A geriatric assessment optimizes health status assessment and provides a basis for oncology treatment decisions. Oncological therapies for localized and advanced tumor stages have evolved considerably in recent years, expanding the treatment spectrum also for elderly patients. The decision for oncological therapy should be made in an institution with experienced specialists, after adequate information of the patient and his relatives, and taking into account the benefit-risk profile.

Even if tumor-directed treatments are abandoned, palliative measures are available that can contribute to a better quality of life for the elderly tumor patient.

Cancers predominantly affect people in older age. Because of increasing life expectancy, cancer has become a clinical everyday problem. In recent years, significant advances have been made in treatment modalities; for example, targeted therapy has entered the oncology treatment toolbox on a broad front. These advances are associated with increasing differentiation and complexity of treatments.

Traditionally, oncologic therapies have been established in fit and majority younger patients, so there is a lack of good data for treating older patients. However, in recent years, awareness of elderly and comorbid patients has grown, so that they are increasingly included in studies and studies are also being conducted specifically for this patient group. This provides hope for evidence-based improvements in the quality of care for older patients in the future.

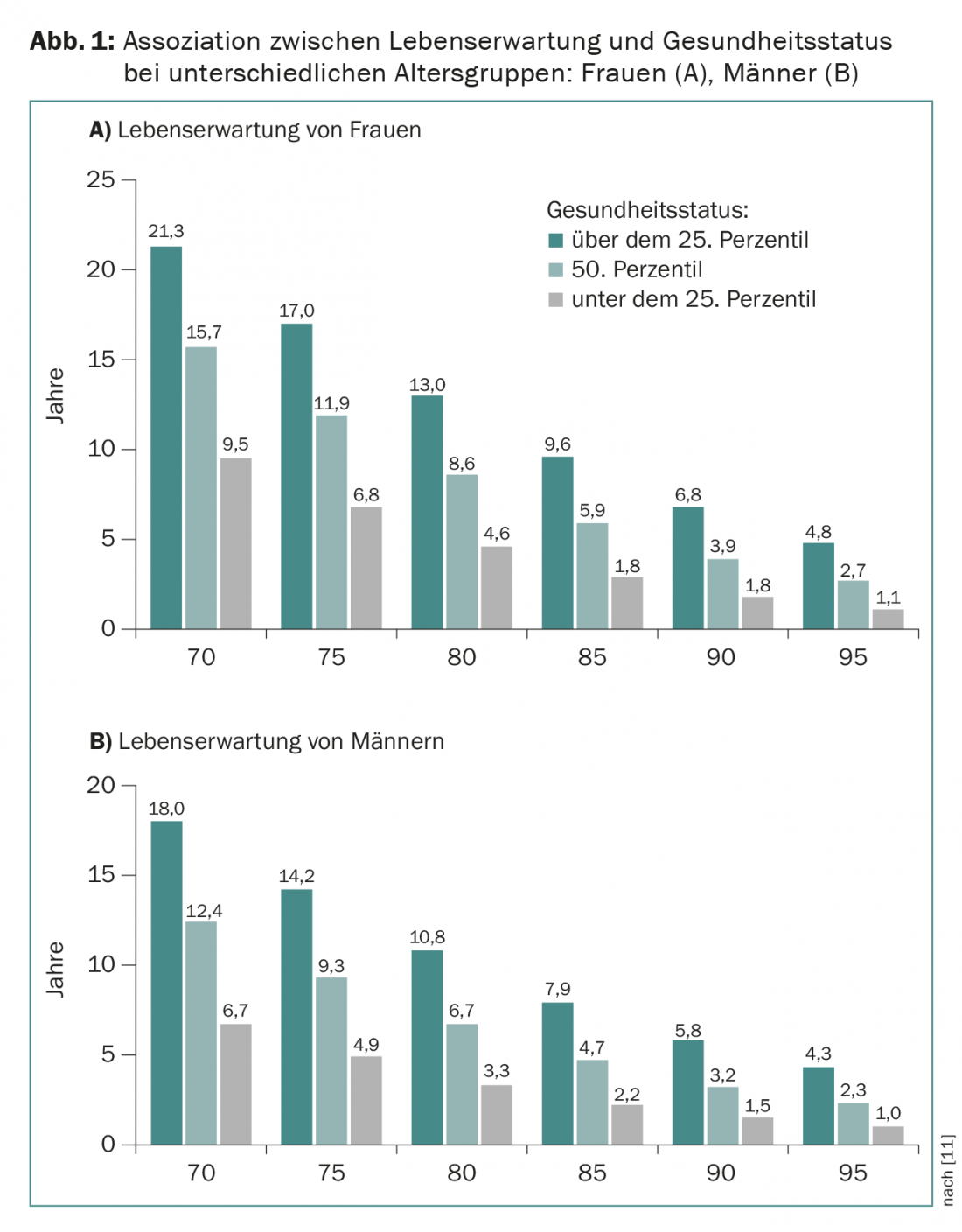

The main problem in recording the elderly patient is the great heterogeneity in health status, which is determined less by chronological age than by comorbidities. For example, a healthy 75-year-old has a life expectancy of just over 14 years, and a healthy 75-year-old has a life expectancy of as many as 1-7 years, compared to less than five years for a frail 75-year-old (Fig. 1).

Recording the health status of elderly patients is not always easy and is usually not done in a structured way. In addition to the great physical variability, the changed therapy goals must also be taken into account: Often, the focus is no longer on prolonging life, but on maintaining quality of life. The great challenge is to develop a tailor-made concept based on the patient’s constitution, the patient’s wishes and the available therapy options, so that both under- and overtherapies are avoided.

The first part of this article will focus on the assessment of elderly patients, and the second part on specific aspects of common oncologic diseases.

Geriatric assessment

Assessment of the geriatric patient is often based on the clinician’s gut feeling, and crucial issues may be overlooked. The goals of a structured assessment are to obtain a comprehensive picture of health status to identify areas amenable to geriatric intervention (e.g., addressing malnutrition or improving mobility) and to obtain a prognostic assessment of the patient. The information provided by the assessment can significantly influence the choice and intensity of oncologic treatment [1].

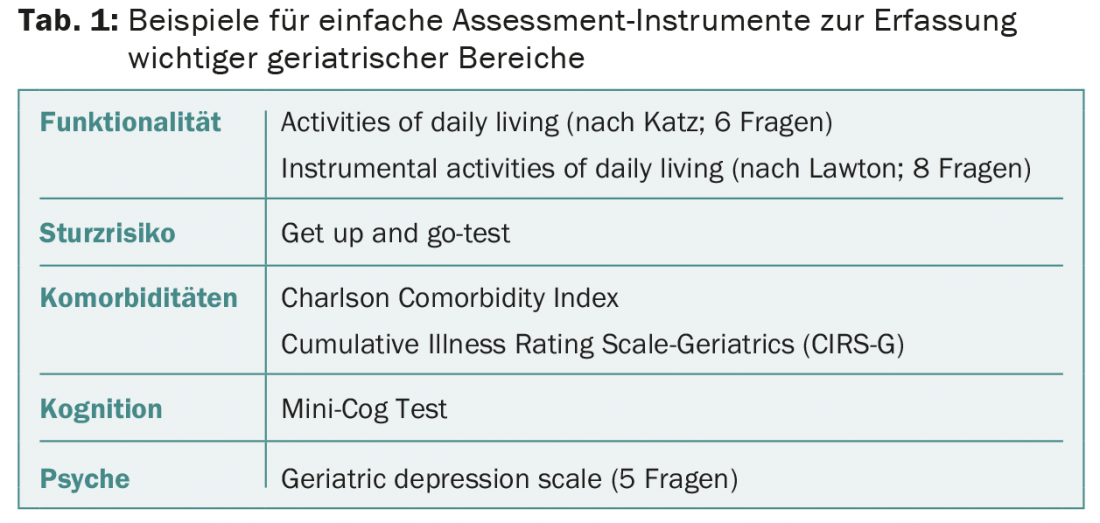

The main areas to be assessed are functionality and mobility, comorbidities, psyche and cognition, the social situation, and the patient’s nutritional status. In addition, medication should be reviewed to detect any polypharmacy. Simple and validated assessment instruments are available for the individual areas, which can be carried out with limited time expenditure (Tab. 1) . In the case of abnormalities or situations that are difficult to assess, it is advisable to consult a geriatrician who will perform a comprehensive geriatric assessment.

Brief screening instruments such as the G8 (8 questions) or the VES-13 (13 questions) cannot replace a detailed assessment, but are helpful in identifying patients who need a more detailed evaluation when time resources are limited [2]. Several components of the geriatric assessment (especially functional activities, nutritional status, and comorbidities) show a good association with patient survival and allow estimation of prognosis, independent of the underlying oncologic disease. It has also been shown that geriatric assessment scores correlate with the incidence of severe treatment toxicities. Specific assessments to predict chemotherapy tolerability are currently under development. However, due to the heterogeneity of oncological diseases and the multitude of oncological therapies, practical aids are not expected in the foreseeable future.

In principle, the elderly patient and his relatives should be adequately informed and involved in the treatment process. Specifically, the prognosis of the disease and treatment options should be clearly communicated so that a joint risk-benefit assessment can be made.

Prostate Cancer

Prostate cancer is the most common cancer in men in Switzerland, with incidence increasing with age (median age at first diagnosis >70 years). In the localized stage, radical prostatectomy and radiotherapeutic procedures represent curative therapeutic approaches. In the active surveillance strategy, the patient is monitored closely and curative therapy is initiated only if the disease progresses. The main decision parameters for the choice of therapy in the localized stage are on the one hand the aggressiveness of the carcinoma [3] and on the other hand the state of health resp. The estimated life expectancy of the patient. For patients with good life expectancy, curative therapies can be offered analogous to younger patients [4]. For aggressive carcinomas, this may include radical prostatectomy and radiotherapy, and for low- and intermediate-risk carcinomas, active surveillance or watchful waiting. In the latter, palliative treatment is initiated only when tumor symptoms appear. Great progress has been made in recent years in both surgical techniques and radiation therapy (e.g., robot-assisted laparoscopic prostatectomy, optimized radiation fields, brachytherapy), which reduces morbidity risks. Patients in reduced health status, especially frail patients, usually do not benefit from curative therapeutic approaches and should be treated in a symptom-oriented manner.

In metastatic disease, as in younger patients, primary therapy consists of hormone deprivation achieved with LHRH agonists (or LHRH antagonists) or bilateral subcapsular orchiectomy. It should be noted that, especially in elderly patients, osteoporosis, metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease are favored. Calcium and vitamin D3 supplementation should be initiated for osteoprotection, and antiresorptive osteoporosis treatment should be initiated if osteoporosis is present. A recent study showed that patients with newly diagnosed disease may benefit from the early use of chemotherapy with docetaxel given in combination with hormone deprivation therapy. Especially in patients with extensive metastasis, a significant prolongation of survival was achieved, and the benefit was as great for older patients as for younger ones. In appropriate elderly patients, this option should be explored.

Disease progression despite hormone deprivation treatment is referred to as castration resistance. Treatment options for castration-resistant patients have improved significantly in recent years. Patient wishes, health status, and the side effect profile of each substance serve as guidelines for individualized treatment of elderly patients. Chemotherapy with docetaxel represents a long-standing standard of care, as this therapy has been shown to prolong survival as well as improve quality of life and pain control, with older patients benefiting as much as younger ones. Abiraterone (androgen synthesis inhibitor) and enzalutamide (androgen receptor inhibitor) are new anti-hormonal therapies that are effective both before and after chemotherapeutic treatment and are usually well tolerated. Another therapeutic option for patients with metastasis largely confined to bone is radionuclide treatment with radium 223. This therapy can improve pain, reduce skeletal complications, and improve prognosis even in elderly patients.

Breast Cancer

Breast cancer also shows an increase with age, so that a large proportion of women are at an older age when first diagnosed. In order to enable an optimal procedure in the local and locally advanced tumor situation, also for older patients, an interdisciplinary decision making with special consideration of the health status is inevitable. The treatment of older patients in good general condition is based on the procedure for younger patients. If the tumor situation permits, breast-conserving tumor surgery is the goal, since more extensive surgical procedures (mastectomy) are associated with increased functional limitations postoperatively in older patients [5]. Surgical axillary evaluation is sought only when it affects further therapeutic management.

Breast-conserving surgery is usually followed by adjuvant radiotherapy, which is also well tolerated by older patients. Whether this can be dispensed with under certain circumstances (e.g. patient >70 years with small, estrogen receptor-positive tumor) is ideally discussed on an interdisciplinary basis as well as with the patient. Further adjuvant therapy will depend on the risk situation and the biology of the tumor disease. For fit older patients, chemotherapies as well as HER2-targeted therapies may be considered in addition to endocrine therapy after a detailed evaluation of any comorbidities.

For older patients with health limitations, a good health status assessment is essential to evaluate whether or not the patient will benefit from tumor resection, which is associated with a lower risk of recurrence. If surgery is not an option, systemic therapy may be offered, such as endocrine therapy for a hormone receptor-positive tumor. For patients with severe health limitations (“frail”), a palliative symptom-based approach may be optimal.

In the metastatic setting, health status as well as patient wishes play a significant role in decision making in addition to tumor biology. The majority of carcinomas in elderly patients are hormone receptor-positive (and HER2-negative), making endocrine therapies, which are usually well tolerated, the first choice for palliative therapy. Aromatase inhibitors (e.g. letrozole or anastrozole) and the estrogen receptor antagonist fulvestrant are particularly worthy of consideration. Chemotherapies are available for patients with hormone receptor-negative carcinomas, and it has been shown that older patients can benefit from such treatments in a similar manner to younger patients [6]. Typically, better tolerated monotherapies are used rather than combination therapies. The choice of chemotherapeutic agent is strongly based on the patient’s organ function and preferences, with particular consideration given to cardiac or renal functional limitations. In HER2-positive disease, a HER2-targeted agent is usually added (e.g., trastuzumab).

Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC)

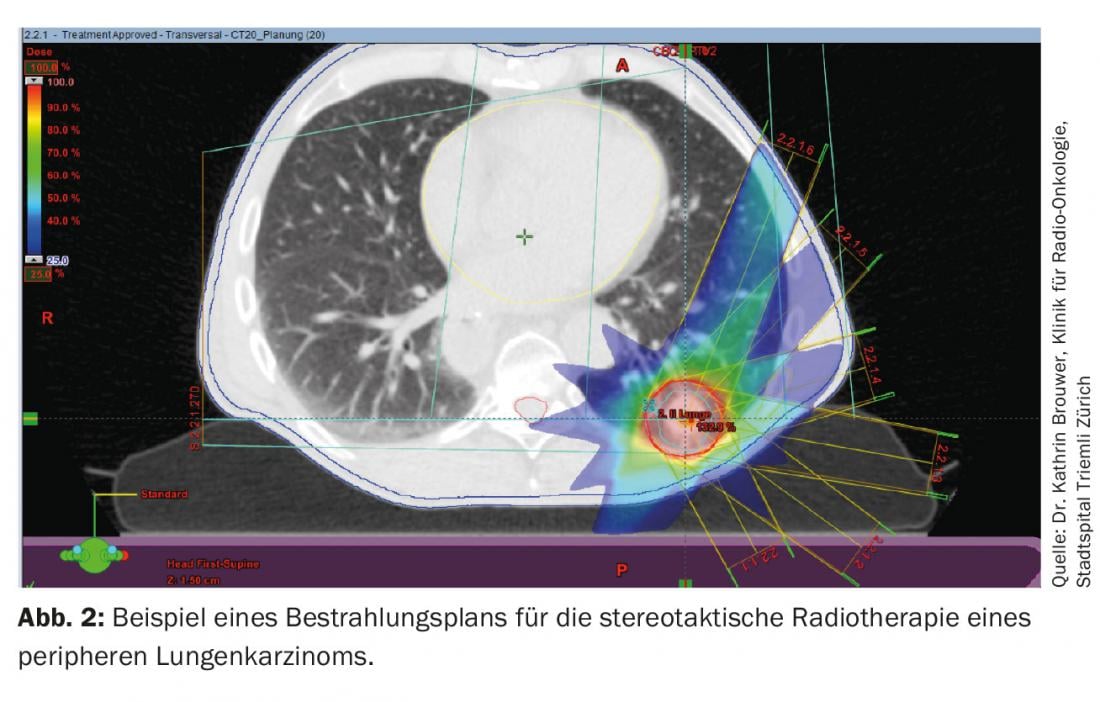

The median patient age at diagnosis of NSCLC is approximately 70 years. In the early stages, there is a possibility of cure, with surgical procedures being the standard. Whether chronologic age per se is a risk factor for increased postoperative morbidity and mortality is controversial. However, age older than 75 years, increased comorbidities, and treatment in hospitals with few appropriate patients appear to increase the risk of postoperative morbidity [7]. With the help of limited resections, e.g., omitting mediastinal lymphadenectomy, or with video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery, the risk of morbidity can be reduced to a very low level, so that such procedures may also be considered for patients of far advanced age. For patients who are not candidates for surgery, radiotherapeutic procedures are an alternative. In particular, stereotactic radiotherapy (SBRT) techniques that are precisely focused on the tumor can achieve very high local control rates while sparing the remaining lung tissue (Fig. 2) [8].

After resection, adjuvant chemotherapy (in stage II and IIIA) may reduce the risk of disease recurrence and improve survival. Adjuvant chemotherapies were also associated with a survival benefit in studies of older patients and were similarly well tolerated as by younger patients. However, the effect seems to exist only for patients under 80 years of age. Therefore, adjuvant treatment should be discussed for patients younger than 80 years of age in good general health.

In the metastatic setting, substantial progress has been made in recent years. For patients with tumors harboring an activating EGFR mutation or an ALK fusion oncogene, targeted therapies with high efficacy and good tolerability are available (gefitinib, erlotinib, afatinib, crizotinib). These treatments are therefore well suited to older patients, and appropriate investigations of tumor material should be arranged.

If targeted therapy is not an option, chemotherapies are available. Several studies show that chemotherapies are associated with benefit even in elderly patients. However, the adverse effects increase with the intensity of the therapy, so that the benefits and risks must be weighed together with the patient. While for fit patients, combination therapy of two agents may be considered (e.g., carboplatin and paclitaxel), monotherapies are otherwise preferred.

Colon Cancer

Colon cancers are among the most common cancers, with a clear incidence increase with age. The majority of patients today are already over 70 years old. In the localized stage, curative tumor surgery is the treatment of choice for older patients as well, although older patients have a less favorable prognosis than younger patients [9]. Increased early mortality in the first year after surgery appears to be a significant factor. Preoperative patient assessment plays a central role in identifying and adequately informing those patients who will benefit from the procedure and in providing a palliative approach for the others. Some patients also benefit from preoperative intervention. Thus, it has been shown that in patients with malnutrition, preoperative nutritional support for 7-10 days can reduce complications.

In locally advanced stages (specifically stage III), the benefit of adjuvant chemotherapy is well established, even for elderly patients. Monotherapy with a fluoropyrimidine (5-fluorouracil or capecitabine) is usually considered and is usually well tolerated. It should be noted that only sparse data exist for patients over 80 years of age, so that no statements can be made for this age group. The benefit of more intensive treatment (addition of oxaliplatin) is currently not well established for patients older than 70 years. Consideration of the patient’s health status and wishes are essential in decision making.

In the case of metastasis, a distinction is made as to whether the metastases are resectable or non-resectable. Metastatic surgery has been instrumental in the prognostic improvement observed in colorectal cancer in recent years, as much longer disease courses and, in a proportion of patients, cures can be achieved. Liver metastasectomy may also be of benefit to selected elderly patients [10]. However, the basis for this is an interdisciplinary assessment of the patient in a center with experienced experts.

Tumor-targeted therapies are available for non-resectable metastatic disease. These are aimed at prolonging survival and reducing tumor-related complications. In addition to providing the patient with detailed information, agreement on desired therapy goals is crucial to enable individually tailored treatment. In elderly patients, the focus is often on maintaining quality of life. Very fit and motivated older patients can be treated by analogy with younger patients. This includes combination chemotherapies and therapies with monoclonal antibodies.

The cornerstone of treatment for less fit patients is chemotherapy with a fluoropyrimidine. In the few studies conducted specifically with elderly patients, the addition of a second chemotherapeutic agent (oxaliplatin or irinotecan) or antibody therapy was tested (bevacizumab or cetuximab). While the addition of a second chemotherapeutic agent provided little or no additional benefit, the addition of antibody therapy appears to improve the efficacy of fluoropyrimidine with only modestly increased toxicities. The question of whether such treatment is appropriate in an elderly patient can only be clarified after oncological consultation in a joint discussion.

Bone metastases

Many patients with metastatic cancers (especially breast, prostate, and lung cancer) have bone metastases. These often lead to pain as well as further complications such as pathologic fractures, spinal canal compression, neurologic symptoms, or hypercalcemia. Bone metastases are a major cause of deterioration in quality of life. In addition to analgesic therapy, percutaneous radiotherapy in particular is available for pain relief; it often improves symptoms and is well tolerated. Instabilities or spinal canal compression often necessitate surgical intervention.

Osteoclast inhibitors (denosumab) and bisphosphonates (e.g., zoledronate) result in a significant reduction in skeletal events and can favorably affect pain symptomatology, making them a standard of care. When using these agents, the potential for osteonecrosis of the jaw or hypocalcemia must be considered and monitored. A check-up with the dentist before therapy and calcium substitution are recommended. In contrast to other tumor entities, in prostate cancer antiresorptive therapy should not be initiated from the beginning, but only at the castration-resistant stage (exception: osteoporosis treatment). If possible, tumor-targeted therapy should be initiated to prevent further progression of metastasis; in addition, effective tumor therapies can improve pain symptoms. Because of the major impact on quality of life, the above treatments should be evaluated and fully utilized, especially in elderly patients.

Literature:

- Wildiers H, et al: International Society of Geriatric Oncology Consensus on Geriatric Assessment in Older Patients With Cancer. J Clin Oncol 2014; 32: 2595-2603.

- Decoster L, et al: Screening tools for multidimensional health problems warranting a geriatric assessment in older cancer patients: an update on SIOG recommendations. Annals of Oncology 2015; 26: 288-300.

- D’Amico AV, et al: Biochemical outcome after radical prostatectomy, external beam radiation therapy, or interstitial radiation therapy for clinically localized prostate cancer. JAMA 1998; 280(11): 969-974.

- Droz JP, et al: Management of prostate cancer in older men: recommendations of a working group of the International Society of Geriatric Oncology. Lancet Oncol 2014; 15(9): e404-14. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70018-X.

- Sweeney C, et al: Functional Limitations in Elderly Female Cancer Survivors. J Natl Cancer Inst 2006; 98(8): 521-529.

- Schneider M, et al: Chemotherapy treatment and survival in older women with estrogen receptor-negative metastatic breast cancer: a population-based analysis. J Am Geriatr S 2011; 59(4): 637-646.

- Rueth NM, et al: Surgical treatment of lung cancer: predicting postoperative morbidity in the elderly population. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2012; 143: 1314-1323.

- Pallis AG, et al: Management of elderly patients with NSCLC; updated expert’s opinion paper: EORTC Elderly Task Force, Lung Cancer Group and International Society for Geriatric Oncolog. Annals of Oncology 2014; 25: 1270-1283.

- Papamichael D, et al: Treatment of colorectal cancer in older patients: International Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG) consensus recommendations 2013. Annals of Oncology 2015; 6(3): 463-476.

- Mazzoni G, et al: Surgical treatment of liver metastases from colorectal cancer in elderly patients. Int J Colorectal Dis 2007; 22: 77-83.

- Walter LC, Covinsky KE: Cancer Screening in Elderly Patients: A Framework for Individualized Decision Making. JAMA 2001; 285(21): 2750-2756. doi:10.1001/jama.285.21.2750.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2015; 3(7): 20-24.