Despite advances in combined radiochemotherapies, total laryngectomy still plays an important role in advanced laryngeal and hypopharyngeal carcinoma. Measures of oncological rehabilitation also include psychosocial aspects.

Despite advances in treatment protocols of combined radiochemotherapies, total laryngectomy still plays an important role in the treatment of advanced laryngeal and hypopharyngeal carcinoma. This surgery significantly changes a patient’s life and has drastic psychosocial consequences. In the following, individual aspects of this treatment will be discussed in more detail.

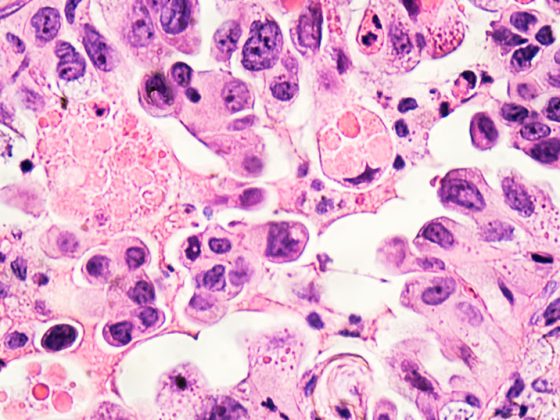

Laryngectomy is indicated for advanced laryngeal carcinoma with infiltration of the thyroid and or cricoid cartilage (Fig. 1). The primary tumor may also originate from the hypopharynx and infiltrate the larynx. If there is no cartilage infiltration, combined radiochemotherapy may be used as an alternative. In addition to this classic indication for laryngectomy for malignancy, the indication may rarely be for functional impairment or loss of function of the larynx. Thus, neurologic disease or postradiogenic sclerosis can lead to severe dysphagia with recurrent aspiration pneumonia. In the first step, patients receive a gastrostomy and are prohibited from peroral food and fluid intake. If repeated severe aspiration pneumonia occurs during the course, laryngectomy should be addressed.

Technique, reconstruction, adjuvant therapy

Classic laryngectomy usually involves removal of the thyroid, cricoid, and hyoid. The tracheal stump is sutured to the skin cranially and a tracheostoma is formed. The pharyngeal tube is closed primarily. This removes the tumor and separates the air and food passages. From then on, the patient breathes through the tracheostoma.

After tumor removal, it must be checked whether there is sufficient pharyngeal mucosa for primary closure. If this is not the case, reconstruction is necessary for sufficient swallowing function, which increases the morbidity of the procedure and thus the likelihood of later limitations. Here, pedicled local flapplasties such as the pectoralis major flap are available, or free flapplasties in which a microanastomosis is performed.

The extent of surgery and possible sequelae are defined by the tumor extent and the extent of cervical lymph node metastasis. Therefore, the functional outcome cannot always be compared in terms of swallowing and voice function. The greater the T and N stage, the greater the posttherapeutic limitations. Ideally, laryngectomy with primary closure of the pharynx is sufficient and does not require adjuvant therapy. Here, swallowing function and voice quality are often very good.

If cervical lymph node metastases are detected or if it is a primary hypopharyngeal carcinoma, adjuvant radiotherapy is necessary for locoregional control. If cervical lymph node metastases show extracapsular growth or if incomplete resection has occurred, chemotherapy should be given in addition to adjuvant radiotherapy. This, in turn, has a variety of side effects and can thus prolong the entire rehabilitation process.

Voice Rehabilitation

The first total laryngectomy was performed by Theodor Billroth in 1873. Even then, a first speaking valve cannula was described for voice rehabilitation by Carl Gussenbauer in 1874. Today, 3 main variants are available for voice rehabilitation.

The most common variant is the tracheoesophageal voice using a speaking valve. This is a semi-permanent implant that must be changed regularly, usually in the examination chair. This valve is inserted through the tracheostoma between the posterior tracheal wall and the esophagus. The main prostheses used in the region are Provox® and Blom-Singer® prostheses in various sizes and designs. The handling of the valve can usually be easily learned, but a regular change is necessary. On average, a change takes place every three months. Valves with a Teflon coating have a longer functional life. However, these are many times more expensive and a cost approval must be obtained from the health insurer before inserting this valve.

Another option for voice rehabilitation is esophageal voice, also called ructus replacement voice. Here, patients learn to generate mucosal vibrations in the pharyngoesophageal segment after swallowing air, which allows them to speak finger-free. However, this type of voice rehabilitation is difficult to learn and has taken a bit of a back seat with today’s options for using a speech valve.

An even rarer variant of voice rehabilitation is the so-called electrolarynx with the help of a Servox device. This device, which generates mechanical vibrations, must be pressed against the floor of the mouth for vibration transmission to the pharynx and oral cavity. The tongue and lips are then used for articulation. The generated voice sounds monotonous and mechanical.

Consequences and restrictions

As mentioned above, the extent of limitations is strongly dependent on the extent of surgery and any adjuvant therapy. A primary goal is to restore swallowing function with peroral feeding and voice rehabilitation.

The voice valve is usually inserted just before closure of the pharyngeal mucosa and can be used after a few days. There is an increased risk of pharyngocutaneous salivary fistula during procedures involving complex reconstructions or laryngectomies after radiotherapy. In these cases, the voice valve insertion is delayed after a few weeks and requires renewed general anesthesia. With a functioning speaking valve, patients can communicate normally and also make phone calls, but must use one hand to close the tracheostoma. For some time now, a so-called Provox® FreeHands FlexiVoice™ system has been available, which enables speech either finger-free or with manual closure of the stoma.

If the pharyngeal mucosa can be spared to the maximum extent during surgery, postoperative food intake is not restricted. If part of the mucosa must be removed or if scarring and loss of elasticity of the pharyngeal tube occur after radiotherapy, dysphagia may occur to varying degrees. Depending on the degree, meat and bread, for example, can be swallowed more poorly. If xerostomia is severe after radiotherapy, this additionally leads to a restriction of food intake. The food must be sufficiently moistened in each case.

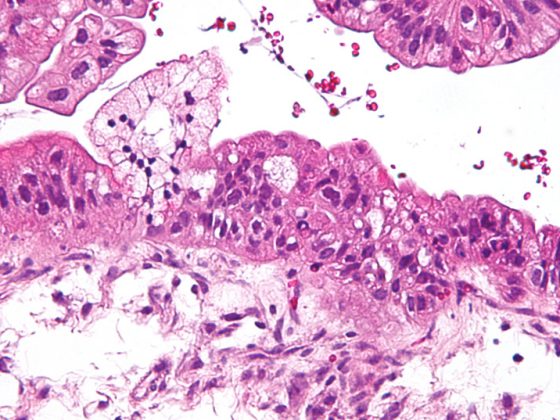

Patients after laryngectomy breathe through the created tracheostoma. This means that there is no nasal ventilation, which is why the sense of smell is reduced. Only very strong odors can be perceived. Voice and olfactory limitations are the most common problems reported by laryngectomized patients postoperatively. This is associated with difficulty eating in public and with friends, which is why there is a tendency to withdraw and reduce social contacts. Because of the tracheostoma, laryngectomized patients cannot swim and must be careful not to get water into the trachea when showering (Fig. 2).

Care tracheostoma

Because the airway is separated from the foodway, coughed-up secretions cannot be swallowed and must be removed from the tracheostoma. Secretion production is often high postoperatively, which is why a suction device is used initially. This device can be purchased or rented. Secretion production by the lungs is very individual and can significantly limit a normal daily routine. Regular suctioning is necessary, especially in the first months after surgery. In the long term, suctioning or inhalation is often no longer indicated.

If a speaking valve is used, it is necessary to clean the valve several times a day. For this purpose, the majority use a small brush (Fig. 3). A small balloon can also be used, which cleans the valve by means of air flow. (Fig. 4). The aim of valve care is to maintain the function of the valve in order to be able to speak at all, to avoid a valve defect caused by food debris and to reduce the biofilm of skin and pharyngeal flora with Candida, which destroys the silicone valve in the long term. The functional life of the valves varies, usually it is a few months.

During the second week after laryngectomy, patients usually begin to engage in tracheostoma care. This is done with a mirror and light. Learning how to use the device requires time and intensive nursing guidance. Often, there is an emotional hurdle to overcome in order to come to terms with the changed anatomy and new life circumstance.

For some years now, skin-friendly stoma patches have been used, which have to be changed regularly and allow the use of a filter with heat and moisture exchange of the respiratory air (Fig. 5) . Since then, the incidence of acute tracheitis has decreased significantly, especially in the winter months. Depending on the country and the extent of medical care, neck scarves are still used exclusively to protect the tracheostoma.

At the same time as learning to care for the tracheostoma, logopedic therapy begins to practice swallowing and speaking. The application of the speaking valve can take from a few days to several weeks of therapy. If radiotherapy takes place postoperatively, speech and also swallowing may be limited due to the side effects of the therapy. Radiation dermatitis temporarily makes it impossible to wear the stoma patch.

Ability to work and travel

Laryngectomized patients are usually able to travel and use airplanes, depending on their comorbidities. If you are using a speaking valve, we recommend that you carry a suitable plug for the valve (Fig. 6) . If a flap defect occurs in the speaking valve during the trip, this plug can be used to close the valve. This means that it is still possible to take in food and liquids, but speaking with the plug in place is no longer possible. After return, the speaking valve can then be changed. Depending on the destination and duration, patients also find out about a possible change of the speaking valve on site by a specialist. The use of the plug must also be learned. Each patient should be instructed in this regard. If a suction device is necessary, this should be certified by the attending physician so that it can be carried on the aircraft.

The ability to work must be assessed on an individual basis. In general, there is an inability to work if there are special hygienic requirements or a high level of dust and dirt in the workplace. A restriction is also given if the patient is particularly dependent on the sense of smell or voice when performing his or her work. If resumption of professional activity is sought, this should be done as expeditiously as possible at a low percentage to overcome the psychological hurdles and to increase the patient’s self-confidence. The Swiss Disability Insurance should also be involved as early as possible so that appropriate rehabilitation measures can be initiated. An important factor for the resumption of professional activity is the degree of professional qualification and the type of voice rehabilitation. Due to the circumstances of life, significantly more financial difficulties are to be expected post-therapeutically in younger patients who are pursuing a professional activity than in older patients who already receive a retirement pension and are thus financially secure.

Sexuality

Sexuality is rarely addressed as a rule. After a laryngectomy, there are no formal medical restrictions on being sexually active. Laryngectomized patients have to get used to the changed body perception. Time is needed for this. Of course, the side effects of the entire therapy must also be taken into account, especially any chemotherapy that has been administered and any side effects on the libido. A proportion of patients report limitations in sexual activity, but also a reduction in intimacy with their partner. Not infrequently, this topic is avoided in the relationship. It can therefore be helpful to include the topic in the psychological support of the patient and/or partner.

Psychosocial care

Preoperative education about the scope of the procedure and its consequences plays a critical role in patient satisfaction with care and involvement in decision making. It reduces affective stress, improves communication with family members, and impacts quality of life data postoperatively. Patients with advanced tumor extension often require more information preoperatively to assess the consequences of therapy. It is recommended that all patients have contact with affected other patients prior to laryngectomy. Here, regular exchange and contact with self-help organizations is important. This opportunity can also facilitate social re-integration later on.

Psychological support for patients and also their relatives is recommended. In addition to support regarding perceived helplessness and fears of recurrence, perioperative support is also useful with regard to leaving the voice as part of oneself. With appropriate psycho-oncological care, it may be possible to better process feelings of shame and reduce avoidance behaviors with social withdrawal. In this context, the role of the family doctor as a confidant, who can advise, support and motivate the patient, also plays an important role.

Take-Home Messages

- The extent of limitations in voice and swallowing function after laryngectomy and adjuvant therapy, if any, depends on the extent of the tumor disease.

- The most common and successful voice rehabilitation after laryngectomy is with a voice prosthesis, which must be changed regularly.

- Laryngectomized patients are usually able to travel and, depending on their occupation and skill level, may be able to return to work.

- The sense of smell is still present, but olfactory function is severely limited due to separation of the air and food pathways.

- Accompanying psychosocial care supports the processing of the disease, reduces fears and counteracts social withdrawal.

Further reading:

- Babin E, et al: Psychosocial quality of life in patients after total laryngectomy. Rev Laryngol Otol Rhinol (Bord) 2009; 130: 29-34.

- Bozec A, et al: Evaluation of the information given to patients undergoing total pharyngolaryngectomy and quality of life: a prospective multicentric study. Eur Arch of Oto-Rhino-Laryngol 2019; 276: 2531-2539.

- Costa JM, et al: Impact of total laryngectomy on return to work. Acta Otorrinolaringol Esp 2017; 69: 74-79.

- Eadie TL, et al: Coping and quality of life after total laryngectomy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2012; 146: 959-965.

- Low C, et al: Issues of intimacy and sexual dysfunction following major head and neck cancer treatment. Oral Oncol 2009; 45: 898-903.

- Moreno KF, et al: Sexuality after treatment of head and neck cancer: findings based on modification of sexual adjustment questionnaire. Laryngoscope 2012; 122: 1526-1531.

- Pereira da Silva A, et al: Quality of life in patients submitted to total laryngectomy. J Voice 2015; 29: 382-388.

- Perry A, et al: Quality of life after total laryngectomy: functioning, psychological well-being and self-efficacy. Int J Lang Commun Disord 2015; 50: 467-475.

- Roick J, et al: Social integration and its relevance for quality of life after laryngectomy. Laryngorhinootology 2014; 93: 321-326.

- Singer S, et al: Sexual problems after total or partial laryngectomy. Laryngoscope 2008; 118: 2218-2224.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2019; 14(12): 8-11