Rapid microbiological clarification with sensitive and specific diagnostics is particularly important for gonococci because of the increase in antibiotic resistance. This review article provides knowledge on epidemiological and diagnostic aspects of infections with Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae.

In Switzerland and other European countries, there has been a rapid increase in sexually transmitted diseases in recent years. Rapid microbiological clarification with sensitive and specific diagnostics is particularly important for gonococci because of the increase in antibiotic resistance. This review article aims to provide knowledge on epidemiological and diagnostic aspects of infections with Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae.

Epidemiology

The numbers of infections with Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Treponema pallidum have increased significantly in absolute and relative terms in Switzerland and many European countries in recent years [1,2]. In Switzerland, these three bacterial pathogens and sexually transmitted viruses, such as HIV and the hepatitis B virus, must be reported by the diagnosing laboratory by law. Mandatory reporting of these diseases allows epidemiological surveillance (www.bag.admin.ch) and identification of risk factors and populations.

In the cantons of Basel-Stadt, Zurich, Geneva, and Vaud, the increase in sexually transmitted diseases is significant, whereas lower numbers have been documented in rural areas [1]. While it is likely that the great development in molecular diagnostics in recent years and the higher diagnostic coverage in urban centers explain part of this increase, careless sexual behavior is also very likely a contributing factor, although sound studies on this topic are scarce. It can be postulated that due to the possibility of HIV-specific pre-exposure prophylaxis, the fear of HIV infection has decreased significantly. This accepts a sexually higher risk for other infections. For certain at-risk populations with recurrent bacterial infections, prophylaxis against chlamydia and gonococci is therefore being discussed [3,4]. However, randomized studies in this area, including in the context of antibiotic resistance, have been lacking.

Neisseria gonorrhoeae: In 2015, 1895 confirmed infections of N. gonorrhoeae were reported in Switzerland, approximately 23% more than in the previous year with 1545 reports (Fig. 1A, www.bag.admin.ch). The majority of cases have affected men (about 80%). However, there has been a significant increase in both sexes since 2000. The incidence in Switzerland in 2015 was 9 per 100,000 population for women and 37 per 100,000 population for men [5]. Most cases occur in urban centers. The largest proportion of women was in the 15-24 age group, and among men, the 25-34 age group was particularly affected. A particularly sharp increase was seen in the group of men who have sexual contact with other men (MSM). It is estimated that only 3% of the sexually active population are MSM, but show an average of 38% of gonorrhea infections according to studies by the FOPH [5].

Chlamydia trachomatis: In 2015, 10,157 confirmed infections of C. trachomatis were reported in Switzerland, approximately 5% more than in the previous year with 9677 reports (Fig. 1B, www.bag.admin.ch). Overall, the number of cases has more than doubled in the last ten years. The incidence in Switzerland in 2015 was 161 per 100,000 population for women and 80 per 100,000 population for men [6]. This may be partly a pseudo-increase, as the percentage of positive tests to all tests performed has remained relatively stable [7]. Certainly, more asymptomatic infections are also being diagnosed, which has to do with the availability of sensitive molecular diagnostics and more frequent screening. Approximately 70% of infections are found in women, half of whom are between 15-24 years of age. In 70-90% of women, the infection is asymptomatic.

Diagnosis of N. gonorrhoeae – Specimen collection

Proper specimen collection is critical for cultural detection of N. gonorrhoeae. Gonococci tend to autolysis and are sensitive to desiccation and toxic substances from some lubricants [8].

Nowadays, liquid universal transport media are used as the collection and transport media of choice, which allow both bacterial culture and molecular diagnostic analyses (PCR) to be carried out (e.g. eSwab from Copan). Such transport media contain novel swabs with nylon flock fibers that increase sample collection yields compared to conventional swabs [9–11]. However, since there are diagnostic laboratories that require different transport vessels for gonococcal PCR and culture, we recommend consultation with the respective examining laboratory prior to sample collection.

The collection site should be chosen according to the sexual history [12]. In men, urethral swabs and first-jet urine are considered the investigational material of choice. Both samples should be collected at least one hour after the last micturition. A cervical smear should be taken as the investigational material of choice in women. Urine specimens in women should not usually be used because they are less sensitive compared with cervical smears [13]. In prepubertal girls, look for infections with gonococci vaginally rather than cervically [14]. In this age group, girls and boys should, of course, consult with a pediatrician.

Rectal swabs should be obtained with a rectoscope. The use of lubricants should be avoided, as these sometimes contain substances that are toxic to N. gonorrhoeae and reduce the sensitivity of the cultural detection. The collection technique should include as large a swab area as possible [15]. One study showed that in oropharyngeal infection, the widest possible area with additional pressure during swabbing, nearly doubled the detection rate [15]. For detailed guidance on optimal specimen collection for gonorrhea diagnosis, please refer to recommendations of the Swiss Federal Commission for Sexual Health and the Swiss Society for Infectious Diseases [13]. If gonococcal culture is desired, specimen collection should be performed prior to antibiotic administration. Transport of specimens to the laboratory should be as soon as possible and cultural culturing should preferably be done within twenty-four hours [16]. The sample can be shipped in the transport medium at room temperature.

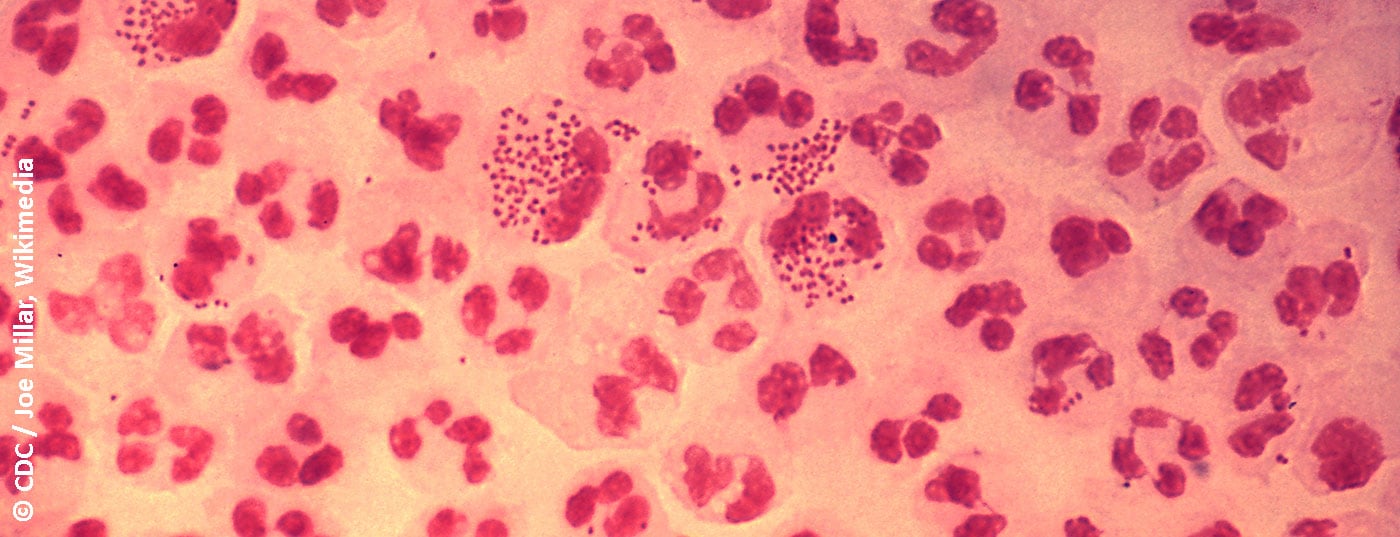

Microscopy

In symptomatic men, detection is possible with a Gram preparation from a urethral swab. Detection of Gram-negative, semiliterate to coffee-bean diplococci in polynuclear leukocytes is seminal for gonorrhea [17]. The sensitivity and specificity of this test is >90% [14]. In women, the sensitivity of microscopic analysis of a cervical smear is lower at 50-70%, but the specificity is >90% [14]. Of course, the reliability of microscopy depends on the quality of the sample and the experience of the examiner [14]. Microscopy is not useful for diagnosing oropharyngeal infection because apathogenic Neisseria spp. as a component of oral flora do not allow reliable differentiation from pathogenic N. gonorrhoeae.

Molecular biological methods

Today, several commercial systems are available that allow the detection of N. gonorrhoeae and C. trachomatis from the same sample by DNA amplification (PCR) – so-called duplex PCRs. The sensitivity and specificity of these systems are excellent with 95% each > [18–21] and they are for this reason nowadays standard for the detection of N. gonorrhoeae and C. trachomatis infections [22].

Recently, multiplex PCRs have also become available, allowing broader workup with additional pathogens such as Mycoplasma hominis, M. genitalium, Ureaplasma urealyticum, and U. parvum [23,24]. Molecular testing with (semi)-automated systems is less costly than culture methods and allows high throughput of clinical samples especially for rapid screening. The time from sample receipt in the laboratory to the result (the so-called turn-around time) is usually only a few hours, and the results are often available on the same day, depending on the time of sample receipt. PCR methods should not be used to document short-term treatment success because N. gonorrhoeae DNA can be determined several weeks after successful treatment using sensitive detection methods [14]. Reinfections or resistant isolates may also be responsible [25]. In this case, the medical history should be taken again and followed by cultural detection with antibiotic resistance testing.

Other detection methods

Point-of-care (POC) tests for leukocyte esterase detection and immunochromatographic assays show low sensitivity in N. gonorrohoeae infections, with only 23-85% and 60-94%, respectively [26]. At the moment, PCR-based methods are therefore clearly superior.

Bacterial culture

Cultural detection of viable gonococci is necessary to detect potential treatment failure and to collect reliable data on resistance status and trends. Gonococci are usually grown on selective media. The media contain antibiotics and antifungals to inhibit the accompanying bacterial and fungal flora. A typical medium, which is also used in our laboratory, is the Martin-Lewis agar based on cooking blood agar. The innoculated plates are checked daily for growth and incubated for 48 hours at 36°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Gonococci grow as small, smooth, gray colonies on the first day or two. Thus, cultural detection of live bacteria usually takes between two to three days, as opposed to PCR, but offers more diagnostic options.

Accurate identification of suspect colonies on the culture plate has previously been accomplished by testing various biochemical reactions, which have taken several hours to establish a biochemical profile. Nowadays, the identification of a bacterial isolate is performed within a few minutes using Matrix Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization – Time of Flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry. MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry has since become the identification standard for a wide variety of bacteria and fungi in microbiology laboratories [27]. However, the time-limiting factor remains the cultivation of the bacteria on an agar plate.

Resistance position

The World Health Organization (WHO) recently compiled a list of resistant germs for which new effective antibiotics should be urgently developed – cephalosporin-resistant and fluoroquinolone-resistant N. gonorrhoeae are among them (www.who.int). Resistance testing after cultural detection of N. gonorrhoeae is important [13,28]. Despite the urgency, surveillance of antimicrobial resistance is not standardized or sufficiently established in many countries [29]. The following antibiotics are usually tested for N. gonorrhoeae: Cefixime, ceftriaxone, fluoroquinolones (e.g., ciprofloxacin), and azithromycin. Resistance testing requires an additional two days after identification.

Treatment of N. gonorrhoeae is complicated by antibiotic resistance development. While penicillin was still considered the therapy of choice in the 1970s, the rise of plasmid-mediated penicillinases (penicillin-cleaving enzymes) and chromosomal penicillin resistance has disrupted penicillin therapy [30]. Similarly, the development of plasmidic and chromosomal resistance to tetracycline led to the use of broad-spectrum cephalosporins in the 1980s and later to the use of fluoroquinolones [30]. The 1990s showed an increase in fluoroquinolone-resistant isolates, initially in Southeast Asia, followed by rapid spread to many countries. The global increase in cefixime-resistant isolates is progressing and is of concern because this antibiotic is currently recommended as a single oral dose for treatment [30]. Another problem is the increase in resistance to ceftriaxone. Due to the increase in multi-drug resistant N. gonorrhoeae, certain guidelines now already recommend a combination of intramuscular ceftriaxone and oral azithromycin as the first choice in treatment [30].

For current details on the therapy of gonorrhea, please refer to current “Recommendations of the Federal Commission for Sexual Health and the Swiss Society for Infectiology” [13].

Diagnosis of C. trachomatis – Specimen Collection

Chlamydiae are obligate intracellular bacteria, so it is important to have as many cells as possible in the sample. This is achieved by rubbing the swab during sample collection [31].

The usual sites for specimen collection in symptomatic genital infections with C. trachomatis are the endocervix in women and the urethra in men. Less invasive samples such as a vaginal swab in women and a midstream urine or urethral meatus swab in men are also possible today, thus increasing test acceptance by patients. The sensitivity and specificity of PCR detection of C. trachomatis in noninvasively collected specimens are comparable to specimens obtained directly from the cervix or urethra [32]. Urine samples from women are usually less suitable for PCR detection of C. trachomatis because they show suboptimal sensitivity [29]. Self-collected vaginal swabs are described in CDC laboratory recommendations as accurate and acceptable specimens [33]. For chlamydia detection by PCR, the material should be processed after 48 hours at the latest [31]. The sample can be transported at room temperature. For detailed guidance on optimal specimen collection, please refer to “Recommendations of the Federal Commission for Sexual Health and the Swiss Society for Infectiology” [28].

Infection with C. trachomatis serotypes L1, L2, and L3 is associated with increased pathogenicity and leads to the clinical picture known as lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV). LGV infections occur primarily in at-risk populations such as MSM. In this case, detection takes place in rectal or urethral swabs, pus or puncture material from affected lymph nodes.

Molecular biological methods

As the method of choice, chlamydia is nowadays detected by DNA amplification methods (PCR). Detection can be performed simultaneously for C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae with excellent sensitivity and specificity (see above). The importance of reliable diagnostics and epidemiological surveillance will be illustrated with the following example: C. trachomatis have 4-8 copies of a 7500 nucleotide long plasmid. This plasmid is therefore a very attractive target for a PCR detection method, as increased diagnostic sensitivity is achieved by multiple copies. Between November 2005 and August 2006, there was an unexpected drop in the incidence of C. trachomatis in a particular region of Sweden [34]. The 25% reduction in diagnosed cases was initially interpreted as the success of preventive measures. However, this was actually a result of a genetic alteration with a 377 base pair deletion in this said plasmid [34]. As a result, commonly used commercial PCR tests failed to detect chlamydiae in the sample material. This so-called “Swedish” or “Scandinavian” variant of C. trachomatis is prevalent in Sweden and can meanwhile also be found in other Scandinavian countries [35]. So far, only isolated cases have been reported in other countries. The manufacturers of PCR diagnostics have reacted quickly and adapted and improved the detection methods accordingly. Chlamydia associated with LGV can be determined by PCR for detection of the specific LGV serotypes [36,37]. In a more severe course of the disease, e.g. with enlarged lymph nodes, LGV should be sought – especially in MSM – and treated accordingly [38]. As with N. gonorhoeae, DNA from non-viable bacteria may remain detectable for a prolonged period of time in C. trachomatis infection – PCR should therefore not be repeated within three weeks [39].

Other detection methods

The serological antibody detection or a Chlamydia antigen ELISA with an immunofluorescence reaction are hardly used in routine anymore.

Resistance position

Since chlamydia can only be cultivated in complex cell cultures and this is only done in specialized laboratories, resistance testing is not usually performed. The therapy of choice is antibiotics with intracellular activity such as doxycycline and azithromycin. The development of resistance has not yet been shown in C. trachomatis [28]. For treatment guidelines of C. trachomatis infection, we refer to the “Recommendations of the Federal Commission for Sexual Health and the Swiss Society for Infectiology” [28].

Summary

Sexually transmitted diseases such as N. gonorrhoeae and C. trachomatis are currently experiencing a renaissance – partly explained by the availability and sensitivity of modern molecular diagnostics – but not exclusively. Especially in times of increasing antibiotic resistance in N. gonorrhoeae and particularly virulent chlamydiae (lymphogranuloma venereum), a rapid and reliable diagnosis should be made. In addition to molecular diagnostic detection, culture-based antibiotic resistance testing is also recommended for N. gonorrhoeae.

Take-Home Messages

- Sexually transmitted diseases such as N. gonorrhoeae and C. trachomatis are currently experiencing a renaissance. This increase cannot be explained exclusively by the availability and sensitivity of modern molecular diagnostics.

- Increasing antibiotic resistance in N. gonorrhoeae and detection of particularly virulent chlamydiae (lymphogranuloma venereum) require rapid and reliable diagnostics.

- In addition to molecular diagnostic detection, culture-based antibiotic resistance testing is also recommended for N. gonorrhoeae.

Literature:

- Federal Office of Public Health DÖG. HIV, syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydiosis in Switzerland in 2015: an epidemiologic review. FOPH Bulletin 2016; 46: 12-13.

- (ECDC) ECfDPaC. Sexually transmitted infections in Europe 2013. ECDC surveillance report 2015: 1-124.

- Dubourg G, Raoult D: The challenges of preexposure prophylaxis for bacterial sexually transmitted infections. Clinical microbiology and infection: the official publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases 2016; 22 (9): 753-756.

- Unemo M, Bradshaw CS, et al: Sexually transmitted infections: challenges ahead. Lancet Infect Dis 2017; 17 (8): e235-e279.

- Federal Office of Public Health DÖG: Gonorrhea in Switzerland in 2015. FOPH Bulletin 2016; 46: 27-30.

- Federal Office of Public Health DÖG: Chlamydiosis in Switzerland in 2015. FOPH Bulletin 2016; 46: 32-33.

- Schmutz C, Burki D, et al.: Testing for Chlamydia trachomatis: time trends in positivity rates in the canton of Basel-Stadt, Switzerland. Epidemiol Infect 2013; 141 (9): 1953-1964.

- Vogel U, Forsch M: Gran negative aerobic and facultative anaerobic cocci. In: Neumeister M, Geiss HK et al. (Ed.) Microbiological diagnostics. Stuttgart, New York: Thieme; 2009.

- Coorevits L, Vanscheeuwijck C, et al: Evaluation of Copan FLOQSwab for the molecular detection of Chlamydia trachomatis by Abbott RealTime CT PCR. Acta clinica

- Belgica 2015; 70 (6): 398-402.

- Jun JK, Lim MC, et al. Comparison of DRY and WET vaginal swabs with cervical specimens in Roche Cobas 4800 HPV and Abbott RealTime High Risk HPV tests. J Clin Virol 2016; 79: 80-84.

- Tan TY, Ng LS, et al: Evaluation of bacterial recovery and viability from three different swab transport systems. Pathology 2014; 46 (3): 230-233.

- den Heijer CDJ, Hoebe C, et al: A comprehensive overview of urogenital, anorectal and oropharyngeal Neisseria gonorrhoeae testing and diagnoses among different STI care providers: a cross-sectional study. BMC Infect Dis 2017; 17 (1): 290.

- Toutous Trellu L, Oertle D, et al: Gonorrhea: new recommendations on diagnosis and treatment. Swiss Medical Forum 2014; 14 (20): 407-409.

- Ng LK, Martin IE: The laboratory diagnosis of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. The Canadian journal of infectious diseases & medical microbiology = Journal canadien des maladies infectieuses et de la microbiologie medicale / AMMI Canada 2005; 16 (1): 15-25.

- Mitchell M, Rane V, et al: Sampling technique is important for optimal isolation of pharyngeal gonorrhea. Sex Transm Infect 2013; 89 (7): 557-560.

- Wind CM, de Vries HJ, et al: Successful Combination of Nucleic Acid Amplification Test Diagnostics and Targeted Deferred Neisseria gonorrhoeae Culture. Journal of clinical microbiology 2015; 53 (6): 1884-1890.

- Spence JM, Wright L, Clark VL: Laboratory maintenance of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Current protocols in microbiology 2008; Chapter 4: Unit 4A 1.

- Perry MD, Jones RN, Corden SA: Is confirmatory testing of Roche cobas 4800 CT/NG test Neisseria gonorrhoeae positive samples required? Comparison of the Roche cobas 4800 CT/NG test with an opa/pap duplex assay for the detection of N gonorrhoeae. Sex Transm Infect 2014; 90 (4): 303-308.

- Ursi D, Crucitti T, Smet H, Ieven M: Evaluation of the Bio-Rad Dx CT/NG/MG(R) assay for simultaneous detection of Chlamydia trachomatis, Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Mycoplasma genitalium in urine. European journal of clinical microbiology & infectious diseases: official publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology 2016; 35 (7): 1159-1163.

- Wong KC, Ho BS, et al: Duplex PCR system for simultaneous detection of Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis in clinical specimens. Journal of clinical pathology 1995; 48 (2): 101-104.

- Meyer T, Klos C et al: Performance evaluation of the

- PelvoCheck CT/NG test kit for the detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae. BMJ open 2016; 6 (1): e009894.

- Low N, Unemo M, et al: Molecular diagnostics for gonorrhea: implications for antimicrobial resistance and the threat of untreatable gonorrhea. PLoS medicine 2014; 11 (2): e1001598.

- Del Prete R, Ronga L et al: Simultaneous detection and identification of STI pathogens by multiplex real-time PCR in genital tract specimens in a selected area of Apulia, a region of Southern Italy. Infection 2017; 45 (4): 469-477.

- Fernandez G, Martro E, et al: Usefulness of a novel multiplex real-time PCR assay for the diagnosis of sexually-transmitted infections. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin 2016; 34(8): 471-476.

- Bissessor M, Whiley DM et al: Persistence of Neisseria gonorrhoeae DNA following treatment for pharyngeal and rectal gonorrhea is influenced by antibiotic susceptibility and reinfection. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 60 (4): 557-563.

- Watchirs Smith LA, Hillman R et al: Point-of-care tests for the diagnosis of Neisseria gonorrhoeae infection: a systematic review of operational and performance characteristics. Sex Transm Infect 2013; 89 (4): 320-326.

- Dierig A, Frei R, Egli A: The fast route to microbe identification: matrix assisted laser desorption/ionization-time of flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS). Pediatr Infect Dis J 2015; 34 (1): 97-99.

- Tarr P: Sexually transmitted infections with Chlamydia trachomatis: Recommendations of the Swiss Federal Commission for Sexual Health (FSCG) and the Swiss Society of Infectiology (SSI). FOPH Bulletin 2017; 35: 8-14.

- Unemo M, Shipitsyna E, Domeika M: Eastern European S, Reproductive Health Network Antimicrobial Resistance G. Gonorrhoea surveillance, laboratory diagnosis and antimicrobial susceptibility testing of Neisseria gonorrhoeae in 11 countries of the eastern part of the WHO European region. APMIS: acta pathologica, microbiologica, et immunologica Scandinavica 2011; 119 (9): 643-649.

- Elias J, Frosch M, Vogel U: Neisseria. In: Jorgensen JH, ed. Manual of clinical microbiology. 11th ed. Washington, DC: ASM Press; 2015: 635-651.

- Jacobs E: Mycoplasmas and obligate intracellular bacteria. In: Neumeister B, Geiss HK, BRaun RW, Kimmig P, eds. Microbiological diagnostics. Stuttgart, New York: Thieme; 2009.

- Gaydos CA, Essig A, Vogel U: Chlamydaceae. In: Jorgensen JH, ed. Manual of Clinical Mircobiology. 11th ed. Washington: ASM Press; 2015: 1106-1121.

- Hobbs MM, van der Pol B et al. From the NIH: proceedings of a workshop on the importance of self-obtained vaginal specimens for detection of sexually transmitted infections. Sexually transmitted diseases 2008; 35 (1): 8-13.

- Ripa T, Nilsson P: A variant of Chlamydia trachomatis with deletion in cryptic plasmid: implications for use of PCR diagnostic tests. Euro surveillance: bulletin Europeen sur les maladies transmissibles = European communicable disease bulletin 2006; 11 (11): E061109 2.

- Unemo M, Clarke IN: The Swedish new variant of Chlamydia trachomatis. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2011; 24(1): 62-9.

- de Roche M, Sawatzki M et al: Lymphogranuloma venereum. An old disease in a new dress. Der Internist 2011; 52 (5): 584-589.

- Goldenberger D, Dutly F, Gebhardt M: Analysis of 721 Chlamydia trachomatis-positive urogenital specimens from men and women using lymphogranuloma venereum L2-specific real-time PCR assay. Euro surveillance: bulletin Europeen sur les maladies transmissibles = European communicable disease bulletin 2006; 11 (10): E061018 4.

- Stoner BP, Cohen SE: Lymphogranuloma venereum 2015: clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 61 (8): S865-873.

- Gaydos CA, Crotchfelt KA, et al: Molecular amplification assays to detect chlamydial infections in urine specimens from high school female students and to monitor the persistence of chlamydial DNA after therapy. J Infect Dis 1998; 177 (2): 417-424.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2017; 27(6): 22-28