The benefits of statin therapy in secondary prevention should not be denied in principle to older patients at risk. Currently, statins have no value in primary prophylaxis in old age. The indication for lipid lowering in old age should be carefully considered, taking into account the patient’s individual situation and personal goals. Starting therapy with low doses and gradually adjusting the dose while monitoring potential side effects is recommended. Discontinuation of statin therapy should be evaluated regularly.

Life expectancy has increased significantly in recent decades, and the proportion of the population living to a ripe old age in particular is rising disproportionately. According to a trend scenario of the Swiss Federal Statistical Office, the number of people over 90 in Switzerland will more than double in 20 years. It is also assumed that of the children currently alive, one in two will reach the age of 100. will reach the age of 50.

Today, many diseases are treatable but not curable, so there are more and more chronically ill people. In the situation of very old age, polymorbidity and polypharmacy, one must rightly ask what should be treated and to what extent. We usually consult evidence-based guidelines here. Unfortunately, however, the evidence is extremely thin, especially in the very old segment, as there are still too few studies for this population. The guidelines of the respective professional societies are usually based on studies that do not include polymorbid, geriatric patients. Clarifications and treatments are therefore usually very individual and adapted to the respective patient goals.

Age and lipid status

Cardiovascular disease increases with age and is the leading cause of death. Hypercholesterolemia is one of the classic cardiovascular risk factors, along with age, arterial hypertension, smoking, and diabetes. Lipid metabolism changes with age: from adolescence to 50 years of age, LDL cholesterol levels increase steadily, then reach a plateau phase, only to drop again somewhat in older age.

In aged individuals, LDL receptor activity is reduced, reverse cholesterol transport is impaired, and both LDL and HDL particle size and functionality are altered. In malnutrition, which is common in old age, the LDL level additionally decreases. Thus, in old age, small doses of statins are sufficient to produce an effect. Low HDL cholesterol is also associated with up to a twofold increase in cardiovascular mortality in patients >85 years. In older age, the extent and instability of atherosclerotic plaques increase, so that the plaque-stabilizing effect of statins could be particularly beneficial here.

Lipid-lowering measures

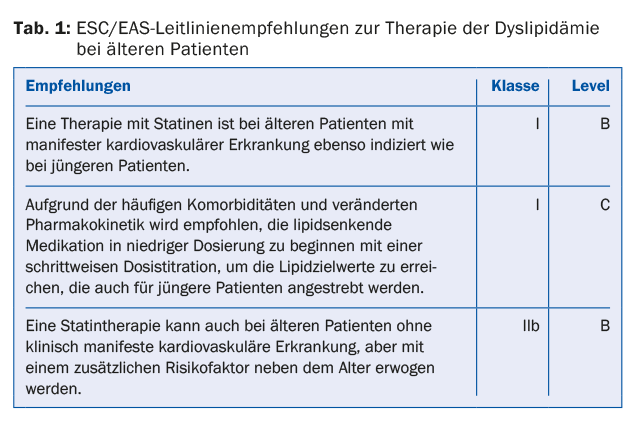

In November 2014, new guidelines on lipid therapy were published by the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology. In this, statins remain agents of first choice for cardiovascular risk reduction. However, the LDL target values aimed for so far are taking a back seat. The baseline risk is now relevant for the treatment decision. Since this risk profile was developed for the American population and the risk score has not yet been validated for Europe, the Swiss professional societies continue to adhere to the currently valid LDL target values of the ESC/EAS guidelines. There is no adjustment of values for age: in high-risk patients (known cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes), the LDL target value is <70 mg/dl, in high-risk patients (high-risk cardiovascular profile) <100 mg/dl, in moderately increased risk <115 mg/dl. Cardiovascular disease primarily includes coronary artery disease, condition after myocardial infarction, and condition after ischemic insult.

For the elderly, evidence on the effectiveness of lipid-lowering drug therapy is available mainly from statin studies. Fibrates should not be used in the elderly because no evidence of efficacy has yet been established for this age category.

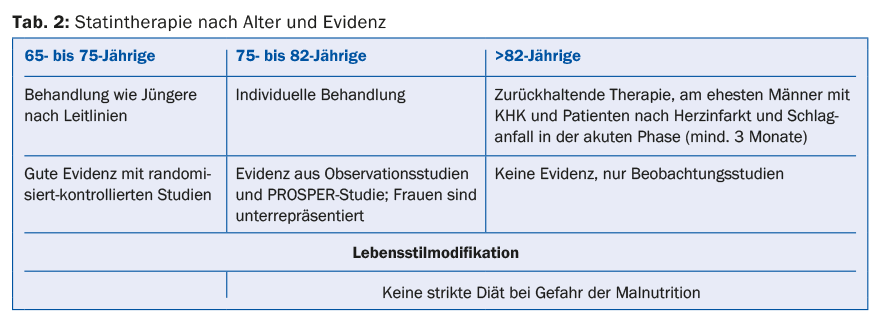

Even in old age, lifestyle interventions and dietary recommendations are considered important therapeutic pillars in the treatment of hyperlipidemia. The Mediterranean diet, in particular, has been well studied in this context, showing a reduction in cardiovascular events in patients aged 70 to 90 years. It should be noted, however, that strict dietary recommendations should be avoided in advanced age, as the risk of malnutrition is high.

Side effects and interactions

The side effects of statin therapy are often significant and can greatly reduce quality of life. These are primarily myopathies, bloating, triggering delirium, and a reduction in muscle strength with resulting falls. Muscular side effects are dose-dependent and manifest with muscle pain, an increase in creatine phosphokinase, and rarely rhabdomyolysis. Patients with hypothyroidism, renal insufficiency, or low body weight have an increased risk of myopathy. Liver failure is rarely observed, but discontinuation of the statin is recommended when transaminase levels increase threefold and other causes of transaminase elevation have been ruled out. There is also evidence that statin therapy slightly increases the risk of type 2 diabetes.

As a result of drug interaction, the plasma concentration of the statin may increase. This is the case, among others, with a combination of verapamil, diltiazem, and amiodarone with statins metabolized via the cytochrome P-450 mechanism (atorvastatin, simvastatin, lovastatin, fluvastatin). With the statins mentioned, a combination with grapefruit juice and St. John’s wort should also be avoided. Contraindicated when simvastatin is combined with macrolide antibiotics, ketoconazole, cyclosporine, gemfibrozil, and HIV protease inhibitors.

Evidence base

With regard to the reduction of cardiovascular events, study results on the effectiveness of statin therapy are also available for the elderly. The advantage in terms of cardiovascular risk reduction relates mainly to secondary prevention and here in particular to men, since except in the PROSPER trial women were significantly underrepresented. The prospective randomized-controlled PROSPER trial (“Pravastatin in elderly individuals at risk of vascular disease”) was the first to study pravastatin 40 mg daily vs. placebo in 5804 elderly patients (70-82 years). After a mean observation period of 3.2 years, the active treatment group was found to have a 34% reduction in LDL cholesterol, a 19% reduction in the rate of myocardial infarction and cardiovascular death, and a 24% reduction in cardiovascular mortality.

In a meta-analysis by Afilalo et al. a total of 19 569 patients aged 65-82 years were pooled from nine intervention studies. Here, statin therapy showed a reduction in all-cause mortality compared with placebo. 28 people need to be treated for five years to save a life. The study evidence also shows that with regard to secondary prevention of stroke, ischemic insults are prevented with statins, but hemorrhagic insults tend to occur more frequently. With regard to peripheral arterial disease, statin therapy shows an improvement in symptom-free walking distance and a reduction in postoperative mortality during peripheral vascular procedures.

The effect of statins on general health, cognitive function, and dependency on care in the elderly has also been studied. There are few studies on this and the results are contradictory. Current guidelines of international professional societies, such as those of the ESC/EAS, refer to the indication for statin therapy in the elderly (Table 1).

Practical procedure

65- to 82-year-olds can benefit from lipid lowering just as much as younger people. There are insufficient data for women, patients older than 82 years, and lipid lowering for primary prevention. Studies have shown the best effect in patients with coronary artery disease (especially men in this case) and in the secondary prevention of ischemic stroke. The use of statins after acute coronary syndrome is also useful, especially for a limited time after intervention. A possible decision guide by age and evidence is shown in Table 2.

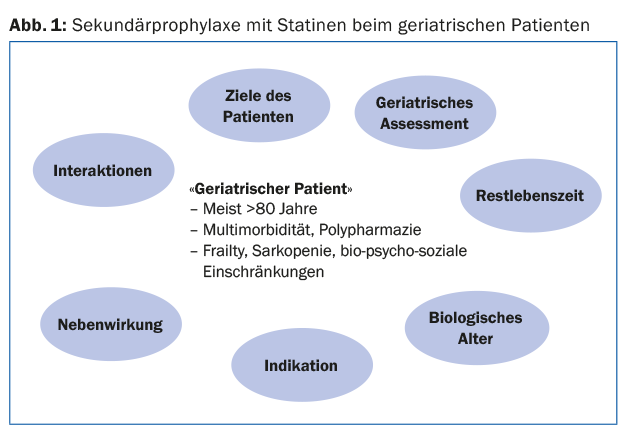

In general, in patients of advanced age and multimorbidity, polypharmacy and various bio-psycho-social limitations, it must always be decided on a case-by-case basis whether lipid-lowering therapy makes sense, is tolerated and whether the effect can be experienced at all. (Fig.1). A geriatric assessment can be helpful in making treatment decisions; it is also important to ask about the patient’s goals. When statin therapy is indicated in the elderly, low doses are sufficient to achieve lipid reduction.

When to stop statins?

Evaluation of statin therapy is certainly useful at nursing home entry if life expectancy is less than five years or if side effects occur. Likewise, lipid-lowering therapy should always be stopped if there is no indication, e.g., primary prophylaxis in >80-year-olds. Interruption of statin therapy in the acute phase of ischemic stroke is associated with an increased risk of death or neurologic disability within 90 days. Therefore, statin therapy should be continued continuously in the acute stage of stroke.

Further reading:

- Petersen LK, et al: Lipid-lowering treatment to the end? A review of observational studies and RCTs on cholesterol and mortality in 80+-year olds. Age and Ageing 2010; 39: 674-680.

- Lechleitner M: Lipid-lowering therapy in geriatric patients. Z Gerontol Geriat 2013; 46: 577-587.

- Hansbauer B: Statins in old age. Z Allg Med 2012; 88(9): 339-340.

- Miettinen TA, et al: Cholesterol-lowering therapy in women and elderly patients with myocardial infarction or angina pectoris: findings from the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S). Circulation 1997; 96: 4211-4218.

- MRC/BHF Heart Protection Study of cholesterol lowerin with simvaststin in 20536 high-risk individuals: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2002; 360: 7-22.

- Sheperd J, et al: Pravastatin in elderly individuals at risk of vascular disease (PROSPER): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2002; 360: 1623-1630.

- Afilalo J, et al: Statins for secondary prevention in elderly patients: a hierarchical Bayesian meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008; 51: 37-45.

- Perk J, et al: European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice (version 2012). Eur Heart J 2012; 33: 1635-1701.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2016; 11(3): 11-13