Acute bronchitis often arises from an uncomplicated infection of the upper respiratory tract. A viral infection can be followed by a bacterial superinfection. While classic pneumonia is often self-limiting in healthy adults, people at risk can suffer from dangerous pneumonia. Vaccination against pneumonia, influenza and coronavirus is recommended for patients with risk factors. Otitis media is also usually preceded by a cold. Antibiotics are often not necessary, but in some cases they are.

Infections are a frequent reason for consultation in general medical practice. It is important to differentiate between infections that require treatment and self-limiting infections, to carefully select the appropriate anti-infective therapy and to identify complicating factors that may require inpatient treatment, explained Dr. Katja Römer, Gotenring Group Practice, Cologne (Germany) [1]. “Vaccinate your patients who are at risk against influenza and Covid, as this reduces mortality rates,” the speaker appealed. Various vaccines against respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) are currently under development [2].

Acute bronchitis or pneumonia?

Respiratory tract infections are viral in >90% of cases. Depending on the time of year, the following pathogens are particularly common: influenza A and B, RSV, rhinoviruses, parainfluenza viruses, coronaviruses (incl. SARS-CoV-2), human metapneumoviruses, boca/entero-/adenoviruses. With regard to antiviral drugs, Paxlovid® (nirmatrelvir/ritonavir) gained notoriety in connection with the coronavirus pandemic [3]. Treatment with the antiviral agent should be started within 5 days of the onset of Covid symptoms. Tamiflu® (oseltamivir) can reduce flu symptoms and prevent the spread of the virus, but should be given within the first 36 hours [3]. This period is already over for most patients due to swabbing or wait-and-see behavior when the question of an antiviral drug arises. Uncomplicated acute bronchitis should not be treated with antibiotics. In order for patients to understand this, explanations may be necessary. It is usually a self-limiting inflammation of the large airways/bronchi with a productive or non-productive cough lasting up to six weeks [4].

The disease is usually caused by cold viruses. Antitussives, NSAIDs and possibly inhaled steroids can be used for symptomatic treatment. Acute bronchitis is the most important differential diagnosis of pneumonia. Pneumonia can have many possible causes, the most common being bacterial pathogens, although pneumonia can develop as a result of a viral infection such as influenza or Covid-19 and, depending on age and general condition, can lead to serious complications (e.g. sepsis or lung failure). The CRB-65 index, which is derived from the following criteria [5], is calculated in the outpatient sector in order to identify patients at risk at an early stage and treat them appropriately:

- C: pneumonia-related confusion, disorientation to place, time or person

- R: Respiratory rate ≥30/min

- B: Blood pressure diastolic ≤60 mmHg or systolic <90 mmHg

- 65: Age ≥65 years

One point is awarded for each criterion determined, the highest possible score is 4.

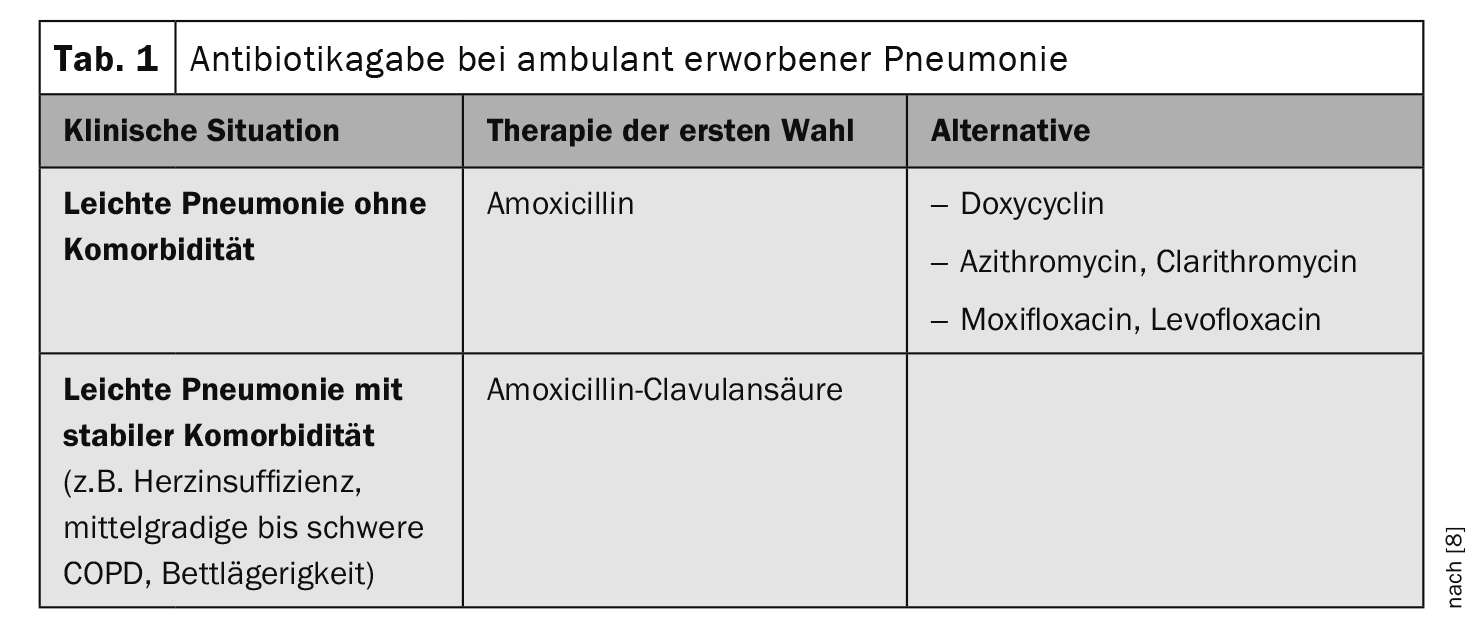

Antibiotic treatment with a substance effective against pneumococci is indicated unless there are indications to the contrary (Table 1) .

Vaccinating high-risk patients against pneumococci

“Bacterial infections are relatively rare,” says Dr. Römer [1]. Pertussis and pneumococcus are the most common. Whooping cough can also occur in adults, and pertussis immunity decreases with increasing age. Community-acquired infections also include chlamydia and mycoplasma. When it comes to vaccinations, not only pertussis should be considered, but vaccination against pneumococci could also be very important for people at risk (e.g. over 60 years of age), the speaker emphasized, adding: “Pneumonia with Streptococcus pneumoniae is relatively common in people at risk and is associated with a high mortality rate”. Information on the choice of antibiotics for the treatment of bacterial infections can be found in the box .

If patients approach their doctor after a few weeks of coughing with the expectation that he or she can do something about it, they should be informed about the course of the respective viral infection. The speaker illustrated this using the example of RSV: syncytia form in the upper airways. The regeneration of these epithelia takes 6 weeks. Therefore, 4 or 6 weeks is normal for self-limiting courses. But of course the general condition is decisive in assessing whether treatment measures are indicated.

| In Switzerland, the Sentinella statistics provide weekly overviews of respiratory viruses. |

| In addition to pertussis, vaccinations against pneumococcus and influenza are also part of the basic vaccinations for people at risk. |

| The pathogen spectrum of bacterial infections of the respiratory tract includes Bordetella pertussis, Legionella, Chlamydia pneumoniae, Mycoplasma pneumoniea, Moraxella catarrhalis, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae. |

| Pertussis can be treated with azithromycin or clarithromycin, legionellosis with levofloxacin, moxifloxacin or macrolides. The latter are also used to treat chlamydia and mycoplasma. |

| to [1,9] |

Simple penicillins are the first choice for tonsillitis

Tonsillitis is predominantly caused by Streptococcus pyogenes or beta-hemolytic streptococci of serological group A. These are skin colonizers; transmission occurs via droplet infection. “There are people who are particularly susceptible,” reported Dr. Römer [1]. Streptococcus pyogenes can also cause scarlet fever, impetigo contagiosa, toxic shock syndrome, erysipelas and other soft tissue infections. “Look down people’s throats,” recommends the infectiologist. There are also rapid streptococcal tests from various providers. “You can treat streptococci with simple penicillin,” emphasized Dr. Römer [1]. It is advisable to ask the patient about a possible penicillin allergy beforehand. In the case of allergies, clindamycin or macrolides can be used as an alternative. After two days of antibiotics, the patient should feel better, i.e. a re-evaluation should be carried out after 48 hours. If it hasn’t helped, you need to go back to the books and ask yourself whether it might be a viral infection after all.

Soft tissue infections such as erysipelas, impetigo contagiosa or sialadenitis are also caused by streptococci and can be treated with penicillin V, clindamycin, azithromycin or clarithromycin. CAVE for mixed infections or abscess formation. “As soon as you see an abscess anywhere, the surgeon has to get involved,” says the speaker [1].

Otitis media: often no antibiotics are needed

A middle ear infection usually affects children. Typical clinical manifestations are visible redness and bulging of the eardrum with tympanic effusion. “It is often a viral infection that has promoted this,” explained Dr. Römer [1]. These include, for example, previous viral infections with RSV, influenza, parainfluenza or rhino-/adeno-/enteroviruses. Bacterial pathogens from the following spectrum then play a role in the course of otitis media: Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Moraxella catharralis, Streptococcus pyogenes, Staphylococcus aureus [7]. But as the speaker emphasizes: “Antibiotics are not always necessary”. The standard treatment for otitis media is analgesia with an anti-inflammatory NSAID (e.g. ibuprofen, diclofenic) and decongestant nasal sprays to open the tubes. However, there are cases in which the administration of antibiotics** should be considered:

- Age <6. Month of life;

- Age <2. Year of life with bilateral otitis media and temperature <39.0°C;

- Acute otitis media with temperature ≥39.0ºC;

- persistent, purulent otorrhea;

- Risk factors (e.g. otogenic complication, immunodeficiency, severe underlying diseases, Down syndrome, cleft lip and palate, cochlear implant carrier, influenza)

- Progress cannot be monitored reliably within the first three days.

- If antibiotics are used, aminopenicillin (e.g. amoxicillin) is the first choice and cefuroxime, cefpodoxime or clarithromycin, azithromycin are the second or third choice. Here too, the response to antibiotic treatment should be evaluated after 48 hours.

** Antibiotics: 1st choice: aminopenicillin (e.g. amoxicillin); 2nd choice: Cefuroxime, Cefpodoxime; 3rd choice: Clarithromycin, Azithromycin; evaluation after 48 h, intensification of therapy if necessary

Congress: FomF General Medicine Refresher

Literature:

- “Bladder, bronchi, banal(?) – treatment of common infections”, Dr.med. K. Römer, FOMF General Medicine Refresher Cologne, 17-20.01.2024.

- “Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV)”, www.bag.admin.ch,(last accessed 24.01.2024)

- Swissmedic: Medicinal product information, www.swissmedicinfo.ch,(last accessed 24.01.2024)

- Harris AM, Hicks LA, Qaseem A: Appropriate Antibiotic Use for Acute Respiratory Tract Infection in Adults: Advice for High-Value Care From the American College of Physicians and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Annals of internal medicine 2016; 164(6): 42534.

- “CRB-65-Index”, https://flexikon.doccheck.com,(last accessed 24.01.2024)

- Thomas JP, et al: Acute otitis media – a structured approach. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2014 Feb 28; 111(9): 151-159; quiz 160.

- van der Linden M, et al: Bacterial spectrum of spontaneously ruptured otitis media in the era of pneumococcal conjugate vaccination in Germany.

Eur J Pediatr 2015; 174(3): 355-364. - Schäfer H: Procedure for community-acquired pneumonia in the family practice. MMW Fortschr Med 2022; 164(19): 40-43.

- “BAG-Bulletin 4/2024”, BAG, 22.01.2024.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2024; 19(2): 28-30 (published on 20.2.24, ahead of print)