Blistering autoimmune dermatoses of the skin are among the rare diseases and are often fatal if left untreated. Intensive therapy can significantly improve the prognosis and quality of life of those affected. As a recently published analysis of patient data shows, achieving disease control is an achievable treatment goal, although this requires individualized strategies and may involve multiple therapy changes. To counteract the dysfunctional immune response against endogenous structural proteins, various drug intervention options are available today.

What is true for many other dermatological diseases is especially true for the autoimmune dermatosis pemphigus vulgaris: to select and implement the individually best fitting therapy from the multitude of treatment options is the key to success. Prof. Dr. med. Margitta Worm from the Charité University Medical Center Berlin, gave an up-to-date overview of pemphigus disease at the FOMF Allergology and Dermatology Hofheim (D) and presented the most important points of the 2019 revised guidelines for diagnosis and therapy of bullous pemphigoid and pemphigus vulgaris/foliaceus by the German Society for Dermatology [1,2]. Both are rare diseases with a high “burden of disease.”

Autoantibody detection as diagnostic gold standard

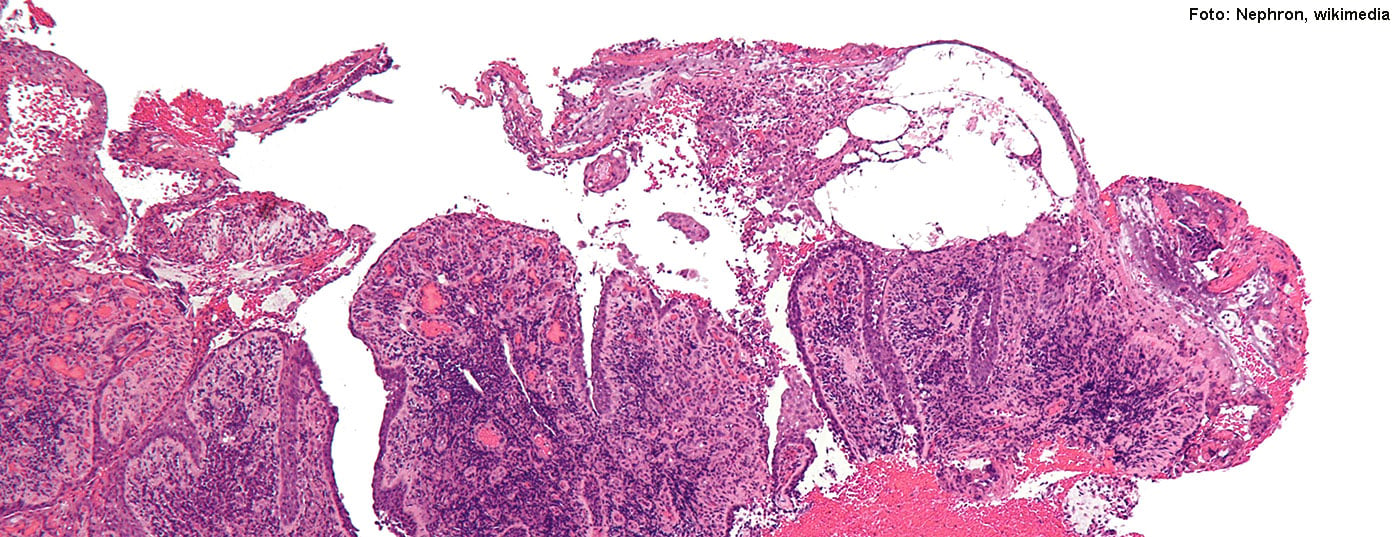

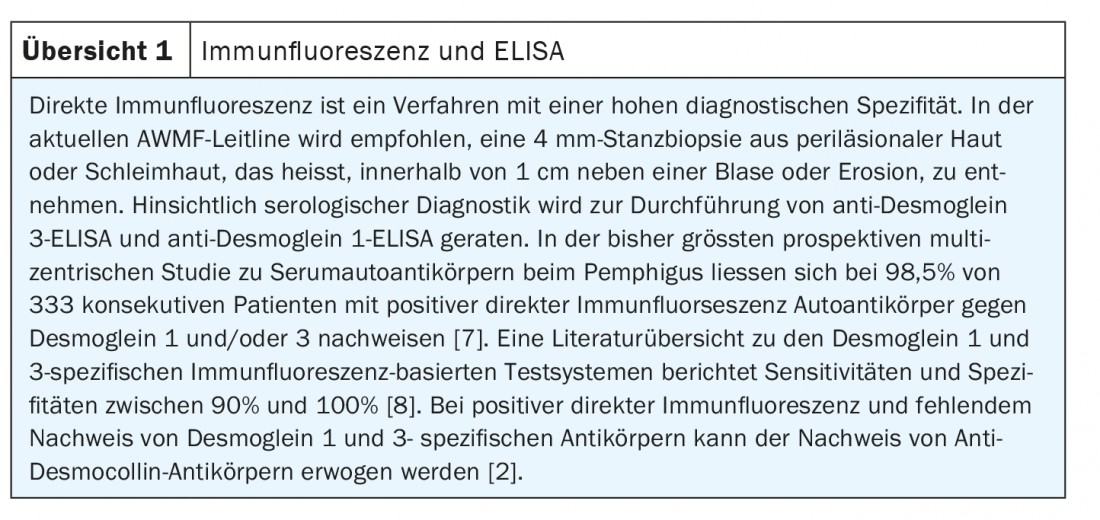

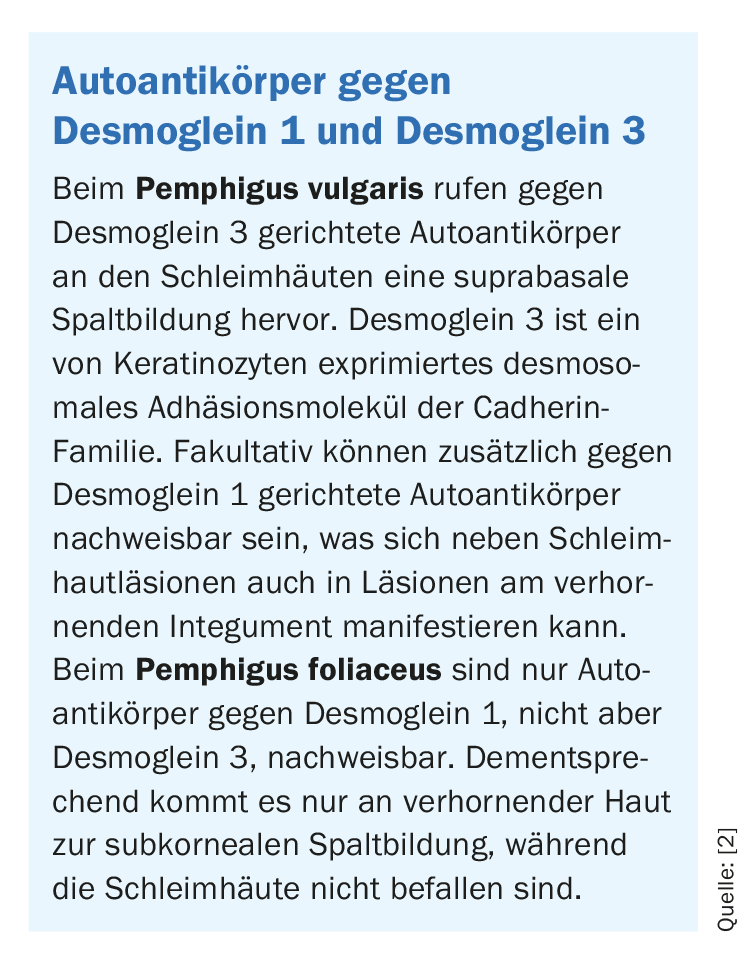

Pemphigus vulgaris, along with bullous pemphigoid, is the most important representative of blistering autoimmune dermatoses (Fig. 1A, C) . Approximately 80% of pemphigus cases are pemphigus vulgaris, most commonly occurring between the 4th and 6th decades of life; the second most common variant is pemphigus foliaceus, and other forms are very rare [2]. The diagnosis is made by a combination of different methods. In cases of clinical suspicion, in addition to histopathological examinations (Fig. 1B) , an in vivo test of autoreactive immunoglobulins by direct immunofluorescence and the detection of pathological autoantibodies by serological diagnostics are recommended. According to the guideline, anti-desmoglein 3-ELISA and anti-desmoglein 1-ELISA are most suitable for this purpose (overview 1). Pathological autoantibodies play an important role in the pathomechanism of pemphigus diseases. While in pemphigus vulgaris autoantibodies directed against desmoglein 3 cause a suprabasal cleft in the mucous membranes, in pemphigus foliaceus only autoantibodies against desmoglein 1 are detectable, which is clinically manifested in the fact that only the keratinizing skin, but not the mucous membranes are affected.(Box). If left untreated, pemphigus can be fatal, usually due to infections originating from the open skin lesions. Intensive therapy can reduce the dangerousness of the disease and significantly improve the quality of life. For this purpose, regular check-ups with the dermatologist are required [3].

Glucocorticoids and nonsteroidal immunomodulators are mainstays of first-line therapy

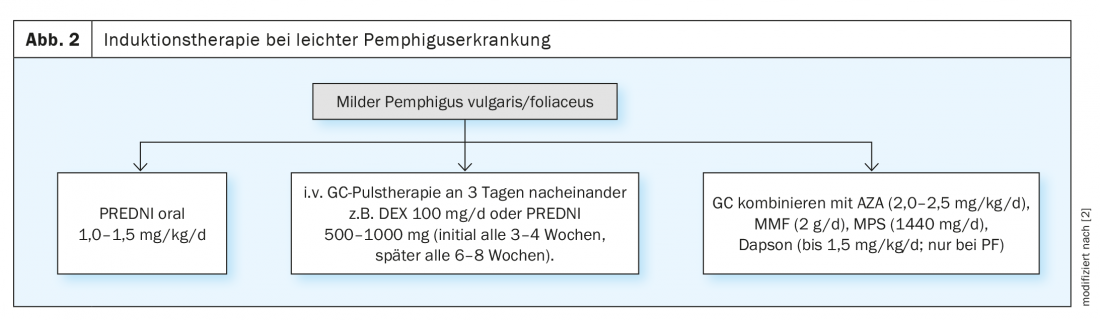

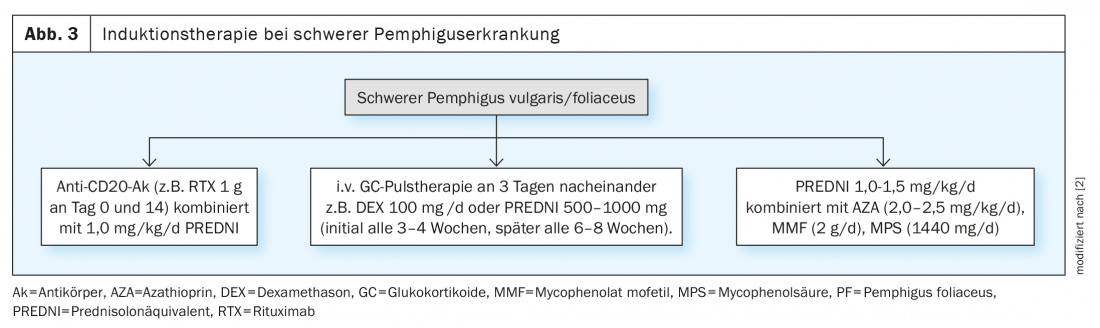

The treatment of pemphigus disease is based on the severity and pattern of the disease as well as therapy-relevant comorbidities. A compact overview is shown in Figures 2 and 3. In order to dampen the excess immune response of the patient’s own body, long-term immunosuppression with systemically administered drugs is required in most affected individuals. The therapeutic goal of induction therapy is to control disease activity, which is considered achieved when no new lesions appear and incipient healing of existing lesions is observed [2]. The guideline recommends combining corticosteroids with a nonsteroidal immunosuppressive agent such as azathioprine or mycophenolate mofetil. Instead of cortisone tablets, glucocorticosteroids can alternatively be administered as an infusion [2,4]. In “dexamethasone pulse therapy”, dexamethasone is infused into the vein on three consecutive days, which is initially repeated every three to four weeks and later at larger intervals. To prevent side effects of cortisone therapy, such as gastrointestinal ulcers, proton pump inhibitors are usually used. Calcium and vitamin D3 supplementation may be considered for osteoporosis prevention, as well as biennial bone densitometry at most. In parallel with systemic therapy, external treatment measures are also important, such as mouth rinses, ointments and antiseptic compresses or poultices.

Rituximab soon available as second-line therapy in Switzerland?

If the therapeutic goal is not achieved by the use of glucocorticoids in combination with immunomodulators/immunosuppressants, high-dose intravenous immunoglobulins or the procedure of immune absorption (blood washing) are available as second-line therapy options. In moderate or severe pemphigus vulgaris/foliaceus, systemic therapy with an anti-CD20 antibody (e.g., rituximab) in combination with prednisolone is recommended as induction therapy as an alternative to the treatment options already mentioned. A study published in 2017 showed that in patients with pemphigus vulgaris/foliaceus, the administration of rituximab can achieve healing of all skin and mucosal lesions in 90% of cases [2]. In the EU, rituximab is already approved for the treatment of moderate and severe pemphigus; in Switzerland, a marketing authorization application for this indication is currently being clarified by Swissmedic [5]. For the transition from induction to maintenance therapy, no new lesions should occur within a two-week consolidation phase and approximately 80% of the initial lesions should have healed [2].

Conclusion of a retrospective study: disease control is achievable

An analysis of patient data published in 2020 by researchers at Charité Universitätsmedizin Berlin and University Hospital Schleswig-Holstein found that the majority of patients achieve good disease control within a two-year period, but that there are large individual differences in terms of goal-directed treatment strategies [6]. The investigators retrospectively examined data from 77 pemhigus patients (81% pemphigus vulgaris, 19% pemphigus foliaceus) with repeated consultations regarding medication, dosage, disease activity, reason for a change in therapy, and autoantibody concentrations. The analysis showed that 86% of patients achieved disease control (“almost lesion-free” or “lesion-free”) after an average of 2 years of treatment, with a mean of four different treatment regimens used during this period. The large scatter of data reflects the variability of disease and treatment courses, with the duration to disease control ranging from 0 to 11 years and the number of therapy changes ranging from 1 to 18. The researchers also found that the levels of anti-desmoglein 3 and anti-desmoglein 1 correlated with disease severity but not with the number of therapy changes. In conclusion of their study, the authors summed up that identifying an effective and safe therapy for the individual pemphigus patient is challenging and often requires patience. Predictive parameters to predict treatment response are needed to optimize patient-adapted treatment options, he said.

For information on implications of corona pandemic for pemphigus disease, please refer to www.pemphigus.org.

Source: FomF (D) Dermatology and Allergy 2020

Literature:

- Worm M: Recognizing and treating blistering dermatoses. Prof. Dr. med. Margitta Worm FOMF Dermatology and Allergology Refresher, Hofheim (D), 11.09.2020.

- AWMF: Diagnosis and therapy of pemphigus vulgaris/foliaceus and bullous pemphigoid. Registration number 013-071. www.awmf.org

- Dermatology practice in the Alleecenter Remscheid (D), www.hautaerzte-remscheid.de/faq-15/autoimmunerkrankung-pemphigus-vulgaris.html

- Center for Bullous Autoimmune Dermatoses: Therapy of Bullous Autoimmune Dermatoses, University Hospital Schleswig-Holstein, Clinic for Dermatology Allergology and Venerology (Department of Dermatology), www.uksh.de

- Swissmedic: Swissmedic Journal 07/2020, www.swissmedic.ch (last accessed Feb. 17, 2021).

- Scarpone R, et al: Therapy Changes During Pemphigus Management: A Retrospective Analysis. Frontiers in Medicine 2020; https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2020.581820

- Mindorf S, et al: Routine detection of serum antidesmocollin autoantibodies is only useful in patients with atypical pemphigus. Exp Dermatol 2017; 26(12): 1267-1270.

- Xuan RR, Yang A, Murrell DF: New biochip immunofluorescence test for the serological diagnosis of pemphigus vulgaris and foliaceus: A review of the literature. International journal of women’s dermatology 2018; 4(2): 102-108. Epub 2018/06/07

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2021; 31(1): 41-43 (published 2/23/21, ahead of print).