Inflammation of the subcutis is difficult to assess. David Anliker, MD, provides an overview of differentiation and histopathology.

A principle in dermatology and dermatohistopathology is that you can only make a diagnosis if you know what different diseases are possible. Therefore, in the evaluation of panniculitis, I remembered early on that there are 28 different causes of adipositis. In truth, however, it is even more complicated. There is also the problem that certain clinical entities tend to be historically descriptive and have never been properly pathogenetically elucidated.

Differentiate panniculitis according to clinical aspects

Can the different forms of adipositis be distinguished on visual inspection or by palpation?

In some cases, yes. First, a distinction can be made between solitary nodes versus multiple ones. The former would be, for example, traumatic panniculitis, foreign body panniculitis; the latter are more reactive panniculitides such as erythema nodosum or systemic diseases such as sarcoidosis, autoimmune diseases, or infectious panniculitides such as erythema induratum Bazin. Further, diffuse foci are more suggestive of infectious triggers, clearly circumscribed ones of granulomatous foci as in sarcoidosis, fribrosing ones as in deep morphaea. A very hard palpation finding could again be suggestive of deep morphaea, or calcifying panniculitis in CREST syndrome, scleroderma, or as a result of calciphylaxis.

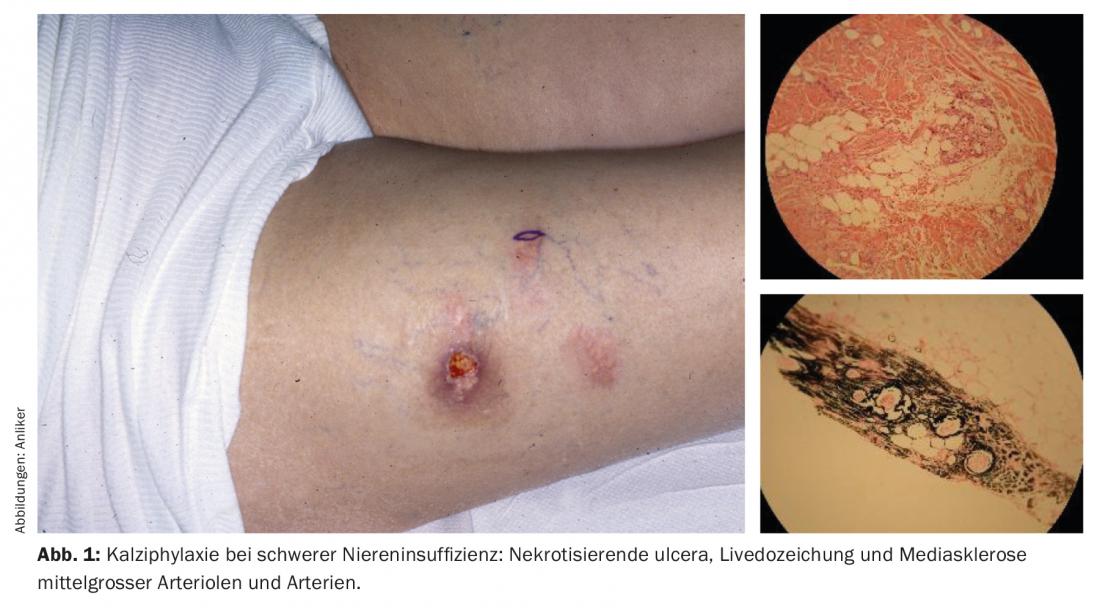

Calciphylaxis occurs in grossly undertreated renal failure and secondary hyperparathyroidism – a serious development leading to ulceration and short survival. At best, this can be favorably influenced by immediate dialysis and dissolution of calcium increments with thioaureosulfate i.v. [1] (Fig. 1).

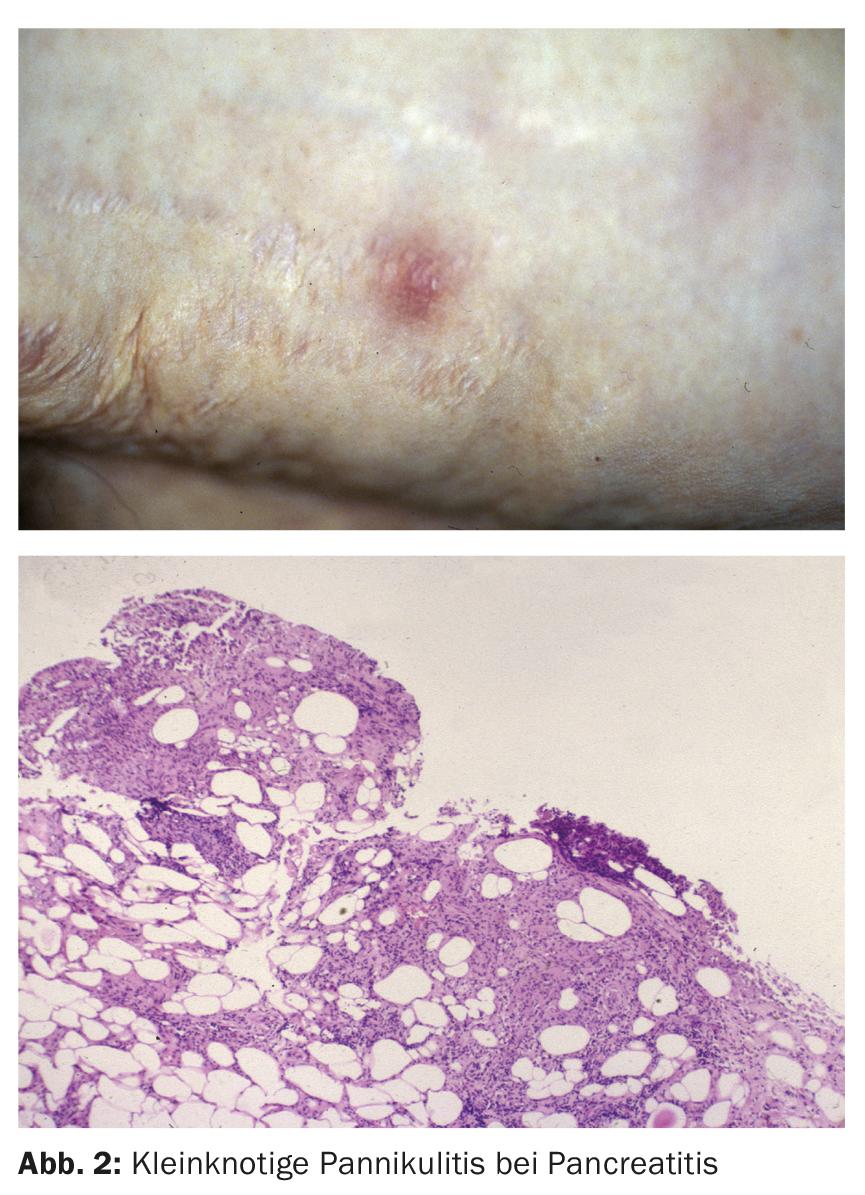

Small-nodule panniculitis would be typical in pancreatic panniculitis (Fig. 2) [2]. But the clinical distinction is not entirely satisfactory. For example, some diseases may have solitary and multiple nodules such as lupus erythematosus profundus, sarcoidosis, and cold panniculitis, so in almost every case, tissue examination by deep biopsy should be resorted to.

Differentiation according to histopathological aspects

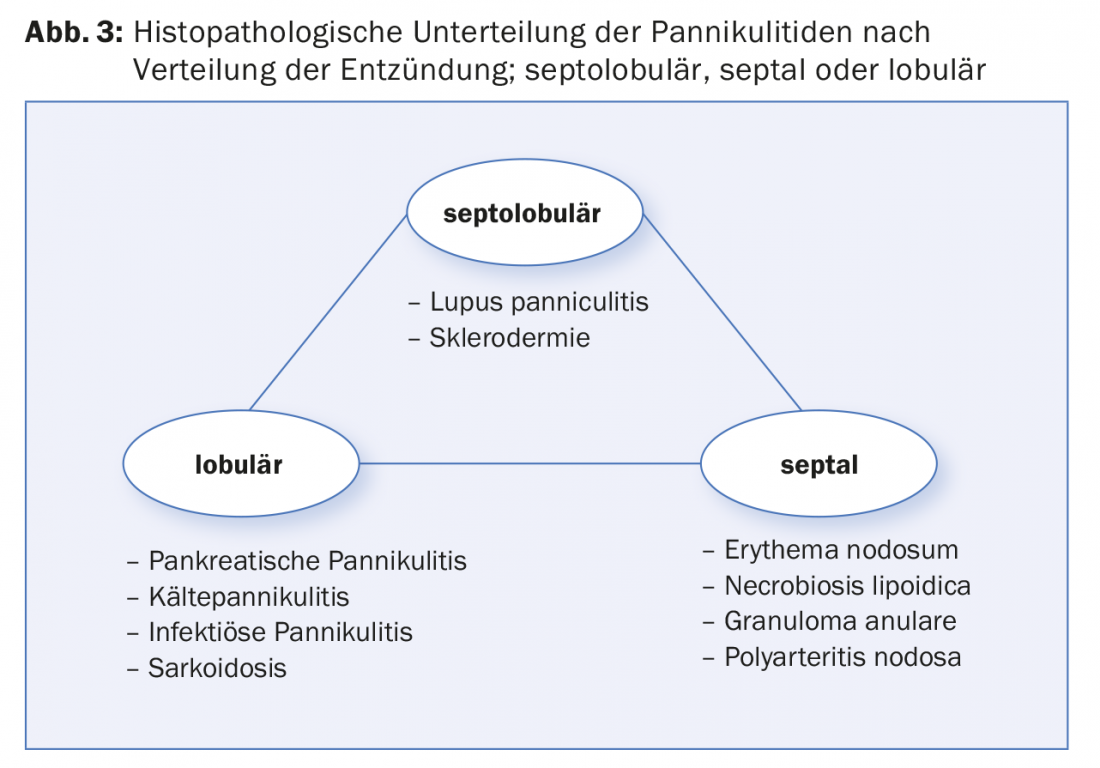

The histopathological differentiation or classification of panniculitis depends on the distribution of the inflammation in the adipose tissue (Fig. 3) . For example, lobular, septolobular (lupus erythemathodes) and septal panniculitis (erythema nodosum) are distinguished. In erythema nodosum, inflammation is found not only subcutaneously but also in the deep to middle dermis – as in some other diagnoses, for example, calciphylaxis, which begins in the deep dermis and in which calcified vessels can also be found in the subcutis. Actually, it is primarily a metabolic disease with typical mediasclerosis.

The second distinction is for the presence of vasculitis. Thus, vasculitic elements of the larger vessels are seen in polyarteritis nodosa, in Crohn’s disease, and small-vessel vasculitis in erythema nodosum leprosum.

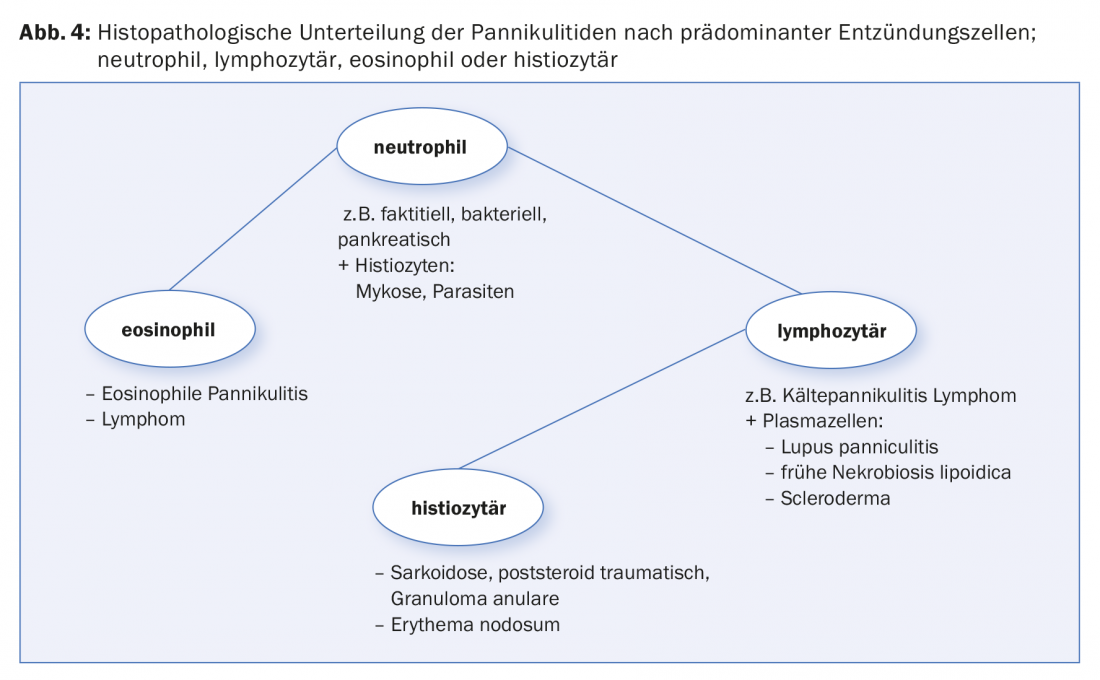

The third differentiation according to histopathological aspects happens on the basis of the different inflammatory cells (Fig. 4), thus, lymphocytic predominance of inflammation is typical of lupus erythematosus (here additionally with plasma cells), histiocytic for erythema nodosum and necrobiosis lipoidica, whereas neutrophil-rich inflammation is indicative of some others such as most infectious panniculitides and pancreatic adipositis.

Lymphoma diagnosis is also challenging in the subcutis; for example, panniculitic T-cell lymphoma shows a lymphocytic infiltrate with lymphoma cells strung like stones around fat lobules and intravascular T-cell lymphoma, which sometimes can only be conclusively assessed by serial biopsies [3].

Erythema nodosum versus nodose erythema

Erythema nodosum is a usually self-limited reactive inflammation that occurs symmetrically and multiply on the dorsal lower legs and is very painful on pressure, at first tenderly erythematous and then progressively intensifying in color and becoming purplish livid. Causes in erythema nodosum and concomitant diseases are: Sarcoidosis, enteritis with shigella, yersinia and salmonella, mycoplasma infections, streptococcal infections and presumed further infections, pregnancy and, as representatives of the neutrophilic dermatoses, also chronic intestinal diseases such as ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease.

Nodular erythema is also found on the upper extremities, is difficult to distinguish histopathologically, but usually lasts longer than self-limited erythema nodosum, which is present for approximately seven weeks. This is more likely to be caused by medications, especially contraceptives. Atypical courses and clinic are also possible in chronic bowel disease. Furthermore, reactive nodular erythema occurs in the treatment of tuberculosis and leprosy, erythema nodosum leprosum. In general, the supposedly antibiotic-induced forms raise the question whether they are not in fact a reaction to the antigen release of the bacteria. Therapeutically, there is no evidence for the use of steroids in erythema nodosum; the clearest evidence is for the efficacy of potassium iodatum, a salt capable of counteracting the inflammatory process. Of course, the infectious, inflammatory triggers should be treated and the medicinal ones omitted.

Panniculitis in internal diseases

Due to pancreatitis, Lyme disease, sarcoidosis, renal insufficiency or alpha-antitrypsin-1 deficiency, panniculitis may occur, which must be specifically searched for either by clinical suspicion (small nodules in pancreatitis, calcification in renal insufficiency) or after a clear diagnosis has been omitted on the part of histopathology.

Panniculitis in autoimmune diseases

Lupus erythematosus (Fig. 5) [4], scleroderma, dermatomyositis may lead to isolated panniculitis (in the form of calcinosis cutis in scleroderma, for example), which may occur with or without other skin manifestations. Whole body inspection, clinical questions (light sensitivity, muscle pain, difficulty swallowing, salivation, etc.) and, if necessary, serologic testing for autoantibodies are important. Shulman’s syndrome, which is actually even deeper than the subcutis and is characterized by painful deep swellings and only a little erythema, offers a special feature; this is an eosinophilic fasciitis that belongs to scleroderma and historically was also triggered by L-tryptophan in the past.

The erythema induratum Bazin

Erythema induratum Bazin is actually the counterpart of erythema nodosum in that it is strictly localized to the calf or calves (Fig. 6), but also appears painful with granulomatous foci that are also deeper and prone to ulceration. It raises some questions. First, erythema bazin is considered an association with tuberculosis (TB), which must be sought in every case. However, even after the treatment of TB. the disease often persists independently and occurs at all even without associated TB. on.

Other subcutaneously located diseases include deep granuloma anulare, deep infections such as deep mycosis and deep nocardiosis, and a host of other bacterial and parasitic pathogens, especially in the tropics and in immunosuppression.

Historically described forms of panniculitis

Some described forms of panniculitis are probably multiple descriptions, i.e., duplications of the same disease and more reactive in nature: for example, lipogranulomatosis subcutanea Rothman Makai, which is considered idiopathic, and panniculitis febrilis non suppurativa Pfeiffer-Weber-Christian, which often occur solitarily and may be autoinflammatory or reactive as in ulcerative colitis, for example [5] (Fig. 7).

Cold panniculitis

Is it physical panniculitis, cryoblogulin-associated panniculitis, or lupus erythematosus-associated panniculitis? Can this be distinguished? This is most likely to be possible with a deep tissue biopsy, which should show livedovasculitis in cryoglobulinaemia, septolobular lymphocytic inflammation in lupus erythematosus, and necrosis in adipose tissue in physical cold panniculitis.

Not all panniculitis is the same – the differential diagnosis

By definition, panniculitis is an inflammation of adipose tissue and includes all of the entities described here; panniculite, on the other hand, is a fat distribution disorder usually found in women that results from oversized fat lobules that are less degradable and therefore lead to nodule formation. This is genetically predisposed, but also dependent on weight fluctuations. Thus, when weight is lost, it tends to get worse and more humpy, and the only helpful acts are physical actions such as water, cold, mechanical friction, massages, etc.

Traumatic and foreign body panniculitis

Posttraumatically, there is inflammation and usually atrophy and dimpling of adipose tissue, such as calf-localized ligamentous atrophy; however, this is also possible after steroid infiltration, called steroid atrophy, but also after other injections. Foreign bodies such as silicone, hyaluron or kerosene, depending on the reaction situation, lead to a foreign body reaction with granuloma formation; the latter to the so-called paraffinoma, which has a characteristic perforated “Swiss cheese” pattern in the histopathology.

Therapy is not straightforward and depends on the underlying pathology or concomitant disease, or both. Topical treatment is limited because many agents do not diffuse into the subcutis. An exception is tacrolimus ointment and tazarotene gel, which penetrates relatively well. In addition, moist compresses can be used for cooling and occlusive treatment with ointments supports the migration through the epidermis and dermis (clobetasol diproprionate ointment, for example). Systemic therapy has great importance, be it steroids, retinoids, antibiotics, antimalarials, immunosuppressants or other substances.

Conclusion

Causes of adipositis are many; diagnosis is difficult because clinical differentiation is not evident due to the depth of the disorder and histopathology often does not lead to a characteristic picture, but must take place precisely because of the risk of infection and tumors. Thus, the medical history and concomitant internal diseases must contribute to the diagnosis, traumatic events must be inquired about, the use of medications, local injections, chronic diseases, and the skin must be examined to find evidence of a deep form of a usually superficial disease or infection.

Take-Home Messages

- Subcutaneous inflammation is difficult to assess because little can be seen on the surface and little is clear to palpate.

- In addition to distinguishing clinical features, such as size of nodules, retractions, hemorrhages, there are histopathological features.

- Histopathology distinguishes between septal, septolobular, and lobular panniculitis, as well as the composition of the inflammatory cells.

- The differential diagnosis includes tumorous causes of an infectious, autoimmune, traumatic, autoinflammatory, and reactive nature.

Literature:

- Hafner J, et al: Uremic small-artery disease with medial calcification and intimal hyperplasia (so-called calciphylaxis): a complication of chronic renal failure and benefit from parathyroidectomy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995 Dec; 33(6): 954-962.

- Menzies S, et al: Pancreatic panniculitis preceding acute pancreatitis and subsequent detection of an intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm: A case report. JAAD Case Rep. 2016 Jun 24; 2(3): 244-246.

- Hundsberger T, Anliker MD, et al: Intravascular lymphoma mimicking cerebral stroke: report of two cases. Case Rep Neurol. 2011 Sep; 3(3): 278-283.

- Böhm I, et al: ANCA-positive lupus erythematosus profundus. Successful therapy with low dose dapsone]. Dermatologist. 1998 May; 49(5): 403-407.

- Jaeger T, Anliker MD, et al: Pfeiffer-Weber-Christian syndrome (panniculitis nodularis nonsuppurativa febrilis) associated with ulcerative colitis. Poster SGDV Annual Meeting 2011 Sept.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2017; 27(3): 20-24