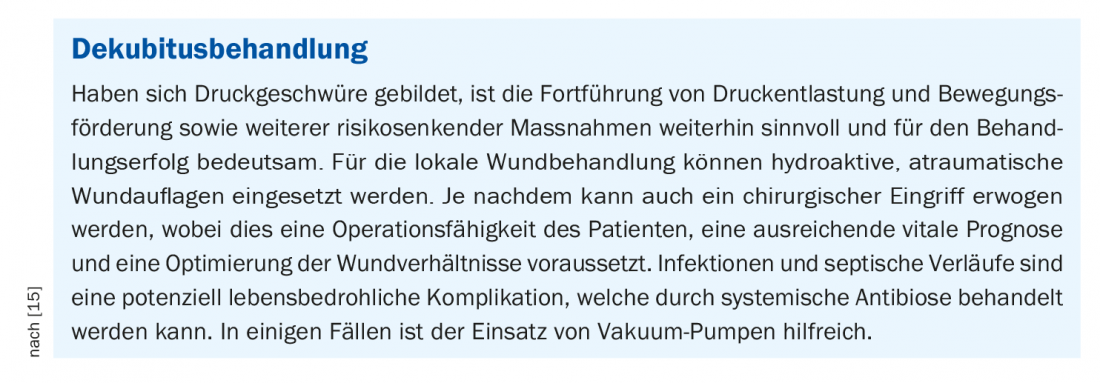

Pressure ulcers are severe complications of multimorbidity and immobility. Pressure ulcer risk can be estimated using the Braden scale. Measures to relieve pressure and promote movement can reduce the incidence of pressure ulcers in bedridden patients. These interventions, in combination with local wound treatment, are also helpful for pressure ulcer therapy.

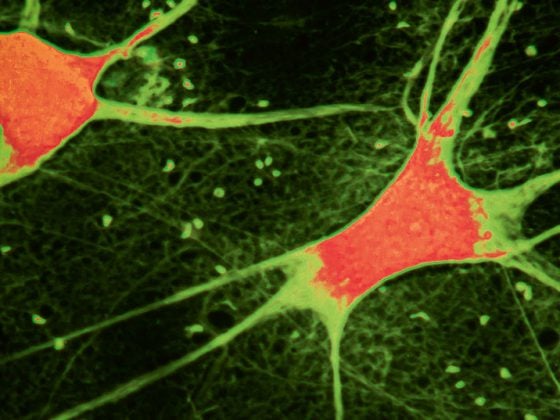

Pressure ulcer is defined as localized damage to the skin and/or underlying tissue, typically over bony prominences, as a result of pressure and shear forces [1,2]. In the ICD-10, pressure ulcers are coded as diseases of the skin and skin appendages [3]. Pathophysiologically, it is a wound that develops under persistent pressure in the upper layers of the skin and spreads outward like an ulcer and into deeper tissue layers if targeted countermeasures are not initiated [4,5]. Concomitant inflammatory reactions are common, for example, as local bacterial colonization or systemic infections. If the skin damage is extensive, fluid and protein may be lost via exudates.

Pressure ulcer risk assessment

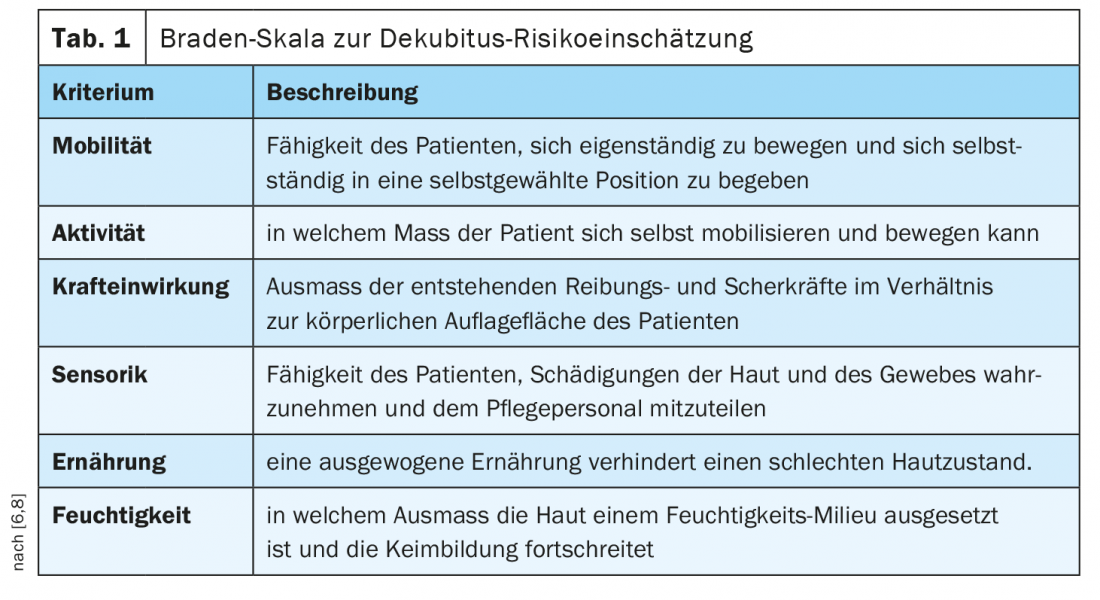

The Braden scale is a multilevel scheme for the classification of pressure ulcer risk in bedridden and dependent patients (Table 1) [6]. It is composed of six criteria that are considered risk factors for the development of a pressure ulcer. For each criterion there are four levels with a point system. The total score results in a score indicating the extent of risk (>18 points=low, 15-18=general, 13-14 points=medium, 10-12 points=high, <9 points=very high). At the first sign of a pressure sore, the test should be repeated after about 24 to 48 hours to obtain a clear result. If there are no signs of a wound ulcer, a new repetition is based on the score achieved. A maximum of 23 points can be achieved. The lower the score at the end of the test, the higher the risk for skin- and tissue-damaging pressure ulcers.

Limited activity and mobility are among the most important risk factors. If someone is completely bedridden and unable to get up and walk, this is called limited activity. Patients who are incapable of independent small changes in position while lying or sitting are said to have mobility restrictions. Vascular and circulatory diseases with a risk of deficient blood circulation are among the other factors that can lead to bedsores. Very moist skin conditions (e.g., due to wetting or sweating) are also a risk factor, as the moisture is a good breeding ground for bacterial infections as well as inadequate nutrition and hydration (e.g., protein, vitamin deficiencies) [7].

Measures in case of pressure sore risk

If a patient is at risk of pressure ulcers, there is a wide range of measures to prevent the development of a pressure ulcer [7]: Pressure relief and pressure modification, positioning, alternating positioning, micropositioning, pressure relief in sedentary persons at risk, assistive devices.

The best prophylaxis is to relieve or distribute pressure through regular physical exercise and/or by exposing vulnerable areas of the body. The frequency varies individually. While some patients experience skin redness within two hours, others can lie on one spot for up to four hours without risk of pressure ulcers.

It is recommended that the patient be positioned in an oblique30° lateral positionon the right and left, alternating with the supine position. In this angle, hardly any bones are supported, but mainly the soft tissues on the back. If the upper body is inclined at an angle of more than 30° or in a 90° lateral position, the pressure on parts of the body particularly at risk of decubitus increases. If redness that cannot be pushed away is visible on parts of the body with bony prominences, this is a sign that they have not yet recovered from the previous pressure and should be further spared.

Mattresses can have an impact on pressure distribution. Since there is no pressure distribution in a standard mattress, it must be changed/relocated more frequently than a viscoelastic mattress. Patients at high risk of pressure ulcers for whom manual repositioning is not possible should lie on an energetic alternating pressure mattress.

Even the smallest changes in position, which is also referred to as microsupport, can already cause a reduction in pressure or a different distribution of pressure. This can be done with the help of folded towels or flat pillows, which are alternately placed under the exposed parts of the body.

In a sitting position (chair), the pressure of the body weight is greatest over the ischial tuberosities; without pressure distribution, a pressure ulcer develops very quickly there. For people at risk, it is therefore helpful to relieve pressure with a seat cushion by ensuring that pressure is distributed over the entire seat surface. In addition, the patient should lean on the armrests and place the feet on the floor or a footrest (if the feet hang freely in the air, the body slides backwards in the chair). The pelvis should be slightly bent forward and the thighs slightly bent.

In addition to the above measures, there are various aids to relieve pressure: it has been shown that fewer new pressure ulcers occur when viscoelastic foam mattresses are used than with standard mattresses. As the body sinks into the viscoelastic mattress, the support surface is increased and thus the support pressure is reduced. Thus, the overlying tissue is less compressed and better supplied with blood. To prevent a pressure sore on the heels, it is important that the heels are exposed. A pillow placed under the calf can completely relieve the pressure on the heel, while keeping the knee slightly bent. The choice of appropriate aids should be tailored to individual needs and disease-related limitations. Important criteria are the type of underlying disease, the level of pressure ulcer risk, any pre-existing pressure ulcers, and the degree of mobility of the affected person [9]. There are pressure-relieving aids for the abdomen/torso (e.g. static positioning aids), buttocks (e.g. seat cushions), back or whole body (e.g. supports for soft positioning, dynamic reclining aids for repositioning).

Literature:

- NPUAP/EPUAP 2014: Prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers, abridged guideline: www.epuap.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/german_quick-reference-guide.pdf

- Kottner J: Decubitus classification, Priv.-Doz. Dr. Jan Kottner, Charité Berlin, 02.03.2018, www.dnqp.de/fileadmin/HSOS/Homepages/DNQP/Dateien/Veranstaltungen/20WS_Kottner_AG6.pdf

- WHO: International Classification of Diseases, ICD-10, www.icd-code.de/icd/code/L00-L99.html

- Black J, et al: National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel’s updated pressure ulcer staging system. Dermatol Nurs 2007; 19: 343-349.

- Jennifer A, et al: Decubital ulcers – pathophysiology and primary prevention. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2010; 107(21): 371-382; DOI: 10.3238/arztebl.2010.0371.

- Pressure ulcer prophylaxis – Braden risk assessment; www.dekubitus.de/dekubitusprophylaxe-braden-skala.htm

- Langer A: Pressure ulcer. Prophylaxis of pressure ulcer. How to counsel family caregivers? DAZ 2015, no. 15, p. 58, 09.04.2015.

- Standard Systeme GmbH Hamburg, www.standardsysteme.de/wissenswertes/braden-skala/

- BVMed: Avoiding pressure sores, recognizing them early and treating them with appropriate aids, German Medical Technology Association, www.bvmed.de

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2020; 15(10): 20-22