The median hourly wage of self-employed physicians in medical practice is 90 francs, and the annual income is 162,455 francs net. This is the conclusion reached by the Swiss Federal Statistical Office (SFSO) in a recently published analysis. In particular, the work of affiliated physicians and an own practice pharmacy increase the income relevantly. And gender – not unexpectedly – also plays a role.

For the fourth time, the Swiss Federal Statistical Office (SFSO) conducted the survey on structural data for medical practices and outpatient centers MAS in 2019. Published the results in November 2021 in various brochures. One of these is devoted for the first time separately to the income of self-employed physicians in private practice in Switzerland. It is based on data from 6472 self-employed physicians who own a sole proprietorship [1].

An average of just over 200,000 Swiss francs per year

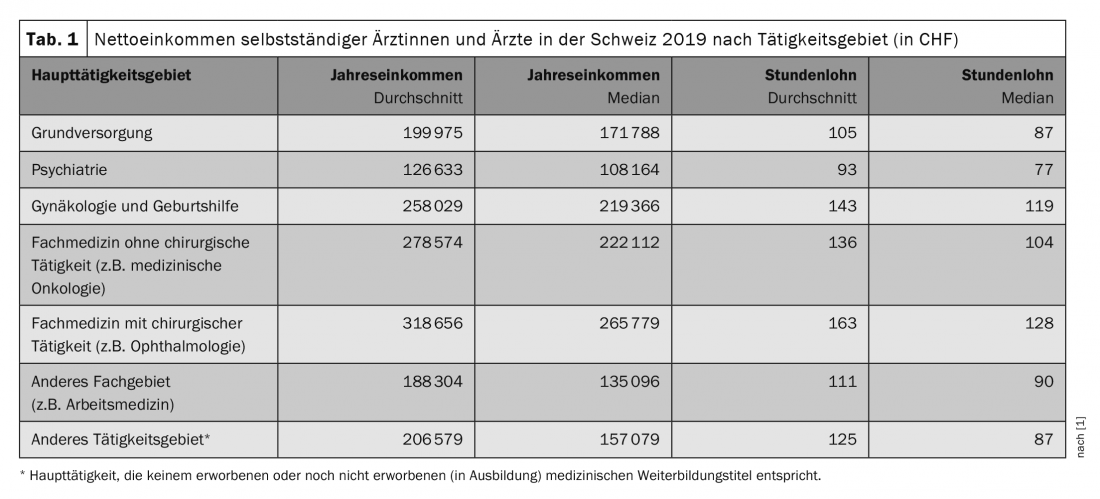

In 2019, the average annual income was 204,985 Swiss francs, according to the analysis, which corresponded to an average hourly wage of CHF 115. The median income was 162,455 francs per year. While wages were lowest in psychiatry with an average hourly wage of CHF 93, they were highest in those specialties with surgical activities (Table 1) [1].

In addition to the hours worked and the main area of activity, other influencing factors were identified. For example, working as an attending physician, which is particularly common in the surgical fields and in obstetrics, and having one’s own practice pharmacy had a positive effect on income. However, this is only permitted in some German-speaking cantons of Switzerland. Medication dispensing by the practice was associated with an increase in earnings of about 18%, and an attending practice was associated with an increase in earnings of about 11% [1].

On the other hand, being part of a group practice was associated with a lower income. And a large proportion of treatments subject to the KVG also hit the wallet. Far more profitable are those benefits that are covered by supplementary or accident insurance, for example. It is therefore not surprising that the average hourly wage of those physicians in whose practice less than 60% of patients were treated under the compulsory health insurance scheme was particularly high at CHF 132. However, KVG patient encounters accounted for at least 90% of cases in most practices. On average, the income generated from KVG services was 88% of total income [1].

Significant gender gap

As in other industries, the gender gap cannot be overlooked in the analysis of salaries for self-employed physicians. All other things being equal, physicians earned an average of 25% more than their female counterparts in 2019. While the median annual income for men was CHF 192,515, it was CHF 124,906 for women. The higher employment rate among men only partially explains this striking difference, which can be expressed in the average hourly wage. This amounted to CHF 122 for male physicians and CHF 103 for female physicians. Both annual earnings and hourly wages were higher for men than for women in all age groups. Incidentally, their share is significantly higher among younger physicians. For example, in 2019, women accounted for 58% of physicians under the age of 45, compared with only 35% of those aged 55 to 64 [1].

In contrast to gender, the country of origin of the medical degree does not seem to have any influence on the income of self-employed male and female physicians in Switzerland. And even an urban or rural location of the activity is unlikely to have any influence – unlike the canton in which the practice is located. Schwyz is the best performer, with the canton of Neuchâtel bringing up the rear [1].

Source: Media release “Transparency about the outpatient income of the medical profession”, 5.11.2021, FMH, Bern.

Literature:

- Income of self-employed physicians in medical practices in 2019 – Statistics of medical practices and ambulatory centers (MAS). Federal Statistical Office (FSO). Neuchâtel, 2021. www.statistik.ch

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2022; 10(1): 46-48.

InFo PAIN & GERIATry 2022; 4(1-2): 19