Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) is often a major challenge not only for those affected, but also for physicians. Despite numerous therapeutic options, treatment is usually a tightrope walk between dangerous autoimmune activity and side-effect-laden immunosuppression. The current guidelines serve as a support for optimal therapy. Thanks to newly approved drugs, the limits of guideline therapy can be expanded.

SLE is a multi-organ disease with a multifaceted presentation. Typically, the disease runs a relapsing course. Getting these episodes of illness under control is not always easy. Nevertheless, if possible, the aim should be to achieve the lowest possible level of disease activity. This is because recurrent relapses cause irreversible damage, which is associated with a poor prognosis. But how can disease activity be curbed?

Assessment of disease acitivity

Systemic Lupus Erythematosus is, as its name implies, systemic. Therefore, various clinical scores that map multiple organ systems are primarily used to assess disease activity. The SLEDAI, BILAG, SLAM, LAI, and ECLAM are all reliable and functional scores for assessing lupus activity. However, the current EULAR (European Alliance Of Associations For Rheumatology) guidelines primarily use the SLEDAI and the BILAG, which is why we briefly explain these two scores here [2].

- The SLEDAI (Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Disease Activity Index) as well as its modification, the SELENA-SLEDAI, consist of 24 weighted laboratory values and clinical findings. The SLEDAI is probably the most user-friendly score and has a maximum value of 105 [3]. It is ideal for use in the clinical setting.

- The BILAG assesses clinical disease activity in eight organ systems, integrating a total of 86 statements. Each organ is assessed individually and divided into categories A to E. A describes a very high disease activity in the corresponding organ, D a stable disease course and E means that the organ has never been affected by lupus. Numbers are then assigned to the alphabetical rating: A = 9, B = 3, C = 1, D = 0, E = 0. Thus, the overall activity of the SLE can be estimated. The maximum value is 72. For monitoring a new disease episode, the BILAG is more sensitive than the SLEDAI. However, the BILAG is relatively cumbersome to collect and is therefore more suitable for study purposes [3].

Current guidelines divide SLE disease activity into 3 categories. Simplified, this classification can be made using the scores just explained.

- Mild: SLEDAI ≤6; ≤1 BILAG B

Manifestations - Moderate: SLEDAI 7-12; ≥ 2 BILAG B

Manifestations and - Heavy: SLEDAI > 12; BILAG A

Manifestations

Current guidelines for SLE treatment

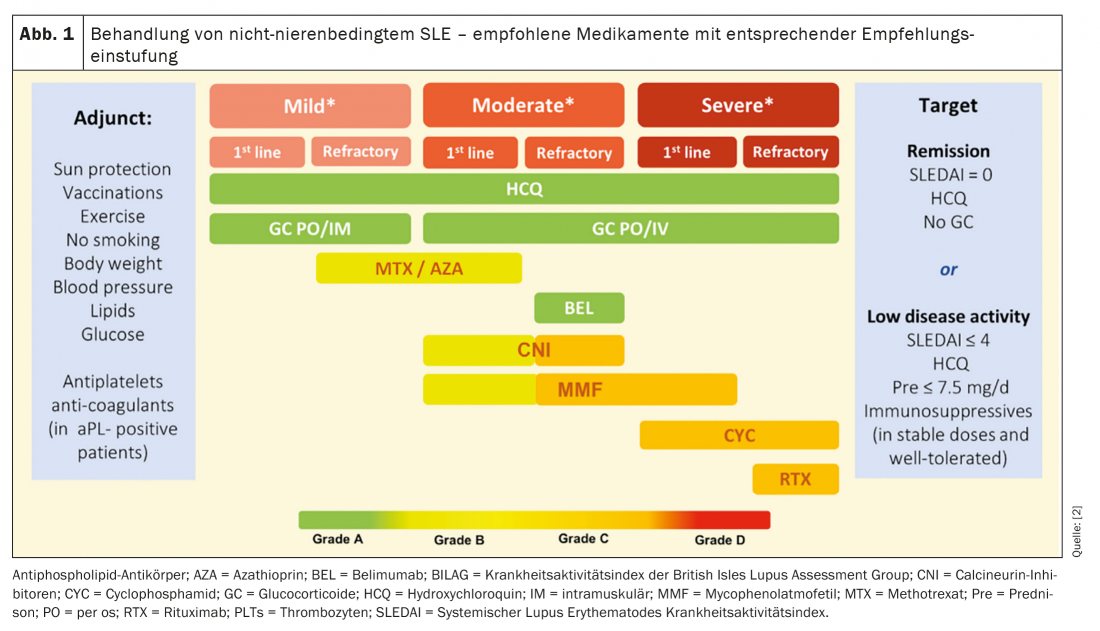

SLE therapy follows a sophisticated stepwise regimen according to the disease activity of the affected person (Fig. 1) . The goal is remission of SLE or at least the achievement of low disease activity (LDA). To this end, since 2019, all patients with active lupus have been recommended to receive hydroxychloroquine therapy. Previously, hydroxychloroquine was indicated only for patients with mild to moderate manifestations. For hydroxychloroquine, 5 mg/kg body weight should not be exceeded due to retinotoxicity from long-term use. This leads to heated minds as the efficacy of hydroxychloroquine has been demonstrated at a dose of 6.5 mg/kg body weight. Nevertheless, it undoubtedly forms the first line therapy. In addition, the therapy of a relapse always includes glucocorticoids. However, these should reach no more than a maximum dose of 7.5 mg/d prednisone equivalent for long-term administration and should be discontinued whenever possible. Helpful in the reduction of steroid therapy is the initiation of immunomodulatory therapy [2]. In addition, belimumab may now be administered in refractory courses, which will be discussed in more detail below.

New drugs

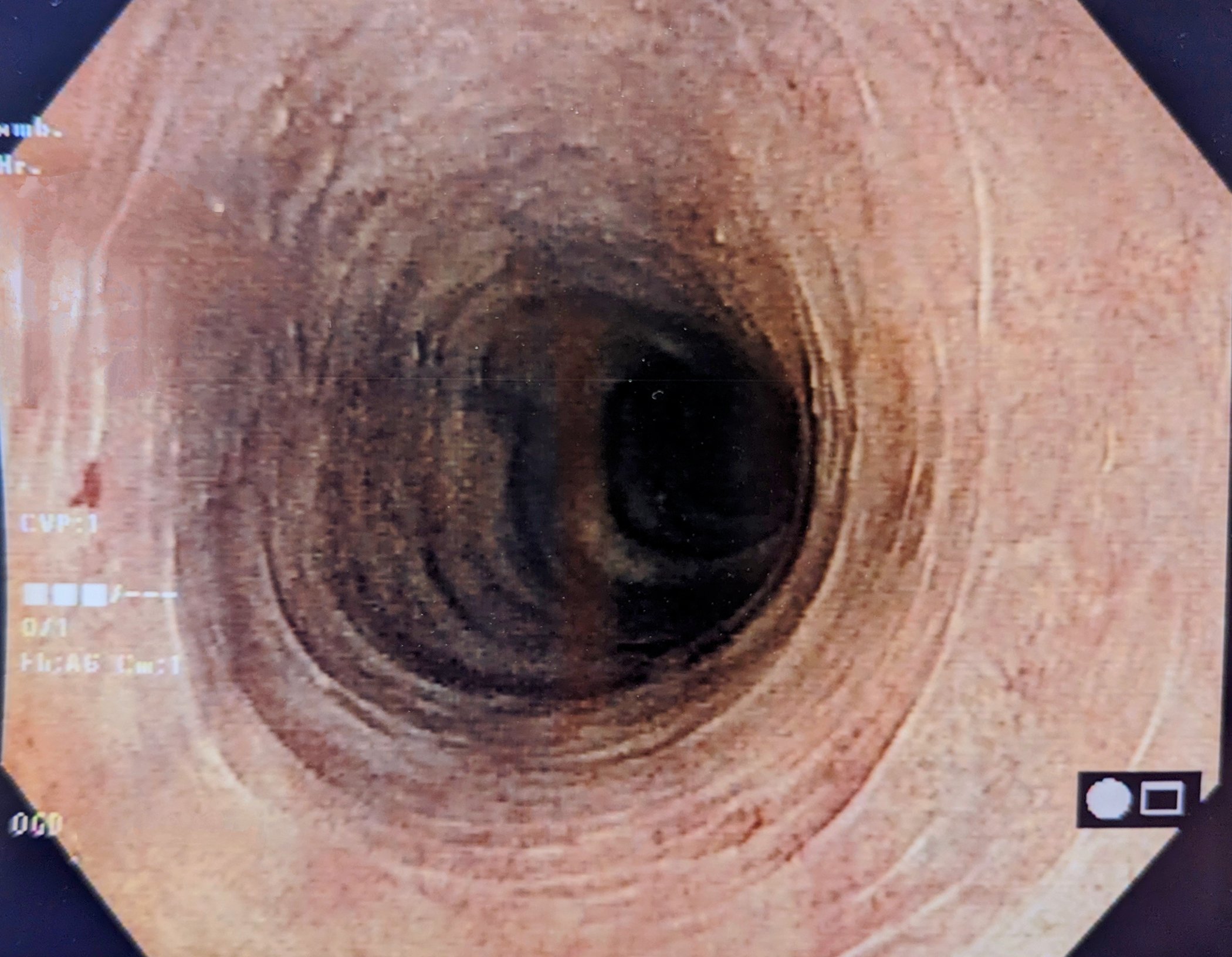

In the following, we briefly discuss three drugs for which important studies have been published since the publication of the EULAR guidelines. Therefore, the therapies are not yet integrated into the currently applicable guidelines. However, they are of particular interest for the treatment of lupus nephritis. This lupus manifestation is currently treated as second line therapy in addition to established systemic lupus therapy with known calcineurin inhibitors such as tacrolimus or cyclosporine.

Anifrolumab (Saphnelo)

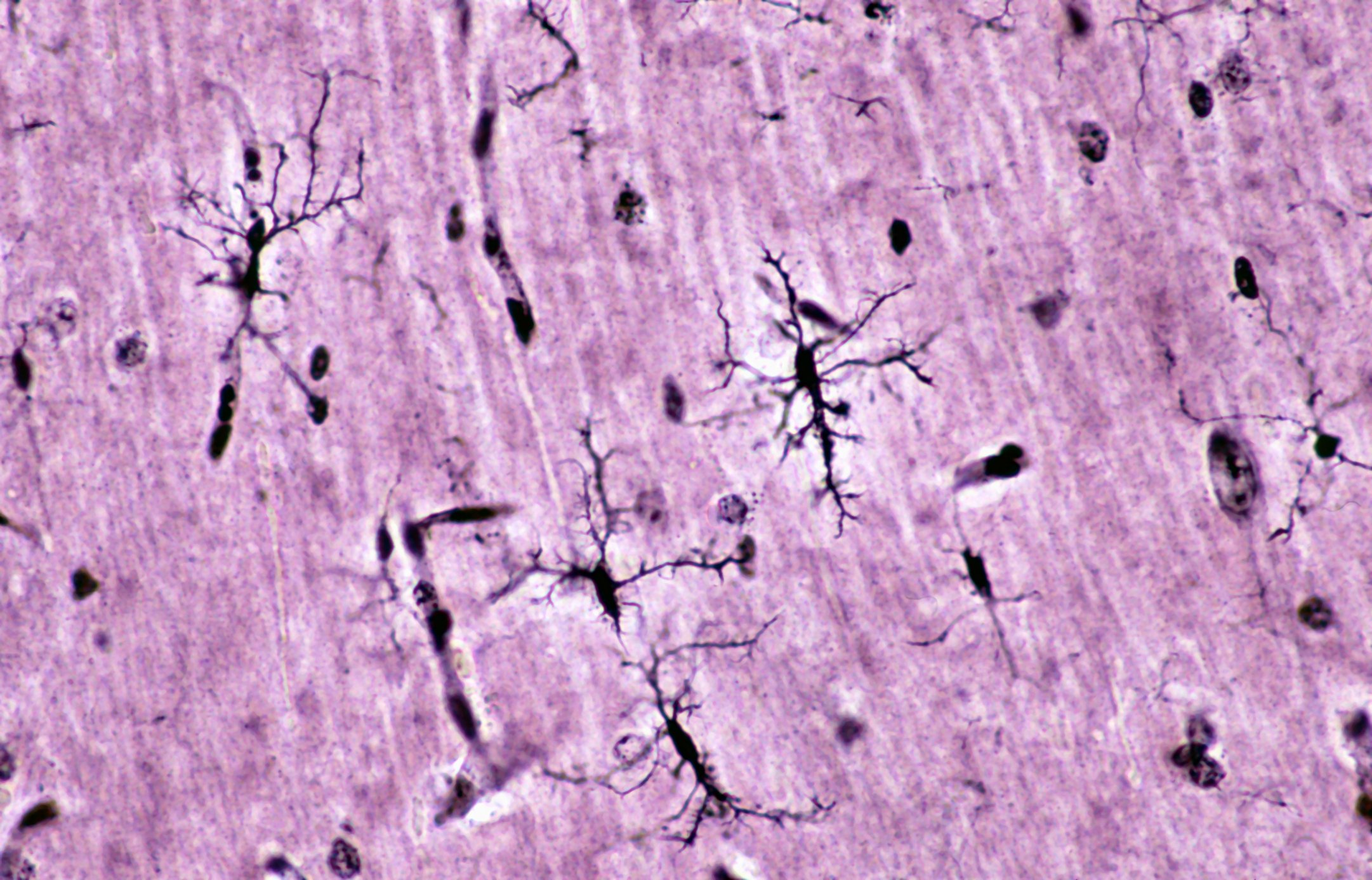

Anifrolumab is a monoclonal antibody that inhibits the type 1 interferon receptor on macrophages and NK cells. Thus, it attenuates the effect of IFNα and other type 1 interferons, which are significantly involved in the pathogenesis of SLE.

Anifrolumab was administered as add-on therapy to standard of care therapeutic regimens with hydroxychloroquine, glucocorticoids, and immunomodulators. The primary endpoint in the Phase III TULIP-2 study was a singificant improvement in BICLA (BILAG-Based Composite Lupus Assessment). Already after the first eight weeks a significant effect could be detected compared to the placebo group. Also, except for an increased incidence of herpes zoster, there were no additional side effects. Consequently, anifrolumab was approved by the FDA last year for moderate and severe lupus manifestations. EMA approval is still pending.

Belimumab (Benlysta)

Belimumab is a monoclonal antibody that inhibits BLyS (B lymphocyte stimulating factor) . BLyS is normally produced by monocytes and neutrophils.

Belimumab was already approved by the FDA and the EMA for SLE therapy in 2011. However, it was not until 2020 that the BLISS-LN trial demonstrated the efficacy of belimumab against lupus nephritis. The primary endpoint was partial renal response with a uPCR ≤0.7 (urinary protein creatinine ratio). Secondary endpoint was complete renal response (uPCR ≤0.5). The primary and secondary endpoints were met by 10 percent more subjects after 104 weeks. Later phase IV studies even showed improved renal response in over 20 percent of subjects.

Voclosporin (Lupkynis)

Voclosporin is a cyclosporine analog. Like cyclosporine, voclosporin inhibits calcineurin. Thus, voclosporin decreases interleukin-2 production, which is important for the T-cell mediated immune response. Voclosporin is not only more potent than cyclosporine, but also has a greater therapeutic breadth. This increased safety of voclosporin obviates the need for dose monitoring, which is common with cyclosporine use. Further, voclosporin stabilizes the actin cytoskeleton of renal podocytes. This supports the function of the basement membrane.

The Phase III Aurora 1 study evaluated efficacy against lupus nephritis. The primary end point was complete renal response, and the secondary end point was partial renal response. After 52 weeks, therapy with voclosporin in combination with mycophenolate mofetil and low-dose glucocorticoids showed a higher rate of complete renal response. The side effect profile was comparable to that of the placebo group. Accordingly, voclosporin was approved by the FDA in 2021. An EMA approval is still pending. Voclosporin is preferable to belimumab for lupus nephritis with high proteinuria. If in lupus nephritis, rather the nephritic component is present, therapy with belimumab is recommended.

Treat-to-target strategy

The overall goal of SLE therapy is remission without continuous medication in addition to hydroxychloroquine. Patients benefit most from a targeted treatment strategy. This treatment strategy is divided into three steps as listed in Figure 2. When remission is achieved, the goal should be to stop glucocorticoids and later to stop immunomodulators. If the patient has achieved only profound disease activity and no remission at baseline, gradual reduction of glucocorticoids and immunomodulators is recommended. Fortunately, the effective therapeutic agents help so well that in the vast majority of cases an acute attack can be stopped. The much bigger problem is the long-term control of disease activity. Therefore, between treatment steps, lupus activity must be monitored every four to six months. In this way, a relapse can be detected at an early stage during the reduction in therapy. This is particularly important because a lot of organ damage occurs, especially at the beginning of a relapse. Thus, after 6 months of lupus activity, irreversible damage is already evident in about one fifth of patients. The two prognostically relevant factors that have a protective effect on the further course of the disease are, on the one hand, a long duration of remission and, on the other hand, the accumulated duration of hydroxychloroquine use. However, it is often only a matter of time before the next relapse occurs. Thanks to the novel mechanisms of action of the newly approved drugs, there is at least some hope that remission periods will last longer in the future.

Congress: SSAI

Literature:

- Andrea Doria (Padova IT), New Strategies in the Management of SLE, SSAI Conference Jan. 28, 2022.

- Fanouriakis A, Kostopoulou M, Alunno A, et al: 2019 update of the EULAR recommendations for the management of systemic lupus erythematosus. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2019;78:736-745.

- Lam GK, Petri M: Assessment of systemic lupus erythematosus. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2005 Sep-Oct; 23(5 Suppl 39): S120-132.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2022; 17(6): 24-25