In recent years, the prognosis of metastatic HER2-positive breast carcinoma has been significantly improved by the development of new agents such as the antibody-drug conjugate (ADC) trastuzumab-deruxtecan and the HER2-targeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor tucatinib. So much so, that a curative treatment approach was even presented at the 2020 San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium. Nevertheless, especially unexplained resistance mechanisms, CNS metastases and the choice of the right therapy sequence in advanced stages still pose major challenges in clinical practice today.

A look at the overall survival of patients with metastatic HER2-positive breast cancer proves that a lot has happened in the last 20 years. While the median overall survival (OS) was just over 20 months in 2001, it was over 40 months in 2019 with an 8-year survival of 37% [1]. The introduction of HER2-targeted therapy with trastuzumab, pertuzumab and trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1) was certainly decisive for this development. But better patient selection and earlier detection are also important factors that have helped improve prognosis, according to Nancy Lin.

Current development: Revolution in the third and fourth lines

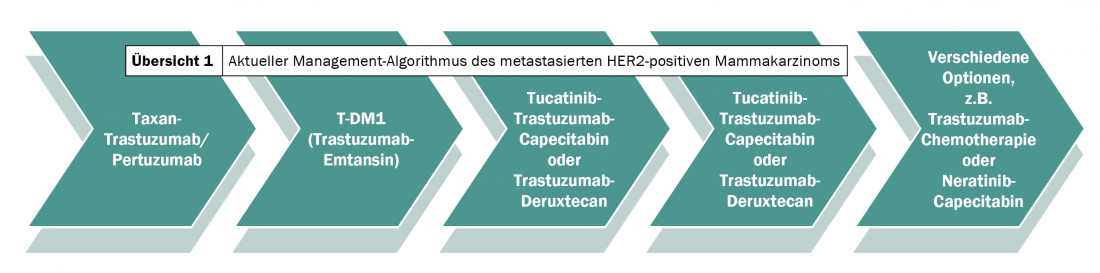

In addition to trastuzumab, pertuzumab and T-DM1, other innovative HER2-targeted agents have been introduced in the recent past, which are currently mainly used in third- and fourth-line therapy. Thus, in the last two years, a standard of care has also been established for patients with disease progression (Overview 1).

Where various trastuzumab or lapatinib-chemotherapy combinations were still used in 2018 after T-DM1 treatment failure – often on the off chance – more promising options exist today. Depending on intracranial involvement, comorbidities, and preferences, either trastuzumab-deruxtecan or tucatinib is applied first. After first-line therapy with trastuzumab/pertuzumab combined with taxane chemotherapy, second-line treatment with T-DM1 follows as before. If this fails, the new active ingredients are used alternately. The bottom line is that the standard of care has been expanded from two to four lines over the last two years – with lasting effects on clinical outcomes.

At the center of this positive development is research into trastuzumab-deruxtecan and tucatinib. Trastuzumab-deruxtecan is a three-component antibody-drug conjugate (ADC). An extremely potent, membrane-permeable topoisomerase I inhibitor is coupled by a cleavable linker to a monoclonal antibody with the same amino acid sequence as trastuzumab. The half-life of the intact conjugate is six days. Clinical trials to date have shown an objective response rate of approximately 60% in patients pretreated with T-DM1, but no randomized trials exist to date [2].

The use of tucatinib, on the other hand, is under scrutiny in the randomized-controlled HER2CLIMB trial [3]. The addition of the HER2-selective tyrosine kinase inhibitor to therapy with trastuzumab and capecitabine increased median progression-free survival from 5.6 to 7.8 months and median overall survival from 17.4 to 21.9 months. Although long-term data are lacking, these initial results are promising in view of the extremely poor prognosis after progression under T-DM1.

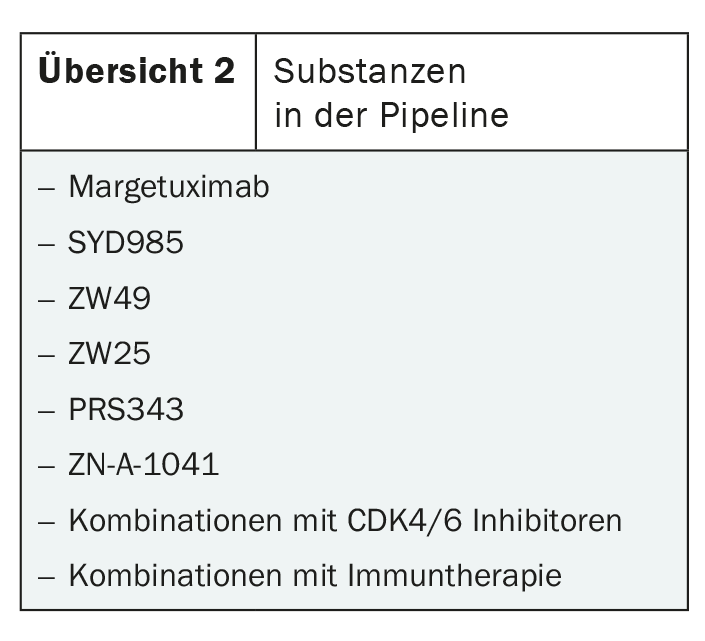

In addition to trastuzumab-deruxtecan and tucatinib, there are numerous other substances in the pipeline. These range from the HER2-targeted monoclonal antibody margetuximab to antibody-toxin conjugates such as SYD985 and combinations with immunotherapy or CDK4/6 inhibitors (overview 2) . Whether these approaches will shape the treatment of metastatic HER2-positive breast cancer in the future remains to be seen. In any case, there is no lack of innovation.

CNS metastasis in focus

In her presentation, Nancy Lin emphasized the importance of CNS metastasis several times. This is because even though the prognosis of metastatic HER2-positive breast cancer has improved significantly, the numbers of brain metastases have not declined and have not been reduced by adjuvant HER2-targeted therapies to date. Although the introduction of T-DM1 has curbed the overall recurrence rate, it has had no impact on CNS recurrences – which continue to account for a large proportion of first-time recurrences [4]. Impressively, he said, the risk of brain metastasis increased steadily with the duration of the disease, apparently without reaching a plateau. This fact underlines the importance of developing therapeutic options and preventive measures.

Currently, the role of HER2-targeted tyrosine kinase inhibitors such as lapatinib and neratinib in the treatment of patients with CNS metastases is being investigated in particular. In combination with capecitabine, CNS response rates range from 18 to 66% with prolongation of progression-free survival (PFS) by approximately two months, depending on pretreatment [5]. Tucatinib appears to confer greater benefits in terms of overall survival and CNS recurrence compared with lapatinib and neratinib.

For example, CNS PFS of patients with active brain metastases in the randomized-controlled HER2CLIMB trial was 9.5 months with treatment with tucatinib compared with 4.1 months in the control arm [6]. Antibody-drug conjugates in the right combination may also have a future role in the treatment of HER2-positive breast cancer with CNS metastases, despite their size, according to Nancy Lin. For example, in 2020, corresponding results on the use of ADC T-DM1 were published [7]. Trastuzumab-deruxtecan could also come into play here – an approach that is currently being investigated.

Potentially promising is the combination of antibody-drug conjugates with HER2-targeted tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Previously dreams of the future, two studies are now underway to test precisely this basic idea. While the HER2CLIMB trial is looking at the combination of T-DM1 with tucatinib, the TBCRC 022 trial is looking at the combination of T-DM1 and neratinib.

Double HER2 blockade?

In addition to CNS metastasis, the choice of the optimal therapeutic sequence is also a major challenge – especially with the ongoing development of new agents and thus greater choice of compounds. At the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium , Nancy Lin focused on the usefulness of dual HER2 blockade after disease progression. She emphasized that the combination of trastuzumab and the TKI lapatinib, for example, could provide clinical benefits. Continuation of trastuzumab/pertuzumab treatment in parallel with TKI therapy was superior to TKI treatment alone, he said.

Even though there is increasing clarity on this point, many other questions remain unanswered. Thus, there is a lack of clear data on the sequential use of different tyrosine kinase inhibitors, including potential cross-resistance.

Futures: therapy stop and curative approaches

With the increasing number of long-term survivors, the question of whether and when to stop oncologic treatment during progression becomes pressing. Or to put it more provocatively: Are some of the patients cured? In the long-term analysis of the CLEOPATRA trial, as many as a quarter of participants were still relapse-free after eight years of first-line treatment [1]. In HER2+ breast cancer, there is still a lack of suitable markers for the recurrence of disease activity – comparable to minimal residual disease in leukemia – to ensure that therapy is stopped with as little risk as possible. Such a parameter is currently being sought and, according to Lin, could pave the way to a therapy-free life for affected individuals in the near future [8].

A primary curative approach is also possible based on current advances, the expert said. Especially in untreated metastatic HER2-positive breast carcinomas, so-called de novo cases, a cure is realistic, he said. This would thus be considered for 40% of patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer. For example, sequence therapy with THP (docetaxel, trastuzumab, and pertuzumab) followed by TDM-1/tucatinib, trastuzumab-deruxtecan, local methods, and maintenance therapy with HP (trastuzumab and pertuzumab) and tucatinib for one year is a possibility, he said.

Even if there is still a long way to go before curation and therapy stop, these are within reach thanks to the rapid developments of recent years. Lin even predicted fundamental changes in the treatment of metastatic HER2-positive breast cancer in the next decade, and concluded her talk by describing current research as leading the way. We stay tuned.

Source: San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium Dec. 8-11, 2020, ES7 Educational Session “Treatment of HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer – advances and challenges,” Nancy Lin (Dana-Faber Cancer Institute Harvard Medical School).

Literature:

- Swain SM, et al: Pertuzumab, trastuzumab, and docetaxel for HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer (CLEOPATRA): end-of-study results from a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2020; 21(4): 519-530.

- Modi S, et al: Trastuzumab Deruxtecan in Previously Treated HER2-Positive Breast Cancer. N Engl J Med 2020; 382(7): 610-621.

- Murthy RK, et al: Tucatinib, trastuzumab, and capecitabine for HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2020; 382(7): 597-609.

- Von Minckwitz G, et al: Trastuzumab emtansine for residually invasive HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med 2019; 380(7): 617-628.

- Freedman RA, et al: TBCRC 022: A Phase II Trial of Neratinib and Capecitabine for Patients With Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2-Positive Breast Cancer and Brain Metastases. J Clin Oncol 2019; 37(13): 1081-1089.

- Lin NU, et al: Intracranial Efficacy and Survival With Tucatinib Plus Trastuzumab and Capecitabine for Previously Treated HER2-Positive Breast Cancer With Brain Metastases in the HER2CLIMB Trial. J Clin Oncol 2020; 38(23): 2610-2619.

- Montemurro F, et al: Trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1) in patients with HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer and brain metastases: exploratory final analysis of cohort 1 from KAMILLA, a single-arm phase IIIb clinical trial. Ann Oncol 2020; 31(10): 1350-1358.

- Parsons HA, et al: Sensitive Detection of Minimal Residual Disease in Patients Treated for Early-Stage Breast Cancer. Clin Cancer Res 2020; 26(11): 2556-2564.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2021; 9(1): 26-27 (published 2/21, ahead of print).