It is known that the clinical picture of asthma can vary depending on gender. However, how exactly this affects the severity of symptoms, the function of large and small airways, inflammation and exacerbations has not yet been systematically investigated in large clinical studies. Dutch doctors have taken on this task.

It is already known that gender differences in asthma are multifactorial. Endogenous sex hormones are one of the most frequently studied factors; their fluctuations throughout life, such as during puberty, the menstrual cycle and menopause, play an important role in the increased prevalence and severity of asthma in adult women. In addition, male and female asthma patients may experience and report symptoms differently and be exposed to different social and environmental factors over the course of their lives. Therefore, gender inequality in asthma is very complex and can impact asthma severity, control and treatment. For this reason, it is important to learn more about the clinical differences between male and female asthma patients, as this could ultimately lead to optimization of precision asthma management. Previous studies on gender differences in asthma have not considered broad clinical characteristics or a wide range of asthma severity and have often not addressed the presence and extent of small airway dysfunction (SAD). Dr. Tessa M. Kole from the Department of Pulmonology and Tuberculosis at the University Medical Center Groningen in the Netherlands and her colleagues conducted a post-hoc study investigating gender differences in asthma control, lung function, inflammation and exacerbations [1]. The post-hoc analysis of the observational cohort study ATLANTIS (Assessment of Small Airways Involvement in Asthma) included asthma patients from nine countries with a follow-up period of one year, in which patients were characterized with measures of large and small airway function, questionnaires, inflammation and imaging. Participants were between 18 and 65 years old and were non-smokers, current smokers or former smokers who had quit smoking at least 12 months prior to enrollment in the study. Participants were characterized at baseline, including several questionnaires, asthma control tests (ACT) and pulmonary function tests such as fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO), body plethysmography, impulse oscillometry (IOS), multiple breath nitrogen washout (MBNW) and spirometry before and after bronchodilation. Airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR) was tested in a subgroup of patients using a methacholine provocation test. Blood samples were taken at baseline and during follow-up. Chest CT scans and sputum inductions were performed at selected sites at baseline. In addition, patients received telephone follow-up calls at 3 and 9 months after baseline and face-to-face follow-up visits at 6 and 12 months. Exacerbations were recorded throughout the study and were defined as a worsening of asthma that required systemic treatment with corticosteroids (≥3 days) and/or hospitalization and/or an emergency department visit. During the study, participants received routine medical care from their own healthcare provider. Medication changes were also recorded.

Women associated with poor asthma control and higher airway resistance

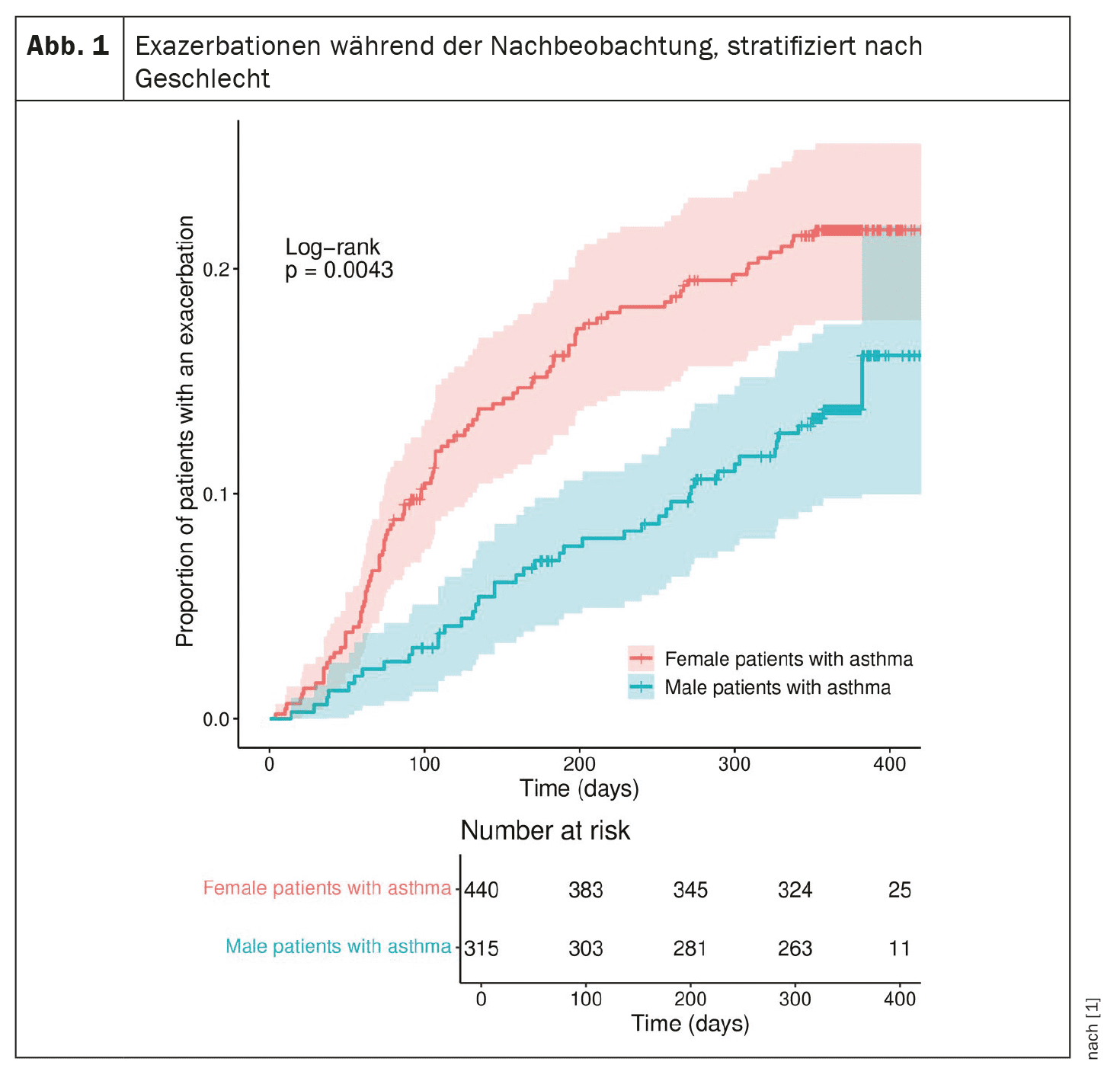

At the start of the study, a total of 773 patients were enrolled, of whom 450 (58%) were women. Male patients were younger at the time of diagnosis and more likely to have early asthma (onset before age 18), with a prevalence of 44% in male patients and 35% in female patients (p=0.017). They also had a significantly higher number of packyears (PY) than female patients (M: 6 PY vs. F: 3 PY; p<0.001). While the average body mass index (BMI) was not significantly different between male and female patients, women were more often in the “normal BMI” or “obese” category and male patients were more often in the “overweight” category. At baseline, female asthma patients were in higher GINA levels (p=0.042), had a higher Asthma Control Questionnaire score of 6 (F: 0.83; M: 0.66, p<0.001) and higher airway resistance, as indicated by uncorrected impulse oscillometry results (i.e. R5-R20: F: 0.06; M: 0.04 kPa/l/s, p=0.002). Male patients with asthma had more severe airway obstruction (forced expiratory volume in 1 s/forced vital capacity as % of prediction: F: 91.95%; M: 88.33%, p<0.01) and more frequent persistent airflow limitation (F: 27%; M: 39%, p<0.001). The number of neutrophils in the blood was significantly higher in female patients (p=0.014). In the Cox regression analysis, female gender was an independent predictor of exacerbations.

Female patients had worse results for all uncorrected IOS parameters, while the predicted FEV1 % was similar. These findings of higher resistance in the central and peripheral airways may indicate greater dysfunction of the large airways, and SAD and IOS may be more sensitive than FEV1, the authors explain. However, they point out that no suitable reference values are currently available. Alternatively, it could be speculated that the results of this study are merely based on an anatomical difference, namely dysanapsis. This could explain the differences between male and female asthma patients and not a clinically significant higher level of SAD.Apart from the significantly higher use of leukotriene modulators in females, the analyses performed did not show significant differences in prescribing patterns based on asthma severity between male and female asthma patients. According to Kole and colleagues, the fact that a significantly higher neutrophil count was found in the blood of female asthma patients was an expected result, as neutrophilic inflammation occurs mainly in patients with late and severe asthma, who are more often female. It is likely that the higher neutrophil count in the blood can be explained by the higher prevalence of obesity in women. Analysis of CT scans showed that male and female patients with asthma have similar airway wall thickness, as reflected by WA% and Pi10 (i.e. the average wall thickness for a hypothetical airway with a lumen circumference of 10 mm). Both airway lumens and airway walls, as represented by median wall and lumen area, were significantly smaller in female patients with asthma, but this is logical as women have smaller lungs overall and therefore smaller airways. Male current smokers and former smokers in ATLANTIS had a significantly higher number of PY, which was also associated with a higher VI 950 (voxel index at -950 Hounsfield units). Therefore, a certain overlap with COPD cannot be excluded in these subjects, although all subjects had a confirmed asthma diagnosis and a smoking history of >10 PY was an exclusion criterion in the ATLANTIS study.

Sex hormones could play a role

Women with asthma had a significantly higher risk of exacerbations (Fig. 1) and a more severe AHR than men. Sex hormones may play a role in both the increased risk of exacerbations and the more severe AHR in female patients. For example, it has been shown that AHR is increased during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle and that the risk of exacerbations increases during pregnancy. In contrast, androgens such as testosterone can actually reduce the incidence and symptoms of asthma. However, much is still unknown about the exact mechanisms by which sex hormones influence asthma pathogenesis, and more research is needed in this area, the authors write. Finally, contrary to previous findings, current smoking was not a significant predictor of exacerbations in this study, but this is likely due to the small number of smokers in this cohort. In addition to the higher risk of exacerbations, female patients have poorer disease control and possibly more small airway dysfunction than large airway dysfunction compared to male patients with asthma. In contrast, they have more severe airway obstruction and a higher prevalence of PAL (persistent airflow limitation, defined as FEV1/FVC below the lower limit of normal), the authors summarize. These results are significant as they underline the potential importance of precise treatment of asthma patients, in which gender may need to be considered separately.

Take-Home-Messages

- Gender has a significant influence on the clinical manifestation of asthma.

- The female sex is associated with more severe symptoms, impaired function of the large and small airways and bronchial hyperreactivity.

- Gender is a risk factor for exacerbations, regardless of the eosinophil level in the blood.

Literature:

- Kole TM, Muiser S, Kraft M, et al: Sex differences in asthma control, lung function and exacerbations: the ATLANTIS study. BMJ Open Respiratory Research 2024; 11: e002316; doi: 10.1136/bmjresp-2024-002316.

InFo PNEUMOLOGY & ALLERGOLOGY 2024; 6(4): 30-31