The knee joint has a complex structure and is one of the most mechanically stressed joints in humans. In addition to traumatic, inflammatory and degenerative joint damage, septic or aseptic osteonecrosis may also occur in the joint area. Bone necrosis due to infection is usually associated with osteomyelitis, and the cause of aseptic bone necrosis is often unclear.

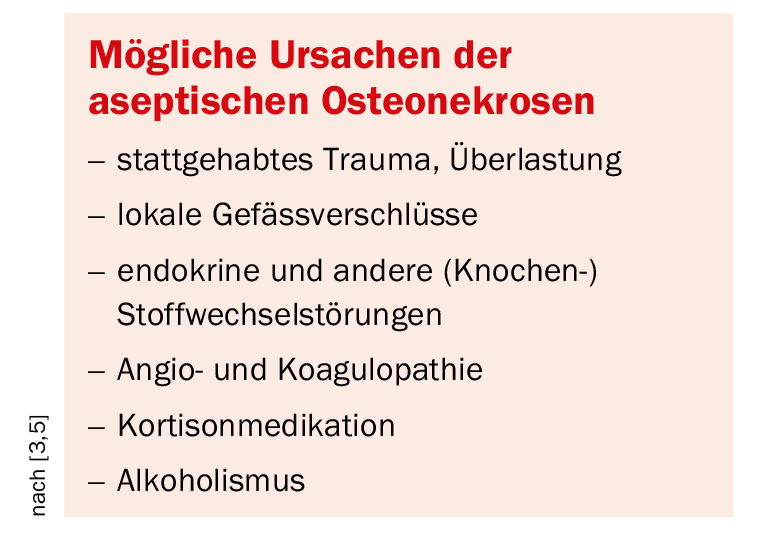

Possible causes of aseptic osteonecrosis are in the Box listed. They are more common on the lower extremities than on the upper and show typical localizations on the skeleton, often named after the first describer [6]. Secondary aseptic osteonecrosis is usually the result of ongoing drug therapy.

The normal tibial tuberosity undergoes different histological stages of development: cartilaginous apophyseal epiphysisal bony fusion with the tibia [8]. If recurrent microtrauma occurs during growth, the development of aseptic juvenile osteonecrosis may follow.

At the knee joint, osteonecrosis of the tibial apophysis, Osgood-Schlatter disease, is an important form of juvenile aseptic osteonecrosis. Children between 3 and 7 years of age are particularly affected, and another age peak exists in boys between 12 and 15 years of age. However, today there is also a clear progression of Osgood-Schlatter in girls at that age, triggered by increasing sports activities. Dysbalances of the thigh musculature, primarily shortening of the rectus femoris muscle, or paralysis of the quadriceps muscle and resulting changes in biomechanics play a role.

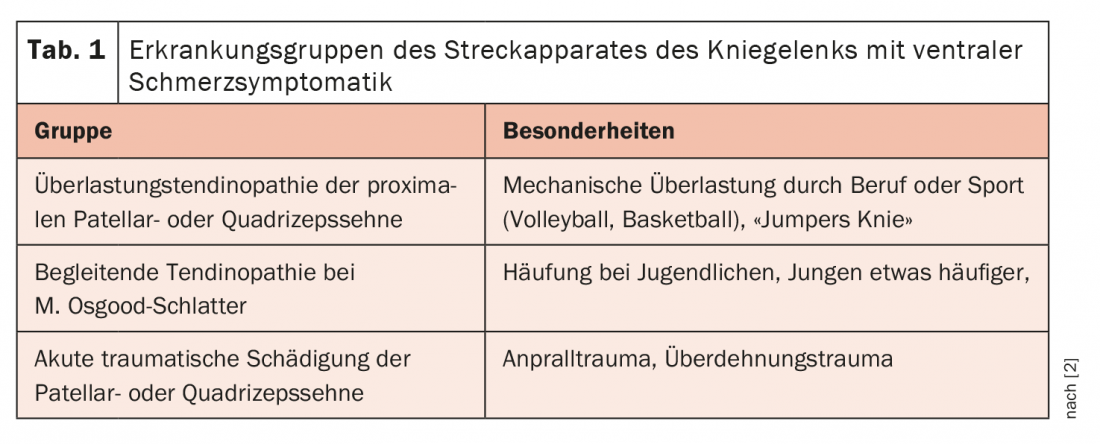

Infrapatellar pain during quadriceps tendon pull (knee flexion) or triggered by pressure (kneeling) is directional. Local swelling in the area of the tibial tuberosity is also often conspicuous. The knee joint itself is uninvolved in pretibial irritation. In terms of differential diagnosis, 3 groups of diseases can be differentiated in the region of the extensor apparatus of the knee joint (Table 1).

In about 90% of cases, conservative treatment measures can achieve a lasting improvement of the symptoms. Physical rest (possibly for months), elimination of quadriceps traction by bandaging, and application of heat are helpful, supplemented by appropriate drug therapy [7]. In the course, deformations of the tuberosity develop, fragmentations or cranially directed exostosis-like extensions are possible. The patellar tendon may be prone to early tendinosis or even recurrent inflammation. Correspondingly, deformities at the inferior patellar pole have also been described, Sinding-Larsen-Johansson disease [1].

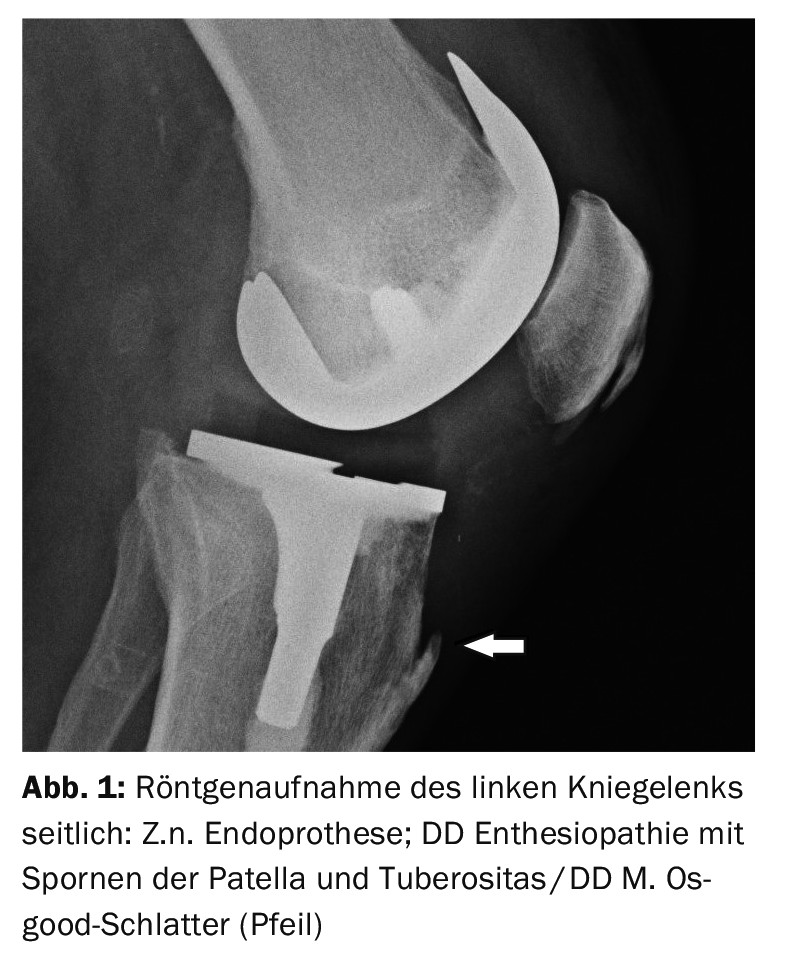

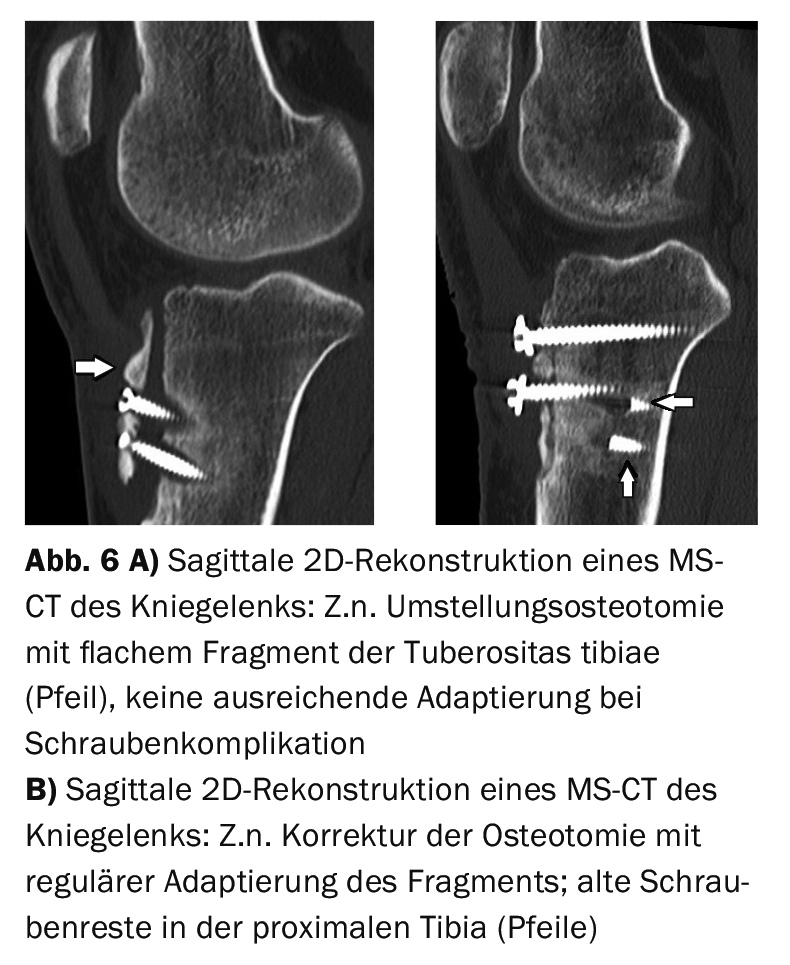

Radiographs in lateral projection can document the bony deformities of the tibial tuberosity very well, but do not tell us anything about the extent of local soft tissue inflammation or bony irritation. Computed tomographic studies, particularly sagittal 2D reconstruction of axial scans, demonstrate the bony changes of Osgood-Schlatter disease. However, soft tissue contrast is significantly reduced compared to MRI and thus local inflammation of the patellar tendon, bursitis, or Hoffitis may escape detection.

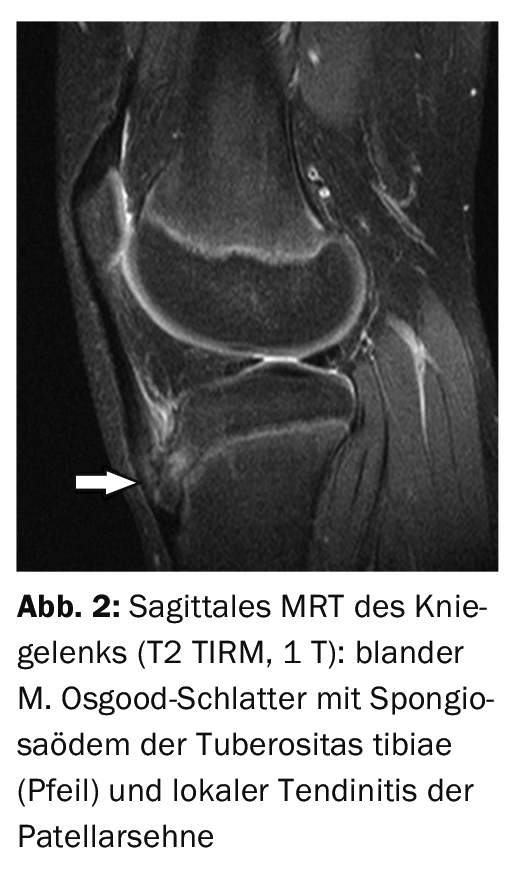

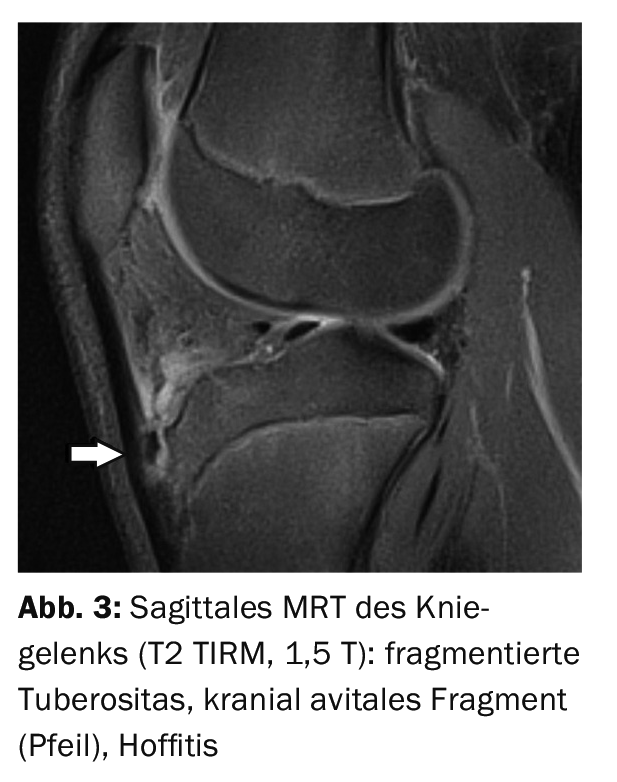

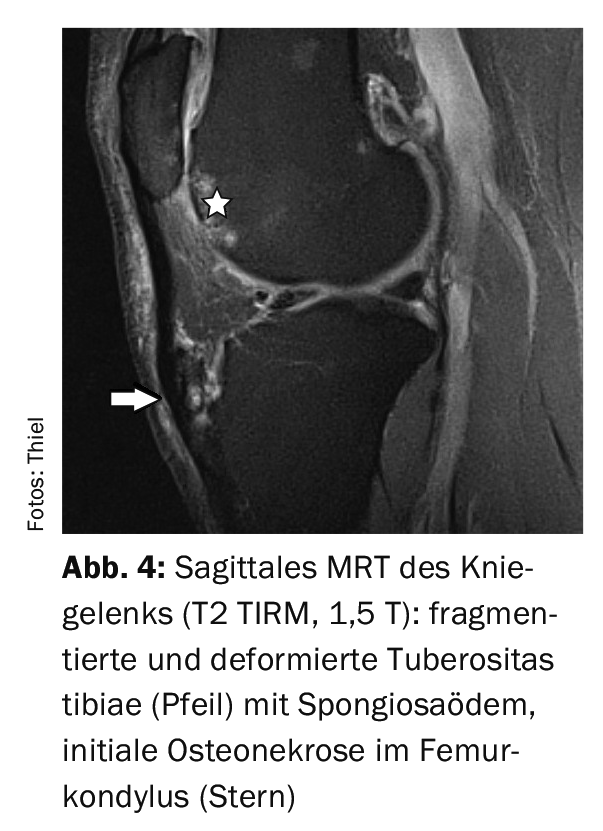

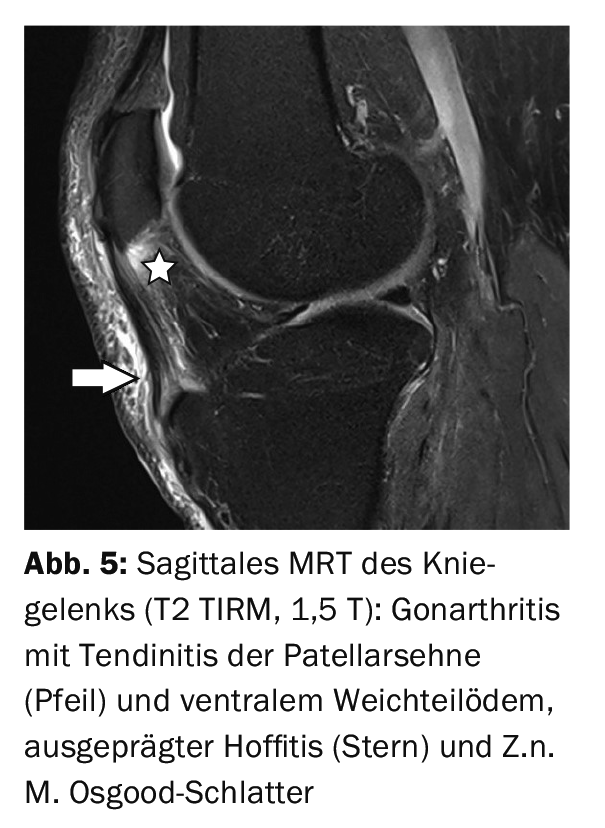

The purpose of MRI is to verify the full extent of the local inflammatory reaction: Soft tissue edema, tendinosis or tendinitis, bursitis, hoffitis, and also spongiosa edema of the tuberosity. Fat-suppressing sequences [6,8] are excellent for this purpose, and contrast medium support is not obligatory. The use of T1w or T2w sequences allows differentiation of concomitant chronic or acute alterations of the patellar tendon.

Case studies

All demonstrated case reports of Osgood-Schlatter disease were male patients, and the conversion osteomy with complication involved a female 18-year-old.

In case report 1, a lateral radiograph of the left knee joint (Fig. 1) for control after prosthesis implantation in a 79-year-old patient shows a bone spur at the attachment of the patellar tendon with palpable bony resistance, image morphologically not the typical situation of old Osgood-Schlatter disease. Case report 2 shows an initialOsgood-Schlatter‘s disease in a 13-year-old boy (Fig. 2) with spongiosa edema with preserved shape and contour, accompanied by perifocal soft tissue inflammation. Case example 3 demonstrates an avital fragment (Fig. 3) of the tuberosity in a 16-year-old adolescent already suffering from Osgood-Schlatter disease with local soft tissue inflammation.

Case report 4 shows the situation of an activated Osgood-Schlatter disease with spongiosa edema and fragmentation (Fig. 4) after impact trauma in a 53-year-old patient as well as significant soft tissue edema. Case study 5 offers a Z.n. M. Osgood-Schlatter with deformed tuberosity without inflammatory bone reaction rather incidentally in an arthritis of the knee joint with pronounced inflammatory soft tissue reaction (Fig. 5). At Case report 6 documents the course of patellar tendon conversion after patellar dislocation in femoropatellar dysplasia (Fig. 6A and 6B).

Again, there was significant infrapatellar discomfort, but this was based on a lack of bony consolidation of the tibial tuberosity at screw fracture. The bone fragment was not adequately adapted to the proximal tibia. Corrective surgery then brought fixation and a significant improvement in symptoms.

Take-Home Messages

- Osgood-Schlatter disease is one of the aseptic juvenile osteonecroses.

- Localized at the tibial tuberosity, it is the result of mechanical overload during bone growth.

- Male children and adolescents are primarily affected.

- The imaging technique used to detect Osgood-Schlatter disease and local inflammatory reactions is magnetic resonance imaging.

- The therapeutic approach is primarily conservative with consistent offloading and symptomatic drug therapy.

Literature:

- Achar S, Yamanaka J: Apophysitis and Osteochondrosis: Common Causes of Pain in Growing Bones. Am Fam Physician 2019 May 15; 99(10): 610-618.

- Breitenseher M: The MR trainer. Lower extremity. Georg Thieme Verlag Stuttgart, New York 2003; 176.

- www.leading-medicine-guide.de/erkrankungen.

- Ladenhauf HN, Seitlinger G, Green DW: Osgood-Schlatter disease: a 2020 update of a common knee condition in children. Curr Opin Pediatr 2020; 32(1): 107-112.

- Launay F: Sports-related overuse injuries in children. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2015; 101(1 Suppl): 139-147.

- Rehart S, Sell S (eds.): Orthopedic rheumatology. Georg Thieme Verlag Stuttgart, New York 2016; 56.

- Schrouff I, Magotteaux J, Gillet P: How I treat… Osgood-Schlatter disease. Rev Med Liege 2015; 70(4): 159-162.

- Stoller DW: Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Orthopaedics and Sports Medicine.3rd edition, Volume one – lower extremity. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Baltimore 2007; 630.

InFo PAIN & GERIATry 2021; 3(1): 30-31.