Dementia patients are mostly elderly and multimorbid. Close care that takes comorbidities into account is important – but challenging because of the unique characteristics of these patients.

Dementia is associated with many comorbidities, including hypertension, depression, pain disorders, diabetes, coronary heart disease, and stroke. Only 5% of all dementia patients have no other disease [1]. The presence of cardiovascular and neuropsychiatric comorbidities complicates the management of dementia patients.

Close supervision necessary

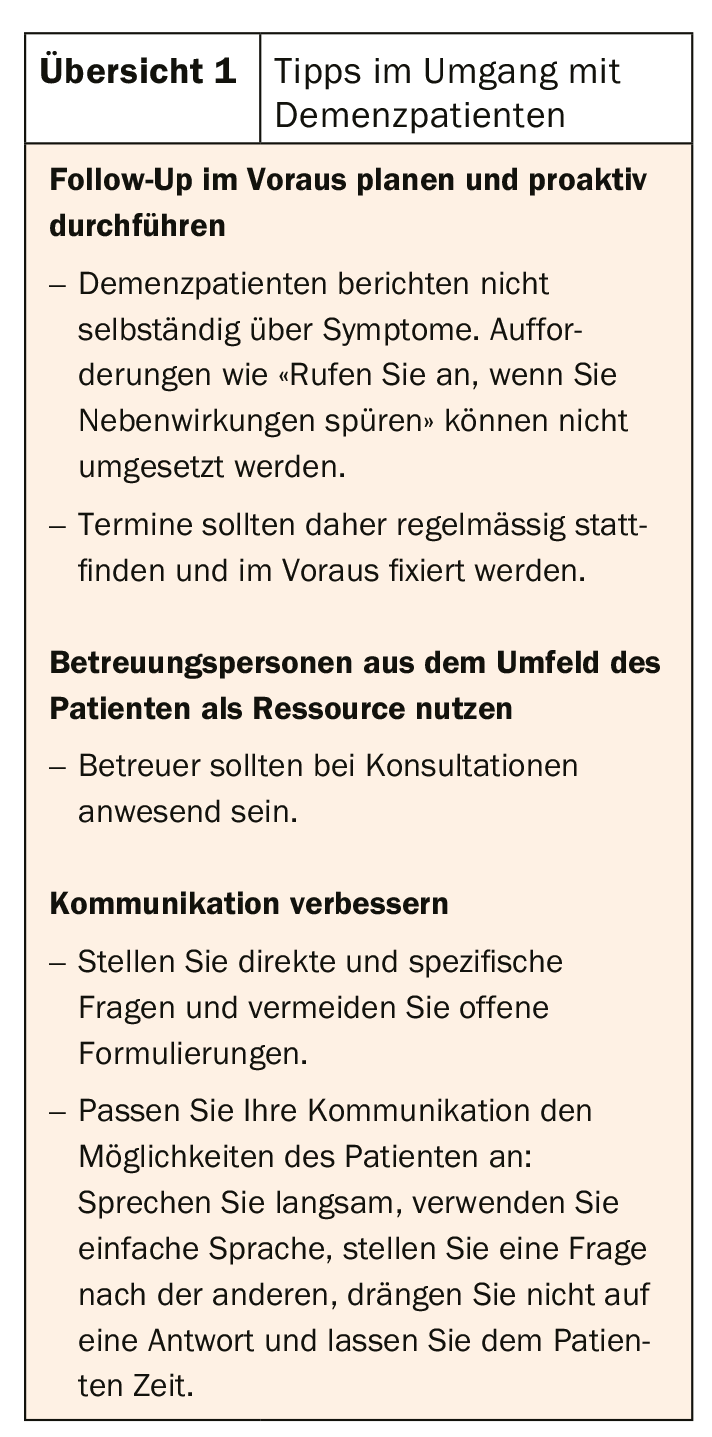

Kristian Seehen Frederiksen, MD, working at the Danish Dementia Research Centre at the Rigshospitalet, University of Copenhagen (DNK), draws attention to further difficulties: “Two of the greatest challenges in the care of dementia patients are the loss of the ability to self-reflect and dwindling autonomy.” The decrease in the ability to express oneself verbally makes communication visibly more difficult. The perception of pain also changes, discomfort is communicated differently, and the behavior displayed often cannot be readily decoded by interaction partners. As cognition becomes more impaired, patients find it difficult to communicate symptoms or medication use at all. These characteristics make the management of dementia patients a difficult undertaking. Regular, proactive follow-up and an adapted communication approach are important (overview 1).

The fact that patients with dementia must be closely monitored is also shown by statistical data from Great Britain. There, dementia is the leading cause of death among women, according to figures from the Office for National Statistics. Another reason for close care is that dementia is associated with a range of neurological and psychiatric symptoms. Behavioral symptoms include aggression and agitation, depression and anxiety, psychotic symptoms, apathy, or hyperactivity. At the motor level, hemiparesis, dysarthria, incontinence, parkinsonism, unsteady gait and falls, and chorea and dystonia may occur. Patients with dementia also often suffer from sleep disorders. Epileptic seizures are also not uncommon, with a prevalence of 10-22%.

In order to provide optimal care to dementia patients, it is essential to consider specific features of certain forms of dementia (e.g., regarding LBD: hypersensitivity to antipsychotics, management of REM sleep disturbance, hallucinations, and parkinsonism).

With regard to drug therapy, various aspects are relevant. For example, cardiovascular risk factors, multimedication, motor symptoms, fitness to drive, sleep quality, possible presence of epilepsy, nutrition, pain symptoms, and end-of-life and palliation decisions must be considered.

Blood pressure control – yes or no?

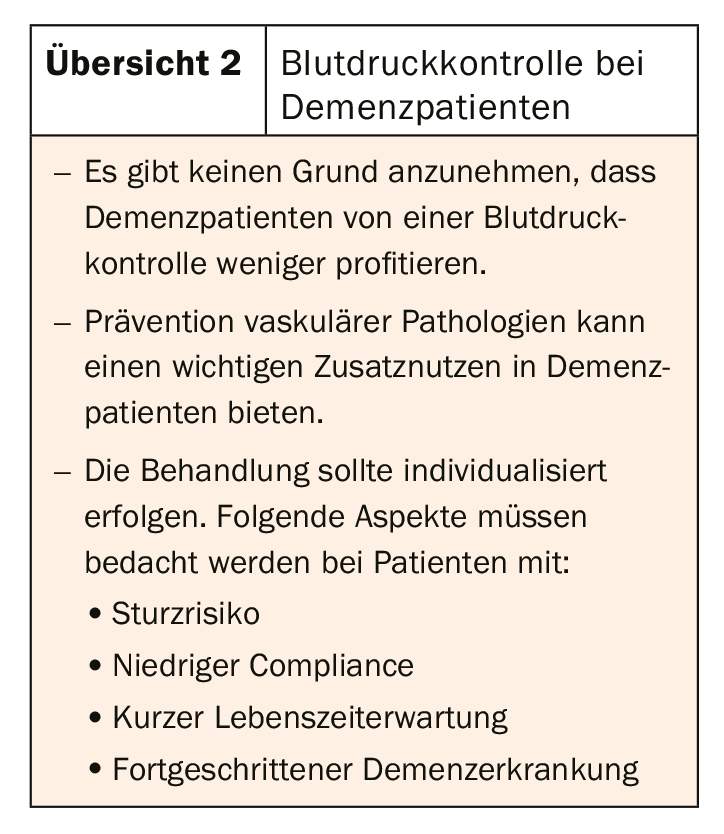

Cardiovascular risk factor assessment includes addressing hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, atrial fibrillation, type 2 diabetes, and obesity. Blood pressure control in particular plays an important role in the development of dementia, as suggested by a recently published metastudy [2]. Pooled results from the SPRINT-MIND trial and other studies showed a significant effect of primary prevention of hypertension. However, as far as the treatment of hypertension in patients who already have dementia is concerned, no conclusive studies currently exist. “We don’t currently have enough evidence to say whether treating hypertension in dementia patients slows disease progression,” Frederiksen, MD, qualifies. However, hypertension is known to have a deleterious effect on cognition in older age (e.g., bez. vascular remodeling, small-vessel disease, alteration of endothelial function, disruption of neurovascular coupling, verm. promotion of beta-amyloid plaques) [3].

The “other side of the coin,” on the other hand, about which we know quite well, is the possible side effects of antihypertensives. While four observational studies were able to rule out an association between antihypertensives and fall risk, two referred to an association between antihypertensives and orthostatic hypotension in dementia patients.

This leaves two key questions: should hypertension in dementia patients be treated intensively or less intensively? And can the treatment goals proposed in the guidelines, which are based on cognitively healthy individuals, be extrapolated to patients with dementia? An answer is still pending. The EAN Guideline, due in early 2020, also finds insufficient study evidence. However, good practice aspects provide orientation (overview 2).

Problem polypharmacy

Compared to congitively healthy people, dementia patients take significantly more different medications. The prevalence of polypharmacy (taking ≥5 different medications) in people with dementia was determined in 2014 by a Danish cross-sectional study (n=1,032,120; age ≥65) [4]. Polypharmacy was present in 62.6% of dementia patients vs. 35.1% of cognitively healthy individuals. The same distribution was found with respect to the occurrence of inappropriate medication (45% vs. 29.7%). Another study looked at how often physicians see their dementia patients at all to prescribe medications, or how often a patient can obtain their medications from the pharmacy without a prior visit. This was measured by the number of prescriptions repeatedly issued without a visit. This was found to occur more often in dementia patients than cognitively healthy patients (5-9 wdh: 43.2% dementia patients vs. 32.4% cognitively healthy) [5].

Psychotropic medications are often prescribed. Although the number of antidepressants has declined over the past several years, second-generation antipsychotics are becoming more common. Here, too, polypharmacy is not uncommon. 75.8% of dementia patients treated with antipsychotics use at least two different psychotropic substances during the treatment period. Antipsychotics and antidepressants were most commonly combined [6].

In view of these figures, it is natural to ask what obstacles stand in the way of optimal medication. The reasons for the numbers could be an incomplete medical history, lack of time, established beliefs about a particular drug, limited freedom of choice, difficulties in patient communication, or problems defining treatment goals. However, various guidelines at least provide an overview of which drug combinations may be harmful [7–9]. MD Frederiksen also refers to the practitioner’s fear of negative consequences. Following the motto “If it ain’t broke, don’t try to fix it,” treatment providers would rather continue as before instead of adjusting the regime. “But I think ultimately it all comes down to forging a strong alliance with the patient. In a pre-planned follow-up, the physician and patient should then also discuss what to do if symptoms arise,” says Frederiksen, MD.

Getting to the bottom of behavioral psychological symptoms

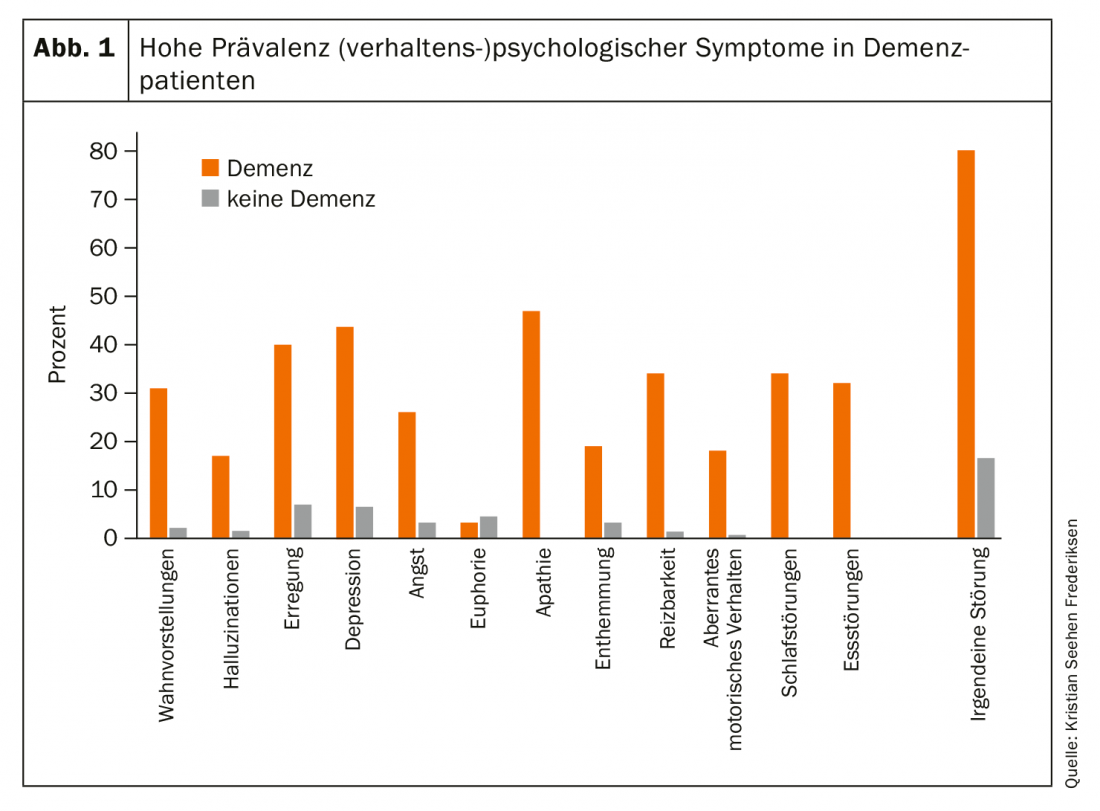

Psychological symptoms are highly prevalent in dementia patients (Fig. 1). They can occur in all stages and forms of dementia and are expressed by the patient in different ways (e.g. pain, sadness, aggression). With regard to treatment, Frederiksen, MD, suggests that it is primarily the sedating side effects of antipsychotics that would be used to counter these symptoms. But it is far more important to identify the underlying etiologic factors, he said:

- What is the problematic behavior and who actually practices it? Is the patient behaving pathologically – or is the caregiver simply losing patience with him?

- When does the behavior occur? What are trigger factors?

Furthermore, it is important to document and measure behavior in order to establish a treatment goal. Very central here is to come to a common understanding about therapeutic options.

In addition to a careful physical and laboratory examination, it is important to consider the altered environment and altered routines as causes of behavioral psychological phenomena. One way to alleviate the symptoms is to make certain adjustments in this regard. MD Frederiksen also advocates that caregivers be trained to handle difficult situations. For example, if a patient calls for help in his or her room due to loneliness or anxiety, but immediately falls silent as soon as the caregiver enters the room, this behavior can be changed by having the caregiver spend time with the patient even when he or she is well. Treatment with antipsychotics may be indicated in certain cases (e.g., severe aggression or problematic psychotic symptoms).

Pain management: start low, go slow!

Although chronic pain disorders are common in dementia patients and severely limit QoL, they are often not adequately recognized and treated. Neurodegenerative processes affect pain pathways differently depending on type, extent, and lesion location. Diagnosis is difficult, and therapy is complex due to physiologic changes in the patient and a variety of comorbidities and drug interactions.

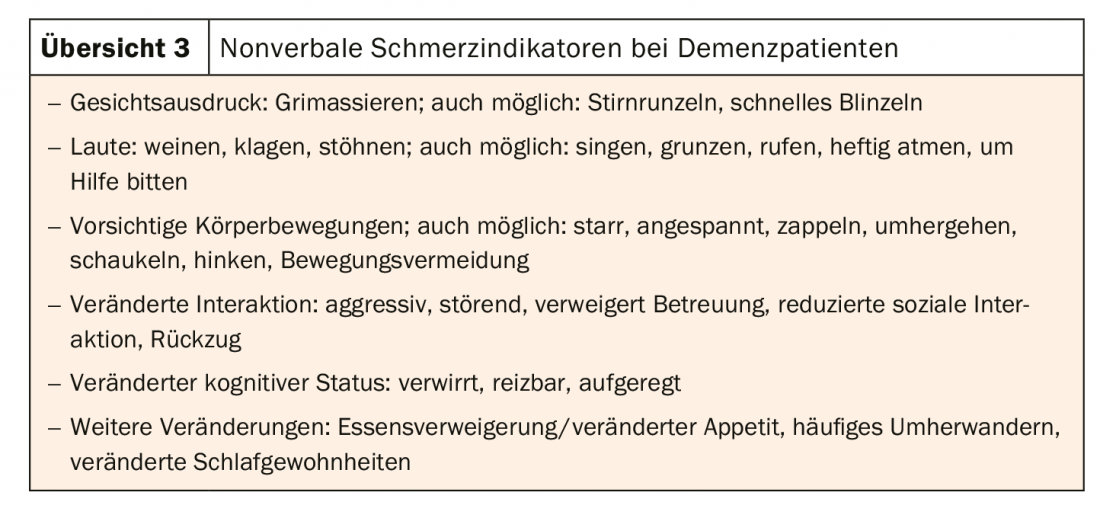

Milica Gregorič Kramberger, MD, director of the Center for Cognitive Disorders at UMC Ljubljana (SVN), advocates a multimodal approach to both diagnosis and treatment. Due to the wide range of causes in chronic pain, it is important to proceed in a structured way, using validated and standardized tools where possible. This includes consideration of current and past illnesses, surgeries and medications, a comprehensive physical examination, and relevant laboratory tests. This can rule out infections, constipation, wounds, undetected fractures, and urinary tract infections as causes. Of course, “simple” reasons such as hunger, thirst and emotional needs should also be considered. When talking to the patient, pain should be inquired about in various ways, because the patient, due to his illness, is not able to deal with all formulations in the same way. One way of quantifying pain are one-dimensional pain scales (simple-descriptive, numeric i.e. intensity 0-10, visual-analog), which can be filled out reliably by more than 80% of all dementia patients (think of aids like glasses or hearing aids!). Nonverbal indicators of pain are of increased importance given the changes in expressive ability and manner (overview 3).

The treatment of chronic pain is multimodal. Non-pharmacological forms of intervention include physical therapy and psychological support, and collaboration with the caregiver is very important. If medication is essential, comorbidities and comedication must be carefully considered; regular reevaluation is imperative to monitor efficacy and potential side effects in these mostly elderly, multimorbid patients with cognitive impairment. Evidence regarding the safety of analgesics in dementia patients is currently scarce; clinical trials addressing this issue are urgently needed [10]. Dr. Kramberger recommends starting with nonopioid medications first and switching to opioids if necessary. Neuroleptics and benzodiazepines for pain control should be avoided, and anticonvulsants should be used cautiously. SNRIs can be used as adjunctive or alternative therapy to NSAIDs and opioids. Gradual titration (“start low, go slow”) is important [11].

Literature:

- Guthrie B, et al: Adapting clinical guidelines to take account of multimorbidity. BMJ 2012; 345: e6341.

- Peters R, et al: Blood pressure and dementia: What the SPRINT-MIND trial adds and what we still need to know. Neurology 2019; 92(21): 1017-1018.

- Iadecola C, et al: Impact of Hypertension on Cognitive Function: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Hypertension 2016; 68: e67-e94.

- Kristensen RU, et al: Polypharmacy and Potentially Inappropriate Medication in People with Dementia: A Nationwide Study. J Alz Dis 2018; 63: 383-394.

- Clague F, et al: Comorbidity and polypharmacy in people with dementia: insights from a large, population-based cross-sectional analysis of primary care data. Ageing 2017; 46: 33-39.

- Nørgaard A, et al: Psychotropic polypharmacy in patients with dementia: prevalence and predictors. J Alzheimers Dis 2017; 56(2): 707-716.

- American Geriatric Society: American Geriatrics Society 2015 Updated Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2015; 63(11): 2227-2246.

- O’Mahony D, et al: STOPP/START criteria for potentially inappropriate prescribing in older people: version 2. Ageing 2015; 44(2): 213-218.

- Holt S, Schmiedl S, Thürmann PA: Potentially inadequate medication for the elderly. The PRISCUS list. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2010; 107(31-32): 543-551.

- Erdal A, et al: Analgesic treatments in people with dementia – how safe are they? A systematic review. Expert Opin Drug Saf 2019; 18(6): 511-522.

- Cravello L, et al: Chronic Pain in the Elderly with Cognitive Decline: A Narrative Review. Pain Ther 2019; 8(1): 53-65.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2019; 17(5): 26-28 (published 8/29/19, ahead of print).