Voice disorder is a commonly cited symptom in family practice. In addition to other differential diagnoses, acute laryngitis is a possible cause. Antibiotics are not indicated here, but voice rest and treatment of symptoms help. The following article provides an overview of possible therapeutic strategies.

Cohen [1] published a retrospective analysis of a large state health data collection in 2012. The most common causes of laryngeal disorders with the main symptom of dysphonia were as follows (in order of frequency):

- Acute laryngitis

- Non-specific (functional) dysphonia

- Benign vocal fold lesion (e.g. polyp)

- Chronic laryngitis

Acute laryngitis is caused by viral, rarely bacterial infections, but may also be allergic or toxic (inhalation trauma). Chronic laryngitis, on the other hand, characterized by a prolonged history, may arise from acute laryngitis, due to noxious agents (tobacco in the first place), allergies, in the context of chronic rhinosinusitis (“syndrome descendent”), or gastroesophageal reflux [2, 3]. The primary care physician usually does not have the capability of diagnostic loupe laryngoscopy and therefore must work mainly with the history and general medical status. Therefore, a differential diagnosis will be pointed out, based on the medical history.

Symptomatology

Primarily, a distinction must be made between short- and long-term voice disorders, where short-term means one to three days, and long-term means weeks to months or even years.

Short-term voice disorder

In the case of a short-lasting, i.e. acute, voice disorder, acute laryngitis is most likely to be present. If, in addition to the voice disorder, other symptoms are present that are indicative of a viral infection of the upper respiratory tract, such as rhinitis, sore throat, difficulty swallowing, cough and general feeling of illness, it is very likely that the patient has acute viral laryngitis. Dysphonia may also occur as an isolated symptom in this disorder, although rarely.

Differential diagnosis: Only the following three diagnoses can be considered:

- Vocal fold paralysis due to damage to the recurrent nerve for idiopathic or mechanical reasons (e.g., thyroid carcinoma, aortic aneurysm, bronchus carcinoma) may also occur very suddenly and occasionally be accompanied by cough, but is characterized by marked breathy voice and markedly altered cough sound. This disruption lasts longer than would be expected with acute inflammation. The patient must therefore be laryngoscoped and, if necessary, referred for further evaluation.

- The functional or psychogenic dys- or aphonia , a conversion neurotic disorder, which could also be called functional apraxia of the vocal apparatus, usually occurs without a clearly apparent cause [4]. It is often an expression of a basic psychopathological constellation (aggression inhibition), but can also be triggered by conditions in which proprioception in the vocal tract is altered, e.g., by acute laryngitis. It is often interpreted by the patient himself as an infection, which can be misleading. This disorder can also last for weeks to months and must be clarified in this case and, above all, logopedically treated in order to avoid a fixation of the disorder.

- Vocal fold hemorrhage may occur due to altered vascular fragility, e.g., for hormonal, inflammatory reasons or in the event of additional malabsorption. As with other hematomas, resorption of the blood occurs within a few days.

Thus, the diagnosis of acute laryngitis can and may be made virtually on the basis of the medical history (Table 1).

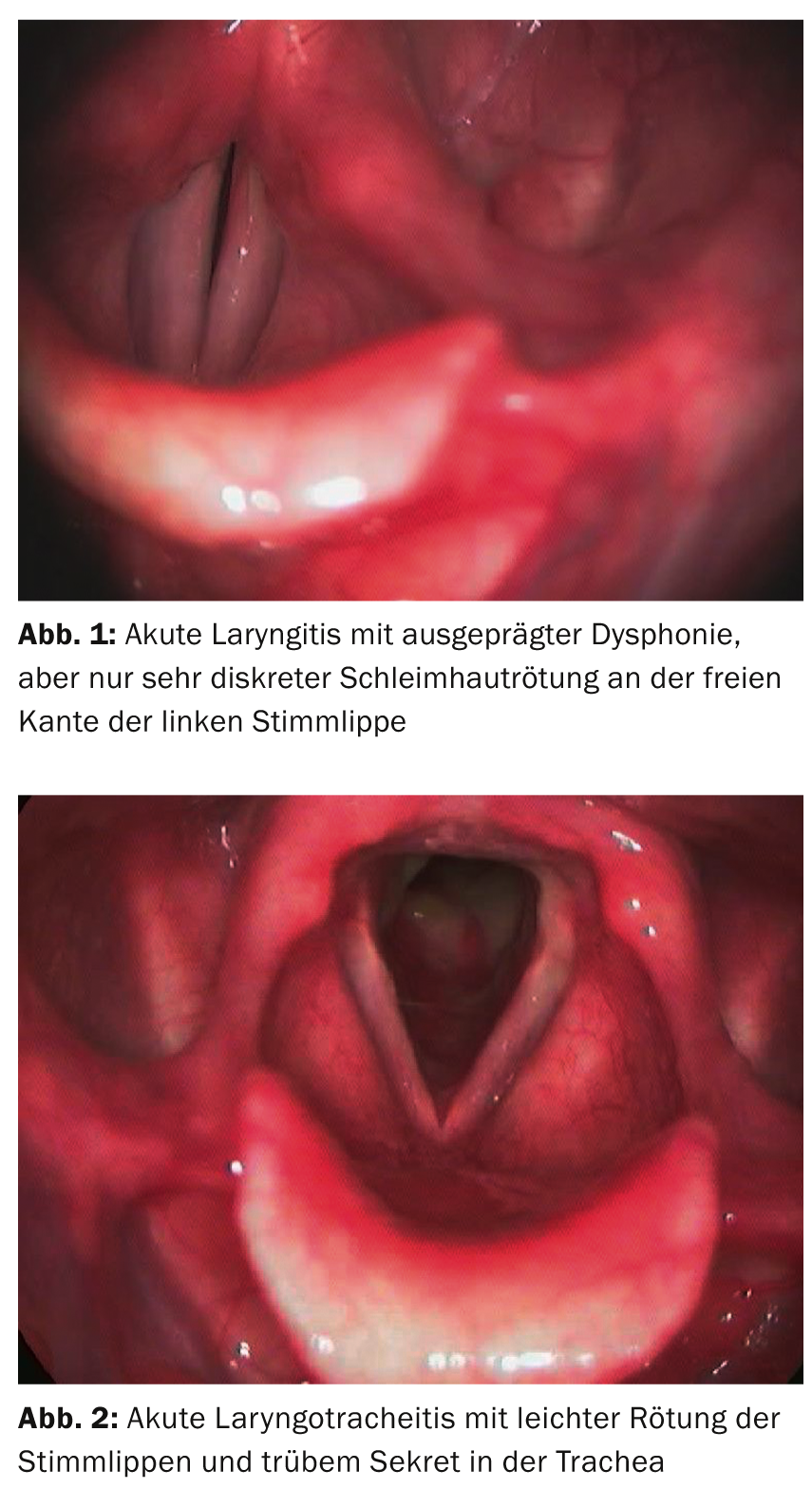

The pathology of acute laryngitis (Figs. 1 and 2): Catarrhal laryngitis is characterized by inflammatory mucosal edema. In addition, there is sometimes a mucopurulent secretion. The often not very conspicuous finding (a reddening is sometimes hardly recognizable) often massively changes the mechanics at the glottis (at the tone generator). The mucosa loses its suppleness and can only be made to vibrate with increased blowing pressure. This requires a stronger glottis closure, which causes muscular overload in the larynx during prolonged speech. When the edema becomes so pronounced that no vibration is possible even with the strongest glottis closure and an increase in blowing pressure, the dysphonia becomes aphonia.

Therapy: Causal therapy of acute viral laryngitis is not possible. Symptomatically, various medications that can also be used otherwise for upper respiratory tract infections can be helpful. Inhalation with warm steam often proves pleasant and is mildly virostatic. Various substances can be added, and essential oils can have a drying effect.

Since the production of viscous mucus interferes with glottic function, the prescription of acetylcysteine is useful.

Concurrent cough means an additional increase in glottic stress, so cough medications should be used generously (codeine).

NSAIDs are often administered for their decongestant effect, but this is extremely low on the vocal folds. However, these drugs cause better proprioception, thus reducing the risk of reactive hyperfunction.

When a voice needs to be improved very quickly for valid reasons, steroids can be used. Inhaled steroids show little effect and tend to be drying. Depending on the situation, a single dose of, for example, 50-100 mg prednisone or 3 mg betamethasone can be delivered by os. The effect on the voice occurs after about five to six hours and subsides within about 24 hours, i.e. the voice disorder returns depending on the pre-existing severity. In case of florid infection, it is useful to perform antibiotic shielding at the same time.

A 2008 publication from the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence [5] shows that in England and Wales, 25% of consultations with a generalist are for an upper respiratory tract infection, and this is the reason for antibiotics in 60%. In Switzerland, this may be different, but some considerations about antibiotic therapy are certainly useful. A study by Reveiz 2007 [6] showed that penicillin showed no benefit over placebo in an upper respiratory tract infection; with therapy with erythromycin, dysphonia and cough subjectively lasted less time, but this could not be objectively verified. So antibiotics are not indicated in viral laryngitis, but if something does need to be given in a very specific situation (e.g., need for steroid delivery), macrolides, e.g., acithromycin, are a good option.

Very important, on the other hand, is the silence of the voice. It does not necessarily have to be absolute in every case, but the use of voice must at least be clearly restricted. The extremely unfavorable physical conditions at the glottis lead to tension of the laryngeal muscles and thus to hyperfunction in the longer term. There is also a risk of transition to chronic laryngitis if the inflamed vocal folds are forced. Especially in the case of patients in speech professions, it is therefore essential to certify that they are sufficiently incapacitated for work.

Prolonged voice disorder

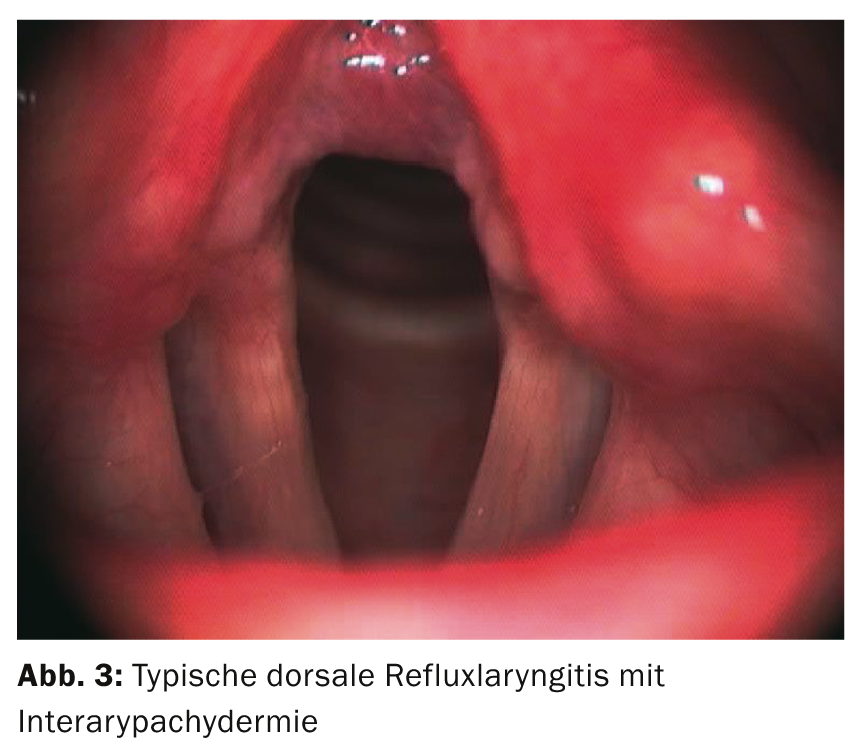

A voice disorder that persists for longer than three weeks can have very many causes (such as the frequent reflux laryngitis, which can be treated very well probatorily with PPI, cf. Fig. 3) and must be clarified laryngoscopically in the absence of improvement, primarily for early detection of laryngeal carcinoma.

But even a harmless voice disorder can be an unexpectedly big problem for the patient, because not only the changed voice sound, but above all the increased effort necessary for phonation leads to great suffering.

Functional, but also many organic voice disorders can be improved by voice therapy or minor surgery.

Salome Zwicky, MD

Literature:

- Cohen SM, et al: Prevalence and causes of dysphonia in a large treatment-seeking population. Laryngoscope 2012; 122: 343-348.

- Nawka T, Wirth G: Voice disorders: Textbook for Physicians, Speech Therapists, Speech-Language Pathologists and Speech Scientists. 5th, completely revised ed. Deutscher Ärzte-Verlag; 2007.

- Wendler J, et al: Lehrbuch der Phoniatrie und Pädaudiologie. Georg Thieme Verlag; 2005.

- Zwicky S, et al: Phoniatric and psychological follow-up in psychogenic aphonia. ORL: Current Problems in Otorhinolaryngology 1995;19:272-278.

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (UK): Respiratory Tract Infections – Antibiotic Prescribing: Prescribing of Antibiotics for Self-Limiting Respiratory Tract Infections in Adults and Children in Primary Care[Internet]. 2008. Available from: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21698847 [zitiert 2012 Mai 25]

- Reveiz L, et al: Antibiotics for acute laryngitis in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007;(2):CD004783.

CONCLUSION FOR PRACTICE

- The rapid-onset voice disorder is most likely caused by acute laryngitis.

- Antibiotic therapy for acute laryngitis is not indicated.

- Voice sparing in acute laryngitis is important for preventing chronicity of the infection or secondary hyperfunction.

- If the voice disorder lasts longer than three weeks, it must be clarified laryngoscopically.

A RETENIR

- La dysphonie soudaine est provoquée très vraisemblablement par une laryngite aiguë.

- Un traitement antibiotique n’est pas indiqué en cas de laryngite aiguë.

- Ménager sa voix lors d’une laryngite aiguë est important pour éviter une chronicisation de l’infection ou une hyperfonction secondaire.

- Si la dysphonie dure plus de trois semaines, une investigation par laryngoscopie s’impose.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2014; 9(3): 21-24