Infective endocarditis is an infection of the endocardium and particularly the valve leaflets with an annual incidence of 3-10/100,000 persons. With high mortality and morbidity, prevention strategies such as adherence to antibiotic prophylaxis (AP) in patients with pre-existing cardiac conditions are of the highest priority. Current guidelines limit AP to high-risk patients and procedures primarily in the oral/dental area.

Infective endocarditis (IE) is an infection of the endocardium and, in particular, the valve leaflets, with an annual incidence of 3-10 per 100,000 persons [1–3]. The main feature of IE is infected valvular vegetations, which can embolize in the body and form further septic foci of infection. The prognosis of the disease is poor with in-hospital mortality of 15-20% and one-year mortality of 30% [1,4]. Morbidity in survivors is high, with residual risk of recurrence, new infection, or progressive deterioration of valve function, which may be associated with heart failure and the need for further medical and surgical intervention [1,4]. Thus, despite improvements in medical and surgical therapies within the last 30 years, IE still remains one of the deadliest infectious diseases.

With persistent high mortality and morbidity, prevention strategies, such as adherence to antibiotic prophylaxis (AP) in patients with pre-existing cardiac conditions, are of the highest priority. AP guidelines on endocarditis were first established by the American Heart Association (AHA) in 1955, and the guidelines have changed significantly since their inception. Thus, many countries and professional societies have modified the guidelines and adapted them to your own needs. In addition, a simplification took place in 2008.

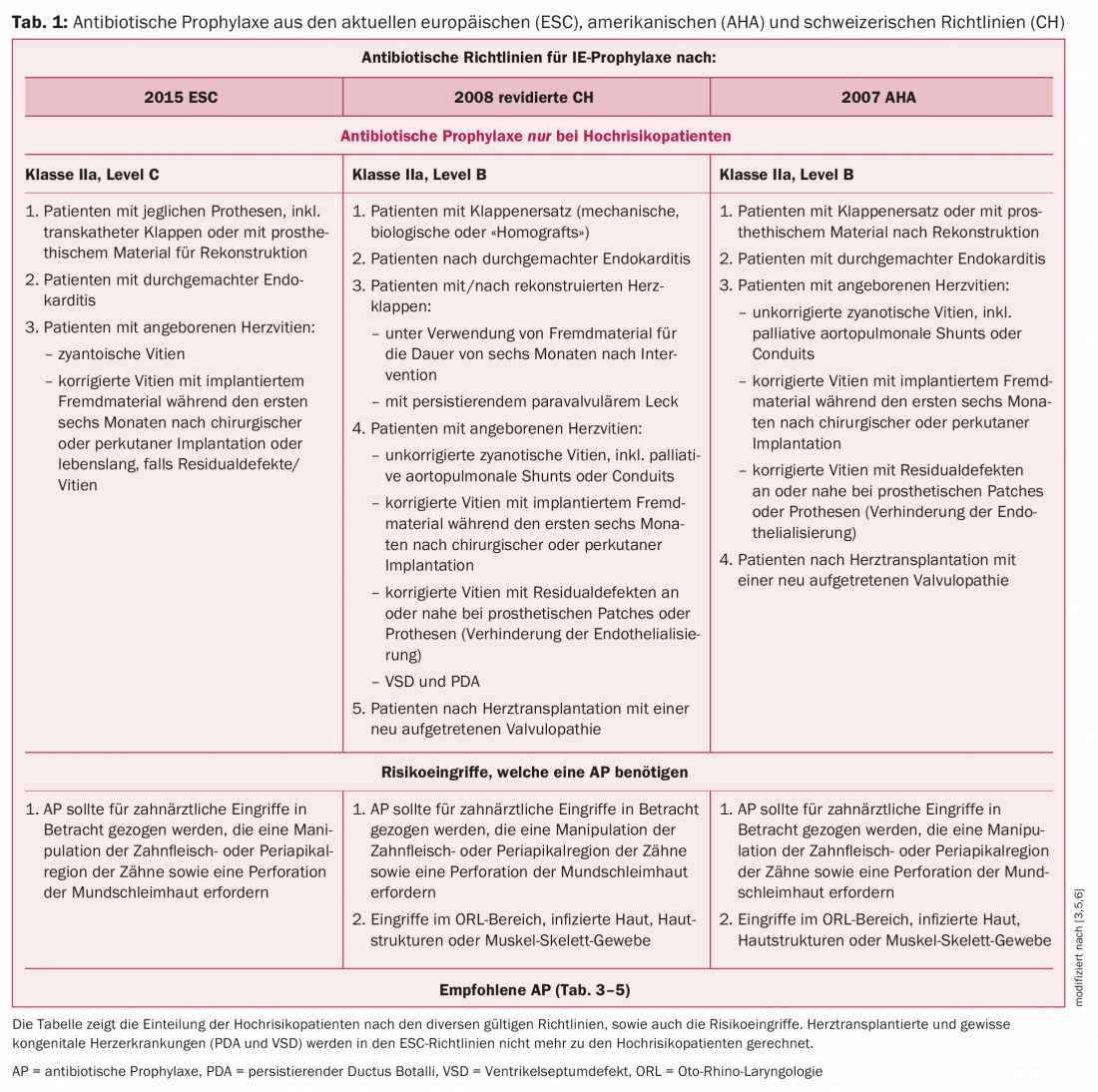

The need for antibiotic shielding has been limited to high-risk patients, with patients at intermediate IE risk no longer included in most current guidelines. These include bicuspid aortic valve, mitral valve prolapse, and ventricular septal defect (VSD) and persistent ductus botalli (PDA). Due to a lack of clinical data (especially the lack of a randomized controlled trial on the topic), AP to prevent IE remains a controversial topic. Currently, the following guidelines are valid for Switzerland: the AHA guidelines of 2007 [3], the AP guidelines revised in 2008 by Flückiger et al. [5] and the 2015 ESC guidelines [6]. Since 2008, the Swiss endocarditis prophylaxis guidelines [5] have not been revised. As there are certain divergences with the ESC Guidelines 2015 [6] on the topic, we would like to take this as an opportunity to discuss certain points and innovations.

Historical background: path to simplification and restriction

IE as a disease entity was first described in 1870 by Winge et al. described [8]. The hypothesis that bacteria can enter the circulation during an invasive dental procedure and thus cause IE was first proposed by Lewis and Grant in 1923, although it was not proven until 1935 by Okell and Elliott. Thus, these authors were able to deduce that 61% of patients have positive blood cultures for Streptococcus vir idans after tooth extraction, and Streptococcus viridans is known to be identified as the causative pathogen in 40-45% of IE cases. Knowing the antimicrobial activity of sulfonamides, it was first postulated in 1930 that AP could lead to a reduction in the incidence of IE. First Hirsch et al. showed a reduction in streptococcal bacteremia with penicillin in a randomized trial, paving the way for the first official AHA guidelines for endocarditis prophylaxis in 1955.

Swiss Endocarditis Prophylaxis Guidelines

After Moreillon published the first Swiss guidelines on the subject in 2000 [9], the guidelines were considerably simplified in 2008. This was based on the following considerations:

- Daily activities such as brushing or chewing are more likely to cause IE than dental surgery

- Even if an AP is 100 percent effective, AP can prevent only a small number of IEs

- High-risk patients are more likely to have a lethal course of IE than other patients

- Side effects of antibiotics and their cost must be considered.

The 2008 revised Swiss guidelines for endocarditis prophylaxis [5] are based on the 2007 AHA [3] and the 2007 German AP guidelines [10]. The use of antibiotic prophylaxis to prevent IE is generally considered justified because IE is rare but associated with high mortality and morbidity. In addition, brief drug prevention is preferable to prolonged therapy of infection, especially in patients with previous cardiac disease or previous IE episodes who are at risk of recurrence. In addition, bacteria of the oral flora, gastrointestinal and genitourinary tracts can promote IE. Ultimately, the efficacy of an AP to prevent IE could only be demonstrated in animal experiments, but an AP is almost certainly effective in humans.

Non-specific, general perioperative measures

It is important to adhere to general perioperative measures such as thorough dental, oral, and skin hygiene for all patients, especially for the high-risk group [6]. Good oral hygiene is much more important than an antibiotic at some point in life in all cases, as bacteremia occurs daily even when chewing and brushing teeth. Avoiding piercings and tattoos is also very important in this context. If wounds exist at the time of surgery, then they should be carefully disinfected. In addition, any infectious foci should be properly treated with antibiotics and any pathogens eradicated to reduce bacterial colonization. In high-risk patients, the indication for central venous catheters and invasive examinations should be reserved, and hospital hygiene measures should be urgently observed.

Indications for endocarditis prophylaxis

AP is recommended only in high-risk patients undergoing very defined procedures that are associated with an increased risk of bacteremia (Table 1) . Patients receiving perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis do not require endocarditis prophylaxis because the bacteria encountered during the intended surgery are already covered by the administration of the specifically chosen antibiotic.

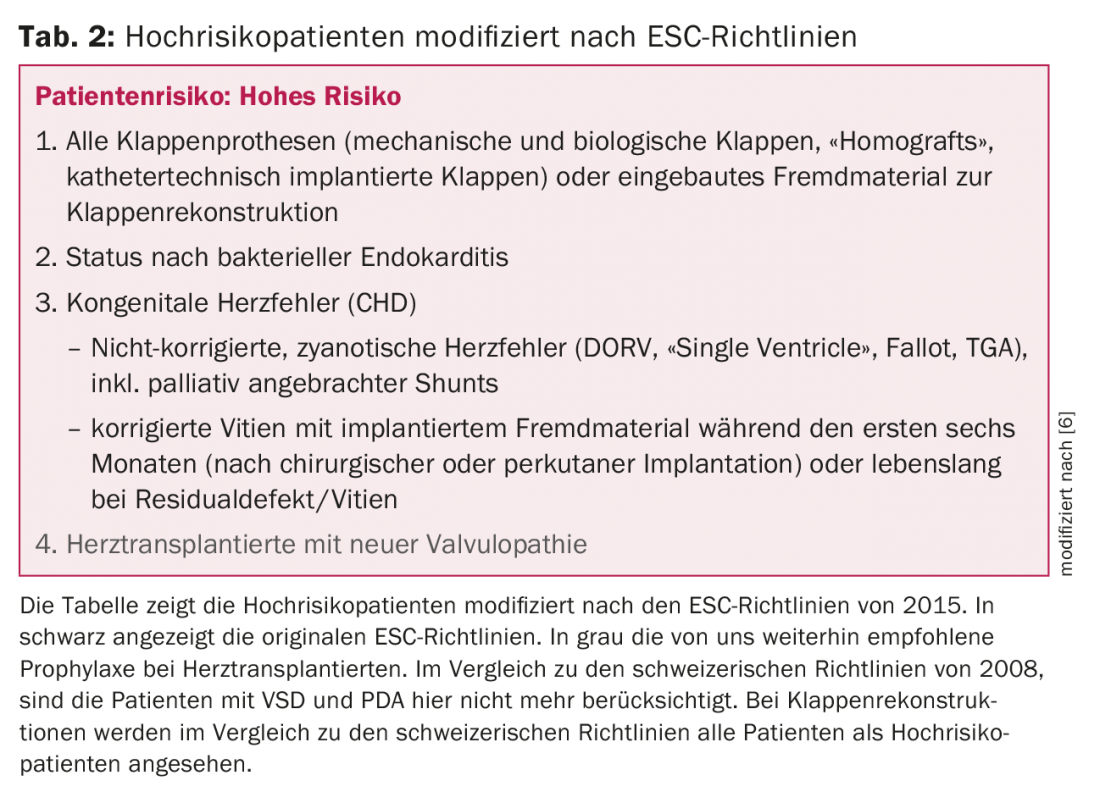

High-risk patients are defined differently depending on the guidelines. Roughly summarized, this group can be divided into patients with prosthetic material, patients with congenital heart disease or previous endocarditis. While the AHA and Swiss guidelines still included heart transplant patients among those at risk, the 2015 European guidelines no longer consider this group for endocarditis prophylaxis. This is a controversial topic and different views on the subject exist depending on the working group. Because of immunosuppression with poor outcome in IE as well as frequent valvulopathy (e.g., tricuspid regurgitation secondary to repeated cardiac biopsies), we continue to recommend AP before high-risk interventions, in contrast to the ESC guidelines. For details on the definition of high-risk patients, see Table 1 and Table 2.

Classification of AP according to interventions/interventions and organ systems.

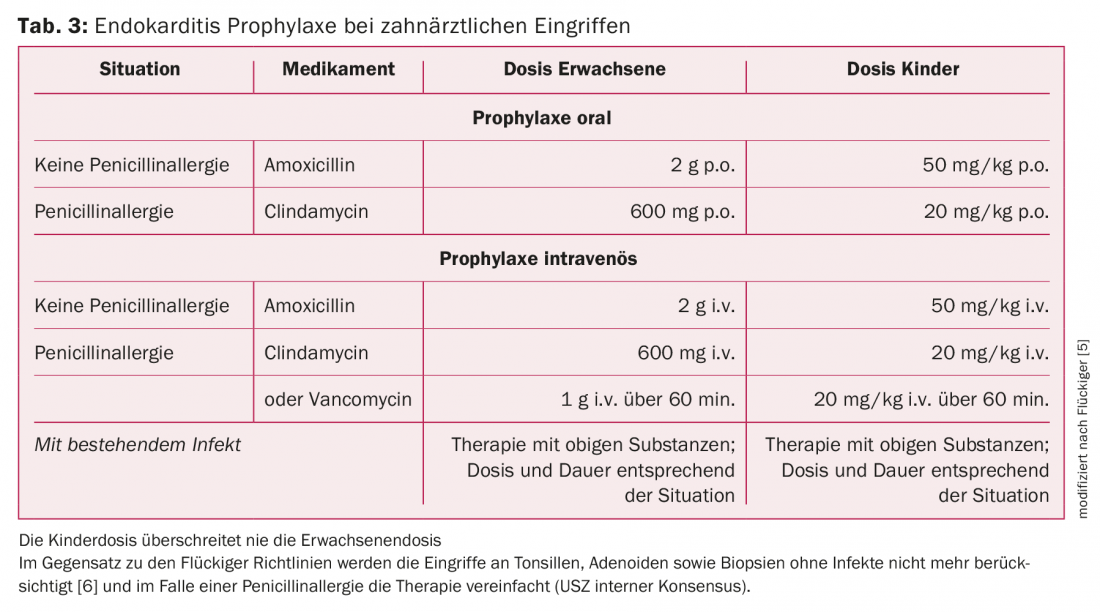

AP is defined as a single dose (peroral or parenteral) of an antibiotic administered 30-60 minutes before the intervention. The goal is to maximize the effectiveness of the antibiotic during the procedure. For small interventions, mostly dental procedures or skin procedures, peroral administration is favored; for larger interventions and/or anesthesia, parenteral administration is favored. AP as a single dose before intervention is limited to dental procedures to prevent the development of IE as a result of transient bacteremia. All other respiratory tract, skin, genitourinary tract, and gastrointestinal tract procedures without evidence of infection are no longer indications for AP [6]. An important exception is elective abdominal surgery, where a single parenteral dose is recommended (perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis). For preexisting infections, AP should be considered the first dose of a more prolonged and necessary antibiotic treatment. In this case, we recommend consulting an infectiologist in order to optimally adjust the antibiotic therapy. Dose recommendations for single AP prophylaxis assume normal renal and hepatic function. Dose adjustment is not usually necessary for single doses, but is of course required for longer-term therapies. AP guidelines for children are very similar to those for adults. The only difference here is the dosage of antibiotics.

Dental procedures

Teeth and/or jaws: The main prerequisite to reduce IE frequency is good oral hygiene, as everyday manipulations in the oral cavity, such as brushing teeth, can cause bacteremia. For patients at risk, a dental check-up twice a year is indicated. AP is indicated for dental manipulations that involve the gingiva or periapical region of the teeth or perforate the oral mucosa (extractions, surgical procedures, abscess treatments, periodontal therapy, biopsies). The most common pathogens in the oral cavity that can cause IE are the streptococci of the viridans group and, accordingly, penicillin or amoxicillin are the antibiotics of first choice. In the case of penicillin allergy, the Swiss guidelines for the choice of antibiotics distinguish between late-type reaction (cefuroxime) and immediate-type reaction (clindamycin). In the ESC guidelines, this is simplified and any penicillin allergy is simply treated with clindamycin. For details on the recommended AP, see table 3.

Non-dental procedures

Respiratory tract: In the 2008 Swiss guidelines, AP was generally considered indicated. Considering the ESC guidelines 2015, we consider AP for bronchoscopy, laryngoscopy or intubation no longer indicated. AP is also not indicated for tonsillectomy or adenotomy unless an infection is present. High-risk patients (Tab. 2) who receive an invasive procedure to treat an established infection (abscess drainage), however, should receive prophylaxis or therapy analogous to the procedure for dental interventions (Tab. 3).

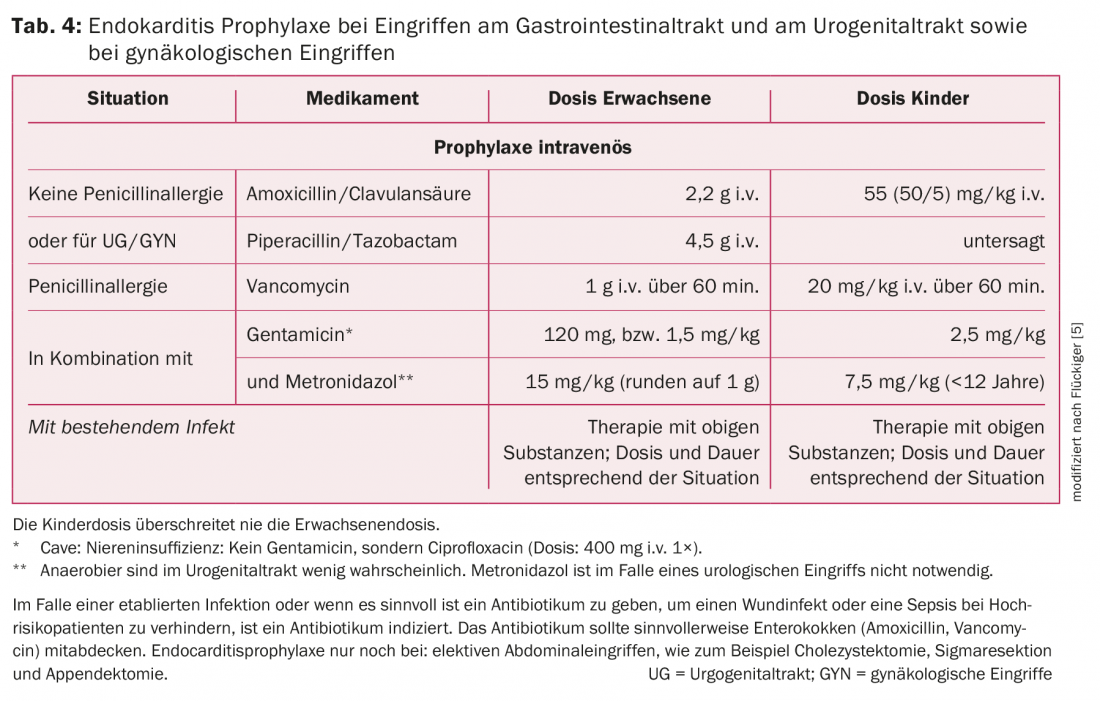

Gastrointestinal tract: Most gastrointestinal tract procedures, such as endoscopies (gastroscopy or colonoscopies with or without biopsy), do not require AP. In contrast, in the case of an established infection or when it is appropriate to give an antibiotic to prevent wound infection or sepsis in high-risk patients, an antibiotic is indicated. In addition, elective abdominal procedures (cholecystectomy, sigmoid resection, appendectomy) are an indication for AP. Here, parenteral AP is recommended 30 minutes before intervention. Therapy of choice is amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, as the aim here is to cover enterococci and anaerobes. In cases of penicillin allergy, vancomycin is indicated, although substances active against Gram-negative and anaerobic bacteria must be supplemented here.

In pre-existing infections, AP is the first dose of prolonged and necessary antibiotic therapy. Again, an antibiotic with activity against enterococci, gram-negative, and anaerobic bacteria is recommended For details on AP recommendations in the gastrointestinal tract, see Table 4.

Genitourinary tract: surgery or endoscopic procedures in the presence of sterile urine or absence of infection do not require AP. If an infection is present, an antibiotic with enterococcal activity must be chosen. Under certain circumstances, supplementation with a preparation against Gram-negative germs is advisable (Tab. 5).

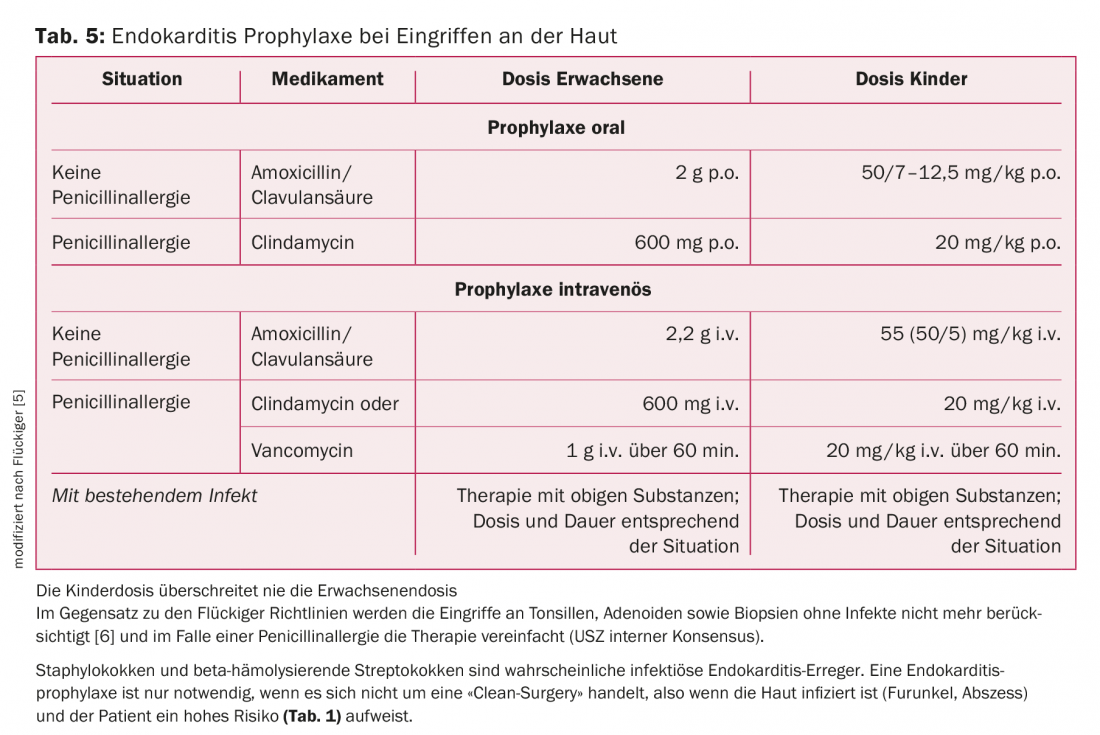

Skin: The most common pathogens in skin infections are staphylococci and streptococci. AP is only indicated if it is not a “clean-surgery”, i.e. if the skin is infected (boil, abscess) and the patient is at high risk (Tab. 2). Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid is the treatment of choice (Table 5).

Discussion

Infective endocarditis remains one of the deadliest infectious diseases and thus prevention is the best therapy for IE. For this reason, we generally recommend AP to avoid IE despite a lack of data and consensus. The issue remains highly contentious and there is divergence in treatment within the same working groups. We propose the last ESC guideline as the main reference for endocarditis prophylaxis. Removal of heart transplant patients from the high-risk group remains unclear to us. For these patients, we always recommend consultation with the attending cardiologist prior to high-risk surgery.

From our point of view, the AP of the Swiss guidelines for dental interventions can be simplified and adapted to the ESC guidelines. Adjustment according to allergy type seems rather cumbersome to us in everyday life. We have adjusted this accordingly in our internal guidelines. In the Swiss guidelines, AP without active infection is recommended only for dental and certain respiratory tract procedures. The ESC guidelines, on the other hand, only consider dental procedures as high-risk interventions. In any case, a rehabilitated own dentition seems to be one of the most important prophylactic measures.

More focused and prospective studies should ultimately clarify the long-standing issue and provide better data on the risk of adverse events of antibiotics in IE. The new AHA guidelines are planned for 2018 and, if necessary, these will give us insight into new aspects and topics for renewed discussion.

Take-Home Messages

- Because a striking association was noted between dental procedures, subsequent transient bacteremia, and infective endocarditis, guidelines for endocarditis prophylaxis were first established by the American Heart Association (AHA) in 1955.

- These guidelines have been revised and simplified several times since they were written and when data were insufficient.

- Current guidelines limit antibiotic prophylaxis (AP) to high-risk patients and procedures primarily in the oral/dental area.

- Unfortunately, there is no consensus on this – different guidelines define high-risk patients differently in each case. Following the recently published guidelines of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC), we recommend adherence to AP when manipulating the gingiva or periapical region of the teeth in this high-risk group.

Literature:

- Cahill TJ, Prendergast BD: Infective endocarditis. Lancet 2016; 387(10021): 882-893.

- Achermann Y, et al: Prosthetic valve endocarditis and bloodstream infection due to Mycobacterium chimaera. J Clin Microbiol 2013; 51(6): 1769-1773.

- Wilson W, et al: Prevention of infective endocarditis: guidelines from the American Heart Association: a guideline from the American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease Committee, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, and the Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group. Circulation 2007; 116(15): 1736-1754.

- Hoen B, Duval X: Infective endocarditis. N Engl J Med 2013; 369(8): 785.

- Fluckiger U, Troillet N: [New Swiss guidelines for the prevention of infective endocarditis]. Rev Med Suisse 2008; 4(174): 2134-2138.

- Habib G, et al: 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of infective endocarditis: The Task Force for the Management of Infective Endocarditis of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Endorsed by: European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS), the European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM). Eur Heart J 2015; 36(44): 3075-3128.

- Habib G, et al: Guidelines on the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of infective endocarditis (new version 2009): the Task Force on the Prevention, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Infective Endocarditis of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Endorsed by the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) and the International Society of Chemotherapy (ISC) for Infection and Cancer. Eur Heart J 2009; 30(19): 2369-2413.

- Contrepois A: Notes on the early history of infective endocarditis and the development of an experimental model. Clin Infect Dis 1995; 20(2): 461-466.

- Moreillon P: Endocarditis prophylaxis revisited: experimental evidence of efficacy and new Swiss recommendations. Swiss Working Group for Endocarditis Prophylaxis. Schweiz Med Wochenschr 2000; 130(27-28): 1013-1026.

- Naber CK, et al: New guidelines for infective endocarditis: a call for collaborative research. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2007; 29(6): 615-616.

CARDIOVASC 2017; 16(6): 3-8