Analogous to the S3 guideline of the DKG 2014, recommendations can be made depending on the stage. Stage I: Here, total mesorectal excision (TME) alone is standard. Stage II and III: Preoperative radio(chemo)therapy is standard in the treatment of locally advanced rectal cancer. This therapy halves the local recurrence rate, regardless of the surgical procedure. If long-term therapy is planned as radiochemotherapy, the chemotherapy should be 5-FU based. Long-term radiochemotherapy leads to downsizing and downstaging, allowing for better operability.

In the multimodality treatment of rectal cancer, radiochemotherapy/short-term radiotherapy represents an integral component in stage II and III. In recent decades, a switch from adjuvant to neoadjuvant treatment regimens has occurred due to minimization of side effects and local recurrence rates.

Classification

The international definition is as follows: Tumors localized 16 cm or less from the anocutaneous line as measured by rigid endoscope are considered rectal carcinomas. It is divided into lower third: 0-6 cm, middle third: 6-12 cm and upper third 12-16 cm.

Risk factors

Obesity, lack of exercise and smoking are considered risk factors for developing rectal cancer. Likewise, there is evidence that low-fiber and high-fat diets increase the incidence of rectal cancer. Specific dietary measures cannot be recommended to date [1,2].

Any histologically confirmed adenoma increases the risk of colorectal cancer, especially multiple (≥3) adenomas or large (>1 cm) adenomas.

First-degree relatives with colorectal cancer are also a risk factor. In this case, relatives should have colorectal cancer screening ten years before the index patient.

Ulcerative colitis leads to an increased likelihood of developing colorectal cancer compared to the normal population. Corresponding recommendations for diagnosis and therapy are available in an S3 guideline [3].

Colorectal cancer screening

Colorectal cancer screening is generally recommended from the age of 50. Complete colonoscopy has the highest sensitivity and specificity for finding carcinomas and adenomas and should therefore be used as a standard procedure [3]. There are no clear upper age limits [4]. Concomitant diseases should also be considered [5].

Diagnostics

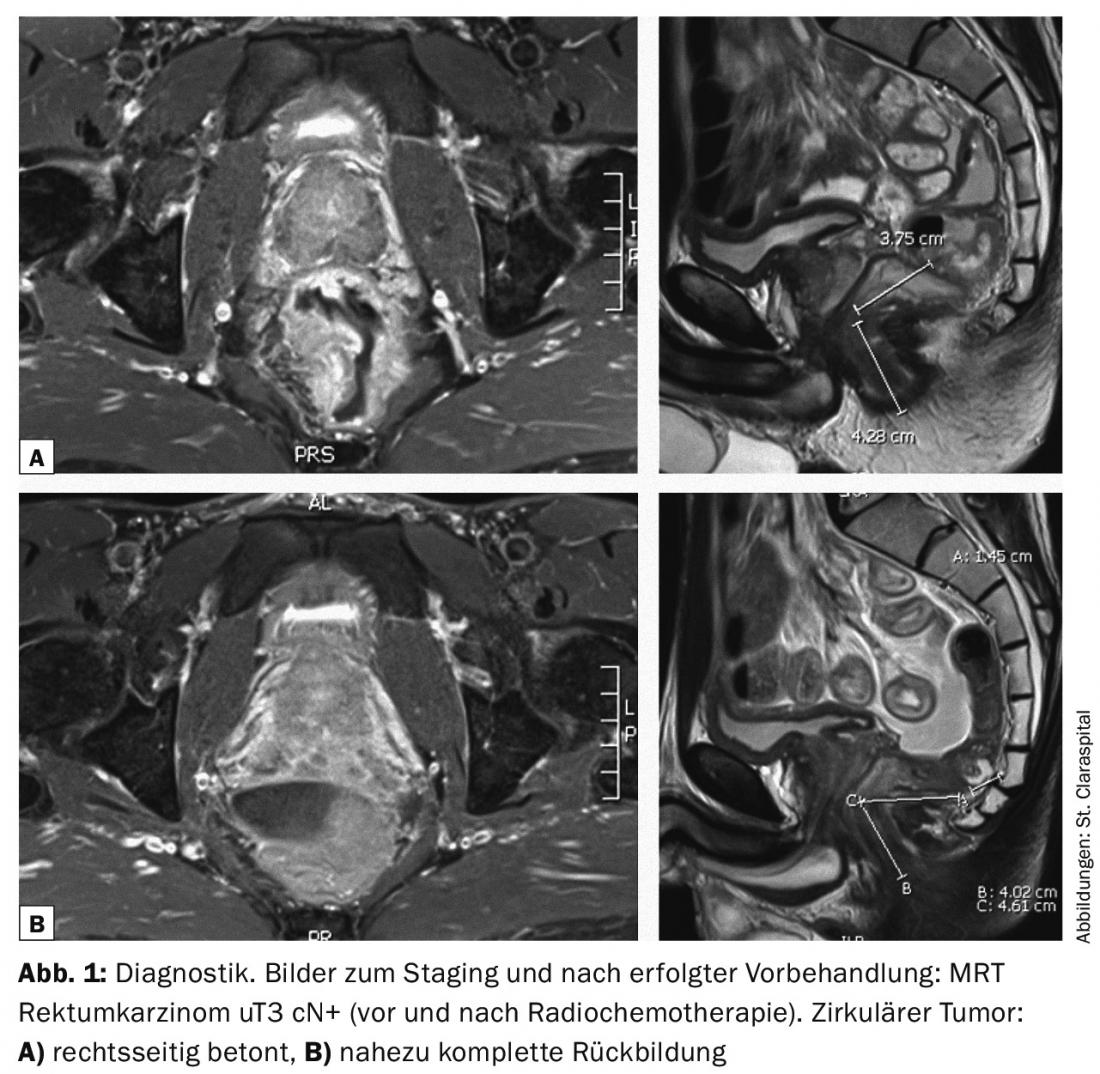

MRI and endosonography are considered the diagnostic imaging modalities of choice for assessing preoperative nodal status and extent of the primary tumor. A principal problem is the potential “overstaging” in preoperative diagnostics, especially when assessing nodal status. A possible metastasis is clarified by means of cross-sectional imaging. Histologic confirmation is obtained by biopsy during rectoscopy.

Therapy concepts

Multimodality therapy of rectal cancer is interdisciplinary. One influence is the tumor location. Treatment of lower and middle third rectal cancer is largely standardized [3], whereas treatment of upper third rectal cancer is either the same as that of middle and lower third rectal cancer or also analogous to colon cancer [3]. The latter is supported by the results in the TME trial, which had shown no significant benefit from radiotherapy in the upper third (10-15 cm from anocutaneous) compared with surgery alone [6]. In contrast, the German CAO/ARO/AIO-94 trial showed no differences in local recurrence rates in the respective thirds, so by analogy, the treatment of all rectal cancers would be the same [7].

Neoadjuvant radio/radiochemotherapy

Radiation therapy should be indicated from preoperative stage uT3 or from any N+ stage (UICC stage II and III). In principle, neoadjuvant radiochemotherapy, possibly short-term radiation alone, is recommended for every patient in this situation [3]. A Cochrane analysis published in 2011, which included 9410 patients and 12 randomized trials, showed a 50% reduction in the relative risk of local recurrence with neoadjuvant short-term radiation and also with neoadjuvant radiochemotherapy compared with total mesorectal excision (TME) alone for stage II and III UICC

[8].

Short-term vs. long-term irradiation

The short-term regimen 5× 5 Gy does not result in tumor shrinkage. Late toxicity tends to be increased compared with surgery alone or long-term treatment. Surgery is performed after short-term radiotherapy one week after completion of radiotherapy. This treatment option thus shortens the pretreatment interval. Thus, in the case of planned intensive chemotherapy, e.g., in the presence of extensive lymph node metastases or distant metastases, this concept does not lead to a delay in systemic therapy [3]. Short-term radiotherapy may also be considered when downstaging is not desired or necessary, e.g., in well-operable T3 N0 tumors [3,9,10].

A Polish study had shown significantly better response with long-term treatment in comparison of preoperative long-term irradiation vs. short-term irradiation, both in terms of downstaging and downsizing and in terms of sphincter preservation and R0 resection [11].

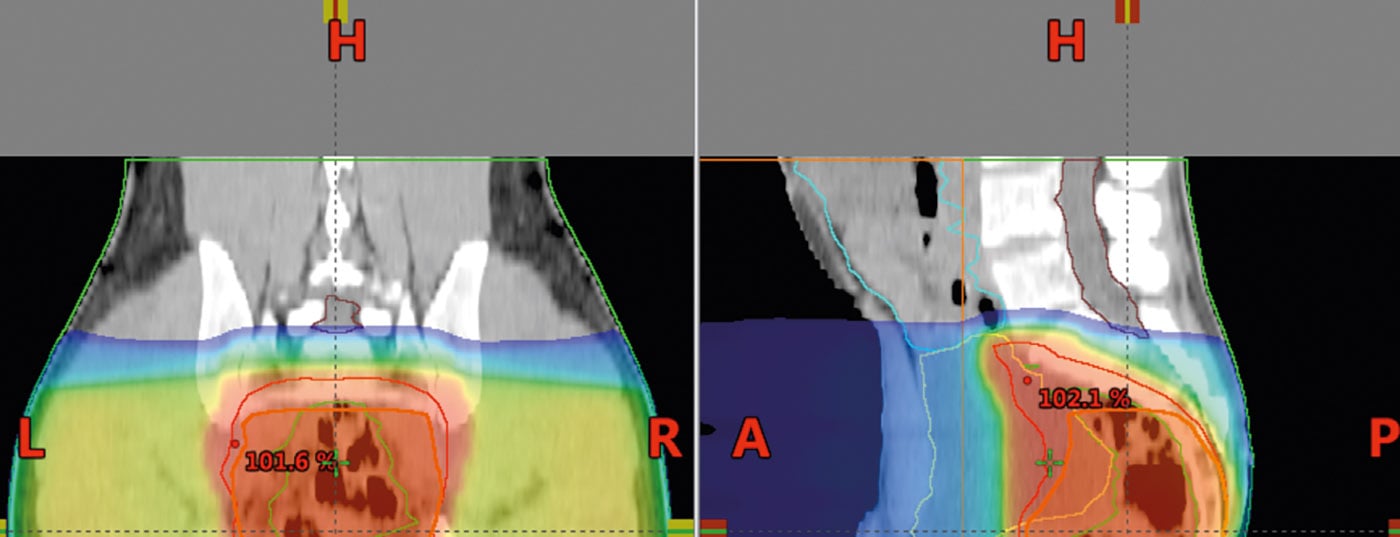

Preoperative long-term radiochemotherapy over five to five and a half weeks thus aims at tumor reduction (Figs. 1 and 2 ) and thus improved operability; in the case of deep-seated rectal tumors, it also has the goal of sphincter preservation [3]. The operation is then performed here at intervals of six to eight weeks. Longer intervals after preoperative treatment also appear reasonable.

Neoadjuvant radiochemotherapy should include 5-FU

be based [3]. Two large trials investigated the additional benefit of chemotherapy to neoadjuvant radiation, both with 5-FU. Recent studies combined capecitabine with oxaliplatin and/or irinotecan and demonstrated no additional benefit with increased toxicity [12–14].

Adjuvant radio/radiochemotherapy

Postoperative radiochemotherapy, which has been recommended for many years, has higher toxicity and lower efficacy compared with preoperative methods [15]. It is usually considered only when primary surgery demonstrates a higher tumor stage, then with an indication for radiation chemotherapy [3].

Postoperative radiation alone reduces the local recurrence rate but has no effect on overall survival [16].

Postoperative chemotherapy alone, in the case of contraindications to radiation (e.g., previous radiation of the prostate or in the case of st.n. radiation of gynecologic tumors), also reduces the risk of recurrence but is inferior to postoperative combined radiochemotherapy [17].

Target volume and dosage

The irradiation position in the prone position often offers advantages over the irradiation position in the supine position due to better protection of the small intestine in the “ventroposition”/displacement of the small intestine into the recess of the perforated board (Fig. 3). Care should also be taken to ensure that the bladder is well filled, as this can also allow the small bowel to be moved cranially.

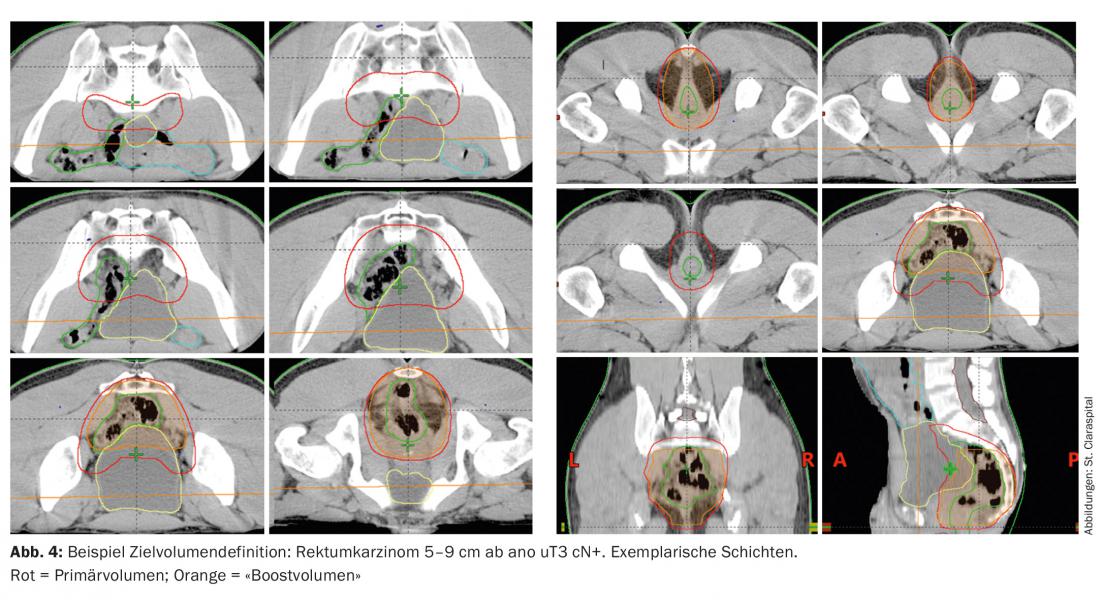

The target volume includes the entire tumor including the mesorectum with the presacral and iliac lymph nodes (target volume definition Fig. 4). In tumors of the upper and middle rectum, the sphincter should be omitted to avoid posttherapeutic insufficiencies and incontinence [3]. In the case of deep-seated tumors and infiltration of the skin, irradiation of the inguinal lymph nodes should be considered, since in this case lymph node infiltration may occur inguinally.

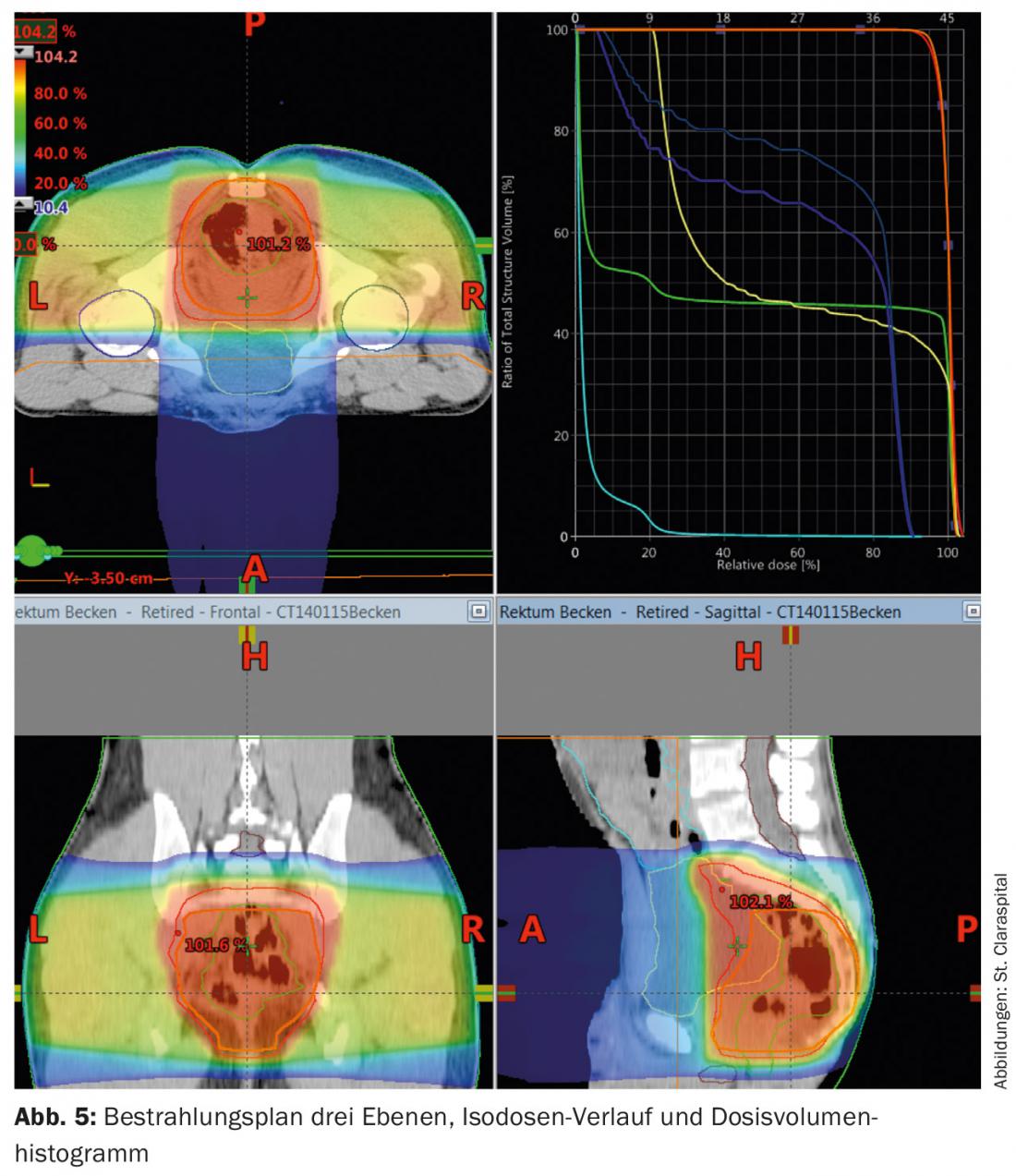

Computed tomography is used for radiation planning. These are used to calculate the dose and define the area to be irradiated (“target volume definition”). The dose for long-term irradiation is 45-50.4 Gy with single doses of 1.8 Gy, postoperatively also 45-50.4 Gy (Fig. 5) . A “boost concept” and omission of risk structures after 45 Gy offer the possibility to reduce toxicity.

Intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) may be able to reduce toxicity to the small intestine or other high-risk structures and organs compared with the 3-field technique and should be used in this situation [18,19].

Operation

For mid and distal rectal cancer, TME (transanal endoscopic microresections) is the recommended radical surgery [3]. This reduces the recurrence rate compared to other non-radical surgical procedures [20,21]. Partial TME with sufficient distal safety distance of 5 cm is an option for upper third carcinomas due to lower morbidity (ESMO consensus 2011) [3]. Recently, TEM has also been evaluated in small tumors of stage T1-2 N0 [22,23].

Adjuvant chemotherapy

Postoperatively, the recommendation for chemotherapy should follow preoperative staging [3]. This recommendation is supported by the German CAO/ARO/AIO-94 trial and the EORTC 22921 trial, which showed a survival benefit of 6% absolute and 4% for progression-free survival [15]. A Dutch phase III trial is currently evaluating adjuvant chemotherapy with capecitabine vs. observation after 5× 5 Gy of short-term radiation and surgery. More intensive chemotherapy regimens, such as combination with oxaliplatin, are still being evaluated.

Side effects

These occur locally during irradiation: Diarrhea, constipation, proctitic discomfort at doses from 20-30 Gy, dysuria, bleeding, mucosal discharge, as well as epitheliolysis in deep-seated tumors and, rarely, incontinence and impotence over a longer period of time, in addition to adhesions and fibrosis of other organs, as well as impairment of hormone balance (especially estrogen in women). The risk rate for grade III toxicities (CTC) is 3-11% with the use of modern radiotherapy techniques. In combination with chemotherapy, systemic side effects such as blood count changes and an increase in the rate of infection, allergic reactions, nausea and vomiting may also occur. Many of the symptoms can be alleviated with medications for nausea/vomiting, diarrhea, and skin care.

Literature:

- Ning Y, Wang L, Giovannucci EL: A quantitative analysis of body mass index and colorectal cancer: findings from 56 observational studies. Obes Rev 2010; 11(1): 19-30.

- Austin GL, et al: Moderate alcohol consumption protects against colorectal adenomas in smokers. Dig Dis Sci 2008; 53(1): 116-122.

- DKG S3 guideline: www.krebsgesellschaft.de/leitlinien-onkologie.de, version August 2014.

- Pox CP, et al: Efficacy of a Nationwide Screening Colonoscopy Program for Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterology 2012.

- Whitlock EP, et al: Screening for colorectal cancer: a targeted, updated systematic review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med 2008; 149(9): 638-658.

- Peeters KC, et al: The TME trial after a median follow-up of 6 years: increased local control but no survival benefit in irradiated patients with resectable rectal carcinoma. Ann Surg 2007; 246(5): 693-701.

- Sauer R, et al: Preoperative versus postoperative chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced rectal cancer: results of the German CAO/ARO/AIO-94 randomized phase III trial after a median follow-up of 11 years. J Clin Oncol 2012; 30: 1926-1933.

- Fleming FJ, Påhlman L, Monson JR: Neoadjuvant therapy in rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 2011 Jul; 54(7): 901-912.

- Junginger T, et al: [Rectal carcinoma: is too much neoadjuvant therapy performed? Proposals for a more selective MRI based indication]. Zentralbl Chir 2006; 131(4): 275-284.

- Smith N, Brown G: Preoperative staging of rectal cancer. Acta Oncol 2008; 47(1): 20-31.

- Bujko K, et al: Sphincter preservation following preoperative radiotherapy for rectal cancer: report of a randomised trial comparing short-term radiotherapy vs. conventionally fractionated radiochemotherapy.Radiother Oncol 2004; 72(1): 15-24.

- Bosset JF, et al: Chemotherapy with preoperative radiotherapy in rectal cancer. N Engl J Med 2006; 355(11): 1114-1123.

- Gerard JP, et al: Preoperative radiotherapy with or without concurrent fluorouracil and leucovorin in T3-4 rectal cancers: results of FFCD 9203. J Clin Oncol 2006; 24(28): 4620-4625.

- Rödel C, Sauer R: Integration of novel agents into combined-modality treatment for rectal cancer patients. Radiation Oncol 2007; 183(5): 227-235.

- Sauer R, et al: Preoperative versus postoperative chemoradiotherapy for rectal cancer. N Engl J Med 2004; 351(17): 1731-1740.

- Rödel C, Sauer R: Radiotherapy and concurrent radiochemotherapy for rectal cancer. Surg Oncol 2004; 13(2-3): 93-101.

- NIH consensus conference. Adjuvant therapy for patients with colon and rectal cancer. Jama 1990; 264(11): 1444-1450.

- Parekh A, et al: Acute gastrointestinal toxicity and tumor response with preoperative intensity modulated radiation therapy for rectal cancer. Gastrointest Cancer Res 2013 Sep; 6(5-6): 137-143.

- Engels B, et al: Preoperative intensity-modulated and image-guided radiotherapy with a simultaneous integrated boost in locally advanced rectal cancer: report on late toxicity and outcome. Radiother Oncol 2014 Jan; 110(1): 155-159.

- Brown CJ, Fenech DS, McLeod RS: Reconstructive techniques after rectal resection for rectal cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008; (2): CD006040.

- Fazio VW, et al: A randomized multicenter trial to compare long-term functional outcome, quality of life, and complications of surgical procedures for low rectal cancers. Ann Surg 2007; 246(3): 481-488; discussion 488-490.

- Moore JS, et al: Transanal endoscopic microsurgery is more effective than traditional transanal excision for resection of rectal masses. Dis Colon Rectum 2008; 51(7): 1026-1030; discussion 1030-1031.

- Kuhry E, et al: Long-term results of laparoscopic colorectal cancer resection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008; (2): CD003432.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2015; 3(8): 16-19.