Newly implanted cardiac resynchronization therapy with defibrillator (CRT-D) reduces the risk of morbidity and mortality in patients with left bundle branch block, heart failure and reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF). However, in HFrEF patients with right ventricular pacing (RVP), the efficacy of a CRT-D upgrade is uncertain. Dr. Béla Merkely presented the results of the BUDAPEST CRT upgrade study at the ESC Congress, in which patients with a conventional pacemaker or ICD were randomized to receive either a CRT-ICD upgrade or a standard ICD [1,2].

The estimated number of patients implanted with a pacemaker (PM) or implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) has exceeded one million devices per year worldwide and continues to rise due to the ageing population [3,4]. Within a few years of implantation, approximately 30% of patients with PM or ICD devices experience left ventricular (LV) systolic dysfunction due to right ventricular pacing-induced intraventricular dyssynchrony, resulting in a relatively high incidence of heart failure (HF) hospitalizations and associated adverse clinical outcomes [5–7]. In patients with HF and reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), wide QRS complex with left bundle branch block (LBBB) and without prior implantation of a pacemaker, a clear benefit of implanting a de novo device for cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) has been demonstrated [8–11]. Because RV pacing-induced dyssynchrony is comparable to intrinsic LBBB, patients with significant RV pacing and LV dysfunction appear to be at increased risk for further LV remodeling and adverse outcomes [5,6,12,13].

The current European guidelines recommend an upgrade to CRT in patients with a high RV pacing burden as a class IIa indication [8,14]. The 2023 Heart Rhythm Society/Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society/Latin American Heart Rhythm Society guidelines recommend biventricular pacing with a Grade B Class I for symptomatic high RV pacing stress and impaired LV function [15].

However, in patients with HFrEF and a previously implanted PM or ICD device, the potential benefit of upgrading to CRT in terms of hard outcomes has not been established, as there are no randomized controlled trials suitable for assessing this question and examining mortality and/or HF events [16]. In addition, previous data has shown that indicated upgrade procedures are often not performed or postponed to a later, undetermined date in >60% of candidates [17]. Since a significant proportion of patients with HFrEF and PM or ICD have a high RV pacing burden [18,19], the BUDAPEST-CRT study assumed that they are at risk of further negative LV remodeling and could benefit from a switch to CRT.

The BUDAPEST-CRT Upgrade study (Biventricular Upgrade on left ventricular reverse remodeling and clinical outcomes in patients with left ventricular Dysfunction and intermittent or permanent APical/SepTal right ventricular pacing Upgrade CRT) therefore compared the efficacy and safety of a CRT upgrade compared to ICD in HFrEF patients with a non-CRT PM/ICD and intermittent or permanent RV pacing [20]. It was hypothesized that an upgrade to cardiac resynchronization therapy with defibrillator (CRT-D) compared with an ICD-only upgrade would be associated with improved clinical outcomes, defined as risk of all-cause mortality, hospitalization for HF, or <15% reduction in LV end-systolic volume (LVESV) at 12 months.

CRT upgrade for heart failure with RV pacing

The prospective, multicenter, randomized, controlled phase III study included patients aged ≥18 years who had been implanted with a PM or ICD for at least six months and had all of the following characteristics: (i) reduced LV ejection fraction (LVEF, ≤35%), (ii) HF symptoms [New York Heart Association (NYHA) classes II-IVa], (iii) wide pacemaker QRS (≥150 ms) and (iv) ≥20% RV pacemaker load and treatment with guideline-directed medical therapy. Patients were excluded if they were eligible for CRT according to current guideline criteria (intrinsic LBBB), had severe RV dilatation (basal transverse RV diameter >50 mm on echocardiography), had evidence of severe valvular heart disease or severe renal dysfunction (creatinine >200 µmol/L). These patients often have a poor 1-year prognosis, which makes them questionable candidates for defibrillator therapy. In addition, patients who had survived an acute myocardial infarction or coronary revascularization in the previous three months were not included in the study.

Those who met the inclusion criteria were randomly assigned in a 3:2 ratio to a CRT-D upgrade or an ICD. Randomization was based on permuted blocks of five, stratified by center and generated via a web-based system. For the patients with a previously implanted ICD who were assigned to the ICD arm, there were two options: no procedure or CRT-D upgrade with CRT-D function turned off. Previously implanted RV stimulation electrodes could be extracted at the physician’s discretion.

Primary, secondary and tertiary endpoints

The primary endpoint was the composite of first occurrence of HF hospitalization, all-cause mortality within one year, or an echocardiographically determined reduction in LVESV of less than 15% from baseline to 12 months. Secondary endpoints were all-cause mortality and HF hospitalization, all-cause mortality alone, and reverse LV remodeling, defined as the echocardiographically determined change in LVEF or LV end-diastolic volume (LVEDV) between baseline and 12 months.

The tertiary endpoints included the success rate and the safety of the implantations. An independent evaluation committee assessed the HF hospitalization events in a blinded manner according to predefined definitions. Echocardiographic images were analyzed by the Echocardiographic Core Laboratory of Semmelweis University without knowledge of the treatment assignment.

Upgrading right ventricular stimulation to cardiac resynchronization therapy

Between 2014 and 2021, a total of 360 patients were enrolled at 17 sites in seven countries and randomly assigned to a CRT-D (n=215) or ICD upgrade procedure (n=145). The study population had a considerable number of concomitant diseases, in particular atrial fibrillation, a previous heart attack or diabetes. Almost half of the patients were hospitalized for HF within 12 months prior to inclusion in the study. Mean LVEF was 24.8 ± 6.6%, and more than two-thirds of patients had a PM device (predominantly DDD) implanted with high RV pacing.

Four (1.9%) patients assigned to the CRT-D arm failed the upgrade procedure due to failed LV lead implantation, while four (1.9%) patients in the CRT-D arm and one (0.7%) patient in the ICD arm were withdrawn prior to the procedure. The patients were observed for a median of 12.4 months. Twenty-seven patients (18.6%) switched from the ICD arm to CRT-D with activated biventricular pacing. A total of 12 (5.6%) patients in the CRT-D arm and 16 (11.0%) patients in the ICD arm died during follow-up.

At the end of the study, the vital status (dead or alive) of all patients was known, and all hospitalizations were reported by the center’s investigators, with no patient lost to follow-up. The changes in the echocardiographically determined parameters could not be analyzed in 36 patients in the CRT-D group and 17 patients in the ICD group.

The CRT-D upgrade reduces morbidity and mortality

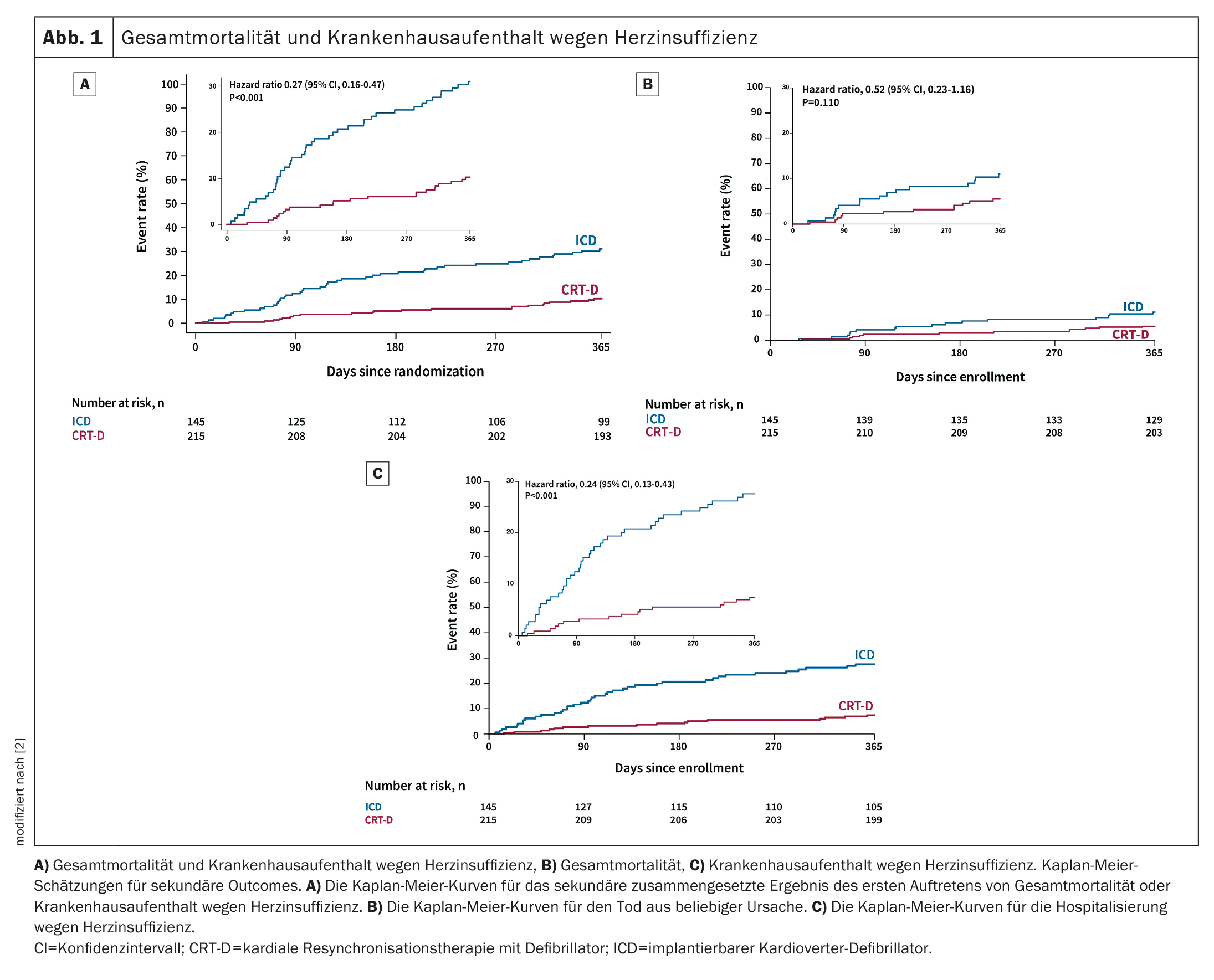

In the ITT population, the primary outcome occurred in 58/179 (32.4%) patients in the CRT-D arm and 101/128 (78.9%) in the ICD arm (adjusted OR 0.11; 95% CI 0.06-0.19; p<0.001). The composite of all-cause mortality and HF hospitalization (adjusted hazard ratio (HR) 0.27, 95% CI 0.16-0.47; p<0.001) (Fig. 1A) and the morphologic and functional response of the LV (difference after 12 months in LVEDV, -39.00 mL, 95% CI -51.73 to -26.27; p<0.001, and difference at 12 months in LVEF, 9.76%, 95% CI 7.55-11.98; p<0.001) spoke in favor of a CRT-D upgrade. There was no statistically significant difference in all-cause mortality between the two arms (adjusted HR 0.52, 95% CI 0.23-1.16; p=0.110) (Fig. 1B), indicating that the secondary composite endpoint was mainly driven by the reduction in HF hospitalization (adjusted HR 0.24, 95% CI 0.13-0.43, p<0,001) (Fig. 1C).

In terms of safety, the incidence of procedure- or device-related complications was similar in both groups (CRT-D group 25/211 [12%] vs. ICD group 11/142 [7,8%]). Lead extraction was performed in 32/211 (15%) of CRT-D and 16/142 (11%) of ICD upgrade procedures. The occurrence of serious ventricular arrhythmias was significantly lower in the CRT-D group (1/215 patients [0,5%]) compared to the ICD group (21/145 patients [14,5%]).

Switching to CRT has a major impact on HFrEF patients with high RV pacing burden

In the international randomized controlled trial involving patients with HFrEF and significant RV pacing with wide QRS complex, CRT-D upgrade reduced the composite primary endpoint of HF hospitalizations, deaths, and lack of reverse remodeling compared with ICD treatment alone. Cardiac resynchronization therapy with defibrillator upgrade was associated with significantly fewer HF hospitalizations or lower all-cause mortality compared to ICD treatment alone, with CRT-D associated with improved LV reverse remodeling.

“There has always been a question mark about whether or not CRT works for atrial fibrillation, and this study has shown that patients with chronic atrial fibrillation, permanent atrial fibrillation, may have a benefit,” said Dr. Béla Merkely, Director of the Heart and Vascular Center at Semmelweis University in Budapest, in a discussion after his presentation.

“The results will probably change the guidelines”

Cecilia Linde, Karolinska University Hospital, Stockholm, who served as discussant after Merkely’s presentation, pointed out that many patients receiving RV pacing therapy have been switched to CRT-D because improvement in symptoms has been demonstrated, but without solid evidence of an impact on hard outcomes. “This is why the BUDAPEST-CRT upgrade study, which focuses on the outcome, is extremely important,” she emphasized.

“Overall, we have very convincing results in favor of CRT,” Linde continued, pointing to the significant LV reverse remodeling associated with a reduction in ventricular arrhythmias, as well as the consistency between subgroups. “Switching from RV pacing to CRT-D improves outcome in pacemaker-induced cardiomyopathy,” she concluded. “An early upgrade to CRT can prevent a patient with left ventricular dysfunction from developing heart failure. So this will be a next step. The organization of device follow-up needs to be optimized to detect pacemaker-induced cardiomyopathy. I think the outcome is likely to have an impact on the guidelines.”

Literature:

- Merkely B: BUDAPEST CRT Upgrade: Cardiac resynchronization therapy upgrade in heart failure with right ventricular pacing – a multicentre, randomized, controlled trial. Hot Line Session 2, ESC Congress 2023, Amsterdam, 26.08.2023.

- Merkely B, et al: Upgrade of right ventricular pacing to cardiac resynchronization therapy in heart failure: a randomized trial. European Heart Journal 2023; https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehad591.

- Mond HG, Proclemer A: The 11th world survey of cardiac pacing and implantable cardioverter-defibrillators: calendar year 2009 – a World Society of Arrhythmia’s project. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2011;34: 1013-1027.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-8159.2011.03150.x. - Greenspon AJ, et al: Trends in permanent pacemaker implantation in the United States from 1993 to 2009: increasing complexity of patients and procedures. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;60: 1540-1545.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2012.07.017. - Lamas GA, et al: Ventricular pacing or dual-chamber pacing for sinus-node dysfunction. N Engl J Med 2002;346: 1854-1862.

https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa013040. - Wilkoff BL, et al: Dual-chamber pacing or ventricular backup pacing in patients with an implantable defibrillator: the Dual Chamber and VVI Implantable Defibrillator (DAVID) trial. JAMA 2002;288:3115–23. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.288.24.3115.

- Kiehl EL, et al: Incidence and predictors of right ventricular pacing-induced cardiomyopathy in patients with complete atrioventricular block and preserved left ventricular systolic function. Heart Rhythm 2016;13: 2272-2278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2016.09.027.

- Glikson M, et al: 2021 ESC guidelines on cardiac pacing and cardiac resynchronization therapy. Eur Heart J 2021;42: 3427-3520.

https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab364. - Moss AJ, et al: Cardiac-resynchronization therapy for the prevention of heart-failure events. N Engl J Med 2009;361: 1329-1338.

https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0906431. - Cleland JGF, et al: The effect of cardiac resynchronization on morbidity and mortality in heart failure. N Engl J Med 2005;352: 1539-1549.

https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa050496. - Bristow MR, et al: Cardiac-resynchronization therapy with or without an implantable defibrillator in advanced chronic heart failure. N Engl J Med 2004;350: 2140-2150. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa032423.

- Tang AS, et al: Cardiac-resynchronization therapy for mild-to-moderate heart failure. N Engl J Med 2010;363: 2385-2395. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1009540.

- Kosztin A, et al: De novo implantation vs. upgrade cardiac resynchronization therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart Fail Rev 2018;23: 15-26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10741-017-9652-1.

- Kusumoto FM, et al: 2018 ACC/AHA/HRS guideline on the evaluation and management of patients with bradycardia and cardiac conduction delay: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines, and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation 2019;140: e333-e81.

https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000627. - Chung MK, et al: 2023 HRS/APHRS/LAHRS guideline on cardiac physiologic pacing for the avoidance and mitigation of heart failure. Heart Rhythm 2023;20: e17-e91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2023.03.1538.

- Slotwiner DJ, et al: Impact of physiologic pacing versus right ventricular pacing among patients with left ventricular ejection fraction greater than 35%: a systematic review for the 2018 ACC/AHA/HRS guideline on the evaluation and management of patients with bradycardia and cardiac conduction delay: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society.

J Am Coll Cardiol 2019;74: 988-1008. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2018.10.045. - Essebag V, et al: Incidence, predictors, and procedural results of upgrade to resynchronization therapy: the RAFT upgrade substudy. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2015;8: 152-158. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCEP.114.001997.

- Cheung JW, et al: Trends and outcomes of cardiac resynchronization therapy upgrade procedures: a comparative analysis using a United States National Database 2003-2013. Heart Rhythm 2017;14:1043-50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2017.02.017.

- Linde CM, et al: Upgrades from a previous device compared to de novo cardiac resynchronization therapy in the European Society of Cardiology CRT Survey II. Eur J Heart Fail 2018;20: 1457-1468.

https://doi.org/10.1002/ejhf.1235. - Merkely B, et al: Rationale and design of the BUDAPEST-CRT Upgrade Study: a prospective, randomized, multicentre clinical trial. Europace 2017;19: 1549-1555. https://doi.org/10.1093/europace/euw193.

CARDIOVASC 2023; 22(4): 24-26 (published on 28.11.23, ahead of print)