In elderly and very old patients with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases, multimorbidity and polypharmacy in particular require careful consideration with regard to possible interaction effects.

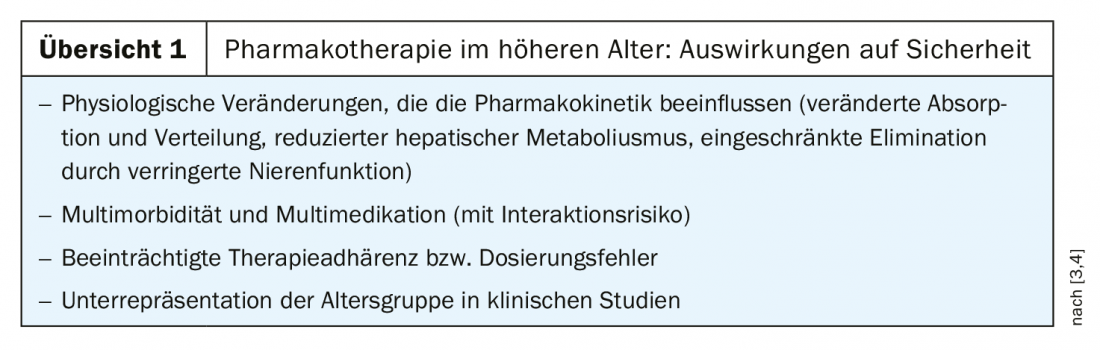

The prevalence of chronic inflammatory rheumatic diseases with initial manifestation in later adulthood is increasing due to demographic change with an increase in average life expectancy. Adequate treatment of gerontorheumatologic patients should be age-adapted, patient-centered, and multidimensional. Chronic inflammatory rheumatic diseases in older age are characterized, among other things, by certain age-related physiological changes that influence pharmacokinetics and are important for the safety of drug therapies (review 1).

Therefore, individual risk assessment prior to antirheumatic therapy is critical. All pharmacokinetic phases (absorption, distribution, biotransformation, elimination) are affected by age-related changes in conditions. With regard to phase elimination, renal processes in particular are subject to age-related modifications, explains Prof. Werner Mayet, MD, specialist in internal medicine and gastroenterology, Nordwestkrankenhaus Sanderbusch in Sande (D). Appropriate consideration of altered renal elimination and increased risk of renal comorbidity is extremely important (caveat: administration of predominantly renally eliminated drugs).

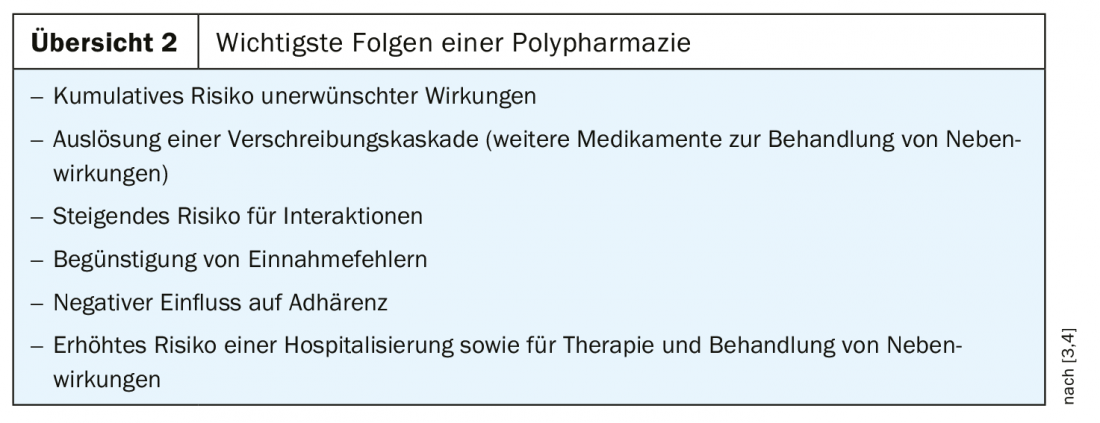

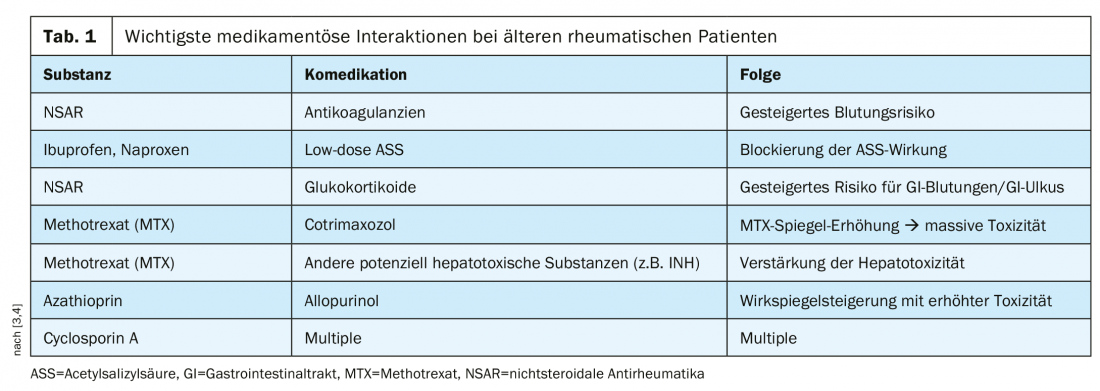

Multimedication is common in elderly patients in the context of multimorbidity, and polypharmacy is not uncommon (criterion: regular ≥5 medications daily), which is associated with certain risks (overview 2). The most important drug interactions with special relevance for the elderly rheumatic patient are summarized in Table 1 .

Adapted therapy strategy

“Disease Modifying AntiRheumatic Drugs” (DMARDs) are substances that are effective beyond symptom relief and modify the course of the disease. Biological and synthetic DMARDs are among the basic medications for rheumatoid arthritis. Combining multiple basic therapeutics is risky in older rheumatoid arthritis patients, so transitioning to biologics is often safer. In addition, according to Prof. Mayet, the following substance-related peculiarities must be taken into account in gerontorheumatological patients:

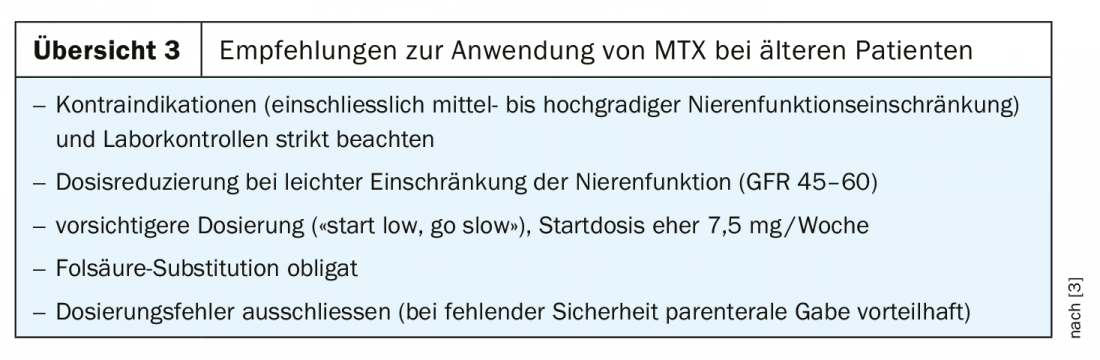

- Non-biologic DMARDs: sulfasalazine: if mild renal impairment is present, dose adjustment is recommended; GFR <50 is considered a contraindication. Methotrexate (MTX) (review 3): comparably effective as in younger patients, discontinuation rate increased in older patients; GFR <50 is considered a contraindication. Leflunomide: largely independent of renal function, good alternative to MTX; risk of desiccosis with diarrhea; risk of blood pressure increase.

- Biological DMARDs (biologics/biosimilars): the most empirical data are available on TNF-alpha inhibitors: response rates are comparable to those of younger patients, infection rates are somewhat increased.

- Steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (glucocorticosteroids): have good efficacy also in the elderly in terms of inhibition of inflammation and pain and do not play a significant role in terms of renal function. Adverse drug reactions are dose-dependent; in elderly patients, even low-dose regular use can significantly increase the risk of infection. With regard to general side effect risks of systemic glucocorticoids, the following measures are recommended: Bone density measurement before starting therapy, osteoporosis prophylaxis, opthalmological control (cataract/glaucoma).

Age-correlated prevalence increase

Prof. Dr. med. Rieke Alten, Chief Physician Internal Medicine II of the Schlosspark-Klinik Berlin (D), addressed in her presentation the chronic-inflammatory rheumatic disease patterns that occur more frequently with increasing age [1].

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA): In late-onset RA (LORA), the initial manifestation occurs at the age of >60-65 years, and in EARLY-onset RA (EORA) below that age [2]. As the average age of the RA patient population continues to rise, the relevance of LORA increases in the future. About one-third of all RA patients are over 60 years old. In the LORA patient population, the risk of cardiovascular and infectious disease and comorbidities is higher than in EORA. The therapy of LORA has changed: Long-term glucocorticoid therapy has been displaced by age-adapted baseline therapy with DMARDs. Currently, methotrexate (MTX) is considered the gold standard in the treatment of EORA and LORA. The data base on the efficacy of conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in elderly patients is small, but reduced efficacy is not yet known, explains Prof. Alten. Despite widespread use, especially in elderly patients, there is little information in the literature on initial dosage, treatment duration, reduction strategies. The rule of thumb is to use as low a dose and for as short a time as possible, especially in the elderly fragile patient. MTX in combination with etanercept, infliximab, adalimumab, abatacept, tocilizumab can arrest clinical and radiological progression analogous to EORA. Comparable efficacy data exist regarding the combination of MTX with new oral Janus kinase inhibitors tofacitinib and baricitinib. For EORA and LORA, high disease activity is an independent risk factor for mortality, cardiovascular disease, and infection. He said that therapy with DMARDs, which reduces disease activity, is useful in EORA and LORA.

Polymyalgica Rheumatica (PMR): This disease occurs almost exclusively in the over-50 age group. After RA, it is the second most common inflammatory rheumatic disease in older age. No specific diagnostic tests exist; diagnosis is made by differential exclusion. If PMR is diagnosed, glucocorticoids should be used first. In case of high risk of relapse or high risk of side effects, switch to MTX may be made.

Axial spondyloarthritis (axSpA): Only 5% of SpA patients are over 50 years of age at initial presentation. Particular characteristics of axSpA in the elderly include involvement of the cervical spine; peripheral joint involvement of the upper and lower extremities; and mixed forms with axial and peripheral involvement.

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA): The manifestation of PsA usually occurs about ten years after the diagnosis of psoriasis. Particular characteristics of PsA in older individuals are an onset with more severe symptoms and a much more destructive course. Fatigue and comorbidities are more common, and pain levels and inflammatory markers are higher, while dactylitis and nail involvement are less common. Like smoking and age, PsA is an independent risk factor for subclinical atherosclerosis [3].

In conclusion, adequate safety of pharmacotherapeutic treatment in elderly and very old patients with rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases plays a central role, and therapy should always take into account individual risk factors.

Literature:

- DGIM: Prof. Dr. med. Rieke Alten, Chief Physician Internal Medicine II, Schlosspark-Klinik Berlin (D), Slide presentation: Gerontorheumatology, 125. Congress of the German Society of Internal Medicine, Wiesbaden, May 4, 2019.

- Krams T, et al: Effect of age at rheumatoid arthritis onset on clinical, radiographic, and functional outcomes: The ESPOIR cohort. Joint Bone Spine 2016; http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jbspin.2015.09.010.

- DGIM: Werner Mayet, MD, Specialist in Internal Medicine and Gastroenterology, Nordwestkrankenhaus Sanderbusch in Sande, slide presentation: Gerontorheumatology, 125. Congress of the German Society of Internal Medicine, Wiesbaden, May 4, 2019.

- Krüger K, Strangfeld A, Kneitz C: Safety of rheumatoid therapy in old age. Journal of Rheumatology 2014; 3: www.springermedizin.de/sicherheit-der-rheumatherapie-im-alter/8387360.

FAMILY PRACTICE 2019; 14(8): 38-39

InFo PAIN & GERIATURE 2019; 1(1): 30-31.