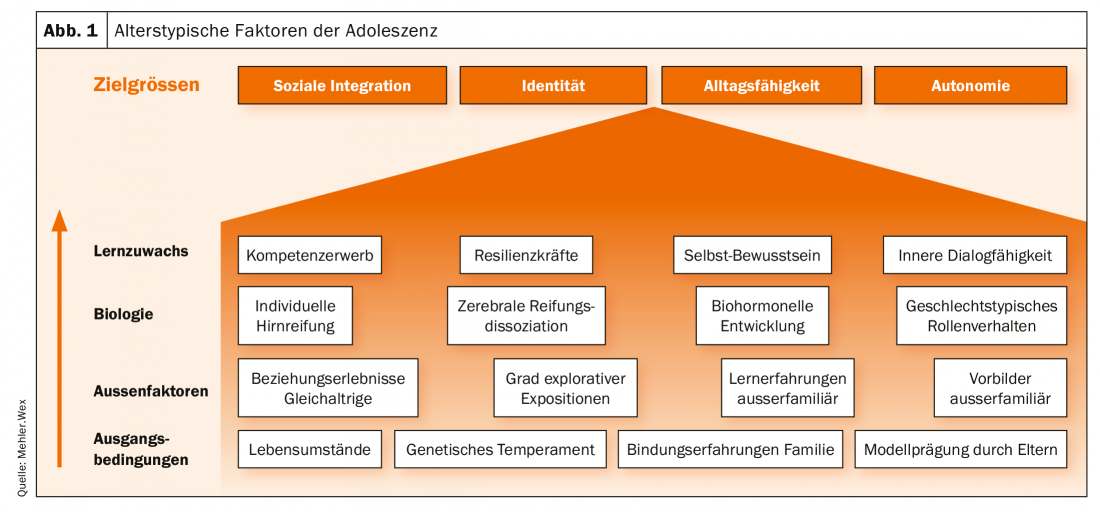

Finding an identity, social integration, autonomy development and finding a career are just a few of the issues that young people have to deal with in their transition to adulthood. Accordingly, holistic support is required.

Overall, a comprehensive reorganization of cortical structures and circuits takes place during adolescence. In this context, “the gut matures faster than the head”: the prefrontal cortex responsible for action planning and rational decision-making matures last, whereas the emotion-associated limbic and reward systems mature earlier [1]. This so-called cerebral dissociation of maturation, which is typical for adolescence, paves the way for the impulsiveness and mood lability typical of adolescence. This is matched by the increase in attention-promoting, higher-frequency alpha- and beta-wave activity in the electroencephalogram, whereas slower frequencies predominate prepubertally [2]. In addition, the amygdala is more active, equally responsible for more impulsive behavior. In reward-dependent situations, the nucleus accumbens is particularly activated, which is attributed to the youth-typical “sensation seeking”, the search for the kick [3]. The cerebral dissociation of maturation is a secondary reason why young people are better reached by emotional means than by rational arguments.

The remodeling processes in the sensorimotor cortex promote the increasingly developing empathy and theory-of-mind abilities, the ability to put oneself in someone’s shoes, resulting in increased emotional vulnerability. Particularly in girls, the hormonal situation must also be taken into account in the context of sensitivity: rising estrogen levels during puberty cause an increased susceptibility to stress. Coupled with the usually more intraverted nature, this creates an additional risk for psychological stress. A multi-layered interplay of various maturation processes, central nervous and hormonal, still interacting with external life factors and life-historical developmental tasks [4]: According to the model of activity-driven neuroplasticity, the brain matures in response to the demands placed on it or falls behind if exploration is avoided [5]. Thus, a primary biological maturation retardation paves the way for psychological stress, just as a primary psychological stress paves the way for a biological maturation retardation.

Developmental psychopharmacology is equally related to brain maturation processes, and therefore, if medications are used, it is imperative that they be considered: Pharmacodynamics (desired or undesired drug effects on the body) depend on receptor profiles and neurotransmission processes; however, the noradrenergic and dopaminergic systems are not mature until the late twenties! Pharmacokinetics (absorption, distribution, metabolism, and elimination of a drug by the organism) is based on factors that are also maturation-dependent, such as cytochrome P450 functions, body tissue composition, renal activity, or protein binding [6]. In summary, a maturing organism is not a younger adult edition across the board [7]. The expert group on therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) of the Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Neuropsychopharmakologie und Pharmakopsychiatrie (AGNP) therefore recommends general TDM for minors as a routine component of medical care for optimized dose adjustment [8].

Psychosocial tasks of adolescence

Neuropsychologically, the focus of adolescence is on identity development. Here, innate temperament factors interact with attachment experiences and life circumstances. Mothers are primarily models for attachment and trust skills, fathers promote explorative interest and self-confidence. Insecure attachment experiences can be reflected accordingly in the form of independence, dependency, emotional instability, etc.

Basically, self-awareness is an indispensable prerequisite for being able to perceive one’s own needs and attitude and to match them with new experiences. Often, however, one’s own feelings and impulses are pushed away in favor of external functionality or out of insecurity, instead of being consciously reflected upon. If there is also a lack of confidants and deeper communicative exchange, the result is an inner overload that often seeks its outlet in the mood and behavioral fluctuations common to adolescence. If these miscompensation strategies between complete adaptation and aggressive dissociation cannot be resolved in the long term, significant psychological stress will result in the medium term. These further block age-appropriate further development, which in turn increases mental stress, with the result that identity and competence development processes stagnate.

A particular hurdle is the tightrope walk between individuation and integration: On the one hand, social integration is necessary, which requires adaptability and reciprocity; on the other hand, ego-finding and individuation are to be classified as processes of demarcation. If the focus is only on individualization, no social embedding can take place; if, on the other hand, the desire for social integration is overpowering, a disproportionately strong orientation to the outside takes place with a facadarly high level of functioning, but a vanished self. Sexual orientation issues as well as gender insecurity can be a symptom of a search for identity, or, in the latter case, an outlet for unresolved stress. In the new physical identity the (er)-solution is hoped for. Of course, this model does not apply to every person with gender dysphoria, but especially in adolescents it is important to carefully clarify deeper backgrounds in child and adolescent psychiatry before starting hormonal treatment. However, sexual maturation is always a vulnerable aspect of development. Gender signs are more visible in girls than in boys, and therefore puberty is often accompanied by significant insecurities. Precocious girls are at significantly increased risk for mental illness. In addition, the first partnership and intimate relationship experiences are made during adolescence and must be processed.

Autonomy development involves the entire family and is mutually shaped by the individuals involved. In anxious families, there is often a lower level of exploratory experience with few resources of self-efficacious experience, which is associated with lower flexibility and problem-solving skills at the behavioral level. Fears of change with feelings of guilt and obligation as well as social phobic parts and lack of self-confidence are in the foreground. Family situations with parentification conditions also complicate the detachment process. Conversely, more expansive adolescents also seek separation from parental care very abruptly. From the parents’ point of view, massive insecurities caused by countless parenting guides as well as the weakening of family ties are leading to an increasingly intrusive parenting style, i.e. parents today involve themselves much more intensively and for a longer period of their lives than in the past in the concerns of their children, with tendencies to hold on or care for them into adulthood [9]. In this context, considerably more prolonged deliberation processes are cultivated in the entire family in view of the upcoming, unknown stage of life, accompanied by far-reaching decisions about school and career perspectives. In this context, it is not only the deeply internalized demand for performance, especially among sensitive individuals, that is an unsettling factor in the current generation of young people, but also the agony of choosing from a boundless number of career options as well as the mixture of inflated expectations of a “dream job,” possibly (anticipated) parental expectations (e.g., with regard to fulfilling an existing status or family tradition), and the internalized sense of duty on the part of the parents to make the child cooperative rather than independent. (Anticipated) parental expectations (e.g., with regard to the fulfillment of an existing status or a family tradition) and the parents’ internalized sense of duty to bring the child onto the right path in a cooperative rather than independent manner and with only background support. Personal development opportunities, social reputation, social status, identification and life satisfaction seem to depend exclusively on the profession. The transition from guided schooling, which is not debatable per se, to self-selected student or practical work life can trigger strong self-doubt and feelings of being overwhelmed. As a result, young people on the threshold of working life therefore remain much longer in a phase of ruminative exploration, in short: they are treading water with regard to their future decisions [9]. If a first attempt is unsuccessful or if there is a dropout, this is often overvalued as a complete failure and a new attempt is not dared. This may also explain the failure of the attempt in Germany to shorten grammar school education by one year, in that the time gained was not, as politically intended, invested in an earlier academic or other professional career, but primarily for recreation or orientation.

The rapidly growing influence of the media and the accompanying accelerated lifestyle – permanent presence online, distraction through permanent multitasking, weakening of direct communication skills, sleep disturbances, secondary attention deficits in everyday care – means for some people cutbacks in self-organization and coping with everyday life. As social media suggest comprehensive perfection (attractiveness, originality, self-confidence, social and professional success) as a matter of course via supposedly real role models, life management per se has become a challenging competitive event. I am what I can show. Activities and contacts via social networks are generally no substitute for real life, but in the medium term provide a breeding ground for loneliness, difficulties with demarcation, defenselessness, demands for perfectionism, and diminished self-esteem.

To take full account of the study situation, statistically particularly relevant risk factors for mental illness in young people have emerged, in part self-explanatory, as low social status, parenting difficulties, chronically ill close caregivers (especially depressed mothers), intrafamily conflicts, insecure parent-child relationships, and severe stressful events. Low social and/or problem-solving skills as well as weak resilience and coping strategies and anxious-insecure or impulsive disposition aggravate the risk (Fig. 1).

Maturation as a crisis

There is no separate digit for adolescent crisis in ICD-10. It is understood as the unsuccessful overcoming of the challenges of adolescence, related to the social-cultural environment and the age of the person concerned [10]. From the Greek, “crisis” means a “decisive turn,” with no negative connotation. However, this “turn” can be dramatically reflected in the family microcosm with extreme mood lability, drastic changes in communication, free-floating basic attitudes, and disconcerting behavioral experiments. 30-50% of adolescents show abnormalities in personality testing, but this usually normalizes by adulthood. 15-20% of pubertal turbulence results in more serious disorders [11].

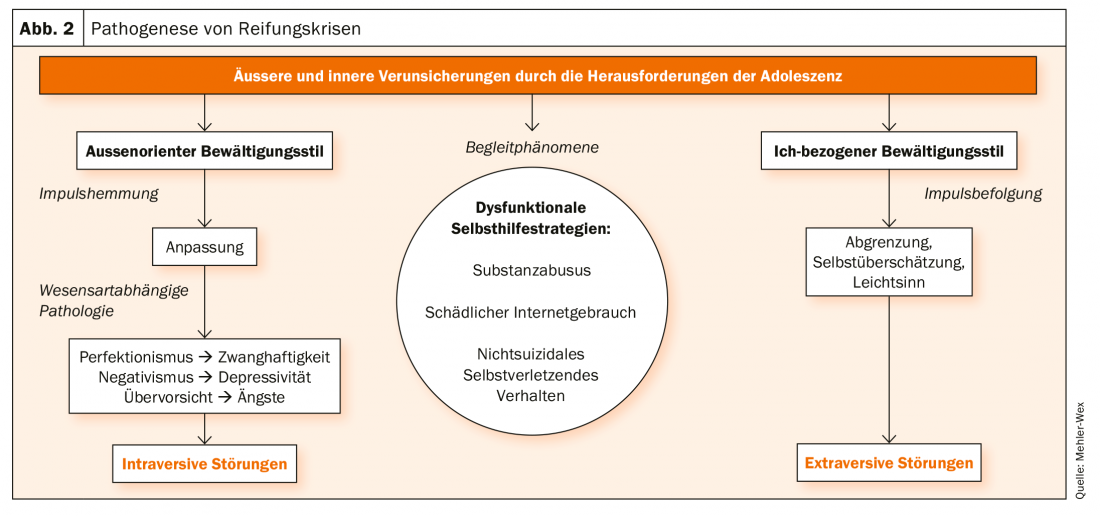

From clinical experience, it is apparent that many of the Axis I disorders in adolescents are based on being overwhelmed by life history developmental tasks. This means that a primary maturation crisis seeks secondary “valves” in the form of psychiatric clinical pictures. These in turn manifest themselves in a form close to the individual’s nature: Patients with an overprotective environment tend to anxiety disorders, perfectionistically inclined to compulsions or anorexia, etc. Intraverted young people tend to over-adapt and neglect their own impulses and emotions, body-related decision-making chains are interrupted, they cannot separate themselves, struggle to maintain a socially desirable facade. In them the risk of a corresponding internalizing disorder increases, such as anxiety (social phobia at this age: about 5%), depression (3-10%), compulsion, anorexia (up to 1%). Others, in their insecurity, tend to expansive dissociation, which can lead to clinical pictures with impulsive behavioral disorders. Sometimes, autism spectrum disorders (Asperger’s syndrome, high-functioning autism) that have been laid out just in the socially demanding adolescence also manifest themselves. During the course, personality development disorders can sometimes be discovered, but at this early stage, with its many possibilities for change, they can still be well addressed therapeutically. Not only expansive, but also internalizing patients use dysfunctional coping strategies: In addition to the above-mentioned diagnoses or accompanying them, we often find harmful substance use, internet abuse or self-injurious behavior in adolescent psychiatry.

Whether a maturation crisis is still physiological or pathological is clearly answered at the latest when the age-appropriate daily routine and/or social integration no longer succeed. Then, the need for therapy usually becomes apparent to the affected persons themselves. Figure 2 shows the pathogenesis of maturation crises.

Self-healing

In case of insecurity and perceived loss of function and stability, coping strategies are required; whereby distress often initially leads to dysfunctional paths. Substance abuse in adolescence is sometimes a form of self-medication. Tension relief, increased activity, disinhibited social contact have a reinforcing effect and may induce harmful use. It is not only disorders characterized by impulsivity that are affected, such as social behavior disorders, borderline personality disorder, bulimia nervosa or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder – in the context of which, by the way, the risk of substance abuse is doubled in comparison to treated ADHD patients in the absence of treatment. Intraversive patients with depression or anxiety disorders also tend to abuse substances to a similar extent [12].

Up to 13% of 19-year-olds in Germany maintain a harmful use of alcohol (15% of boys and 7% of girls) and are therefore unfortunately ahead in the European comparison [13]. About 10% use illicit drugs (about 7.3% THC) [14]. Frequent substance abuse has a much more neurotoxic effect at this stage of development than on the mature brain, resulting in permanent deficits with ADHD-like phenomena such as concentration and performance difficulties, lack of drive and structure. Social cognitive developmental steps such as taking responsibility, problem management and real social skills are inhibited; sometimes traumatizing experiences are encouraged under the influence of substances – a vicious circle.

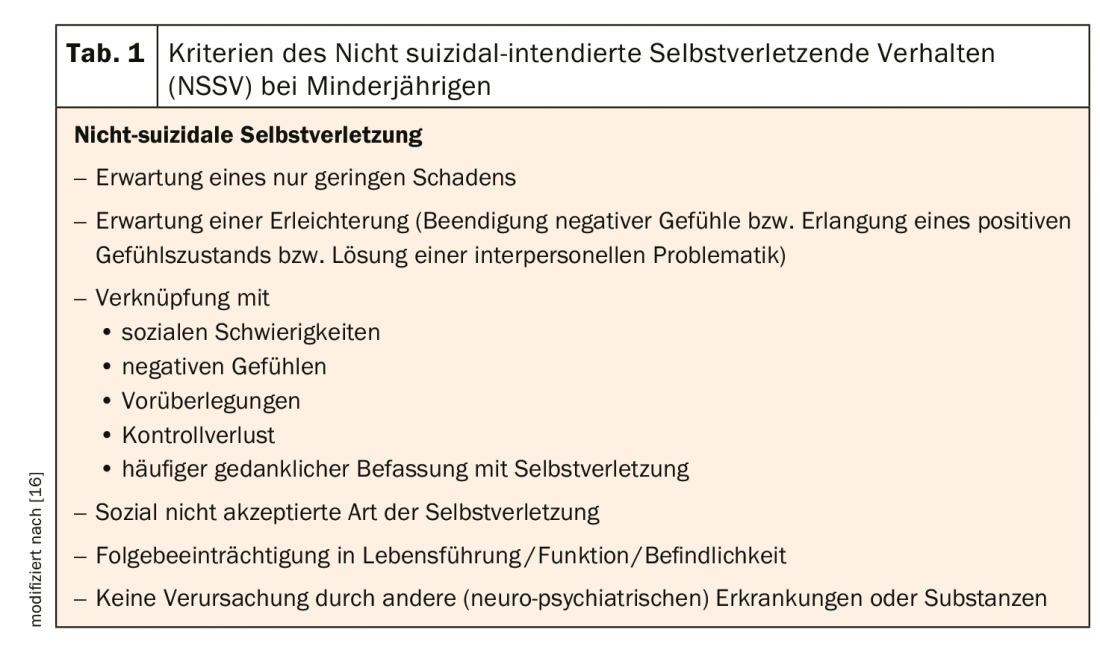

Autoaggressive behavior can be an outlet for self-hatred, insensitivity, excessive demands, self-punishment, tension, inner pressure. In school samples worldwide for 8-26%, in Germany unfortunately even for 25-35% at least one “trial use” of self-injurious behavior is reported, 12% remain repetitive, most often 15- to 16-year-olds [15]. While in adults autoaggressiveness is associated with borderline disorder in 80% of cases, so-called non-suicidal-intending self-injurious behavior (NSSV) occurs in minors as an independent phenomenon distributed across almost all diagnostic groups. The reasons for this could be developmental biological characteristics: On the one hand, the already discussed cerebral dissociation of maturation promotes impulsive, unreflected behaviors, and on the other hand, young people have a biologically higher threshold for pain perception [16]. Criteria of the NSSV are shown in table 1 .

The virtual world offers another grateful field for retreating from real-life demands or creating a wish-fulfilling ego. In Germany, prevalence estimates for harmful Internet use are up to 4.8% [17]; boys are more frequently affected than girls (5.2% and 3.8%, respectively), especially with regard to video games – particularly among ADHD sufferers – while girls are more inclined toward social media. Criteria of harmful Internet use are summarized in Table 2. The early social pressure to show oneself in the media and to be omnipresent in communication is a burden and tempts people to unrealistic ideals of perfectionism. For attention seeking, boundaries are also crossed; for example, more than half of the self-presenting depictions of adolescents in Internet forums are said to show content that is harmful to health or promotes risk (e.g., descriptions of sexual activity, self-harm, alcohol, etc). In addition, increased Internet consumption per se leads to withdrawal, everyday neglect, reduced sleep quality, mnestic disorders and possibly – in the case of violent games – aggression triggering [18]. However, a real “addiction” is often not present; here, educational work is also necessary with parents regarding the appropriate use of new media. For most patients, the Internet seems to play more of a role as an element of employment, which loses importance once a daily routine is restored. Exception: an actual gambling addiction practiced on the Internet.

Therapeutic relationship building in adolescence.

For trust building, the feeling of acceptance by the therapist is extremely important for the young patient. Tolerance and patience as well as recognition of the patient’s autonomy aspirations – within a socially acceptable framework – are central prerequisites for developing alternative and more differentiated ways of seeing and behaving out of the therapeutic bond. Avoidance, procrastination, and distrust often play a role, and in therapeutic teams, manipulative or splitting attempts. Immediate, solution-oriented addressing of such an observation in the sense of benevolent attention contributes to transparency and to mirroring. Negative transferences such as parental projections into the therapist are to be reflected upon vigilantly, especially since professional follow-up care is sometimes necessary especially in the face of missed developmental steps and regressive tendencies and can represent a new experience. Follow-up questions and summaries in the patient’s own words of what the patient has said emphasize acceptance in direct dialogue.

Transparency is therefore another essential aspect of working with young people. Goals must be defined precisely and jointly, reviewed again and again, and adjusted if necessary. By taking exact stock and concretely naming stage goals and priorities from the patient’s point of view, the therapy program can be worked out and explained to the patient. It is of no use if only the therapist anticipates what might be necessary for the patient, then the common denominator is missing and misunderstandings or irritations are pre-programmed. A lively, emotionally authentic exchange also contributes to the theme of transparency. Mirroring emotions to a patient (“Your behavior today made me angry”) underscores a therapist’s personal involvement, interest, and possibly unconscious external impact, and can initiate rethinking (“Do you know how others get angry with you in similar situations?”, “Do you understand why I feel that way?”, “Could there have been other possible behaviors?”, etc.).

Reliability and coherent-consistent, comprehensible action (“containment”) on the part of the therapist are further important factors in the interaction. Through inquiry and explanation, therapeutic (re)actions can be embedded in an understanding of a consistent model of illness. A pragmatic approach that is close to everyday life has a more winning effect on young people. Descriptive procedures such as schema therapy relatively quickly reveal intrapsychically superior, behaviorally controlling patterns of perception and attitude (in this case, “parenting modes”) versus neglected needs (“child modes”), as well as the dysfunctional coping strategies developed to bridge these discrepancies. Well-understandable and structured methods have an inviting effect and improve compliance.

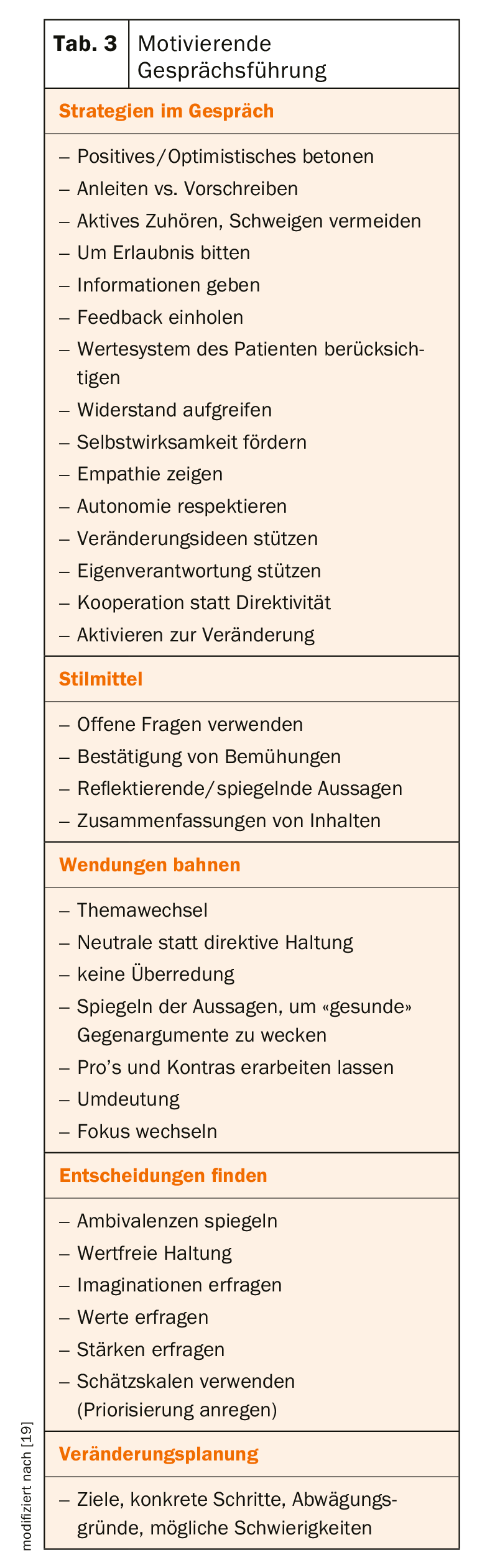

In principle, a motivating approach is recommended (Tab. 3), which is characterized by a friendly approach, attentive interest and (appropriate) vibrancy or empathy. Similarities in terms of general interests or conversational style (e.g. similar humor, dialect) make it easier to get started; unexpected understanding (“It’s okay if you don’t answer all the questions”) or getting involved in an initially less psychologically captivating goal project (“How about we start by figuring out how we can build up a daily structure again?”) can also break the ice.

Acceptance does not contradict a therapeutic attitude that must interpret and sometimes limit. Too permissive behavior of the therapist would be out of touch with reality, while directive behavior could trigger regression and stagnation (“The therapist works, the patient does not”). Therefore, goal-oriented progress, demonstration of real feasibility and load testing are decisive components. The following always applies: The patient himself works out his own path; it is up to the therapist to ensure a trusting, safe framework with appropriate impulse setting.

Therapeutic work with adolescents should always be resource-oriented. Adjuvant creative therapeutic methods can succeed in finding insights and new approaches to solutions as well as access to one’s own emotionality on a symbolic level. If the procedure itself is able to arouse interest and curiosity in the patient, an unbiased entry into the therapeutic work can also be supported here. In the most favorable case, psycho- and creative-therapeutic work intertwine, in that the results of one therapy are deepened and further developed in the other.

Holistic therapy

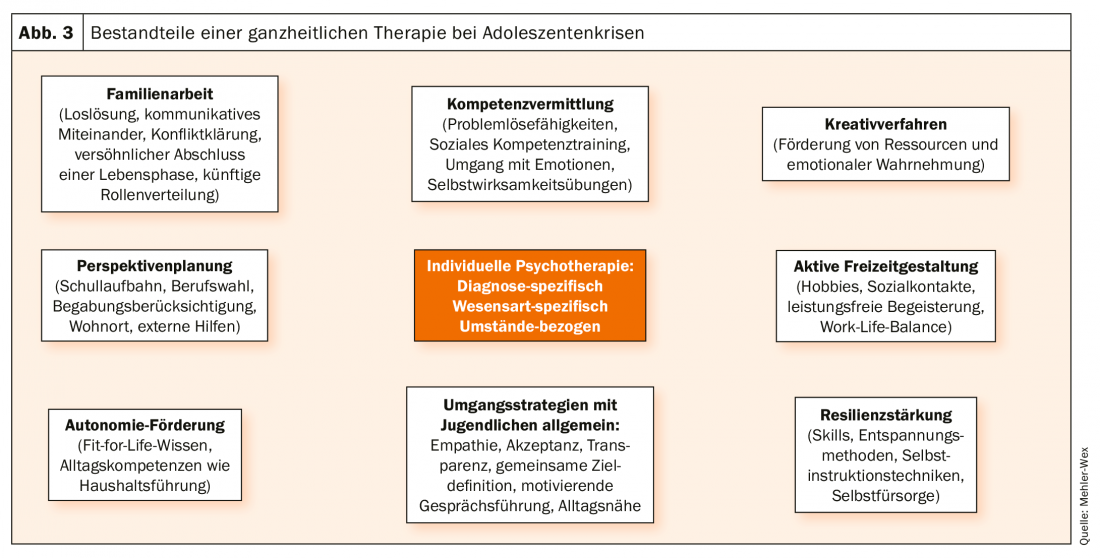

Psychiatric diagnoses in adolescence are often seen as an “outlet” for an underlying maturational crisis. In this respect, in addition to a disorder-specific approach, a holistic view of all essential aspects of the young person’s life is indicated.

Psychological stress delays personality development and vice versa. Often, identity boundaries are highly permeable due to (literally) a lack of self-awareness. On the ground of general uncertainty, dysfunctional basic beliefs, misperceptions and correspondingly dysfunctional coping strategies emerge. Individual psychotherapy should set itself the task of making evaluation styles and perception patterns more differentiated. Therapy strategies on mindfulness as well as body-supported methods open up access to emotional self-awareness and pave the way for a more positive body and thus self-acceptance. Irrespective of the diagnosis, there are almost always reservations about the external appearance by which adolescents believe they have to define themselves, especially in the media world. Body image work is not only a helpful measure for patients with eating disorders. Gender-specific groups can help with orientation into one’s gender role.

In order to establish integrative empowerment in addition to identity delineation, social skills training in an age-homogeneous group is often recommended. In the inpatient setting, adolescents benefit in the long term from an adolescent psychiatric setting as a protected practice environment per se. Milieu therapy, which is common in child and adolescent psychiatry with the help of a multiprofessional nursing and education service, can provide positive, stable relationship experiences through a reference caregiver system, ensure coaching for social and everyday skills with a high degree of realism in everyday ward life, and promote the transfer of therapeutic content into everyday life. Role-playing, e.g. in therapeutic theater or experiential group activities, also consolidate the ability to integrate and work in a team.

Everyday functioning and resilience with appropriate problem and conflict resolution strategies represent key core competencies to reinforce self-efficacy and autonomy. It is important to gently introduce them to the challenges of life again. In the inpatient setting, this can take place through external training that follows on from the internal clinic training, and/or through occupational therapy, which not only promotes the ability to concentrate and persevere, but also prepares the patient for coping with typical occupational and training challenges, such as the systematic solution of problems, self-organization, obtaining help, integration into a group of co-workers. and much more. It is important not only to view life in terms of performance, but also to consciously allow oneself purpose-free leisure activities in order to achieve a “work-life balance”. In the context of high performance orientation v.a. internalizing patients, special attention must be paid to the topic of “self-care” in order to allow room for the needs of the inner child in the face of external high functioning. Thus, stimulation for active leisure time activities without performance demands should also find a place in the holistic view. In an inpatient setting, internal offerings in the area of sports or creativity can offer a taste of what’s to come, while cooperations with clubs allow for a reality-based implementation. The new or rediscovered hobby should be incorporated into everyday life as a fixed program item and resource.

The development of autonomy with detachment from the parental home costs a lot of energy for all involved, even if the process is “physiological”. The attempts at demarcation are accompanied by irritating communication difficulties, misunderstandings and impaired trust, or they fail to materialize and the adolescent remains in age-inappropriate dependency. Therefore, in individual psychotherapy, parents and their personality-forming views and behaviors are also very much in focus at this age. Which of these imprints are helpful, which are inhibiting, how can the demarcation succeed, how can one’s own be consolidated – these contents are essential for the consolidation of an autonomy-capable personality.

But the systemic view is also worthwhile; even young adults sometimes still benefit from family therapy with their parents. Emotional detachment may also be hindered by issues of past disappointment, blame, lack of attention, paternalism, or lack of trust. Then a therapeutically accompanied clarification or at least open naming of the conflict and its meaning with the family is an essential step to bring about a solution, an understanding or at least a transparency, with which the view can then be constructively directed forward again. Sometimes, even for the upcoming new phase of life, concrete planning aids for the further distribution of roles as well as responsibilities in the sense of a constructive, benevolent cooperation agreement are very clarifying and encouraging. An external mediator can make a good contribution to objectification and structuring. In very stuck interaction patterns, we have found that classical family therapy can be greatly enriched by moving therapeutic sessions into a creative therapeutic milieu to offer new experiential qualities and communication techniques. In a symbolic, non-verbal way, a completely different clarity can often be achieved than through the well known, cognitively oriented mode of conversation.

As adolescent patients are in the haze of graduating from high school, perspective planning is a very important component of therapy. Decision-making difficulties often exist due to unrealistically inflated expectations of a professional superlative (always happy-making, exciting, fulfilling, lucrative activity). A “misstep” does not seem to be allowed here. Possible misconceptions or interactions with the parental home regarding future course settings are therefore, if necessary, the decisive subject of psychotherapy. A realistically assessed aptitude is an indispensable building block in concrete career choices, so if there is any doubt, performance testing should always be conducted to differentiate aptitudes and feasibilities via the aptitude profile. Employment offices and social counseling services are appropriate places to start to address career exploration. Job application training and, if necessary, vocational orientation internships are experienced as helpful. In the inpatient setting, further possibilities open up through individual socio-pedagogical support (e.g. involvement of public authorities, help plan discussions, placement with cooperating companies, for students, if necessary, visits to external schools, boarding school counseling, support with changes of school or place of residence). In our clinic, a seminar program accompanying therapy has also proven successful in teaching everyday skills and household management (incl. knowledge of bureaucracy and finances, cooking course, cleaning skills, etc.).

Overall, it is not sufficient for adolescents with psychiatric diagnoses to focus solely on the disorder-specific therapy of the primary diagnosis; rather, the accompanying issues that are intrinsic to the life stage of the 18-year-olds require careful consideration in the sense of a holistic treatment concept (Fig. 3).

Summary

Adolescence is accompanied by numerous challenges – finding identity, social integration, autonomy development, finding a career. In the context of maturation, crises with loss of everyday functionality and manifestation of psychiatric illnesses may occur, which must be treated holistically, not only syndrome-specifically, but in the sense of causal therapy. Helpful aspects in the treatment are a benevolent, accepting attitude of the therapist, motivating conversation, resource orientation, closeness to everyday life, the inclusion of non-verbal methods as well as the mediation of experiences of self-efficacy. In clinical care, adolescent-specialized settings offer the opportunity to create a motivating practice environment through patient age homogeneity. Adolescent psychiatry is a cross-age and thus interdisciplinary adolescent and adult psychiatric topic that addresses young people who have not yet found their place – socially and professionally – and their self. The focus here is on development work in order to be able to continue on the path of life after a crisis-ridden phase in life, matured and strengthened in terms of competence.

Literature:

- Konrad K, Firk Ch, Uhlhaas PJ: (2013) Brain development in adolescence. Deutsches Ärzteblatt 110 (25), 425-431.

- Uhlhaas PJ, Roux F, Singer W, et al: (2009) The development of neural synchrony reflects late maturation and restructuring of functional networks in humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 106, 9866-9871.

- Spitzer M: (2009) On the neurobiology of adolescence. In: Fegert JM, Streeck-Fischer A, Freyberger HJ (eds.) Adolescent psychiatry. Stuttgart New York: Schattauer, 133-141.

- Braus DF: (2014) Developmental psychobiology. In: Braus DF: A look into the brain. 3rd ed., Stuttgart: Thieme, 25-33.

- Teuchert-Nodt G, Lehmann K: (2008) Developmental neuroanatomy. In: Herpertz-Dahlmann B, Resch F, Schulte-Markwort M, Warnke A (eds.) Developmental psychiatry. 2nd edition, Stuttgart: Schattauer, 22-40.

- Klampfl K, Mehler-Wex C, Warnke A, Gerlach M: (2016) Developmental psychopharmacology. in Gerlach M, Mehler-Wex C, Walitza S, Warnke A, Wewetzer Ch. (eds.) Neuro-/Psychopharmaka im Kindes- und Jugendalter. 3rd ed., Berlin Heidelberg: Springer, 71-80.

- Gerlach M, Egberts K, Dang SY, et al: Therapeutic drug monitoring as a measure of proactive pharmacovigilance in child and adolescent psychiatry. Review Expert Opinion Drug Safety (2016) 15(11): 1477-1482.

- Hiemke C, Baumann P, Bergemann N, et al: (2011) AGNP Consensus Guidelines for Therapeutic Drug Monitoring in Psychiatry: Update 2011. Pharmacopsychiatry, 44, 195-235.

- Seiffge-Krenke I, Escher FJ: (2017) Delayed identity development, family relationships, and psychopathology: correlations in healthy and clinically abnormal adolescents. Zeitschr Kinder- Jugendpsychiatrie 46(3), 206-217.

- Streeck-Fischer A, Fegert JM, Freyberger HJ: (2009) Do adolescent crises exist? In: Fegert JM, Streeck-Fischer A, Freyberger HJ (eds.): Adolescent psychiatry. Stuttgart New York: Schattauer, 183-189.

- Remschmidt H: (2013) Adolescence – mental health and mental illness. Deutsches Ärzteblatt 220 (25): 423f.

- Schepker R, Barnow S, Fegert JM: (2009) Addictive disorders in adolescents and young adults. In: Fegert JM, Streeck-Fischer A, Freyberger HJ (eds.): Adolescent psychiatry. Stuttgart New York: Schattauer, 231-240.

- Bundeszentrale für gesundheitliche Aufklärung (2015) Der Alkoholkonsum Jugendlicher und junger Erwachsener in Deutschland 2014. www.bzga.de/forschung/studienuntersuchungen/studien/suchtpraevention/?=92

- Piontek D, Orth B, Kraus L: (2017) Illegal drugs – facts and figures. in: Deutsche Hauptstelle für Suchtfragen (ed.), Jahrbuch Sucht 17, Lengerich: Pabst, 107-112.

- Plener PP, Kaess M, Schmahl Ch, et al: (2018) Non-suicidal self-injurious behavior in adolescence. Deutsches Ärzteblatt 115(3): 23-30.

- Plener P, Kapusta N, Brunner R, Kaess M: (2014) Non-suicidal self-injurious behavior (NSSV) and suicidal behavior disorder (SVS) in DSM-5. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 42(6): 405-413.

- Wartberg L, Brunner R, Kriston L, et al: (2016) Psychopathological factors associated with problematic alcohol an internet use in a sample of adolescents in Germany. Psychiatry Research, 240, 272-277.

- Lehmkuhl G, Frölich J: (2013) New media and their consequences for children and adolescents. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 41(2): 83-86.

- Naar-King S, Suarez M: (2012) Motivational interviewing with adolescents and young adults. Weinheim Basel: Beltz.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2020; 18(3): 34-41.