Globally, there is a trend toward increased use of preparations containing cannabis. Indications include pain problems or spasticity in the context of neurological diseases. Adverse effects are strongly dose-dependent.

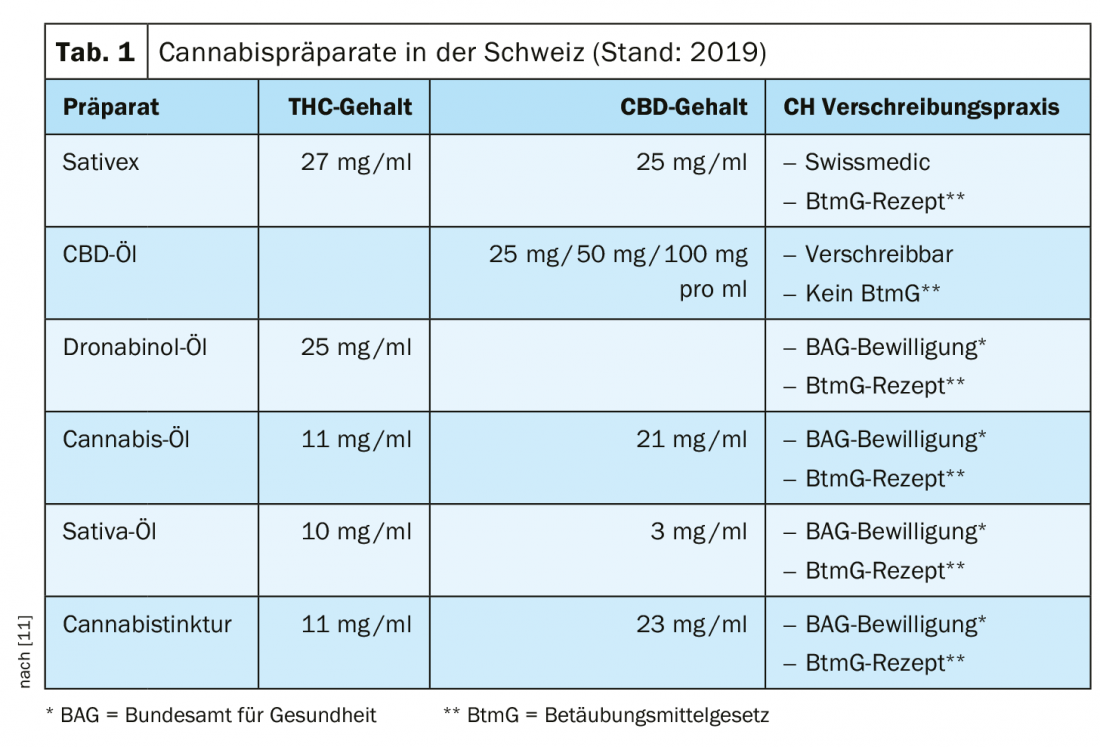

In Switzerland, the sublingual spray Sativex® [1] is currently the only medicinal product with cannabinoid active ingredients that is approved under the Therapeutic Products Act and can be prescribed by a physician without an exceptional authorization from the FOPH [1–2]. This preparation contains standardized extracts of THC (∆-9-tetrahydrocannabinol) and CBD (cannabidiol) in the ratio 1:1 [3]. In Switzerland, the indication is currently limited to use as a second-line therapy for spasticity in multiple sclerosis. For other THC- and CBD-containing medicinal products, a medical application must currently be submitted to the FOPH and there is an obligation to report side effects to Swissmedics [4]. This applies, for example, to Marinol® [5], a preparation containing the substance dronabinol (THC in synthetic form). Among other things, dronabinol is used as an analgesic and has antispasmodic and appetite-stimulating properties. Non-medicinal products containing CBD are freely available on the market in Switzerland if the THC content does not exceed 1%. Unlike THC, CBD has no psychoactive effect. In Germany, in addition to Sativex® [1] for the treatment of refractory spasticity in MS, Canemes® (Nabilon) [6], a synthetic THC variant for use in nausea and vomiting during chemotherapy, is also available.

Switzerland plans to change the law

Scientific research into cannabinoids is underway around the world. This should open up further areas of medical application. In many European countries, certain cannabinoids are approved for medicinal purposes. This also applies to Canada, where non-medical products have now also been legalized.

In Switzerland, the FOPH granted almost 3000 exemption permits for CBD- and THC-containing medicinal products in 2018 [4]. This involves a great deal of administrative work and leads to delays in treatment. In October 2019, the consultation process for a corresponding revision of the law was completed. PharmaSuisse supports efforts to facilitate access to cannabis-containing medicines [7]. The volage of the law provides for a legal separation of cannabis for medical and non-medical purposes. The abolition of the exemption requirement in Switzerland should make it easier for patients to obtain legally compliant medicines in the future. In terms of costs, the situation is such that the procedure for including a drug in the list of specialties (SL) is lengthy. According to the Federal Department of Home Affairs, by the end of 2020, a separate project will examine the financing of at least partial reimbursement for cannabis medicines without a marketing authorization via the compulsory health insurance, or a possible alternative financing [7].

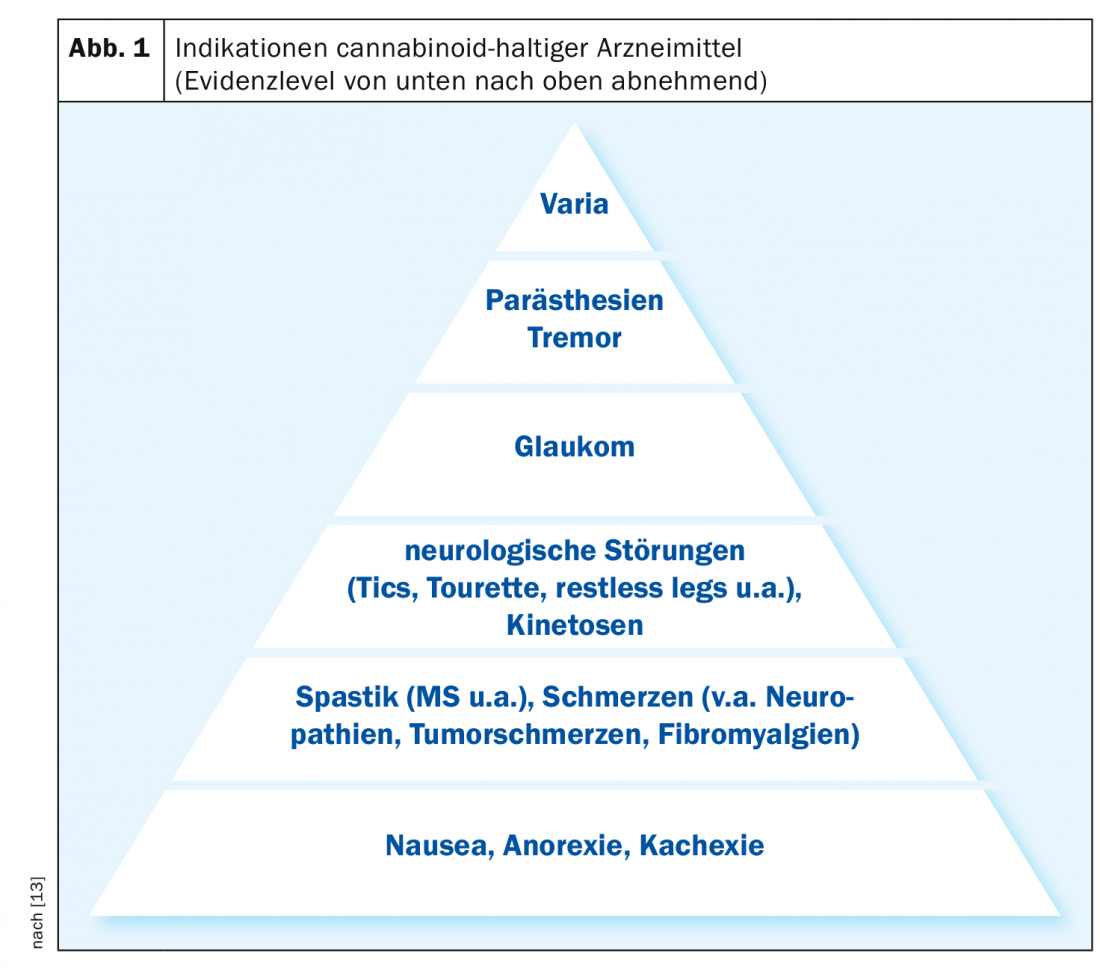

| Chronic pain and spasticity as main indication areas Legalization of cannabis-containing products for medical purposes is planned in Switzerland (BAG) [4]. This is due to the fact that the demand for treatments with cannabinoids has risen sharply in recent years. The main areas of application are chronic pain conditions (for example, neuropathic or tumor-related pain), spasticity and convulsions in the context of multiple sclerosis or other neurological diseases, and nausea and loss of appetite as side effects of chemotherapy. |

What is known so far about the mechanisms of action?

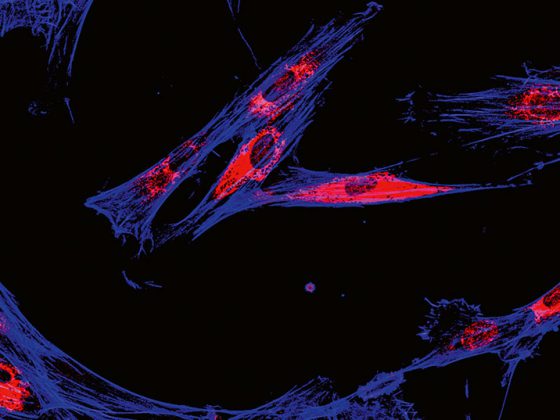

Cannabis flowers have a high content of the two cannabinoids THC and CBD. In addition, several hundreds of other substances are included, but little is known about their pharmacological effects [8]. THC and CBD develop their effect in the so-called endocannabinoid system. This is an endogenous regulatory system that plays an important role in the central nervous system and the immune system. In particular, the pharmacological effects of THC and CBD come from binding to CB1 and CB2 receptors [9]. More recent findings also show other active principles, e.g. anti-inflammatory properties of CBD, which are based on activation or inhibition of different cytokines (interleukin 10 and interleukin 17) [10]. Since the discovery of the cannabinoid receptors CB1 (1990) and CB2 (1993), there has been a surge of interest in cannbinoid-containing drugs. Besides CB1 and CB2 receptors, there are also PPAR-gamma (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor) and vanilloid receptors [11,12].

THC (∆-9-tetrahydrocannabinol): THC is a partial CB1/CB2 receptor agonist that has intoxicating, antispasmodic, antiemetic, analgesic, and appetite stimulating properties [11]. Synthetic or semi-synthetic THC extracts derived from hemp plants are mainly used for tumor pain treatment and symptom control in palliative medicine, chemotherapy-associated nausea and underweight in tumor and AIDS patients, painful spasticity in multiple sclerosis, and chronic neuropathic pain.

CBD (cannabidiol): CBD is a CB1/CB2 receptor agonist/antagonist/modulator [11]. Unlike THC, CBD has no intoxicating or addictive effects, but has mainly anti-inflammatory, anti-epileptic, anti-psychotic as well as analgesic effects. Areas of use include early childhood and refractory forms of epilepsy, certain mental health problems, and several other indications.

Drug-related side effects are dose-dependent

Psychotropic effects in adults occur on average from 10 to 20 mg THC (single oral dose) [12]. The therapeutically effective dose is lower in most patients [13]. The most common adverse drug reactions are: Fatigue, drowsiness, decrease in cognitive abilities, coordination disorders (orthostatic hypotension, dizziness), dry mouth, tachycardia, reddened eyes [9,14]. In therapeutic doses of cannabis preparations, physical or psychological dependence and development of tolerance are considered negligible by experts [13]. Any withdrawal symptoms – e.g. in the case of a higher dosage – should disappear completely within a few days [15]. Interaction with other substances mainly concerns benzodiazepines and alcohol (enhancement of sedative effects) as well as drugs acting on the cardiovascular system (e.g. beta-blockers, diuretics, tricyclic antidepressants) [13].

Literature:

- Sativex®: Swiss Drug Compendium, https://compendium.ch

- Therapeutic Products Act (HMG): www.admin.ch/opc/de/classified-compilation/20002716/index.html

- Oberhofer E: Prescribing cannabis – but correctly! Springer 2019, CME 16, 40. doi:10.1007/s11298-019-7351-z, https://link.springer.com/article/

- Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH): Amendment to the law on cannabis medicinal products, www.bag.admin.ch/bag/de/home/medizin-und-forschung/heilmittel/med-anwend-cannabis/gesetzesaenderung-cannabisarzneimittel.html

- Marinol®: PharmaWiki, www.pharmawiki.ch/wiki/index.php?wiki=marinol

- Nabilone: PharmaWiki, www.pharmawiki.ch/wiki/index.php?wiki=dronabinol

- pharmaSuisse: Swiss Pharmacists Association: www.pharmasuisse.org/data/docs/de/32789/191015-Auswertungsformular-Stellungnahme-phS-Cannabisarzneimittel.pdf?v=1.0

- Brenneisen R: Cannabis in the field of tension between experience and research. Prof. Dr. Rudolf Brenneisen, www.stcm.ch/files/mediaplanet_2019-03.pdf

- Grotenhermen F: Hemp as medicine. A practical guide. Nachtschatten Verlag AG (Solothurn) 2015: 40 – 52.

- Kozela E, et al: Cannabinoids decrease the th17 inflammatory autoimmune phenotype. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 2013; 8: 1265-1276.

- Fankhauser M: Cannabis as medicine. Manfred Fankhauser, Langnau SRO AG, Pain Clinic, Langenthal, Jan. 24, 2019

- Cannabis as Medicine Working Group. ACM Magazine 2015. Rüthen 2015: 9.

- Fankhauser M: Cannabis as medicine. Comparison of therapeutic use in Germany and Switzerland. Deutsche Apothekerzeitung 2015, www.deutsche-apotheker-zeitung.de/daz-az/2015/daz-30-2015/cannabis-als-arznei

- Kleiber D, Kovar KA: Effects of cannabis use, an expert opinion on pharmacological and psychosocial consequences. Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft (Stuttgart) 1998: 87.

- Grotenhermen F, Reckendrees B: The treatment with cannabis and THC. Solothurn 2014: 50.

FAMILY PRACTICE 2020; 15(4): 34-35

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2020; 18(4): 26-27.