Short bowel syndrome (KDS) refers to a form of bowel failure that occurs postoperatively after extensive bowel resection or due to other functional limitation of bowel segments. Depending on the extent of limitation, other forms of nutritive supplementation are indicated. With the aid of specific nutrition therapy, some patients can be given the opportunity to resume autonomous oral feeding.

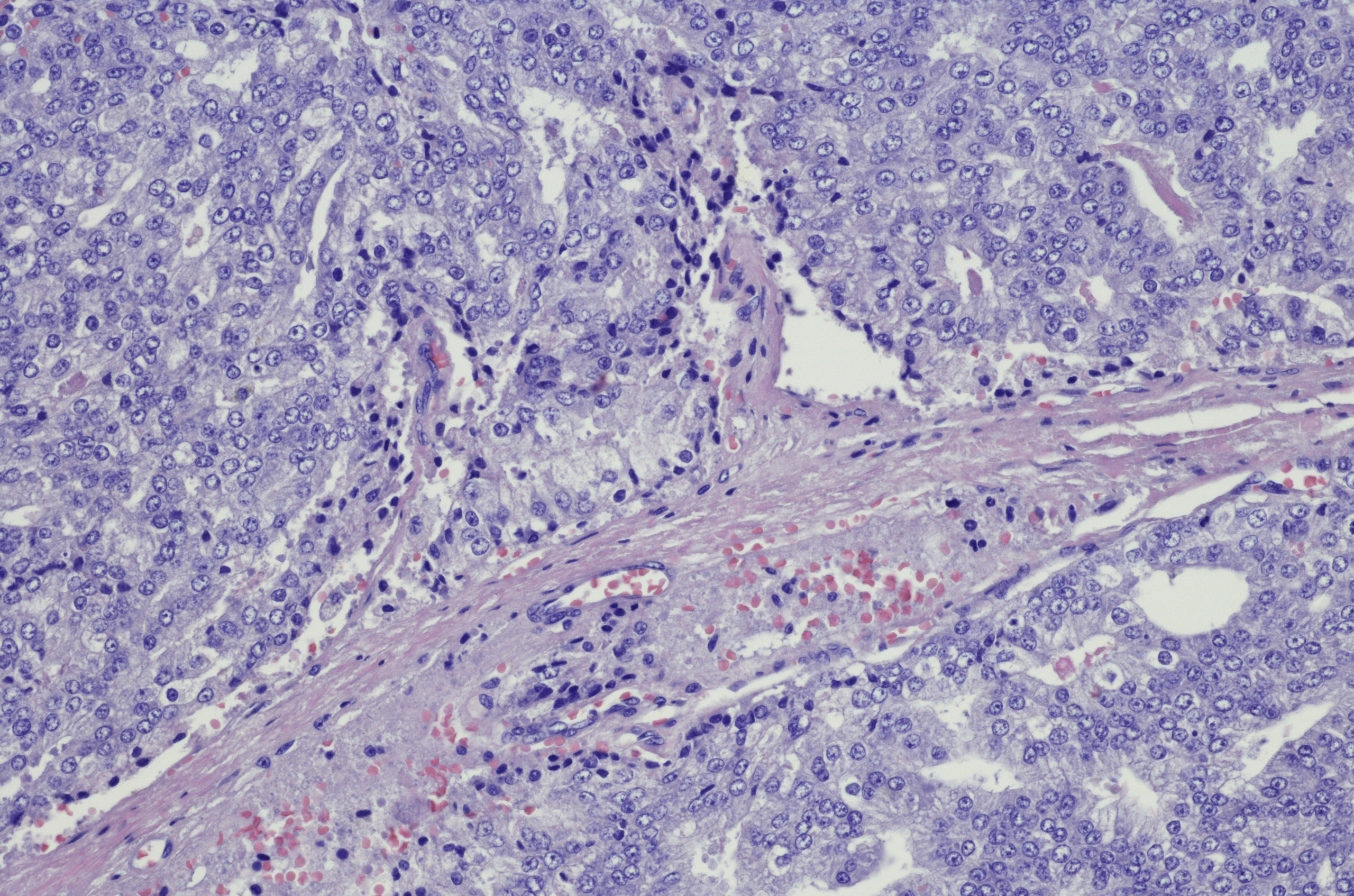

Short bowel syndrome is a rare, potentially life-threatening disease with an estimated prevalence of 34 per million population in Germany [1]. The current S3 guideline of the German Society of Nutritional Medicine (DGEM) defines intestinal failure as the inability to maintain protein, energy, fluid, and micronutrient balance due to impaired intestinal absorptive capacity (obstruction, dysmotility, congenital disease, disease-associated decreased absorption) [2]. Short bowel syndrome refers to a form of bowel failure that occurs postoperatively after extensive bowel resection or due to other functional limitation of bowel segments. The most common causes include carcinoma, mesenteric infarction, Crohn’s disease, and postoperative brides [3].

Clinically, KDS is indicated as soon as the length of the remaining bowel falls below 200 cm [4]. The extent of malnutrition and the individual symptoms depend on which section of the intestine is affected and to what extent, especially since different substances are absorbed depending on the section. Adaptive processes, the underlying disease, and comorbidity also have an influence [5].

Typing and nutritive supplementation

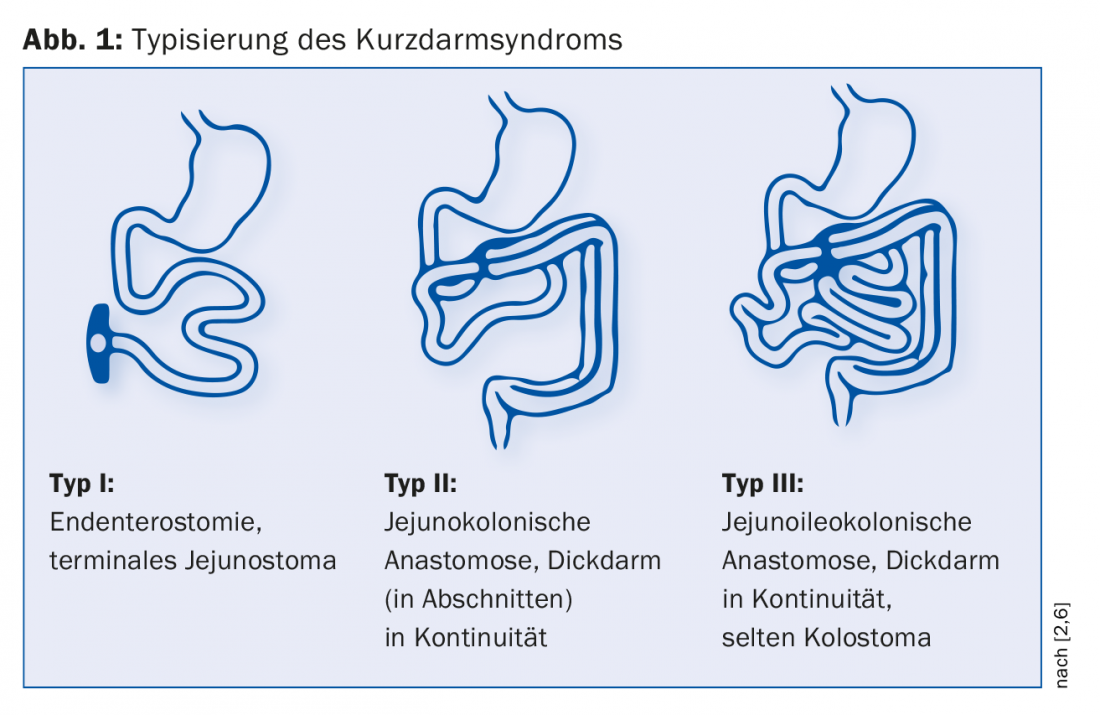

According to Messing, three types of postoperative KDS are distinguished (Fig. 1) [6]. Endenterostomy represents the most difficult case due to the absence of both ileum and colon. “There are big problems here, like dehydration with high stoma output,” Dr. Krieger-Grübel explains. Which type is present significantly influences the course of the disease: “If there is less than one meter of residual small bowel with a terminal small bowel stoma, patients are dependent on parenteral nutrition and saline solutions. In contrast, if they have more than one meter of small bowel available and the colon is present in continuity, they are unlikely to need supportive nutritional treatment in the long term.” The influence of residual bowel length on mortality was demonstrated in one study: After five years, the probability of survival of patients with colon in continuity was 30% greater than that of those with endenterostomy [6].

Phase-specific nutrition therapy

The primary goal is to ensure fluid and nutrient balance and prophylaxis of complications. Depending on the condition of the gastrointestinal tract, patients should also be enabled to resume autonomous oral feeding with appropriate therapy [7].

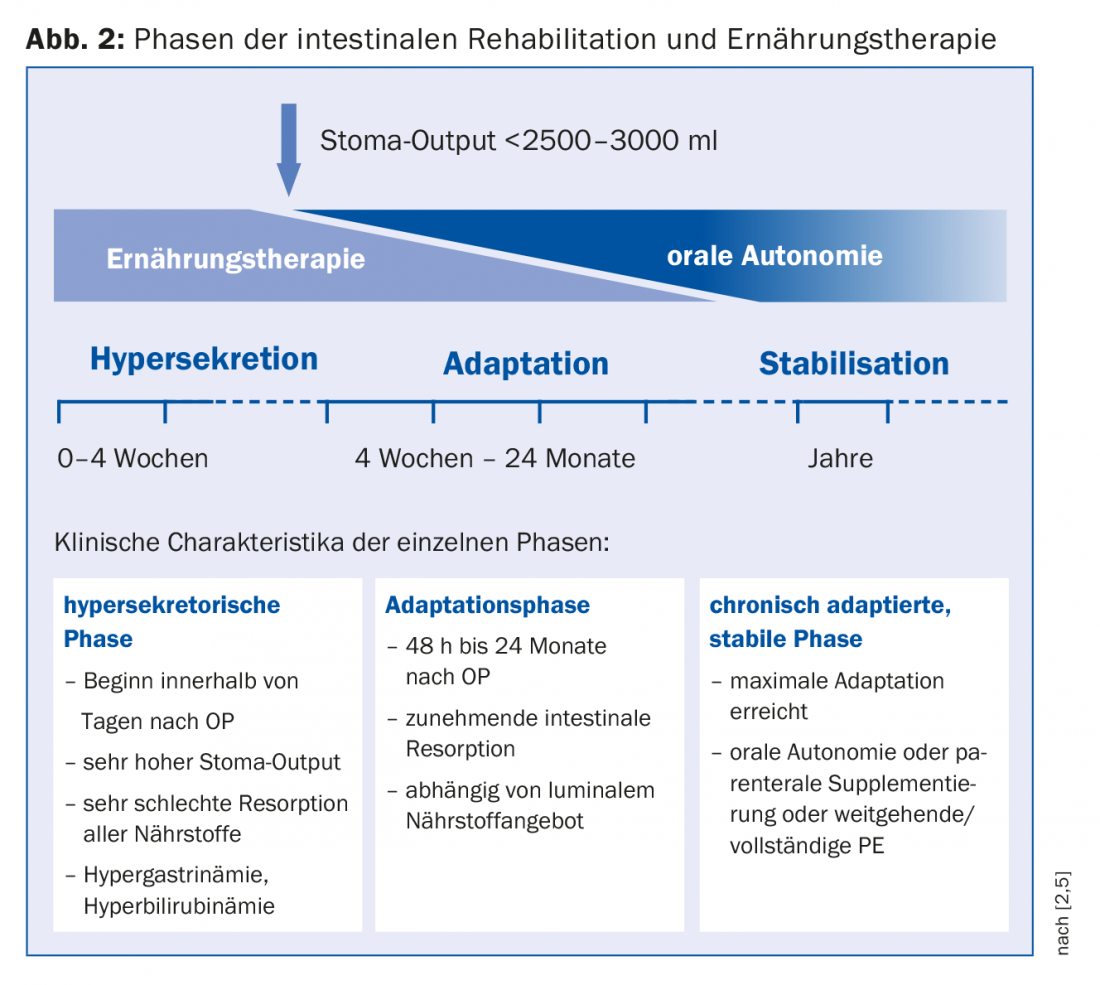

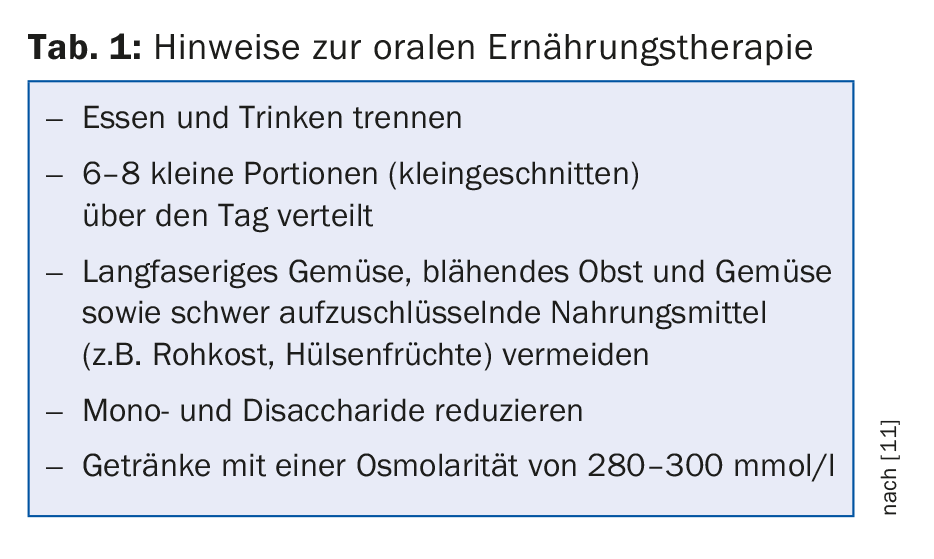

For therapy planning, a division into hypersecretion phase, adaptation phase and stabilization phase is suitable, whereby these phases merge into one another (Fig. 2) [1]. Each phase requires a specific nutritional strategy. Immediately after surgery, hypersecretion occurs initially in the form of high-output stoma and diarrhea. Here, parenteral nutrition (PE) is inevitable due to malabsorption of all nutrients. Monitoring fluid homeostasis is central. To check the hydration status (15 ml of fluid/kg body weight is needed to excrete urinary substances), sodium is suitable as a sensitive parameter, and an amount of >20 mmol/l is considered sufficient. When stoma output could be reduced (<2500-3000 ml), oral feeding can be started. “Enteral nutrition is the actual trigger of cell proliferation,” Dr. Krieger-Grübel emphasized. It leads to cell growth as well as an increase in villi and, through increased intestinal blood flow, improved absorptive capacity. However, since a higher energy demand is to be expected in principle, PE must not be stopped at an early stage [8]. Recommendations for oral nutrition therapy during the adaptation phase are summarized in Table 1. “For rehydration, a combination of sodium and glucose is eminently important because glucose uptake into the cell is sodium-coupled.” Liquids must therefore be salted. To a 1:3 diluted apple juice would then come just under 5 g salt (1 tsp), which corresponds to about 100 mmol. In case of malabsorption of fats, administration of medium-chain fatty acids is indicated if the colon is preserved. Further complications in preserved colon, such as kidney stones, can be prevented by an increased intake of calcium, which is responsible for binding oxalate, and by a principled reduction of oxalate-containing foods.

Medication

The aim of pharmaceutical measures is to reduce secretion and slow down motility. Antisecretory effect, for example. Proton pump inhibitors, which inhibit H+/K+-ATPase in the vestibular cell, or somatostatin analogs. Octreotide, for example, slows down various peptides, hormones, and pancreatic secretion, but also leads to a reduction in blood flow and food absorption.

Loperamide is used first to counteract increased motility. If the effect is too small, opium tincture can be given afterwards. Loperamide and opium tincture achieve their effect by stimulating the gastrointestinal opioid receptors. Propulsive motility is blocked, resulting in increased fluid reabsorption, decreased secretion, and increased tone in the anal sphincter [9]. Other drug options include cholestyramine (chologenic diarrhea with colon in continuity), pancreatic enzymes in steatorrhea, and soluble fibers to provide additional binding of intestinal fluid. A new study shows an effect of teduglutide in patients without a colon and with a stoma: in this group of patients, parenteral fluid intake was reduced by 40%, while the placebo group achieved only a 19% reduction; in contrast, there was no effect in patients with a colon in continuity [11].

Source: SGAIM Spring Congress, May 30-June 1, 2018, Basel

Literature:

- Websky MW, et al: The short bowel syndrome in Germany. Estimated prevalence and care situation. Surgeon 2014; 85(5): 433-439.

- Lamprecht G, et al: S3-Leitlinie der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Ernährungsmedizin e.V. in Zusammenarbeit mit der AKE, der GESKES und der DGVS. Clinical nutrition in gastroenterology (part 3) – chronic intestinal failure. Current Nutritional Medicine 2014; 39(2): e57-e71.

- Krafft T, et al: Long-term outcome in chronic intestinal failure: characteristics, prognosis, and complications. Z Gastroenterol 2013; 51: K285.

- Pironi L, et al: ESPEN guidelines on chronic intestinal failure in adults. Clinical Nutrition 2016; 35(2): 247-307.

- Karber M, et al: Chronic intestinal failure and short bowel syndrome. Home parenteral nutrition (HPE) compendium. Guidelines KDS Charité Berlin. 2015.

- Messing B, et al: Long-term survival and parenteral nutrition dependence in adult patients with the short bowel syndrome. Gastroenterol 1999; 117(5): 1043-1050.

- O’Keefe SJ, et al: Short Bowel Syndrome and Intestinal Failure: Consensus Definitions and Overview. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006; 4: 6-10.

- Leuenberger M, et al: The short bowel syndrome: an interdisciplinary challenge. Current Nutritional Medicine 2006; 31: 235-242.

- Dorfschmid M, Sinik-Agan C: Intestinal failure – nutritional therapy in short bowel syndrome. Schw Z Ernährungsmed 2017; 1: 10-18.

- Jeppesen PB, et al: Factors Associated With Response to Teduglutide in Patients With Short-Bowel Syndrome and Intestinal Failure. Gastroenterol 2018; 154(4): 874-885.

- Matarese LE: Nutrition and fluid optimization for patients with short bowel syndrome. JPEN 2013; 37(2): 161-170.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2018; 13(7) – published 8.6.18 (ahead of print).