The quality of life of patients with a leg ulcer is significantly reduced. In addition, this disease generates high costs due to loss of working days, high material costs, nursing support as well as long hospitalization times. Therefore, targeted diagnostics should be performed at the beginning and not just an expensive wound dressing applied.

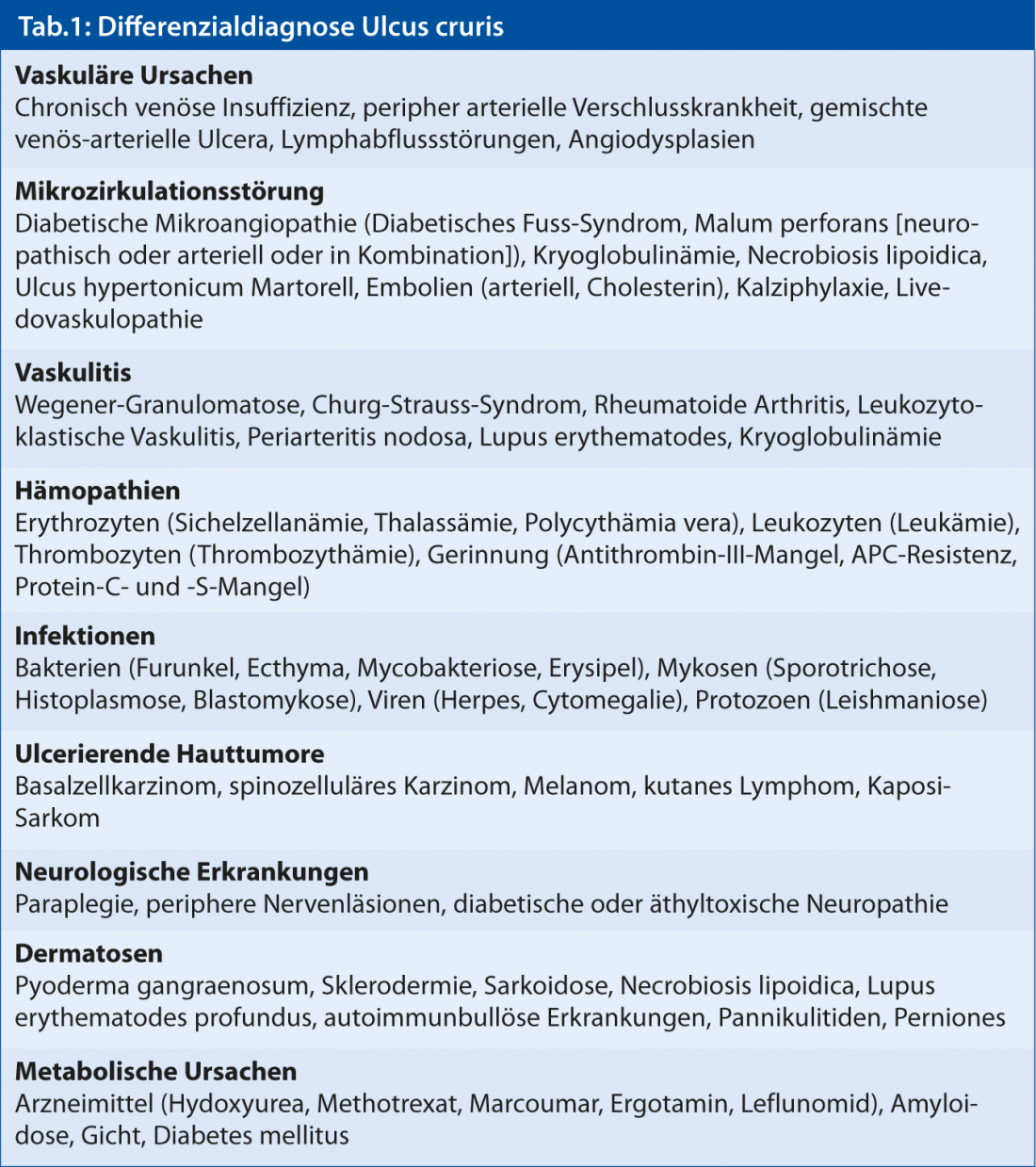

Although chronic venous insufficiency underlies 50-70% of all leg ulcers, arterial genesis in 5%, and mixed arterial-venous genesis in 10%, rarer causes with a wide spectrum of underlying diseases are responsible for symptoms in 10-20%. Up to 70 entities are described(Table 1). Therefore, a targeted diagnosis is indispensable for the success of the therapy.

The exact anamnesis is important

A detailed anamnesis about the duration, the course as well as possible triggering traumas should be performed at the beginning. Accompanying symptoms such as pain, limitation of walking ability, and joint discomfort can provide important clues. It is essential to record previous diseases (thromboses, vascular diseases, hematologic diseases), risk factors (arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, cigarette smoking, family history), and medication history.

Venous or arterial?

Since the most common etiologies each have a specific pattern, the clinical picture is of great importance.

The purely venous ulcers are usually located on the distal medial lower leg in the presence of saphenous vein insufficiency or on the dorsal dorsum of the foot in the presence of saphenous vein insufficiency (often in the setting of postthrombotic syndrome) within a skin zone with varicose veins, edema, eczema, hyperpigmentation, atrophie blanche, or sclerosis.

It should be noted that a history of varicosis or chronic venous insufficiency does not necessarily have to be the cause of the ulcer: 25% of the population is affected, and especially without the classic localization may be a coincidence.

Arterial ulcers of the lower leg are usually located over the lateral malleolus or pretibially. The ulcer appears punched out, has blackish necrotic portions (Fig. 1), and is often painful. The surrounding skin is often pale, atrophic shiny and without hair.

Fig. 1: Arterial ulceration

Mixed veno-arterial ulcers are often bimalleolar in location. These are venous ulcers with concomitant peripheral arterial disease. It is important to distinguish this entity because primarily peripheral arterial occlusive disease must be treated before the venous component can be addressed.

Hypertonic ulcer Martorell or pyoderma gangraenosum?

Highly characteristic is the laterodorsal localization for the ulcus hypertonicum Martorell. This is a stenosing arteriolosclerosis in the subcutis leading to a circumscribed painful skin infarction. Patients have been suffering from arterial hypertension for years. 60% also have diabetes mellitus. The diagnosis is confirmed with a deep biopsy. Often, after necrosectomy, split skin coverage is necessary.

This disease can easily be confused with pyoderma gangraenosum. In this case, the ulceration is triggered by a neutrophil-rich sterile skin inflammation, often after trauma, and is rapidly progressive. Approximately 50% of patients suffer from a systemic disease as underlying disease (ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, rheumatoid arthritis or myeloproliferative disorders). Clinically, pyoderma gangraenosum initially presents as erythematous nodules that exude and are surrounded by sterile pustules. The ulcerations are painful, polycyclic limited and have a livid, partly undermined rim. The diagnosis is made clinically; there are no specific laboratory tests or histologic diagnostic criteria. Therapeutically, high-dose immunosuppression is necessary.

More shapes

Vasculitic ulcerations (Fig. 2) are symmetrically distributed over the lower legs and, less frequently, in other locations and are usually accompanied by purpura.

Fig. 2: Vasculitic ulceration

Leukocytoclastic vasculitis is the most common form, but an ANCA-associated cause should still be sought serologically. Diagnosis of vasculitis requires biopsy for histology and direct immunofluorescence (material native or in Michel’s solution). In addition, organ involvement, especially glomerulonephritis, and infection (group A beta-hemolytic streptococci and viral hepatitis) should be excluded as triggers.

Infectious ulcers such as ecthyma (beta-hemolytic Strep A, less commonly Pseudomonas) may also present with a typical clinic. Without orientation to the anatomical structures are exogenously induced ulcerations. These are caused, for example, by trauma, such as the “stepping-stone ulcer,” a blunt contusion trauma, whereby a hematoma forms under atrophic senile skin. It is not uncommon to observe ulcerations on the lower legs after radio- and cryotherapy.

Malignancies also occur without specific localization. The primary malignancies are almost half basal cell and half spinocellular carcinoma, with other histiogenesis occurring in approximately 1-3% of cases (Kaposi’s sarcoma [Fig. 3], melanoma, cutaneous lymphoma, etc.). Secondary malignancies in chronic ulcers are often aggressive, moderately or poorly differentiated spinocellular carcinomas.

Fig. 3: Kaposi’s sarcoma

Therefore, a biopsy is recommended for all ulcerations that, despite adequate therapy, become larger or deeper after three months, form a tissue plus (“new” hypertrophic progressive margins), or are atypically localized.

Conclusion

Ultimately, a leg ulcer is a symptom of a wide variety of diseases. In addition to history and clinical status (including palpation with venous and pulse status), vascular diagnostics using duplex ultrasound may be necessary. In 10-20% of cases, further examinations (skin biopsy, etc.) are also necessary. Only with a clear diagnosis can a goal-oriented therapy be initiated.

Literature list at the publisher