Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a common inflammatory skin disease that affects both children and adults. The diagnosis is made using clinical criteria. Restoration of the skin’s barrier function and control of inflammation are the pillars of the treatment. This article shows how these general treatment principles can be adapted individually, which is essential given the extreme variability of AD manifestations.

The following clinical criteria are decisive for the diagnosis of atopic dermatitis (AD): eczematous skin changes at typical sites and age distribution, association with other allergic diseases such as rhinoconjunctivitis and bronchial asthma, positive family history for atopic diseases and itching.

Dual therapeutic approach: “relipidation” and inflammation inhibition

AD, as a chronic disease that mostly progresses in flare-ups, is based on a genetic predisposition with regard to the properties of the skin barrier on the one hand, and the type and course of inflammation on the other. The various disorders of the epithelial barrier known to date mean that the skin does not sufficiently perform its defense functions towards the outside world, e.g. e.g. against microbes, allergens and irritants. Mutations in filaggrin, a structural protein of corneocytes, as well as changes in cell adhesion and a deficiency in antimicrobial peptides were also identified. The keratinocytes and the immune system consider the penetration of pathogens as a potential danger, which leads to the release of alarmines. An inflammatory skin reaction is initiated in which different cells and cytokines participate. The T helper 2 profile with participation of T and B cells, eosinophils and interleukins (IL) 5 and 13 is typical of AD. Restoring the skin’s barrier function and controlling inflammation are therefore the mainstays of AD treatment. In practice, this means firstly a systematic background treatment with a “relipidizing” effect and secondly an effective anti-inflammatory treatment with topical corticoids and calcineurin inhibitors.

Individualized treatment

Daily clinical practice reveals that patients present with different manifestations of AD: inflamed or lichenized skin, localization of eczema in the folds, hands or face, children and adults, level of severity ranging from mild to severe, evolution by flare-ups or continuous, with or without association with allergic diseases, varying intensity of itching and variable influence of triggering factors. It is therefore necessary to adapt the general therapeutic principles individually.

Topical corticosteroids are the preferred medication during acute flare-ups, although their potency and/or frequency of use may be reduced if the skin condition improves. In case of long-term treatment with corticosteroids, intermittent treatment can be prescribed with an application once a day for three days, followed by four days with the background treatment with a relipidizing effect only. Topical calcineurin inhibitors (pimecrolimus, tacrolimus) are a good alternative for the treatment of flare-ups in mild to moderate forms of AD and for long-term treatment. Recent studies have shown the effectiveness and safety of these substances in children over a five-year treatment period. The risk of lymphoma and carcinoma is not increased in patients treated with topical calcineurin inhibitors.

Treatment should be tailored if particular areas are affected by AD: p. e.g., weak corticosteroids or topical calcineurin inhibitors for facial or eyelid involvement, medium to strong corticosteroids for hand or foot eczema

The skin of most AD patients is colonized by bacteria that play a role in pathogenesis, such as staphylococcus aureus. Therefore, daily showering or bathing and the use of disinfecting cleansers should be part of the treatment regimen. Afterwards, it is advisable to rehydrate the skin by applying a cream. Treatment with systemic antibiotics is only indicated in case of severe superinfection.

In particular, patients with severe AD who are prone to superinfection are regularly affected by complications such as herpetic eczema. Since skin barrier disorders and skin inflammation are prerequisites for the spread of herpes viruses, systematic lipid-replenishing and anti-inflammatory treatment is the most important measure for the prevention of eczema herpetica. A systemic treatment, p. e.g. valaciclovir, is necessary in cases of acute proliferation.

In severe cases, UV radiation (UV A1, UV B), also in combination with topical corticosteroids, is considered if the AD responds poorly or not at all to topical treatment. The indication for systemic therapy should not be delayed in these patients because they suffer greatly and their quality of life is significantly diminished. We first use cyclosporine at a dose of 3-5 mg/kg CP under continuous monitoring of blood pressure and laboratory parameters. If the patient does not respond to treatment or if there are contraindications, mycophenolate mofetil, methotrexate or azathioprine are also considered. The prescription of systemic corticosteroids is reserved for severe acute exacerbations, for a maximum of seven to ten days.

Some patients with AD suffer primarily from hand eczema. In addition to avoiding triggers such as contact with irritants and contact allergens, treatment with alitretinoin is also considered. Case series and our own observations show that not only the condition of the hands usually improves, but that other AD lesions also heal.

In a subset of patients, allergies trigger AD. Food allergens such as milk, eggs, wheat and peanuts are especially important in children. Dietary measures must be taken following a thorough allergological assessment. Blind diets” should be avoided. In adults, food allergies play a secondary role as triggers for AD flares. In particular, cross-allergens in fruits, vegetables and spices should be considered for people with pollen allergies. In addition to the respiratory tract, the skin of people allergic to house dust mites may also be affected, manifesting as eczema of the eyelids or face. Studies in recent years have shown that specific immunotherapy with house dust mite extracts leads to an improvement in AD.

The identification of patients with AD requiring specific therapy is currently done mainly by clinical criteria, with the exception of allergological diagnosis. To date, there are still no reliable biological markers for the diagnosis and treatment control of AD. Clinical experience shows that the spectrum of AD manifestations is very broad and that treatment must therefore be individually adapted. Improving our understanding of the pathogenesis of AD will allow us to treat it in an even more targeted manner.

In severe forms of AD, various biological compounds have been used in proof-of-concept studies; rituximab and alefacept have shown good results. IL-4/IL-13 or IL-13 receptor blockade as well as itch inhibition through IL-31 and histamine H4 receptor represent promising new strategies.

Patient Education

Patient-oriented treatment of AD involves, in addition to the individual treatment regimen, also patient education. A thorough understanding of the genesis of the disease and the necessary therapeutic measures are essential for successful treatment. In addition, this approach strengthens the doctor-patient relationship. In addition, patients must be empowered to manage their disease on a daily basis, p. e.g. in case of an acute attack. To do this, we have implemented the following program in our clinic:

- Neurodermatitis training in the form of interdisciplinary courses for patient groups

- Individual treatment training as part of our eczema consultations.

Neurodermatitis training is conducted by a team of dermatologists, allergists, psychologists, dieticians, care experts and relaxation therapists. In this context, patients not only receive theoretical and practical information, but can also discuss possible and reasonable strategies for coping with the difficulties that a chronic inflammatory disease entails in everyday life in discussions with experts and among themselves. Classes for adults are held twice a year at the Island Hospital. We also actively participate in the trainings for children and parents organized by aha! (see interview).

Patient education about the treatment is to be seen as an additional offer; its aim is to give the patient the ability to implement the treatment on a daily basis, to allow sufficient time for this, to know the products, to test the care products with regard to their skin-replenishing properties and acceptance, to apply the right amount and to react to a flare-up. From a variety of modules, those relevant to the patient in question are selected, presented to the patient on a flip chart or tablet, and explained in a hands-on training setting by a nurse. This form of patient education has proven to be very useful on a daily basis and is highly valued by patients. If a patient arrives p. e.g. with an acute exacerbation of AD, he will not only receive a prescription for the dermatological products he needs with the corresponding frequencies of use, but also practical instructions on when and how to apply them, including the use of oily-moist dressings. This form of patient education allows us to meet the individual needs of children, adolescents and parents.

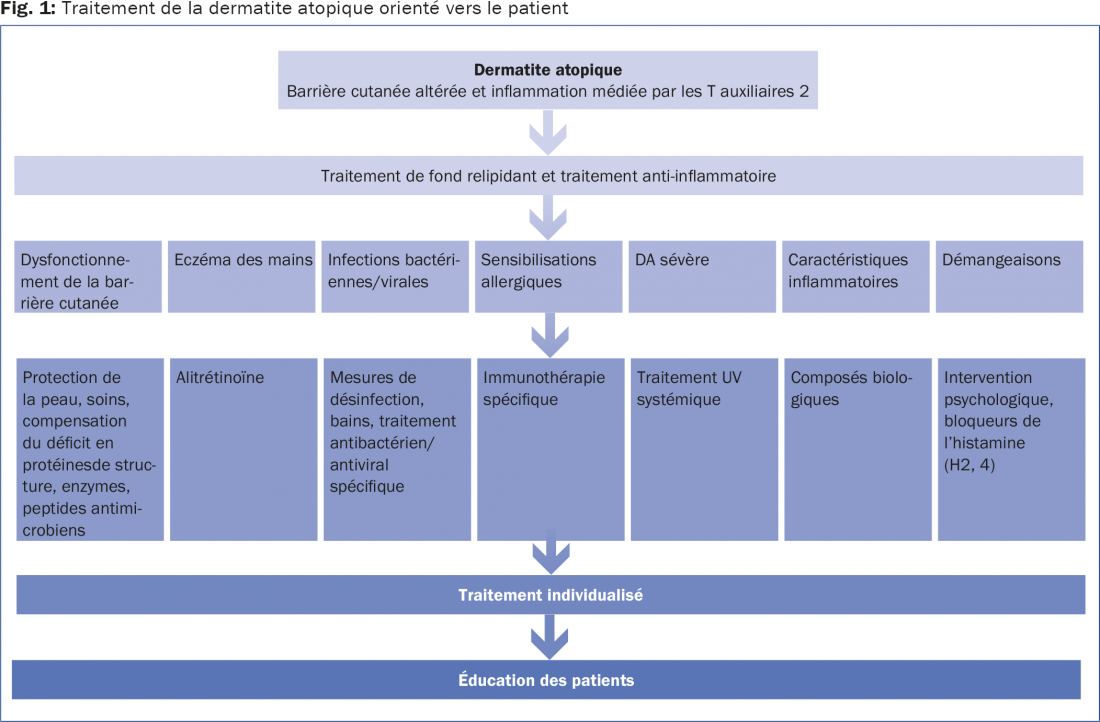

In our specialized consultation at the Island Hospital, patient-oriented treatment of AD implies individualized treatment from a pathogenetic point of view as well as patient education in daily clinical practice and courses. These requirements imply a permanent consideration of the latest developments and the adaptation of our program to current trends. To conclude, Figure 1 summarizes the different treatment subgroups and possible treatment approaches.

Conclusion for practice

- Restoration of the skin’s barrier function and control of inflammation are the mainstays of the treatment.

- Topical corticosteroids are preferred for acute flare-ups. In mild to moderate AD, however, topical calcineurin inhibitors (pimecrolimus, tacrolimus) are a good alternative for flare-ups and long-term treatment.

- Use low potency steroids or topical calcineurin inhibitors for facial or eyelid involvement; medium to high potency steroids for eczema of the hands or feet In the case of hand eczema, treatment with alitretinoin, in addition to avoiding triggers, also comes into play.

- Treatment with systemic antibiotics is only indicated in case of severe superinfection.

- In severe cases and if the AD responds insufficiently or not at all to topical treatment: UV radiation, also in combination with topical corticosteroids. The indication for systemic therapy should not be delayed in such patients.

- Patient education is also part of the patient-oriented treatment of AD.

Bibliographic references:

- Ring J, et al: European Dermatology Forum; European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology; European Task Force on Atopic Dermatitis; European Federation of Allergy; European Society of Pediatric Dermatology; Global Allergy and Asthma European Network: Guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) Part II. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2012 Sep; 26(9): 1176-1193.

- Ring J, et al: European Dermatology Forum (EDF); European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology (EADV); European Federation of Allergy (EFA); European Task Force on Atopic Dermatitis (ETFAD); European Society of Pediatric Dermatology (ESPD); Global Allergy and Asthma European Network (GA2LEN): Guidelines for treatment of atopic eczema (atopic dermatitis) part I. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2012 Aug; 26(8): 1045-1060.

- Simon D, Bieber T: Systemic therapy for atopic dermatitis. Allergy 2013 Dec 20.

- Novak N, Simon D: Atopic dermatitis – from new pathophysiologic insights to individualized therapy. Allergy 2011 Jul; 66(7): 830-839. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011. 02571.x. Epub 2011 Mar 3.

- Wechsler ME, et al: Novel targeted therapies for eosinophilic disorders. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012 Sep; 130(3): 563-571.

- Simon D, Simon HU: New drug targets in atopic dermatitis. Chem Immunol Allergy 2012; 96: 126-131.

- Luger T, et al: Recommendations for pimecrolimus 1% cream in the treatment of mild-to-moderate atopic dermatitis: from medical needs to a new treatment algorithm. Eur J Dermatol 2013 Dec 1; 23(6): 758-766.