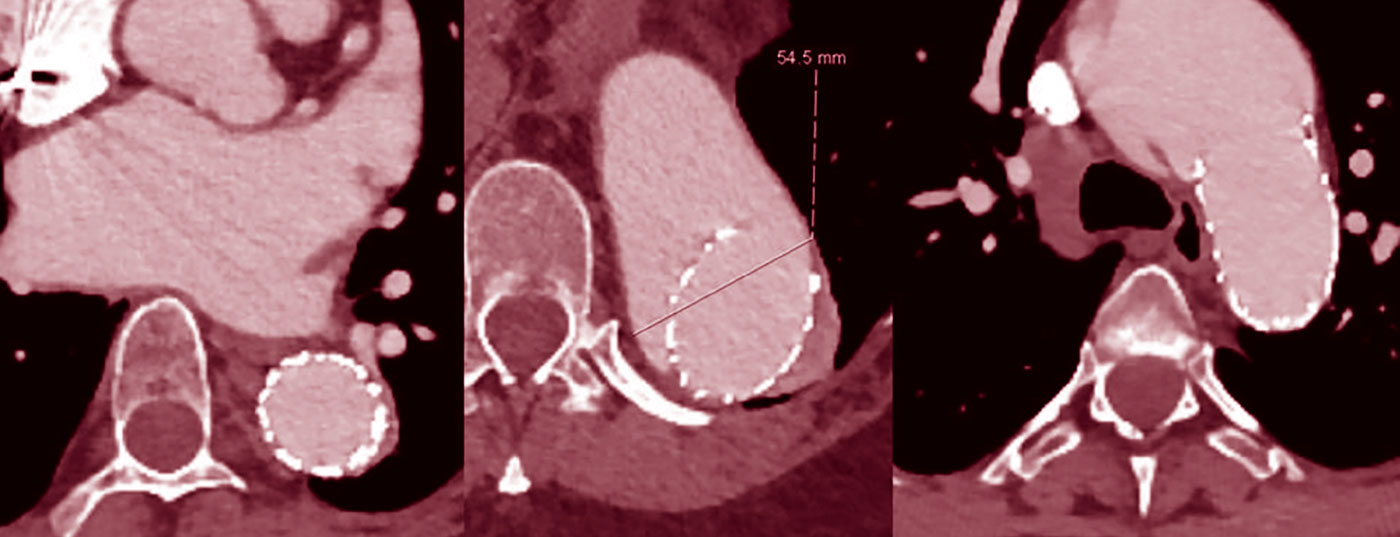

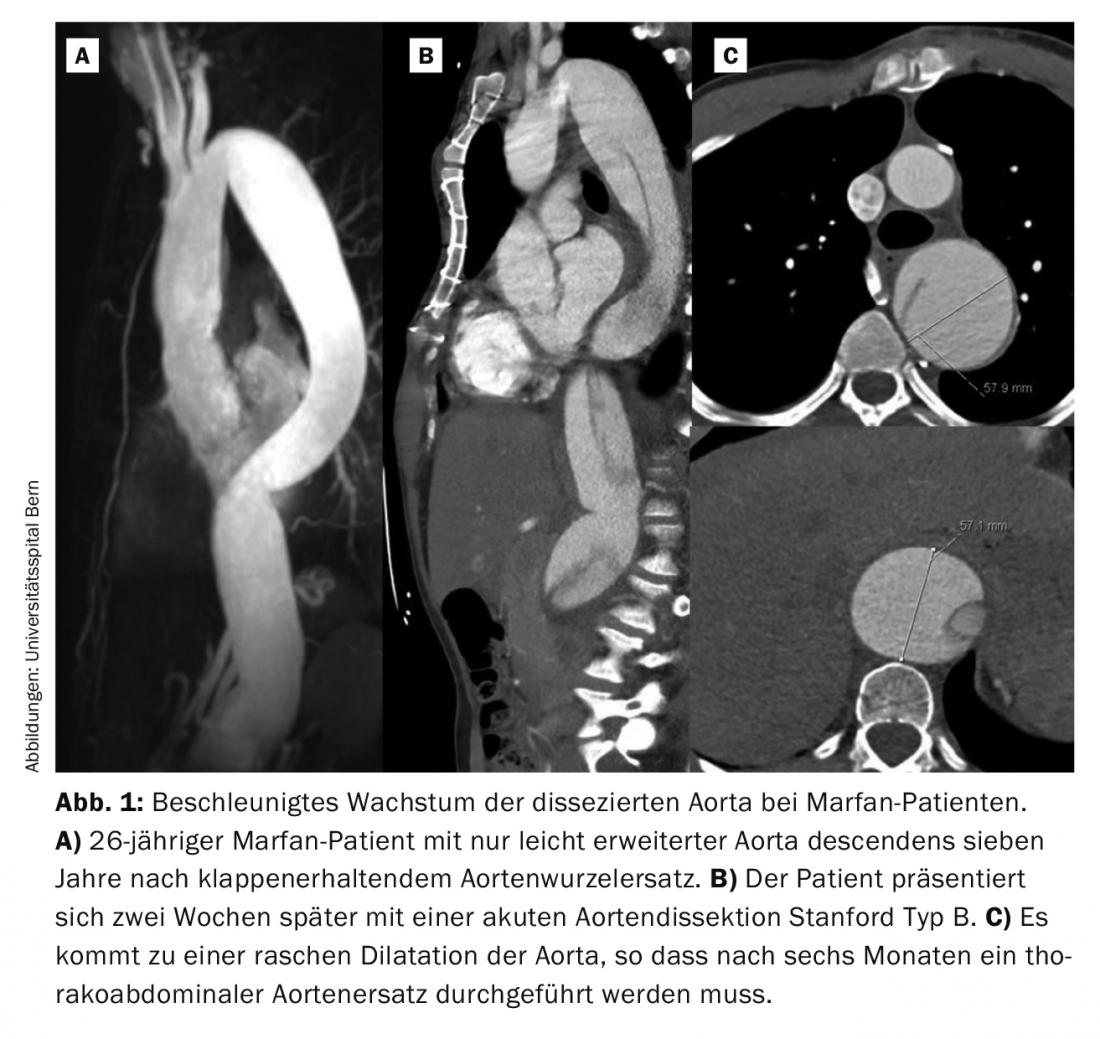

However, often the initial manifestation is acute aortic dissection Stanford type A or B. In our experience over the last twenty years, one third of patients presented with acute dissection. Acute type A dissection is a surgical emergency and must be treated immediately. Even with successful surgery, half of these patients require re-operation, mostly on the distal, i.e. non-replaced, aorta. In patients with elective replacement of the aortic root, only about 10% of patients require reoperation. In most cases, these are patients who have suffered a type B aortic dissection in the interim. Although type B aortic dissection is often initially “uncomplicated,” i.e., without malperfusion, the aorta must subsequently be replaced thoracoabdominally in the vast majority of Marfan patients. Typical in Marfan patients is a rapid growth of the dissected aorta within the first weeks and few months (Fig. 1) . Experience shows that 50% of patients require surgery in the first year after the event [6].

Treatment of dilated thoracoabdominal aortic segments with stent grafts is generally not recommended because the landing zone vascular segments often undergo secondary dilatation (Fig. 2), even if there is good initial remodeling [7].

Drug options

Dilatation and the resulting risk of dissection of the aorta is the major cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with hereditary connective tissue disease. The goal of drug treatment is to reduce the progression of dilatation and the incidence of dissection. In this context, the reduction of blood pressure to maximum systolic values of 120 mmHg and the rate of pressure increase in the aortic region with each heartbeat are of relevant importance. Traditionally, the beta-blocker is the drug of choice [8]. Studies have shown a lower rate of dilatation in patients on beta-blocker therapy, but without clinical significance in terms of survival [9].

In recent years, the ATII receptor blocker losartan has been studied in more detail. Since it directly interferes with the TGFβ signaling pathway, high hopes are pinned on its effect in terms of prevention of aortic dilatation and dissection [10]. However, a large randomized trial in children with Marfan syndrome found no difference between beta-blockers and losartan [11]. The study was controversial because it ultimately compared a very high dose of atenolol with a relatively low dose of losartan. Due to its lower side effect profile, the ATII antagonist is therefore our first choice for the treatment of therapy-naïve patients with normal pump function. ATII antagonists are well tolerated, especially by children and adolescents. Smaller studies have shown that blood pressure is not significantly reduced in this patient population [12].

Progress controls

To detect the occurrence or progression of an aortic aneurysm in time and to avoid aortic dissection by early prophylactic aortic replacement, it is essential to perform close follow-up [13]. Here, it is important to systematically evaluate all aortic segments. Furthermore, controls after aortic surgery are important to detect possible complications such as aneurysm formation in other aortic segments and asymptomatic dissections at an early stage.

In our consultation, patients are checked postoperatively at three and twelve months by angio-CT and later, depending on the findings, once or three times a year. To reduce the cumulative radiation dose, this should be done predominantly by MRI. MRI examination also offers the advantage of functional imaging with regard to pump function, valvular vitiation, and ischemia diagnosis. Previous surgeries with implants are rarely a problem when evaluating the images. Currently, CT angiography is still superior to MRI in the evaluation of dissections. Echocardiographic controls are used in cases of vitia or st.n. Valve replacement performed once a year or alternately with MRI examination.

A special situation in the long-term care of patients with hereditary connective tissue diseases is the desire to have children. There is little evidence in this area, and recommendations from professional societies are sometimes contradictory [5,14,15]. In general, an aortic diameter <40 mm is considered to pose a reasonable risk of becoming pregnant under close echocardiographic monitoring and beta blockade. For diameters >45 mm, prophylactic surgery is clearly advised. For diameters between 40 and 45 mm, the individual situation of the patient must be weighed very carefully. Risk factor here is certainly a positive family history with regard to dissections, especially during pregnancy.

Current guidelines recommend screening of all first-degree relatives in a patient with a thoracic aortic aneurysm. This step can make a significant contribution to reducing the rate of patients with dissections.

Take-Home Messages

- In patients with hereditary connective tissue diseases, the indication for prophylactic aortic replacement is already given at diameters of 45-50 mm.

- Regular, systematic evaluation of all aortic segments prevents dissections and ruptures.

- All 1st-degree relatives of patients with thoracic aortic aneurysm should be screened for the presence of one.

Literature:

- Brownstein AJ, et al: Genes associated with thoracic aortic aneurysm and dissection: 2018 update and clinical implications. Aorta (Stamford) 2018; 6: 13-20.

- Habashi JP, et al: Losartan, an AT1 antagonist, prevents aortic aneurysm in a mouse model of Marfan syndrome. Science 2006; 312: 117-121.

- Loeys BL, et al: Aneurysm syndromes caused by mutations in the TGF-beta receptor. N Engl J Med 2006; 355: 788-798.

- Pepin M, et al: Clinical and genetic features of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV, the vascular type. N Engl J Med 2000; 342: 673-680.

- Erbel R, et al.: 2014 ESC Guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of aortic diseases: Document covering acute and chronic aortic diseases of the thoracic and abdominal aorta of the adult. The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Aortic Diseases of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2014; 35: 2873-2926.

- Schoenhoff FS, et al: Acute aortic dissection determines the fate of initially untreated aortic segments in Marfan syndrome. Circulation 2013; 127: 1569-1575.

- Grabenwöger M, et al: Thoracic Endovascular Aortic Repair (TEVAR) for the treatment of aortic diseases: a position statement from the European Association for Cardio- Thoracic Surgery (EACTS) and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC), in collaboration with the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI). Eur Heart J 2012; 33: 1558-1563.

- Shores J, et al: Progression of aortic dilatation and the benefit of long-term beta-adrenergic blockade in Marfan’s syndrome. N Engl J Med 1994; 330: 1335-1341.

- Gersony DR, et al: The effect of beta-blocker therapy on clinical outcome in patients with Marfan’s syndrome: a meta-analysis. Int J Cardiol 2007; 114: 303-308.

- Habashi JP, et al: Angiotensin II type 2 receptor signaling attenuates aortic aneurysm in mice through ERK antagonism. Science 2011; 332: 361-365.

- Lacro RV, et al: Atenolol versus losartan in children and young adults with Marfan’s syndrome. N Engl J Med 2014; 371: 2061-2071.

- Brooke BS, et al: Angiotensin II blockade and aortic-root dilation in Marfan’s syndrome. N Engl J Med 2008; 358: 2787-2795.

- Jondeau G, et al: Aortic event rate in the marfan population a cohort study. Circulation 2012; 125: 226-232.

- Baumgartner H, et al: ESC Guidelines for the management of grown-up congenital heart disease (new version 2010). Eur Heart J 2010; 31: 2915-2957.

- Hiratzka LF, et al.: 2010 ACCF/AHA/AATS/ACR/ASA/SCA/SCAI/SIR/STS/SVM guidelines for the diagnosis and management of patients with Thoracic Aortic Disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, American College of Radiology, American Stroke Association, Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Interventional Radiology, Society of Thoracic Surgeons, and Society for Vascular Medicine. Circulation 2010; 121: e266-369.

CARDIOVASC 2018; 17(5): 27-29