Lung cancer is the most common fatal cancer worldwide, and its incidence is still increasing in modern times. Despite advances in diagnosis and treatment, the lethality of lung cancer leads both sexes compared with all other cancers. Basically, small cell lung carcinomas are distinguished from non-small cell lung carcinomas, which is of central importance for the therapy regime and prognosis. While small cell lung cancer is the domain of chemotherapy and radiotherapy, non-small cell lung cancer (“NSCLC”) is operated on in the localized stage and a cure can be achieved with this. In this review article, only the follow-up and prognosis of NSCLC operated on with curative intent is discussed.

Since lung cancers are often diagnosed at an advanced and often already metastasized stage, only about 25-30% of all “non-small cell lung cancer” (NSCLC) can be submitted to surgery [1]. The prerequisite for a surgical therapy concept is the possibility of a radical resection, if the patient is operable [2]. As a rule, in stage I to IIIA, a surgical approach, if necessary with (neo)adjuvant chemotherapy, should be pursued. The 5-year survival rate corresponding to tumor stages ranges from 24 to 73% in this group of patients (Fig. 1) [2].

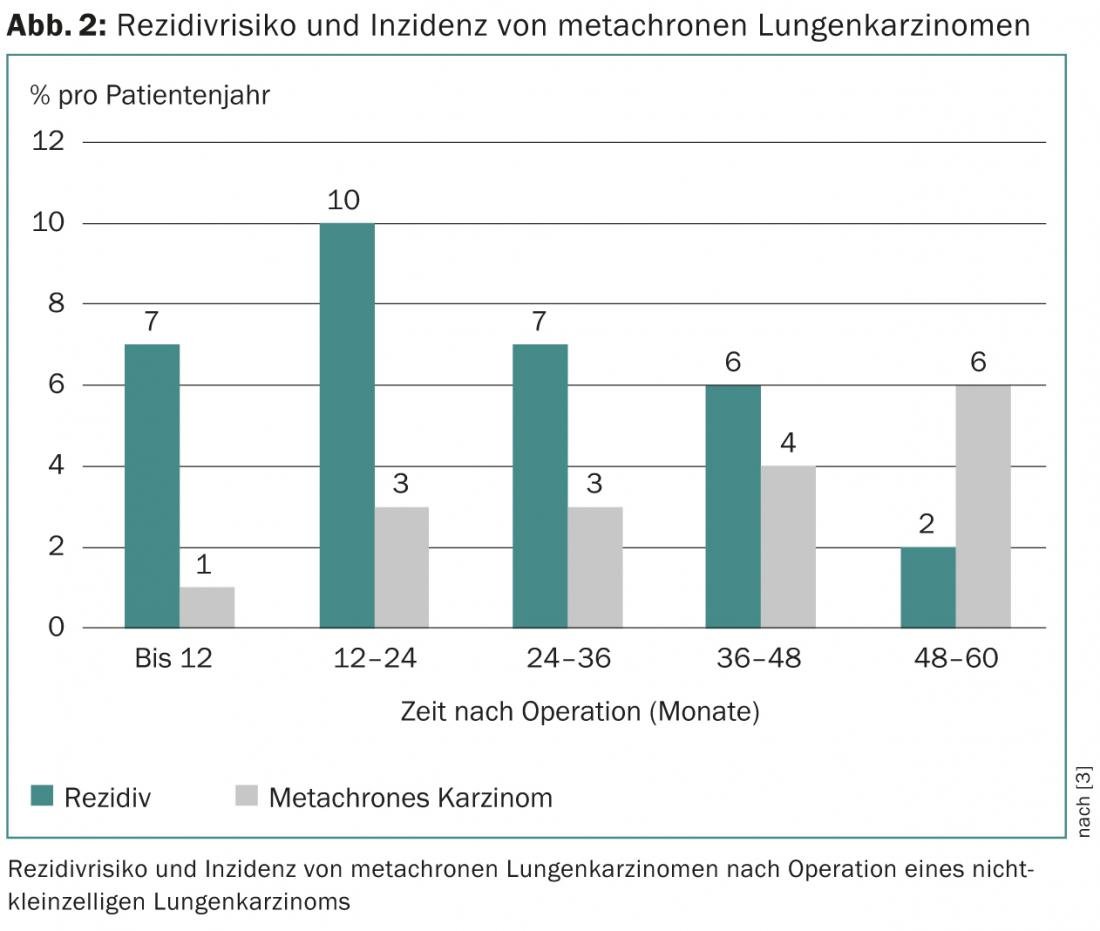

Recurrence and metachronous carcinoma

The patient’s probability of survival depends on the tumor stage and the corresponding risk of recurrence. The latter increases to a maximum of 10% per year in the first two years after surgery and then slowly decreases again [3]. Cumulatively, 5-71% of all patients – depending on the initial tumor stage – suffer a recurrence, which in half of the cases occurs in the first two years postoperatively [4–7]. In addition, the occurrence of a metachronous carcinoma (“second primary carcinoma”), the risk of which increases steadily with time after surgery, must be distinguished from recurrence (Fig. 2).

Pros and cons of postoperative follow-up care

In view of the recurrence rate and the risk of metachronous carcinoma, it seems reasonable that these neoplasms can be detected early, i.e. at an asymptomatic stage, by structured post therapy surveillance – provided that renewed therapeutic intervention improves survival and quality of life.

Unfortunately, data regarding the value of postoperative follow-up after operated lung carcinoma are rather sparse and sometimes even contradictory. Since the surgery rate for locoregional recurrences is relatively low at 1-4%, no reliable statements can be made about the benefit of tumor follow-up [7]. Randomized controlled trials that have addressed this question are completely lacking. In a prospective, nonrandomized study, median survival was shown to be significantly longer in asymptomatic than in symptomatic recurrences [6]. In contrast, other authors have not found any effect of structured follow-up on survival or quality of life [8–10]. However, in a recent meta-analysis, despite the heterogeneous follow-up programs used in the included studies, structured follow-up showed that recurrences were more likely to be diagnosed in an asymptomatic study, significantly improving the probability of survival (hazard ratio 0.61, 95% confidence interval 0.50-0.74, p<0.01) [11]. However, the cost-effectiveness of regular postoperative follow-up, at approximately 90 000 Swiss francs per patient-year, should be considered [12, 13].

Unfortunately, neither the initial tumor stage nor the resectability of locoregional recurrence have been considered in previous studies addressing this issue. For this reason, various parties have called for an “individualized” follow-up program, i.e., one that is adapted to the tumor stage and health status [7].

Methods of postoperative follow-up

In principle, various modalities can be used in postoperative follow-up, individually or in combination (X-ray, computed tomography, positron emission tomography [PET], bronchoscopy, laboratory and clinical examination).

However, the heterogeneous nature of follow-up programs makes a conclusive assessment of their utility and cost-effectiveness difficult. As mentioned earlier, randomized trials comparing the different strategies in operated patients with NSCLC are lacking. Thus, it is currently unclear which follow-up method should be used and at what intervals. In this regard, the recommendations and expert opinions from the various professional societies are also inconsistent. On the other hand, it is generally agreed that regular follow-up examinations are useful (Tab. 1). Regarding the method, computed tomography seems to be the method of choice due to its cost-effectiveness, relatively low radiation exposure and relatively good sensitivity (62-100%), although PET/CT is superior in terms of sensitivity (97-100%) [7].

Another unresolved question: who should perform the postoperative follow-up visits? After all, in a retrospective study of 245 patients, there is evidence that there is no significant difference in terms of mortality when follow-up is performed by the treating surgical team or by a primary care physician [14]. It even seems reasonable, according to a British study, that specifically trained nurses can provide follow-up comparable to physicians in terms of patient satisfaction and cost [15]. However, the effect on mortality rates was not considered in this study.

Conclusion

Although clear data regarding the benefit of structured postoperative follow-up in NSCLC are lacking, a follow-up program seems to be recommended if a curative therapeutic approach can be offered. Since the frequency of recurrence is significantly higher in the first two postoperative years than in the subsequent years, follow-up examinations should be performed more closely (e.g., every 3-6 months), especially during this period. At the same time, however, it should be noted that the number of computed tomography scans, especially in younger patients, must be taken into account due to radiation exposure. Nevertheless, computed tomography appears to be the method of choice in tumor follow-up because of its high sensitivity and relatively low radiation exposure.

Conclusion for practice

- The risk of recurrence after curatively operated non-small cell lung cancer is highest in the first two postoperative years (7-10%/year).

- Early detection of recurrence at an asymptomatic stage is likely to reduce mortality if a curative therapeutic approach can be offered. However, the data situation in this respect is insufficient.

- There are no randomized trials that have compared different follow-up programs (modality, timing, and interval) in terms of their benefits and cost-effectiveness. Therefore, recommendations from different professional societies are heterogeneous in this regard.

- Because of its high sensitivity and relatively low radiation exposure, CT is currently the method of choice for detecting early recurrence.

Daniel Franzen, MD

Literature:

- Eur Respir Rev 2013; 22: 382-404.

- Chest 2009; 136: 260-271.

- J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2013; 145: 75-81; discussion 81-72.

- Cancer Res 1995; 55: 51-56.

- Ann Thorac Surg 1984; 38: 331-338.

- Ann Thorac Surg 2000; 70: 1185-1190.

- Ann Thorac Surg 2013; 95: 1112-1121.

- Chest 1999; 115: 1494-1499.

- J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1996; 112: 356-363.

- Ann Surg 1995; 222: 700-710.

- J Thorac Oncol 2011; 6: 1993-2004.

- Ann Thorac Surg 1995; 60: 1563-1570; discussion 1570-1562.

- Eur Respir J 2002; 19: 464-468.

- Ann Thorac Surg 2000; 69: 1696-1700.

- BMJ 2002; 325: 1145.

- J Clin Oncol 2004; 22: 330-353.

- Ann Oncol 2010; 21 Suppl 5: v103-115.

- Chest 2007; 132: 355S-367S.

- Radiology 2000; 215 Suppl: 1363-1372.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Guidelines in Oncology: Non-Small Cell Carcinoma. Available at: www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/PDF/nscl.pdf

InFo Oncology & Hematology 2013; 1(1): 22-24.