In a more somatically oriented general palliative care, mental illnesses are often perceived only as “side effects” and thus remain unrecognized. However, psychopharmacological interventions or psychotherapeutic processes can only be used if psychological symptoms are recognized as such. The concept of palliative care must thus be detached from its sole reference to end-of-life care and understood in a broader sense, especially for chronically mentally ill people. From this perspective, there are palliative phases that do not necessarily have to transition to a terminal phase as in palliative care oriented to somatic diseases. Professionals working in specialized palliative care units are prepared to deal with both somatic and psychiatric aspects. To avoid adding to the complexity of the care system, it may make sense to integrate the palliative care approach into all links of the care chain that already exists today.

Mental health is an essential dimension of quality of life that also plays a central role at the end of life. Unlike somatic diseases, the prognosis of a mental disorder is difficult to establish due to its heterogeneous and individual course, especially even in the preterminal stage, which is also overlaid by somatic complications. Therapeutic interventions for the mentally ill at the end of life thus remain predominantly oriented to the individual case, with the focus mostly on alleviating somatic complaints.

Palliative care pursues the goal of achieving the highest possible quality of life for those affected at the end of life. Palliative care involves the care and treatment of people with terminal, life-threatening and/or chronically progressive illnesses. It prevents suffering and complications and includes medical treatments, nursing interventions, and psychological, social and spiritual support at the end of life. The focus of palliative care is thus the period in which curation is no longer considered possible [1,2]. The WHO (2002) also recommends that palliative care should be used as early as possible and in addition to curative and rehabilitative measures during the course of a terminal illness (Fig. 1).

Accordingly, palliative care should be involved early and proactively and should also address chronically ill people with complex and unpredictable disease courses [3]. This understanding of palliative care, as defined in the national strategy of the Confederation and the cantons, thus in principle also includes mentally ill people.

However, the application of palliative care in psychiatry or, conversely, the application of psychiatric interventions in palliative care is not yet a matter of course today.

Palliative care in psychiatry – difficult framework conditions

Psychiatry often treats very seriously ill people, but hardly any dying people. This is because, unlike physical illnesses, mental illnesses (except by suicide or in advanced anorexia) rarely lead to death. In addition, since the Nazi period in Germany, when hundreds of thousands of mentally ill people fell victim to euthanasia programs, the term “palliative care” has been used reluctantly in psychiatry. Even the experts often disagree on whether the term may or should be applied [4]. Accordingly, the paradoxical situation arises that in psychiatry the principles of palliative care, such as interprofessionality of the treatment team, inclusion of close caregivers or multidimensionality of the approach, etc., are applied in principle in the treatment of chronically mentally ill people. Although the principles of palliative care, such as the interprofessionalism of the treatment team, the involvement of persons close to the patient, or the multidimensional approach, etc., are applied, palliative care is not usually referred to (as it is associated with death and end-of-life care in somatic diseases).

Mentally Ill in Palliative Care – Between the Stools

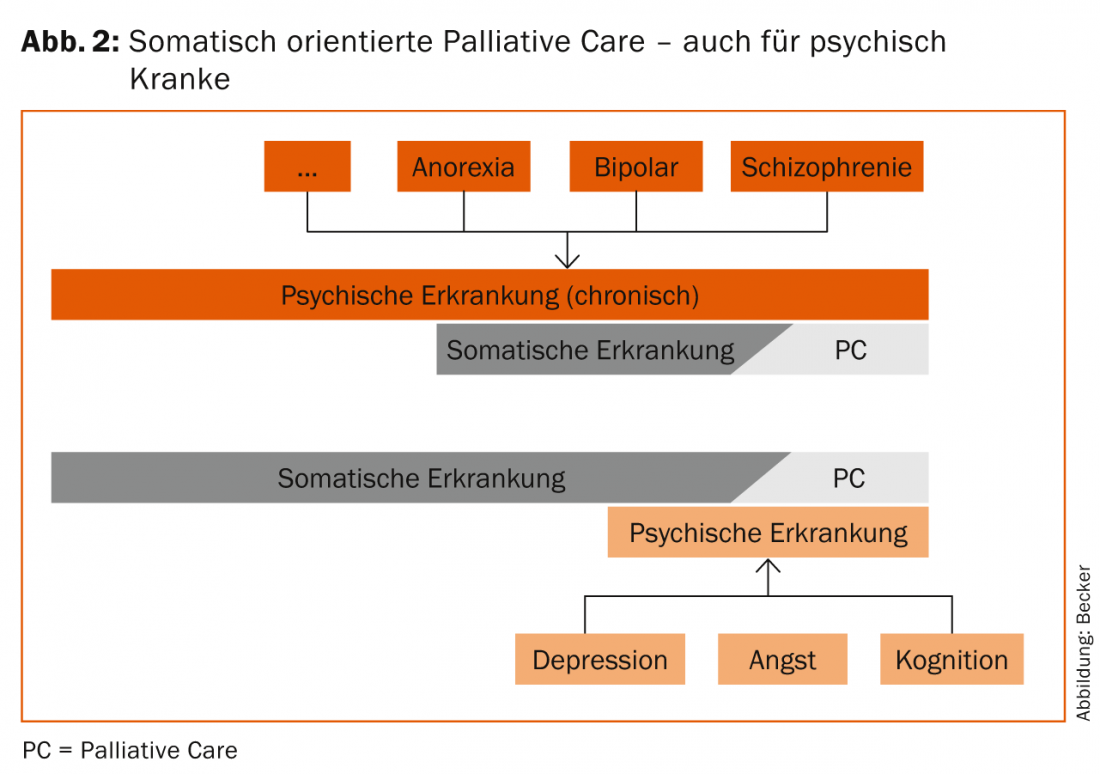

Patients with mental disorders are quite common in palliative care, with approximately 60% of all patients suffering from such disorders [5]. In a more somatically oriented palliative care, however, mental illnesses at the end of life are often perceived only as “side effects” and thus remain unrecognized or untreated. This has dramatic consequences for those affected themselves, as their suffering, e.g. depression in the context of an oncological disease, not only takes on an additional dimension, but is also associated with an increased risk of progression of the somatic primary disease (e.g. tumor) and subsequently with increased mortality. This applies both to patients with chronic mental illnesses (e.g., schizophrenia, bipolar personality disorder, or anorexia) who receive palliative care because of a somatic illness, and to those who develop mental symptoms only in the course of a (terminal) somatic illness. In the latter, depression, anxiety, sleep disturbances, restlessness, or acute states of confusion often occur in particular. Thus, neither psychiatric hospitals are geared toward the treatment and especially the medication (e.g., with morphine) of severe somatic illnesses, nor are general nursing facilities geared toward the care of the mentally ill. In Switzerland, there is currently a gap in the supply of institutions that are equipped to meet the special needs of severely mentally and somatically ill people. Depending on which disease is in the foreground, an undersupply of the others can be assumed. At the end of life, mentally ill patients in particular fall outside the scope of most care options with regard to appropriate “psychiatric palliative care” (Fig. 2).

Quality of care – a question of setting

The quality of care for the mentally ill at the end of life is highly dependent on the particular settings in which they receive care. For example, chronically mentally ill people are usually treated in psychiatric hospitals for only a limited time until their condition stabilizes. At the end of life, as soon as a somatic disease is in the foreground, there is usually a transfer either to an acute hospital or – if curative treatments are no longer possible – to long-term care institutions or to facilities for specialized palliative care. It should be noted, however, that even if these individuals are in a stable mental state, their situation is not comparable to that of individuals who do not have a biography characterized by a mental disorder. Specialized care concepts are required here, which include not only expertise in the care of the mentally ill, but also the knowledge that stressors can become effective at the end of life, which can lead both to an initial occurrence of mental disorders (e.g. depression) and to the recurrence or intensification of an already existing chronic mental illness (e.g. uncontrollable pain states, loss of autonomy).

Specialized palliative care units are very well prepared for these special end-of-life care situations and therefore offer optimal conditions for the care of those affected. The professionals working there are sensitized to both the somatic and psychiatric aspects of this living situation, so that psychological symptoms are usually well recognized and adequately treated. In general palliative care (nursing homes, Spitex, acute hospital), on the other hand, there is a much greater danger that psychological symptoms will be seen as a consequence of the physical illness and therefore trivialized [4]. However, psychopharmacological interventions or even psychotherapeutic processes can only be used if psychological symptoms are also recognized as such. In particular, the differential diagnosis of symptoms of a mental illness and drug-related side effects (e.g., pain treatment with opioids) is essential for the quality of life of those affected at the end of life.

Special challenges in the current supply situation

One of the specifics of chronic mental illness is that its course is often very difficult to predict. Disorders may appear at a young age, may also decrease in intensity in middle adulthood, or may reappear more pointedly in old age. In addition, depending on other health factors, patients respond differently to therapeutic interventions depending on the course of the disease. Thus, from the perspective of palliative care, there are hardly any truly palliative situations, but rather palliative phases that do not necessarily have to merge into a terminal phase as in palliative care oriented toward somatic diseases. Recognizing this and yet understanding and applying the principles of palliative care as important elements of treatment is a prerequisite for the best possible living situation for those affected and their close caregivers.

In the case of severe mental disorders as well as cognitive impairments (e.g. dementia), the clarification of the affected person’s capacity to judge in connection with their right to self-determination is of great importance. Particularly in the case of mentally ill patients, the ability to make judgments, as well as the overall mental state, is often very dependent on the course and type of the medication in question and can fluctuate greatly within a short period of time. This means that – unlike in the case of the various forms of dementia – the diagnosis or duration of a mental illness cannot be directly inferred from the person’s capacity to judge. The example of depression very clearly illustrates the associated challenge for care and treatment, also at the end of life: Even if severely depressed persons are in a difficult phase of their illness and are therefore unable to take an “objective” view of their life situation, they are not generally incapable of making judgments. In such a situation, a refusal to take antidepressant medication or to take life-prolonging measures must therefore be accepted in the first instance. Nevertheless, in such a case, respecting the right to self-determination should not be understood simply as accepting the refusal of treatment. Rather, the balance between autonomy or self-determination of the person concerned (despite existing restrictions) and the obligation to treat, i.e. the degree between gentle motivation and respect for the right to self-determination, must always be reassessed. This is a responsible and complex process that requires not only technical expertise but also a great deal of social competence and empathy from the entire environment. This is all the more so because living wills, which at least state the presumed will of the patient with regard to his or her final phase of life, are still rather rare in the psychiatric context.

Necessary improvements in the supply situation

Overall, the continuity of care for mentally ill people until the end of life has also improved in recent years. This is certainly also due to the National Palliative Care Strategy and the closer cooperation between acute and long-term care providers as well as outpatient services across the entire care chain. Nevertheless, there is a need for optimization in order to make palliative care more accessible to the mentally ill than it has been in the past. Sottas et al. [6] conclude that “palliative care services for the mentally ill are only part of the solution. Rather, it is a matter of working increasingly according to the guidelines of palliative care throughout psychiatric care.” First, it must be made clear that palliative care encompasses more than just end-of-life care and also addresses chronically ill people with complex and unpredictable courses of illness. In particular, it is important to recognize and take into account the specific characteristics of mental illness at the end of life. To achieve this, it is necessary to detach the concept of palliative care – as also envisaged in its original definition – from its sole reference to end-of-life care and to understand it in a broader sense, especially for chronically mentally ill people. If mental illnesses (chronic or acute) exist at the end of life, access to specialized palliative care must be provided on the one hand. On the other hand, opportunities for psychiatric consultation in long-term care need to be improved. Here, long-term institutions also need to be made even more aware of the options for geriatric psychiatric and therapeutic treatment. Conversely, especially in geriatric psychiatry, people are cared for until the end of their lives, for whose well-being palliative care appropriate to their needs is also necessary.

Overall, the care situation for mentally ill people at the end of life is complex. Whether the development of further specific palliative care structures may be an appropriate solution for different target groups is questionable. Further or additional structures increase the already costly and complex institutional cooperation and thus require even more coordination. To avoid adding to the complexity of the care system, integrating the palliative care approach into all links of the care chain that already exists today can make an important contribution.

Literature:

- Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH) and Swiss Conference of Cantonal Ministers of Health (GDK): National Strategy for Palliative Care 2013-2015. Bern 2012.

- Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH) and Swiss Conference of Cantonal Directors of Public Health (GDK): National Guidelines on Palliative Care. 2010.

- SAMS 2012: Palliative Care. Medical ethical guidelines and recommendations. www.samw.ch/de/Ethik/Richtlinien/Aktuell-gueltige-Richtlinien.html. Accessed February 2, 2015.

- Ecoplan: Palliative Care and Mental Illness. Report for the attention of the Federal Office of Public Health. Bern 2014.

- Mühlstein V, Riese F: Mental illness and palliative care. Switzerland Med Forum 2013; 13(33): 626-630.

- Sottas B, Brügger S, Jaquier A: Palliative care and mental illness from the user perspective. Sottas formative works 2014.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2015; 13(2): 16-19.