The number of people with MS in Switzerland is increasing. Current surveys paint an alarming picture. This makes effective treatment that is individually adapted to the patient’s life situation and disease progression all the more important. The goal should be to maintain participation in social life for as long as possible.

Until now, it was assumed that there are about 10,000 people living in Switzerland who have multiple sclerosis (MS). A recent survey by the MS Registry has now had to revise this assumption: at least 15,000 people suffer from the disease – and the trend is still rising [1]. The gender ratio is also shifting even further in the direction of women. New projections put the number of affected women at 73%. Whether this development is due solely to population growth and increased life expectancy is open to doubt. The mechanisms by which the disease develops are still being deciphered. Preliminary results indicate a genetic disposition and a significant influence of environmental factors. Current research focuses, among other things, on neurodegeneration [2,3]. It is largely responsible for the development of disabilities due to axonal transection and loss of neurons. Increasing neurodegeneration, which most likely starts earlier than previously thought, seems to be a major cause of disease progression. The exploration of biomarkers, such as the neurofilament light protein, which detects axonal or general neuronal damage and can be used to better assess the prognosis of the individual patient, are first promising steps towards personalized therapy [4].

Clinically, relapsing-remitting can be distinguished from primary and secondary progressive courses. In addition to neurological symptoms, many patients suffer from cognitive deficits, fatigue and manifest depression. Since MS manifests itself in different forms and facets, the treatment management should be correspondingly comprehensive, competent and individually adapted to the patient.

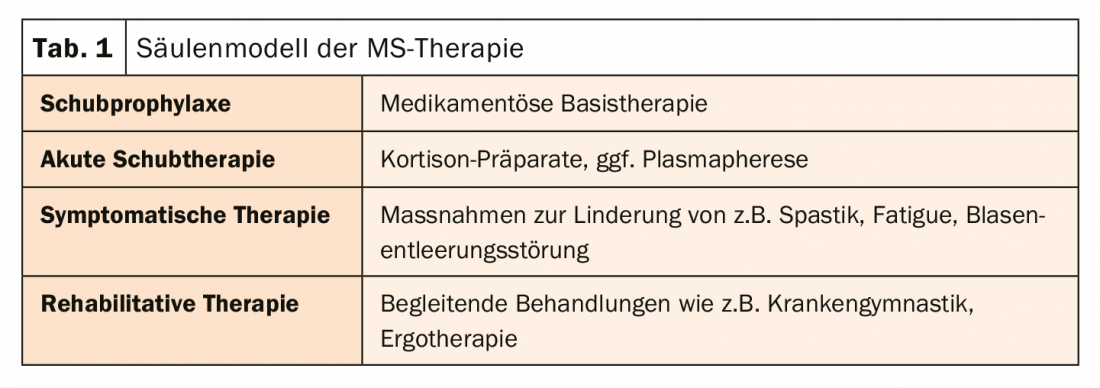

Pillar model as a basis for therapy

The earlier therapy can be initiated, the better. Several effective treatment options are now available that can often greatly slow the progression of the disease. Basically, the therapy should be based on four pillars (tab. 1). The aim of treatment is to reduce the extent of the inflammatory reactions, stabilize the functional limitations and improve the accompanying symptoms. A NEDA(No Evidence of Disease Activity)-3 status, i.e., absence of new MRI lesions, disease relapses, and disability progression, should be aimed for.

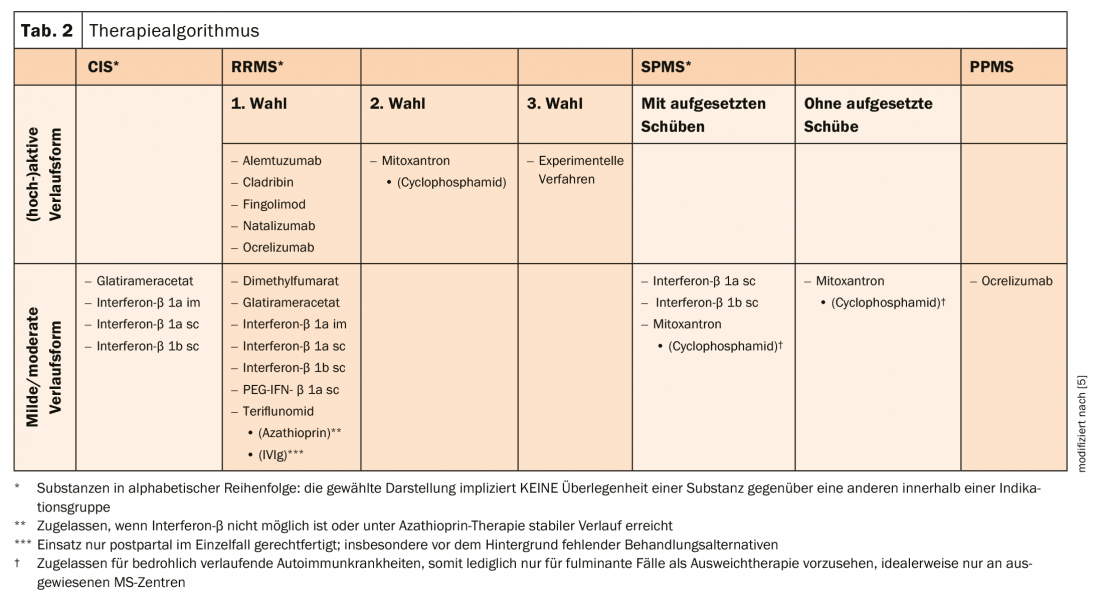

In recent years, several treatment regimens have been developed for different disease courses (Tab. 2). The preparations can be divided into four groups according to their mechanism of action:

- Proliferation inhibition: azathioprine, cladribine, mitoxantrone, teriflunomide.

- Immunomodulation: dimenthyl fumarate, glatiramer acetate, iterferon-β, pegylated iterferon-β, teriflunomide.

- Migration inhibition: fingolimod, natalizumab

- Depletion: alemtuzumab, rituximab/crelizumab

For moderate courses, interferon-β (IFN-β), glatiramer acetate, immunoglobulins, and azathioprine are used as basic therapy for the relapsing-remitting course. These immunomodulatory preparations inhibit damaging and promote protective processes of the immune system. In patients with a (highly) active course (i.e., many, severe relapse events in a short period of time and/or (highly) active MRI) or patients who do not respond adequately to basic immunotherapeutics, escalation therapy medications are used. These include, for example, short-term oral therapeutics such as cladribine tablets, which selectively and periodically target lymphocytes in relapsing-remitting MS. Reducing the lymphocyte count should reduce the frequency of relapses. Another option is to block the sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor using fingolimod, which retains immune cells in the lymph nodes. Monthly infusion therapies with the monoclonal antibody natalizumab also prevent immune cells from migrating into CNS inflammatory sites [6–8].

Literature:

- www.multiplesklerose.ch/das-schweizer-ms-register/

- Ziemssen T, Derfuss T, de Stefano N, et al: Optimizing treatment success in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol 2016; 263: 1053-1065.

- De Stefano N, Airas L, Grigoriadis N, et al: Clinical relevance of brain volume measures in multiple sclerosis. CNS Drugs 2014; 28: 147-156.

- Barro C, Benkert P, Disanto G, et al: Serum neurofilament as a predictor of disease worsening and brain and spinal cord atrophy in multiple sclerosis. Brain 2018; 141(8): 2382-2391

- www.multiple-sklerose.com/medikamente-zur-behandlung/

- www.neurologen-und-psychiater-im-netz.org/neurologie/erkrankungen/multiple-sklerose-ms/therapie

- www.mpg.de/411133/forschungsSchwerpunkt

- DGN/KKNMS: Guideline for diagnosis and therapy of multiple sclerosis

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2020; 18(1): 22-23.