Due to the special pathophysiology and the resulting therapy options, the general practitioner plays a decisive role in the diagnosis and therapy of neuropathic pain. Essential knowledge of clinical and instrumental diagnostics and therapeutic options should be familiar to every physician. It is not uncommon for it to be necessary to refer the patient to experts in neurology or neurosurgery or to an interdisciplinary, multimodal pain practice or clinic.

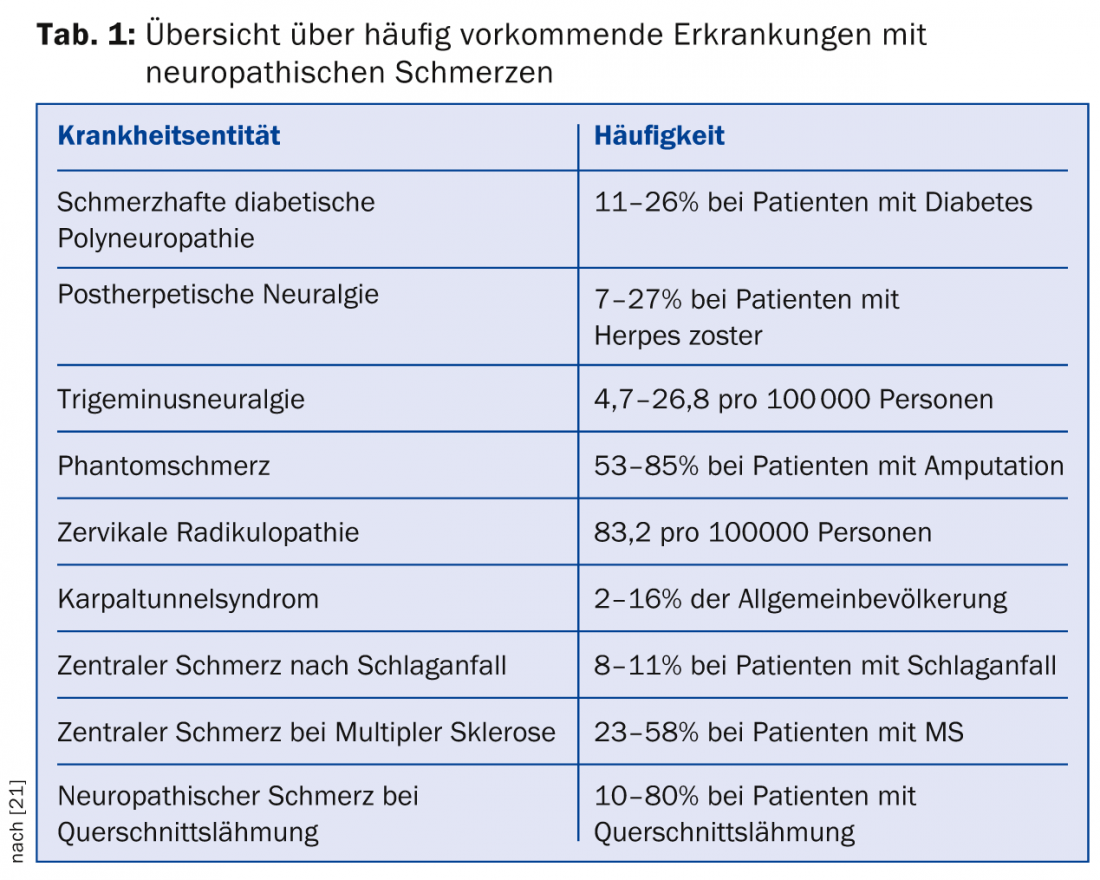

The prevalence of neuropathic pain in general practice is approximately 8%; this high prevalence underscores the importance of the primary care physician in the diagnosis and treatment of these symptoms [1]. An overview of the prevalence of common conditions associated with neuropathic pain is given in Table 1.

How is neuropathic pain defined?

Neuropathic pain is defined according to the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) as “pain caused by a lesion or disease of the somatosensory system” [2]. The somatosensory system is that part of the nervous system that processes information from skin, joint, and muscle receptors and mediates the perception of sensory qualities such as pressure, touch, pain, and temperature. It involves the peripheral afferent nerves, their central pathways of conduction, and the processing centers such as the thalamus and somatosensory cortex.

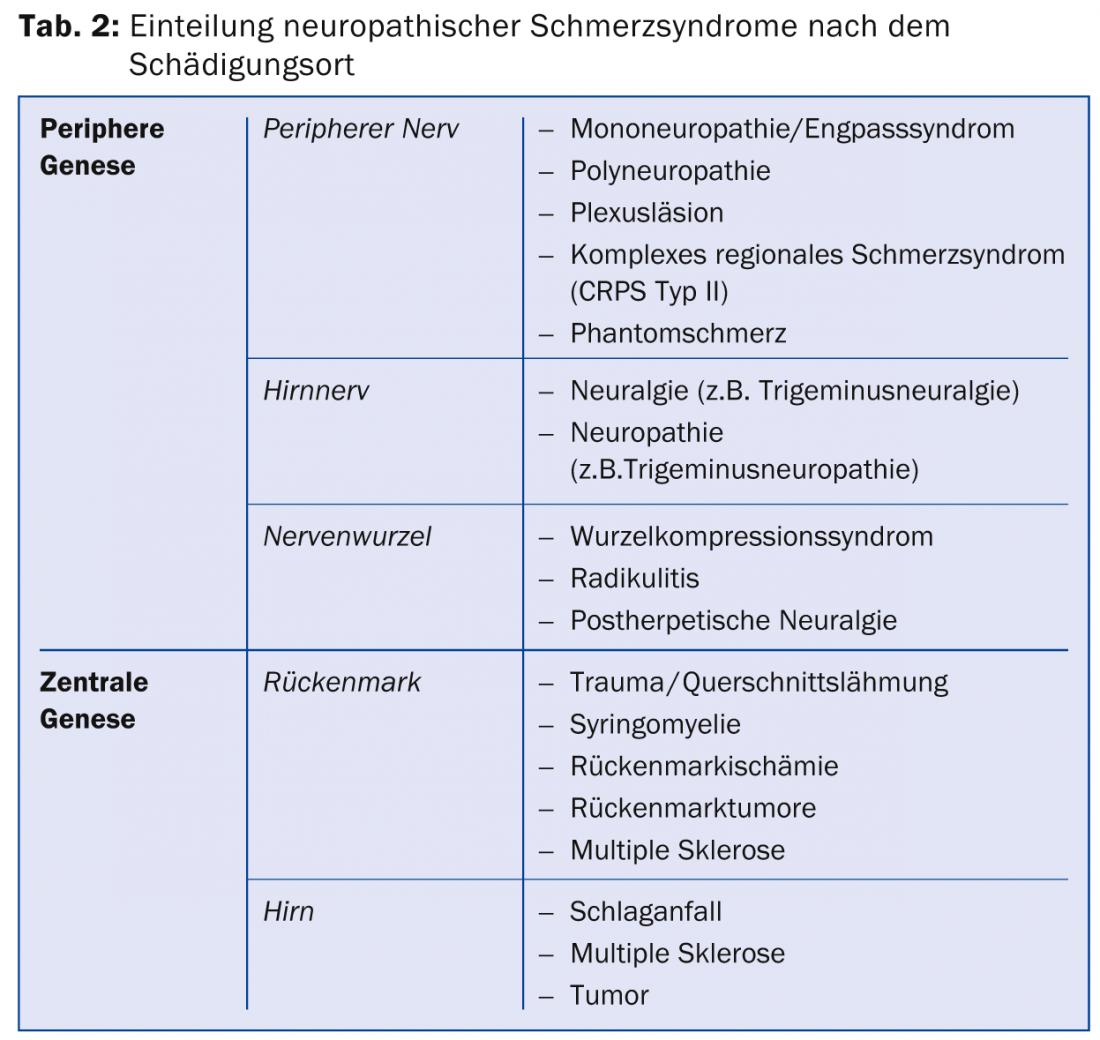

Depending on the location of the nerve lesion, this results in certain neuropathic pain syndromes (Tab. 2) . The cause may vary depending on the disease.

A special form is the complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) of type I, i.e. without detectable nerve damage. According to the new diagnostic criteria mentioned above, it can no longer be clearly classified as a neuropathic pain syndrome because the location of the nerve lesion is unclear, although a number of indications of neuropathic phenomena are present. Therefore, specific diagnostic criteria are applied by considering anamnestic information and clinical findings regarding allodynia, hyperalgesia, abnormalities of skin temperature, skin color, sweating, edema formation, motor function, and nail and hair growth in the pain area in lateral comparison without certain dermatomal distribution [3]. In CRPS type II, the symptoms are identical, but an initial nerve lesion can be demonstrated.

From pathomechanism to neuropathic pain

A lesion (e.g., pressure lesion of the nerve root due to disc herniation) or disease (e.g., damage to nerve fibers due to hyperglycemia in diabetes) affecting the somatosensory system is associated with the release of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and neurotrophic factors such as NGF. This release leads to the formation of ion channels such as Na+ channels or even receptors such as TRPV1 or NA (norepinephrine) receptors, both on damaged and neighboring healthy neurons. As a result, phenomena corresponding to neuropathic pain occur. For example, accumulation of Na+ channels leads to the development of so-called spontaneous ectopic nervous excitation, which is clinically manifested as electrifying and shooting-in pain when pain-conducting C and A-δ fibers are involved. When A-β fibers that mediate mechanical stimuli are affected, ectopic nerve excitation may manifest only as tingling sensations.

The TRPV1 receptor is involved in the mechanism of peripheral sensitization. Clinically, this sensitization may manifest as burning constant pain or heat hyperalgesia. As a result of the continuous ectopic signaling of the damaged C-fibers, so-called central sensitization also occurs at the site where the peripheral pain fiber in the posterior horn of the spinal cord is switched to the central pain pathway (anterior cord). Adaptation mechanisms such as increased accumulation of Ca++ channels as well as NMDA receptors lead to signal amplification, for example, painful increased spiking sensation, Prinprick hyperalgesia, or painful touch sensation, allodynia [4,5].

Diagnosis of neuropathic pain

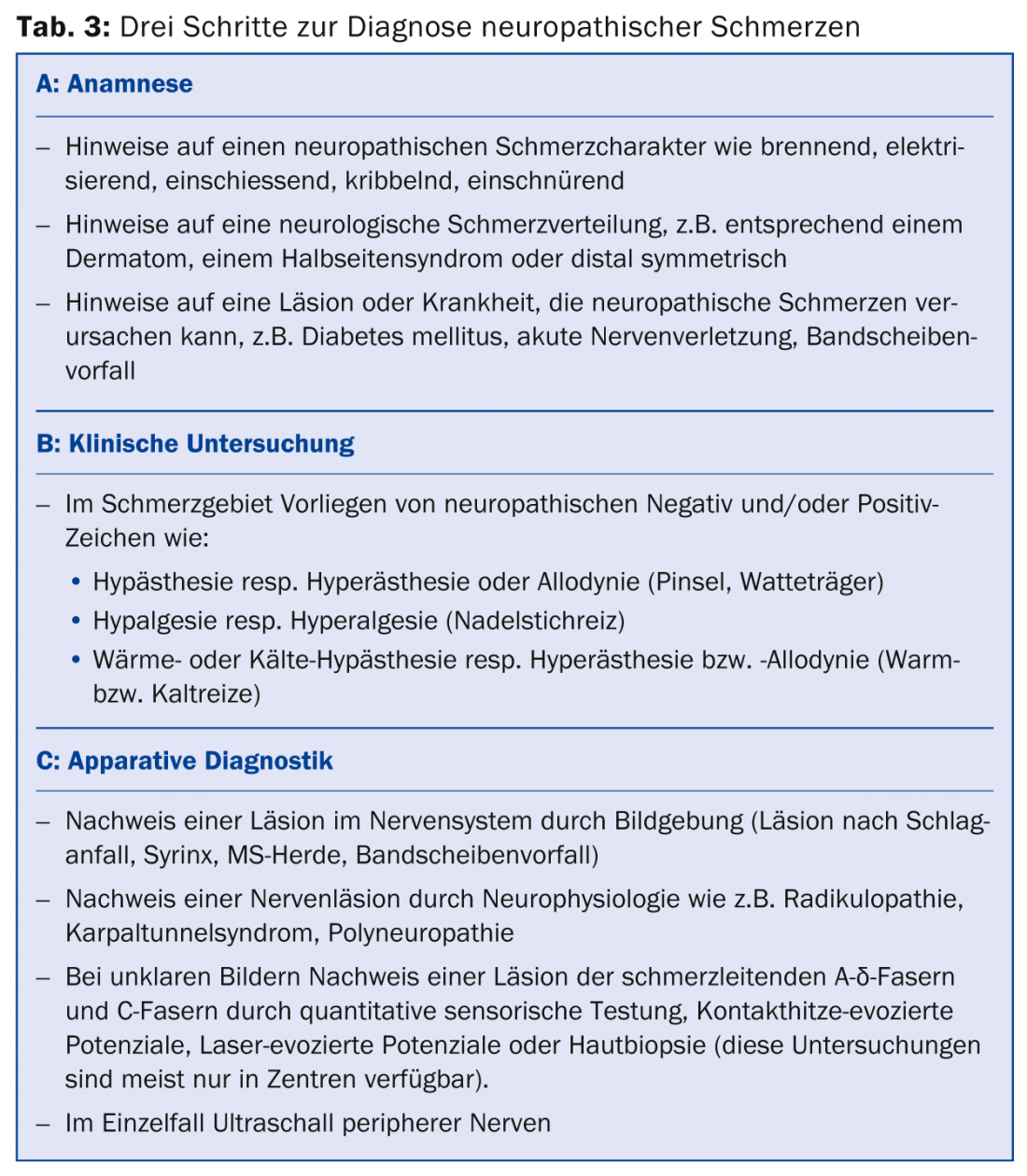

In every pain patient in clinical practice, the pain pattern should be questioned for evidence of neuropathic pain mechanisms. According to the European guidelines for the diagnosis of neuropathic pain, attention should be paid to the following points (Tab. 3) [6].

History: The pain character should be checked in the history for evidence of neuropathic signs (burning, electrifying, tingling, constricting). Furthermore, it is examined whether the localization corresponds to a neurologically plausible distribution (e.g., dermatomal distribution, hemiparesis syndrome, distal symmetric distribution). Likewise, a lesion (e.g., evidence of disc herniation) or a disease (e.g., diabetes mellitus) that is likely to cause neuropathic pain syndrome should be sought.

Clinical examination: the clinical examination involves looking for sensory positive or negative signs for the different somatosensory qualities. The suspect pain area is examined for increased or decreased touch sensation (e.g., with cotton swab, brush), increased or decreased pain sensation (e.g., with pinprick stimulus), or increased or decreased temperature sensation (e.g., with cold stimulus). If there is a history of polyneuropathy, the examination is performed by comparing proximal (thigh) versus distal (dorsum of foot) [7].

Apparative diagnostics: Further diagnostic tests may be performed to verify the underlying neurological dysfunction, for example, imaging for suspected pain after stroke or suspected disc herniation, or neurophysiological testing to confirm a nerve lesion (e.g., suspected radiculopathy, carpal tunnel syndrome, or polyneuropathy).

The more evidence there is, the more confidently the suspected diagnosis of neuropathic pain can be assessed. If the diagnosis is uncertain or unclear, the patient should present to a neurologist or pain center. Special diagnostic tools are available in pain centers, such as quantitative sensory testing (QST), contact heat-evoked potentials (CHEPS), laser-evoked potentials (LEP), or skin biopsy, which can be used, for example, to examine the function of small, pain-conducting nerve fibers such as A-δ fibers and C fibers and to confirm or invalidate the diagnosis of neuropathic pain [7,8]. Ultrasound is becoming increasingly important in the search for a focal nerve lesion of peripheral nerves [9].

Important differential diagnosis nociceptive vs. neuropathic

Initially, a patient may present with a circumscribed problem such as back and leg pain. Clinical examination suggests radiculopathy with evidence of disc herniation on MRI. Although diagnosis and therapy seem simple here, the view should always go further. It is not uncommon to find that what at first glance appears to be a monosymptomatic clinical picture is only the tip of a multilocular, chronic pain disorder; it is possible that several back operations have already been performed, for example. In the chronic pain patient, therefore, the diagnosis of neuropathic pain with radiculopathy, which was clear at the outset, can play rather a subordinate role, since further biopsychosocial aspects of pain chronification are added, which is shown by the fact that the therapy options known to us have little effect.

Biological factors may be the initial neurological event that acquires a myofascial or nociceptive component in the course with muscular factors as a result of restraint and poor posture. Psychological factors are, for example, a resulting depressive development and inadequate concepts of illness, social factors reflect the interaction of pain in professional and private life. In this context, the differential diagnosis regarding nociceptive, myofascial pain is important. An attempt should always be made to work out the nociceptive pain component.

Indications of nociceptive pain are pain that is intensified or attenuated depending on movement or that changes with position. Pressure tenderness of musculoskeletal structures is usually found, but evidence of skeletal-related pathology is not always found on imaging. Typically, patients describe the pain as dull, pressing, or pulling. One should critically question the indication of burning pain, since this description is not pathognomonic for neuropathic pain – often myofascial pain is also described as burning.

Sudden onset pain must also be differentiated: Shooting pain on movement only tends to correlate with nociceptive pain, whereas neuropathic shooting pain typically occurs at rest, especially in the evening or at night. This important distinction is reflected in the recent literature, in which a number of proposals exist for pain classification in various neurological disorders, for example, pain classification in stroke [10], in paraplegia [11], and in multiple sclerosis [12]. These classifications underscore that even with underlying neurologic disease, pain does not necessarily have to be neuropathic.

The syndrome of persistent post surgical pain (PPSP), which is increasingly discussed in the literature, has a special status [13]. PPSP, with an incidence of 14.8% after surgical procedures, is pathophysiologically poorly understood and has both nociceptive and neuropathic aspects [14,15]. The syndromes known to us, such as postmastectomy pain, postthoracotomy pain, postherniotomy pain, and others are included in this category.

Multimodal therapeutic aspects

If a complex pain pattern is present, the individual pain components must also be treated in a specialist manner or the patient must be referred to an interdisciplinary and multimodal pain practice or to a specialist pain clinic. -clinic can be referred. In terms of therapeutic priorities, antineuropathic drug therapy, physical therapy, and psychological pain management should be given equal weight. In addition, interventional pain therapy can make an important contribution diagnostically and therapeutically. However, current data indicate that the efficacy of interventional pain medicine interventions is based on weak evidence [16], so these therapeutic interventions should be performed in pain practices or clinics with expertise in this area. For example, there are only weak recommendations for epidural injections for herpes zoster, steroid injections for radiculopathy, and the application of a spinal cord stimulator for the so-called “failed back surgery syndrome” (unchanged back and leg pain after back surgery), respectively. in CRPS type I. Data are inconclusive for a number of interventional therapies for various medical conditions [16].

Basics of drug therapy

The pathophysiological mechanisms can be exploited pharmacotherapeutically by using Na+ antagonists (e.g., carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, lamotrigine), Ca++ channel modulators (gabapentin, pregabalin), or even TRPV1 antagonists (capsaicin) to target neuropathic pain. Furthermore, the descending, inhibitory, spinal pathways, which originate in the brainstem and inhibit the transmission of pain stimuli in the spinal cord, can be used therapeutically. Tricyclics (amitriptyline) and serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (duloxetine, venlafaxine) relieve pain by enhancing this inhibition. Opiates inhibit the conduction of pain signals via binding to µ or kappa receptors, so they can also be used to treat neuropathic pain. Newer opiates such as tapentadol and buprenorphine may be superior to conventional opiates because tapentadol has an additional descending inhibitory effect (binding to norepinephrine receptors) and buprenorphine has an additional K+ channel blocking property. Tramadol also additionally inhibits the descending inhibitory pathways. Lidocaine 5% gel, which acts as an Na+ channel blocker, can be applied as a topically applied substance for circumscribed painful mononeuropathies such as postherpetic neuralgia.

Depending on the underlying pain mechanism, causal therapies should also be considered, such as optimal glycemic control in diabetics or surgical interventions (Janetta surgery for trigeminal neuralgia, decompression for herniated disc).

The goals of drug therapy are to reduce pain by more than 50%, improve sleep quality, maintain social activity and social relationships, and maintain the ability to work. This requires titration of antineuropathic drugs, taking into account the effect and side effect, with sufficient duration of therapy and sufficiently high dose. Combination therapies of different drug groups are also frequently necessary.

Drug therapy of peripherally and centrally generated neuropathic pain

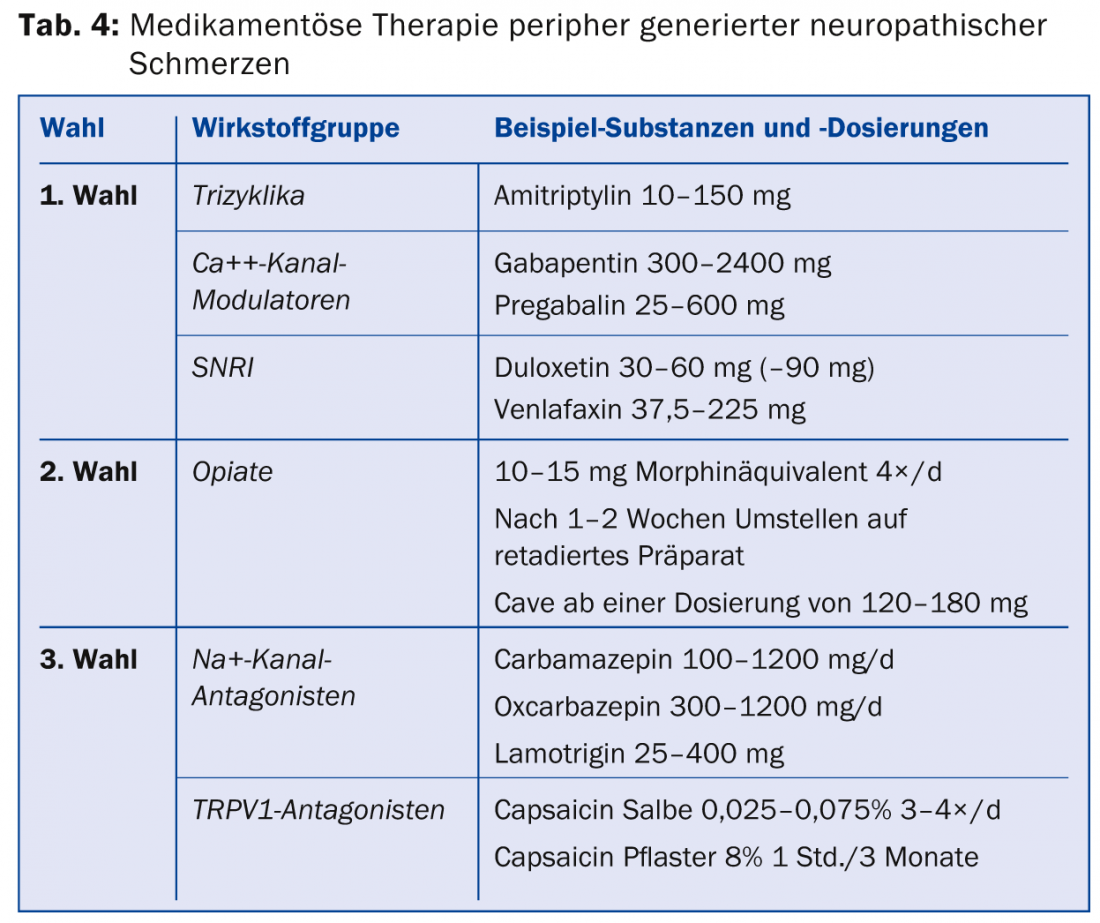

The current Swiss guidelines for the treatment of neuropathic pain [7] are in line with the international guidelines [17,18]. For general therapy of peripherally generated neuropathic pain, tricyclics, calcium channel modulators, and selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) are available as first-line therapeutic agents (Table 4) [17]. Opiates can be used as second-line medications. In terms of efficacy, opiates do not differ from first-line medications, but they have a higher rate of side effects in comparisons with tricyclics and gabapentin, and there is a risk of possible opiate-induced hyperalgesia or development of opiate dependence.

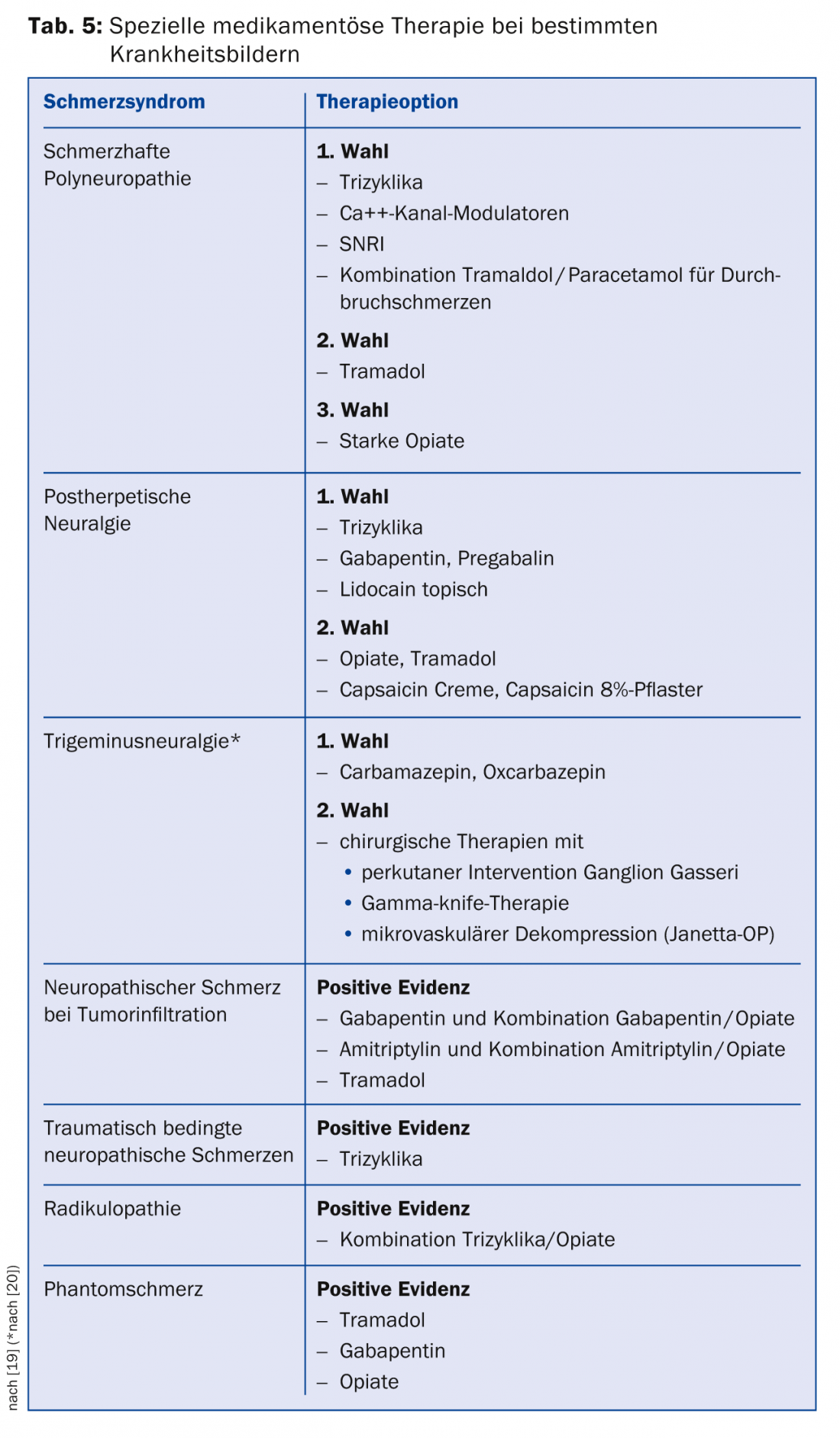

If these medications do not adequately relieve pain, third-line therapeutics are available for which only one positive study is available or the data are inconsistent. Representatives of this class are Na+ channel antagonists, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), lidocaine analogues, and also capsaicin. In Switzerland, capsaicin (8% patch) is approved for the treatment of peripheral neuropathic pain in adults who do not have diabetes. For reimbursement by the health insurance company, an application for cost approval must usually be submitted. Capsaicin should be applied in pain practices. Special recommendations exist for individual clinical pictures (Tab. 5) [19].

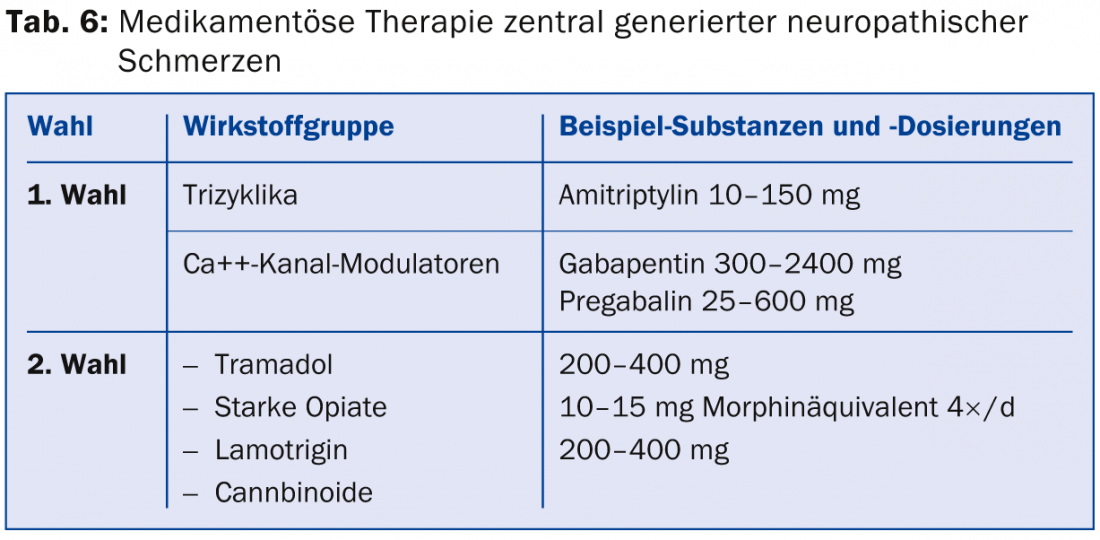

For the treatment of centrally generated neuropathic pain, options are more limited [8]. First-line therapeutic agents available for post-stroke pain are tricyclics, and for post-spinal cord lesion pain are Ca++ channel modulators. Second-line medications include tramadol and strong opiates and lamotrigine for stroke and incomplete paraplegia with allodynia, and cannabinoids for multiple sclerosis, but only after failure of other therapies (Table 6) .

If these medications are not effective or contraindications exist, first- and second-choice medications for peripherally generated neuropathic pain may be resorted to.

Conclusion for practice

- Knowledge of sensory positive and negative signs is important for clinical diagnosis of neuropathic pain.

- The suspected diagnosis of neuropathic pain should be made in the primary care physician’s office.

- Neurological clarification is often indicated to confirm the diagnosis, and referral to an interdisciplinary pain practice or clinic is indicated in cases that are unclear or resistant to treatment.

- The differential diagnosis between nociceptive and neuropathic pain also plays a role in primary neurologic disorders.

- Treatment of neuropathic pain often requires an interdisciplinary and multimodal team.

- Tricyclics, SNRIs, and Ca++ channel modulators are available for first-line therapy of peripherally generated neuropathic pain.

- For the treatment of centrally generated neuropathic pain, the first-line options are tricyclics and Ca++ channel modulators.

- Although the evidence for interventional pain management is limited, it can aid in the diagnostic and therapeutic management of pain patients.

Literature:

- Torrance N, et al: The epidemiology of chronic pain of predominantly neuropathic origin. Results from a general population survey. The journal of pain: official journal of the American Pain Society 2006; 7(4): 281-289.

- Treede RD, et al: Neuropathic pain: redefinition and a grading system for clinical and research purposes. Neurology 2008; 70(18): 1630-1635.

- Harden RN: Proposed new diagnostic criteria for complex reghilan pain syndrome. Pain medicine 2007; 8(4): 326-331.

- Baron R: Neuropathic pain. Anesthesiologist 2000; 49: 373-386.

- Baron R, Freynhagen R: Compendium of neuropathic pain. 2nd edition, Aesopus Publishing House, 2006.

- Cruccu G, et al: EFNS guidelines on neuropathic pain assessment: revised 2009. Eur J Neurol 2010; 17(8): 1010-1018.

- Renaud R, et al: Chronic neuropathic pain Recommendations of the Special Interest Group (SIG) of the Swiss Society for the Study of Pain (SGSS). Swiss Medical Forum 2011; 11(Suppl. 57): 3-19.

- Gosrau G, et al: Electrophysiological measurement techniques in pain therapy. Pain 2008; 22: 471-481.

- Böhm J, Schelle T: Value of high-resolution sonography in the diagnosis of peripheral nerve diseases. Act Neurol 2013; 40(05): 258-268.

- Klit H, et al: Central post-stroke pain: clinical characteristics, pathophysiology, and management. Lancet Neurol 2009; 8(9): 857-868.

- Bryce TN, et al: International spinal cord injury pain classification: part I. Background and description. Spinal Cord 2012; 50(6): 413-417.

- Truini A, et al: Mechanisms of pain in multiple sclerosis: a combined clinical and neurophysiological study. Pain 2012; 153(10): 2048-2054.

- Werner MU, Kongsgaard UE. Defining persistent post-surgical pain: is an update required? Br J Anaesth 2014; 113(1): 1-4.

- Simanski CJ, et al: Incidence of chronic postsurgical pain (CPSP) after general surgery. Pain medicine (Malden, Mass) 2014; 15(7): 1222-1229.

- Haroutiunian S, et al: The neuropathic component in persistent postsurgical pain: a systematic literature review. Pain 2013; 154(1): 95-102.

- Dworkin RH, et al: Interventional management of neuropathic pain: NeuPSIG recommendations. Pain 2013; 154(11): 2249-2261.

- Dworkin RH, et al: Pharmacologic management of neuropathic pain: evidence-based recommendations. Pain 2007; 132(3): 237-251.

- O’Connor AB, Dworkin RH: Treatment of neuropathic pain: an overview of recent guidelines. Am J Med 2009; 122(10 Suppl): S22-32.

- Attal N, et al: EFNS guidelines on the pharmacological treatment of neuropathic pain: 2010 revision. Eur J Neurol 2010; 17(9): 1113-1188.

- Cruccu G, et al: AAN-EFNS guidelines on trigeminal neuralgia management. Eur J Neurol 2008; 15(10): 1013-1028.

- Sadosky A, et al: A review of the epidemiology of painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy, postherpetic neuralgia, and less commonly studied neuropathic pain conditions. Pain practice: the official journal of World Institute of Pain 2008; 8(1): 45-56.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2015; 10(1): 14-21