It is undisputed that smoking is harmful and among the most important causes of premature morbidity and mortality. Because of the serious health consequences, smoking cessation counseling is important and one of the most cost-effective health care interventions. Since the Federal Court decision in July 2011, smoking has also been considered a disease in Switzerland. In the course of this, varenicline was added to the list of specialties as a stop-smoking drug this year and is reimbursed by health insurers under certain conditions. With nicotine replacement products and bupropion, two other effective groups of medications are also available to support smoking cessation. This article is aimed at practicing physicians who are confronted with the problem of smoking on a daily basis.

Smoking is a mass phenomenon. According to figures from the Federal Office of Public Health, the prevalence of smokers in Switzerland is about 25% (www.bag.admin.ch) with about 18% regular smokers and 7% occasional smokers. This proportion has remained more or less stable since 2008. It is particularly alarming that the highest proportion of smokers, 35%, is in the 20-24 age group.

Health consequences of smoking

In addition to widely known complications such as lung cancer, cancers of the oropharyngeal tract, and chronic diseases of the cardiovascular system and lungs, numerous other diseases are associated with smoking. For example, active smokers have a two- to sevenfold increased risk of myocardial infarction – with the negative impact of smoking being greatest in younger people [1]. For example, the risk of lung cancer increases 36-fold in female smokers if they smoke more than 20 cigarettes per day [2].

According to the WHO, smoking is the single most important preventable cause of premature death worldwide, in both low- and high-income countries. It is not the highly addictive nicotine that is the main health hazard, but the approximately 4000 detectable hazardous substances in tobacco smoke.

In summary, it is consistently shown by several large epidemiological studies that in the age group up to 35 years, the life expectancy of smokers is shortened by about ten years [3, 4]. The health risk from tobacco use is dose-dependent and even a small consumption of 1-5 cigarettes per day is significantly harmful to health [2].

Advantages of quitting smoking

Compared with other health care prevention interventions, nicotine abstinence is associated with tremendous risk reduction at any age. If smoking is stopped by age 34, life expectancy remains comparable to that of nonsmokers; even into old age, life expectancy is significantly extended [2,3,5]. For numerous diseases such as coronary heart disease or COPD, it has been proven that stopping smoking is associated with a significant improvement in prognosis. In this context, smoking cessation is extremely cost-effective [6].

Increasing attention is being focused not only on smoking but also on the increased health risk posed by passive smoking. Here, it is estimated that approximately 80,000 deaths were attributable to secondhand smoke in Europe in 2002, of which approximately 32,000 were due to cardiovascular disease [7]. In this context, data have already been published showing that, for example, shortly after the introduction of a smoking ban in public places, acute cardiovascular events can be significantly reduced [8].

Why do smokers smoke?

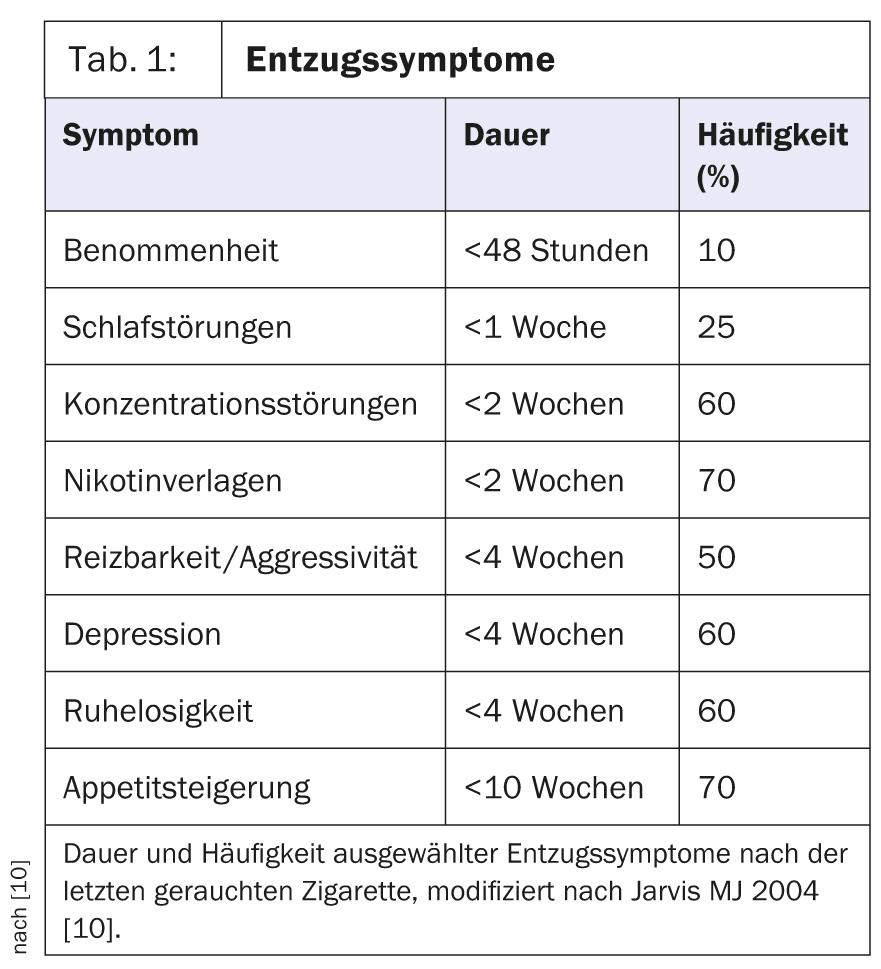

The reasons for starting smoking may be many, but the reason for maintaining smoking is largely due to nicotine dependence. Nicotine binds to nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the so-called reward center (nucleus accumbens of the mesolimbic system) and leads to positive effects such as performance enhancement, mood elevation, calming, and well-being via dopamine release [9]. Permanent stimulation of the receptors leads to the development of tolerance, while a lack of stimulation leads to withdrawal symptoms. These include, but are not limited to, impaired concentration, dizziness, sleep disturbances, increased irritability, increased appetite, and strong cravings for nicotine.

Most withdrawal symptoms diminish over the first month after discontinuation of the stimulus , but in particular the strong craving for nicotine and the increased feeling of hunger may persist for months (Table 1) [10].

A large proportion of smokers have already made at least one attempt to stop smoking, but in the vast majority of cases without seeking the help of a doctor or specialist. In principle, about every second smoker in Switzerland has the intention to quit smoking (www.tabak monitoring.ch), with a success rate of less than 10% for unguided quit attempts [11]. This success rate can be significantly increased by professional support.

Practical procedure

A prerequisite for successful smoking cessation is that patients are motivated to do so. Over a longer period of time, it is usually the case that smokers give little thought to the health consequences of their habit and that the positive aspects of smoking clearly outweigh any concerns. In this situation, the willingness to try to stop smoking is low and not promising.

Our task as treating physicians in this situation is to inform smokers individually about the negative aspects of smoking and to urge them to stop smoking – this in a motivating and non-judgmental discussion situation in which the smoker’s ambivalence is to be worked out.

Information about smoking cessation benefits should be tailored as much as possible to the patient’s preexisting conditions or specific situation. Stereotypical argumentation on the part of the physician should be avoided at all costs, because it usually leads to resistance on the part of the smoker at this stage. The patient’s individual motivation to stop smoking should be ascertained (health concern, financial incentive, role model for children and grandchildren) and supported on that basis.

The goal is to get our patients to change their thinking, to consider quitting smoking and ultimately to want to do so. This process of rethinking can take years.

Once the decision to quit smoking has been made, it is essential that support is offered in this regard: either through the patient’s own consultation or by referral to a specialist service (a list of smoking advice centers is available, for example, through Hospital Quit Support, the Cancer League or the National Stop Smoking Line).

Stop smoking counseling

Optimally, smoking cessation counseling is provided at three levels:

- Patients should be informed about nicotine dependence, withdrawal symptoms, and relapse risks. It is important to explore past quit attempts in detail and to help the smoker gain confidence to try again and to ease fears of failure.

- Behavioral therapy counseling should be provided to patients. If ambivalences are present, they must be named and discussed. When a stop date is set with the patient, strategies for various situations that may increase the risk of relapse should be discussed with the patient. It is important that the smoker is involved in this and retains choices. It has proven effective to remove all nicotine products from the personal environment on the stop date, to announce the stop date to friends and family and to ask for their support. Smokers should be made aware that relapse is particularly common associated with alcohol consumption in the company of smokers [12].

- In addition, every smoker should be informed about the available medication options. These consist of three effective drug groups (NET, varenicline, bupropion).

Nicotine replacement therapy (NET)

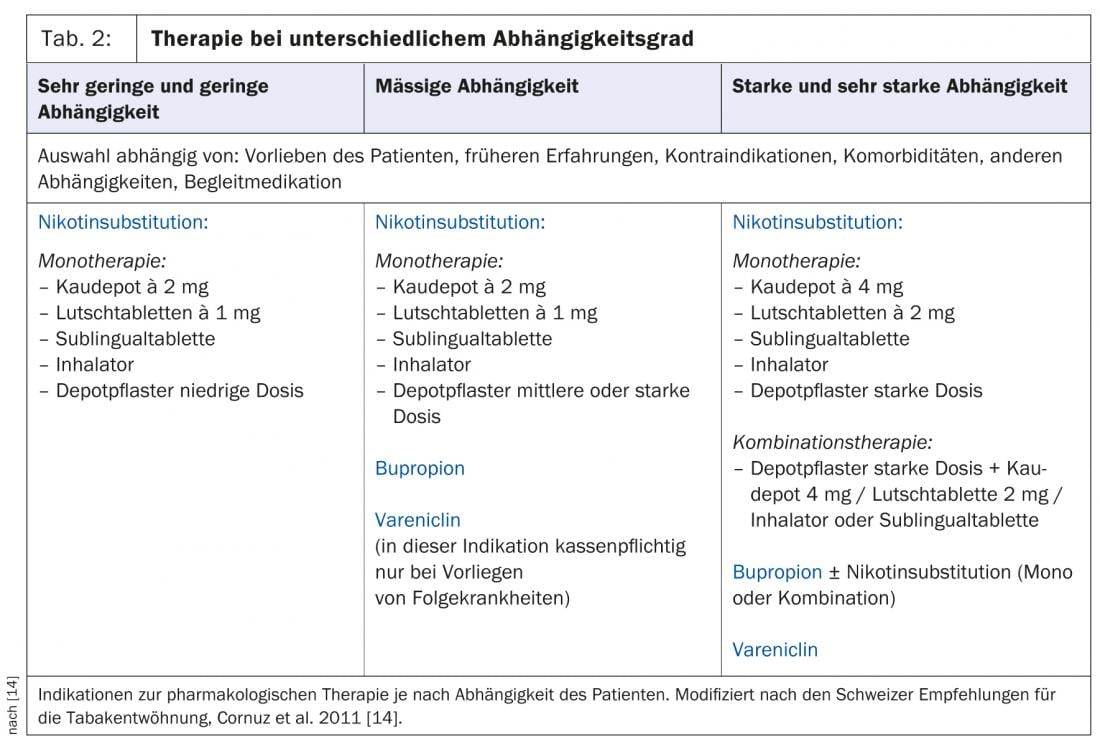

Nicotine replacement products are available in various delivery forms: Nicotine patches, chewables, lozenges and inhalers. The choice of product depends on the patient’s preference and dependence (Table 2).

To increase the effectiveness of NET, it is useful to combine continuous nicotine delivery via transdermal patch with a short-acting route of administration. The dosage must be chosen sufficiently high, the product must be properly applied by the patient and used long enough. Special attention must be paid to this in counseling, because the most common causes of relapse under NET are too low a dosage or too short a duration of therapy.

The duration of therapy should be 8-12 weeks, the effectiveness of an application beyond this time is not proven [13]. For pathophysiological reasons, it makes sense to gradually reduce the dose towards the end of therapy. An algorithm on the use of NET that has been adapted for Switzerland and is very suitable for everyday use can be found in the 2011 revised Swiss recommendations for tobacco cessation (available at www.frei-von-tabak.ch) [14]. A particular advantage of NET is that there are no absolute contraindications to therapy.

Varenicline

Varenicline is a partial agonist at the neuronal α4β2-acetylcholine receptor, thereby reducing craving and withdrawal symptoms during smoking cessation. In addition, smoking cigarettes fails to provide satisfaction because the additional nicotine does not lead to further receptor activation. This favors behavioral change through deconditioning.

Varenicline is dosed gradually over the first week. From the second week, the full dose of 2×1 mg/d is used. Smoking cessation should be planned within the second week of therapy according to the professional information, which means that the patient can continue to follow his habit during the first days of therapy. However, there is preliminary evidence that a longer period of “pre-loading” of up to five weeks may result in higher abstinence rates [15].

The use of varenicline is recommended for three months and may be extended up to a total of six months. Side effects that may occur with varenicline therapy include nausea, dizziness, and nightmares.

Varenicline is not approved for pregnant or breastfeeding women, and severe renal insufficiency is also considered a contraindication. Concerns for use have been in patients with psychiatric and cardiac conditions. However, a recently published randomized trial in patients with stable depression as well as a meta-analysis of varenicline randomized trials failed to demonstrate a significant safety risk for psychiatric complications [16, 17]. The same is true for patients with pre-existing cardiovascular conditions – again, a recent meta-analysis failed to substantiate safety concerns [18].

A special feature of varenicline is that it has been approved for use by health insurers under certain conditions since July 2013. Thus, 12 weeks of smoking cessation per 18 months is paid by the compulsory basic health insurance if the following criteria are met:

- The smoker is >18 years, motivated to stop smoking and receives professional advice and support.

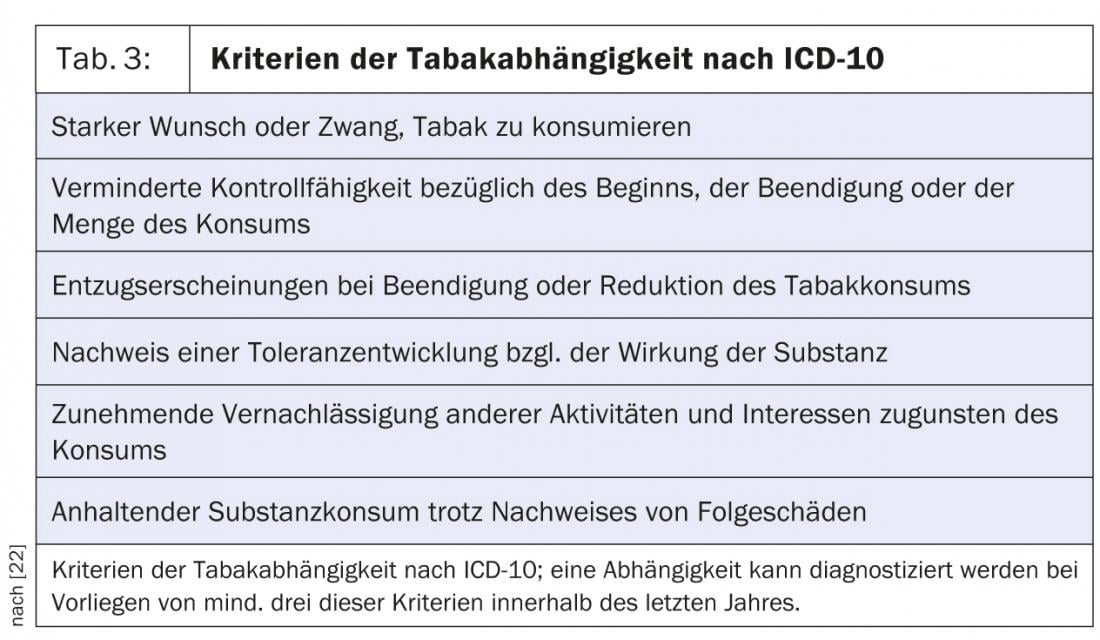

- There is a tobacco dependence according to ICD 10 (Tab. 3) or nicotine dependence according to DSM-IV.

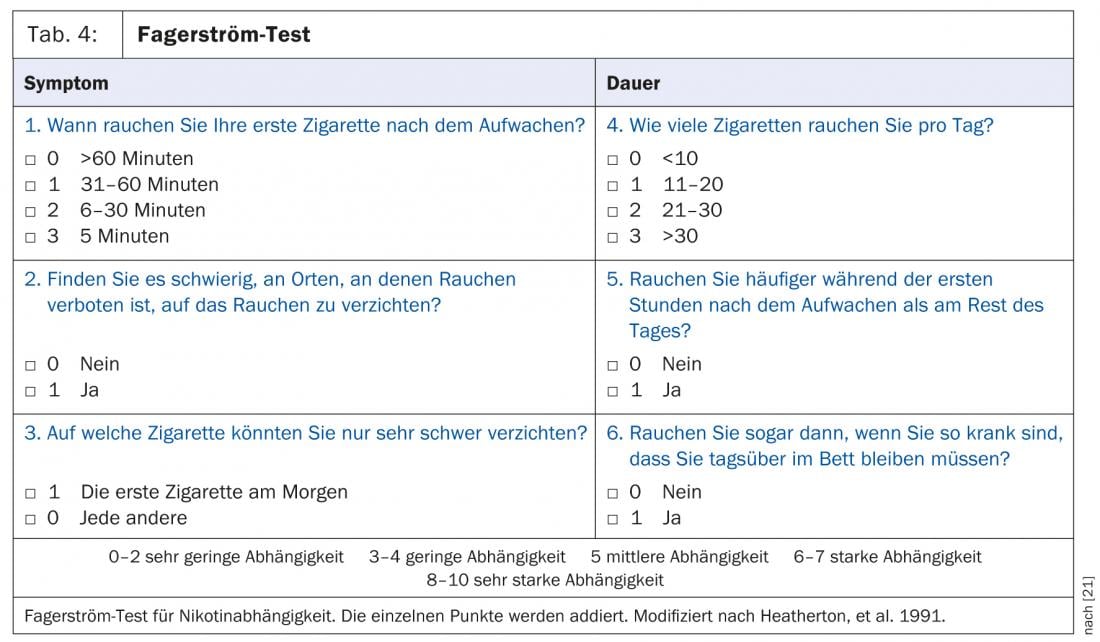

- There is secondary tobacco disease or severe dependence according to the Fagerström test (≥6 points) (Table 4).

Bupropion

Bupropion, an atypical antidepressant, can also be used supportively in smoking cessation. The effect is via reuptake inhibition of dopamine and norepinephrine.

The initial dose is 150 mg/d for six days and 2×150 mg/d thereafter, with a dosing interval of at least eight hours. Smoking cessation is determined together with the patient between day 8 and 14. Therapy usually lasts eight weeks, but this can be extended to 6-12 months if withdrawal symptoms are severe.

The contraindications must be observed. These include epilepsy, anorexia or bulimia, central nervous system tumors, and severe liver cirrhosis. In patients with hepatic or renal impairment, dose reduction is recommended at most.

Insomnia is a very common side effect of this drug. This can be counteracted by not taking the evening dose immediately before bedtime (provided there is at least eight hours between individual doses).

How effective are the drugs?

In terms of drug efficacy, according to the current review of studies, varenicline is the most effective agent for smoking cessation, along with combined NET. A 2013 Cochrane analysis found an odds ratio for sustained smoking cessation over six months of 2.88 for varenicline compared with placebo. For comparison, the odds ratio for NET was 1.84 and for bupropion 1.82.

Varenicline also performed better in a head-to-head comparison than single NET and than bupropion, and comparable efficacy existed with combined NET [19].

In addition to the smoker’s personal preference, the severity of nicotine dependence is the decisive factor in the individual selection of medication. The patient’s dependence can be elicited using the Fagerström questionnaire (Table 4) . Depending on the score achieved, a distinction can be made in five levels from very low to very high dependence and the therapy planned accordingly (Table 2). For all drugs, the necessary dose and duration must be adhered to in order to achieve an optimal effect.

Aftercare

Patients should be offered as much support as possible in the immediate post-smoking phase. As a guide, the Swiss guidelines for tobacco cessation recommend follow-up visits after 1, 2, 4, and 8 weeks.

For patients who have quit smoking during hospitalization, treatment in the outpatient setting must continue seamlessly, as a sustained effect is only achieved if care is continued for at least four weeks [20]. During these consultations, past experience, withdrawal symptoms, and medication tolerance should be discussed.

Even with optimal care, it is important to realize that a large proportion of initially abstinent smokers will relapse within the first year. In these cases, the circumstances that led to the relapse should be discussed. Consideration may be given to repeat or alternative drug treatment or to prolonging drug treatment. Patients should be encouraged to view relapse as an experience from which they can benefit the next time they attempt to wean. Motivation should be aimed at a new attempt.

CONCLUSION FOR PRACTICE

- Smoking cessation is one of the most cost-effective interventions in our health care system.

- For physicians who provide smoking cessation counseling in the office, it is optimally provided at three levels:

- Informing the patient about nicotine dependence, withdrawal symptoms, and relapse risks.

- Behavioral therapy counseling with regular, close-meshed follow-ups and accompaniment on the path to weaning

- Sufficiently long and optimally dosed drug support.

Literature:

- Teo KK, et al: Tobacco use and risk of myocardial infarction in 52 countries in the INTERHEART study: a case-control study. Lancet 2006; 368(9536) :647-58. Epub 2006/08/22.

- Pirie K, et al: Million Women Study C. The 21st century hazards of smoking and benefits of stopping: a prospective study of one million women in the UK. Lancet 2013; 381(9861): 133-41. epub 2012/10/31.

- Doll R, et al: Mortality in relation to smoking: 50 years’ observations on male British doctors BMJ 2004; 328(7455): 1519. Epub 2004/06/24.

- Jha P, et al: 21st-century hazards of smoking and benefits of cessation in the United States. The New England journal of medicine 2013; 368(4): 341-50. epub 2013/01/25.

- Gellert C, et al: Smoking and all-cause mortality in older people: systematic review and meta-analysis. Archives of internal medicine 2012; 172(11): 837-44. epub 2012/06/13.

- Hoogendoorn M, et al: Long-term effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of smoking cessation interventions in patients with COPD. Thorax 2010; 65(8): 711-8. epub 2010/08/06.

- Nichols M, et al: European cardiovascular disease statistics 2012 edition. ed. 125 pages p.

- Pell JP, et al: Smoke-free legislation and hospitalizations for acute coronary syndrome. The New England journal of medicine 2008; 359(5): 482-91. epub 2008/08/02.

- Benowitz NL: Nicotine addiction. The New England journal of medicine 2010; 362(24): 2295-303. Epub 2010/06/18.

- Jarvis MJ: Why people smoke. BMJ 2004; 328(7434): 277-9. Epub 2004/01/31.

- Rigotti NA: Clinical practice. Treatment of tobacco use and dependence. The New England journal of medicine 2002; 346(7): 506-12. Epub 2002/02/15.

- Tonstad S: Smoking cessation: how to advise the patient. Heart 2009; 95(19): 1635-40. Epub 2009/09/16.

- Schnoll RA, et al: Effectiveness of extended-duration transdermal nicotine therapy: a randomized trial. Annals of internal medicine 2010; 152(3): 144-51. epub 2010/02/04.

- Cornuz J, et al: Tobacco cessation: update 2011. part 1. Switzerland Med Forum 2011; 11(9): 156-9.

- Hajek P, et al: Use of varenicline for 4 weeks before quitting smoking: decrease in ad lib smoking and increase in smoking cessation rates. Archives of internal medicine 2011; 171(8): 770-7. epub 2011/04/27.

- Anthenelli RM, et al: Effects of varenicline on smoking cessation in adults with stably treated current or past major depression: a randomized trial. Annals of internal medicine 2013; 159(6): 390-400. epub 2013/09/18.

- Gibbons RD, Mann JJ: Varenicline, Smoking Cessation, and Neuropsychiatric Adverse Events. The American journal of psychiatry 2013. Epub 2013/09/14.

- Ware JH, et al: Cardiovascular safety of varenicline: patient-level meta-analysis of randomized, blinded, placebo-controlled trials. American journal of therapeutics 2013; 20(3): 235-46. epub 2013/04/26.

- Cahill K, et al: Pharmacological interventions for smoking cessation: an overview and network meta-analysis. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews 2013; 5: CD009329. Epub 2013/06/04.

- Rigotti NA, et al: Smoking cessation interventions for hospitalized smokers: a systematic review. Archives of internal medicine 2008; 168(18): 1950-60. epub 2008/10/15.

- Heatherton TF, et al: The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence: a revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. British journal of addiction 1991; 86(9): 1119-27. epub 1991/09/01.

- Dilling H: World Health Organization. International Classification of Mental Disorders ICD-10 Chapter V (F) diagnostic criteria for research and practice. 5th, èuberarb. ed. according to ICD-10-GM 2011 ed. Bern: Huber 2011; 253

.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2013; 8(11): 22-27