The use of opioids is useful for certain nontumor-related pain conditions. Possible indications and contraindications should be considered. Therapy goals must be defined and monitored together with the patient. Established, stable therapy should also be reevaluated on a regular basis. Opioid therapy is generally carried out with sustained-release preparations. Fast-acting preparations should be used only in exceptional cases for dose-finding purposes. A dose of 120 mg/d oral morphine equivalent should be exceeded only in exceptional circumstances.

Globally, more opioids are prescribed every year [1]. This class of substances has a firm place in multimodal medicinal pain therapy and is used extremely successfully for certain acute and chronic pain conditions. However, there are many causes of pain for which the evidence for such therapy is marginal or entirely lacking. Nevertheless, the inhibition to use this class of substances seems to have fallen in recent years, especially for non-tumor-related pain. The reasons for this are manifold, as are the problems that arise as a result, as the example of the USA shows [2].

The goal of this article is to provide a brief overview of the appropriate use of opioids in practice based on current guidelines. The basis for the compilation comes, among others, from various current guidelines noted in the references, in particular the S3 LONTS guideline of the German Pain Society and the guideline of the US Center of Disease Control [3,4].

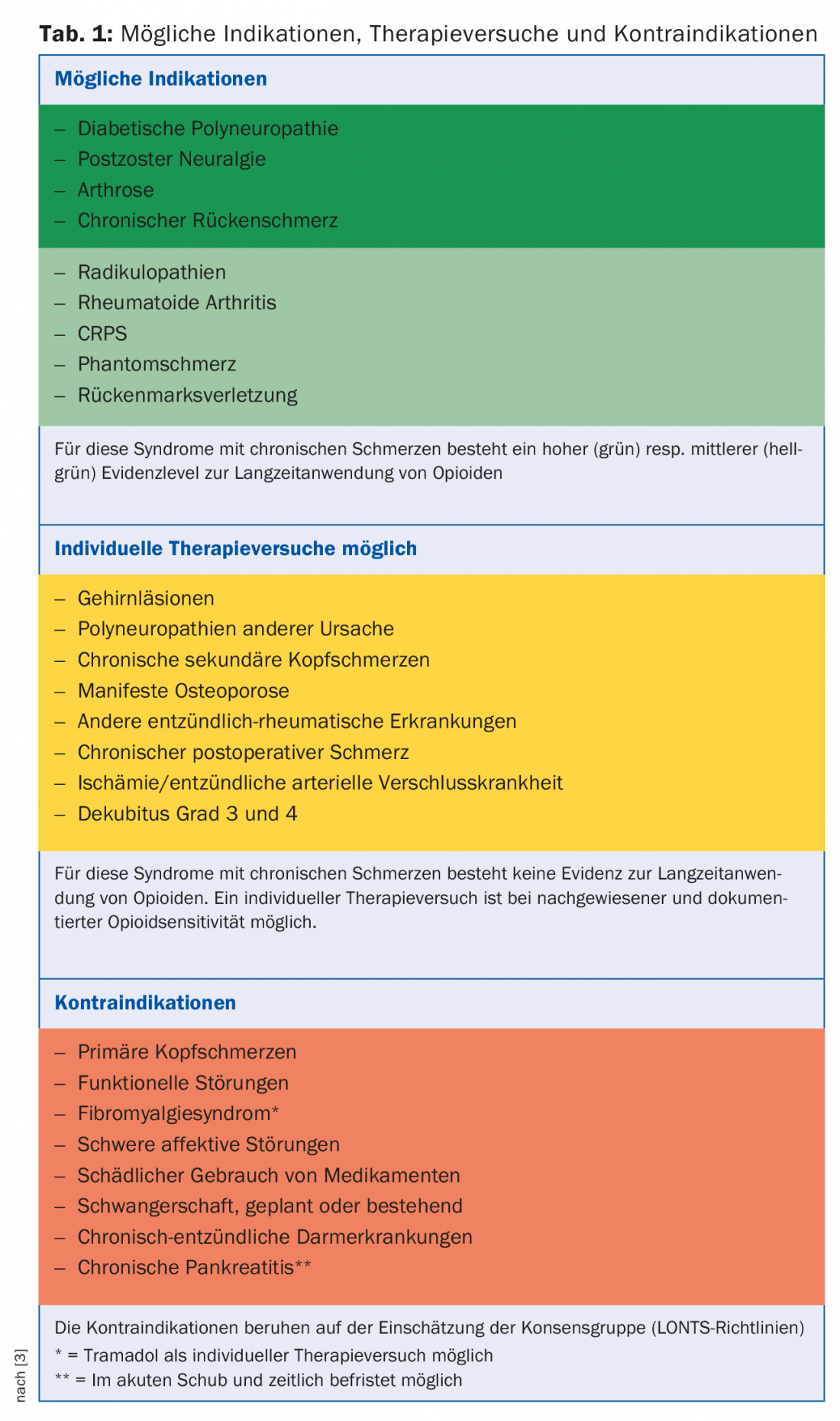

Indisputable is the use of both weak and strong opioids for tumor-related pain. There is a long clinical experience and also scientific evidence for this [5]. For all other non-tumor-related pain, the indication for long-term therapy must be strictly defined and repeatedly reviewed. However, high-quality studies demonstrating the effect even in non-tumor-related pain are limited to a relatively short time period (three months), due to the study designs chosen. Based on the pain mechanism, opioids are more appropriately used when there is an acute, time-limited, severe, nociceptive pain mechanism (such as in the perioperative setting). However, contrary to earlier views, there is now also good evidence that opioids can be used for neuropathic pain. However, it is also true here that there are hardly any studies that have lasted longer than three months and would thus allow generalization of the results to “long-term therapy” beyond this period. Opioids have no or only an insignificant effect on an inflammatory component. Table 1 provides an overview of the possible indications, treatment attempts and contraindications based on the LONTS guidelines [3]. These guidelines are based on the evidence in the literature on the one hand, and on the consensus of experts on the other.

Never first line option

Even if the indication is “correct” according to these recommendations, opioids are never the first choice. A therapy attempt with non-opioid medications or drugs should always be made first. a combination thereof can be performed. Only in exceptional cases should opioids be used outside this range of indications. However, this must then also be clearly declared as a “therapy trial” and be limited in time accordingly (e.g. three months). Prerequisites for such a trial are either failed or insufficient non-opioid drug-based pain therapies. Opioid sensitivity of pain must also be clearly documented (pain diary) and contraindications must be considered. Likewise, the success of this therapy should be reviewed and documented every three months.

Define therapy goal

Together with the patient, the individual therapy goal is clearly defined. Often, if not in the vast majority of cases, the realistic goal is not complete freedom from pain, but improvement of the pain situation by a certain factor (pain reduction >30%, improved functional capacity). This must be clearly communicated by the physician in the consultation before the start of therapy and it must be ensured that the patients understand it correctly and agree to it. This basis is the prerequisite for successful management and control of the therapy. The patient consultation also includes a detailed explanation of the common and potential side effects of this class of substances and their treatment. Likewise, the issue of driving ability must be addressed. The risk of such therapy, especially the potential for dependence, must not be downplayed under any circumstances. In Europe and Switzerland, there is never any talk of an “opioid epidemic”, as described in the USA due to various factors. However, it is a fact that also in this country more and more opioid-containing preparations are gaining approval [6] and in parallel more and more opioids are prescribed [1].

On the other hand, the fact that certain pain components may be opioid sensitive even in “soft” indications and therefore opioid therapy may be useful should not be neglected. When weighing the benefits against the risks of such therapy, we must not forget that non-opioid-based therapies also carry certain risks that can have equally dire consequences for patients (e.g., GI bleeding with NSAIDs).

Which opioid?

In recent years, we have seen a large increase in the number of approvals of opioid-based medications. In the last ten years alone, the number of preparations available to us doctors has multiplied. Many of these new formulations appear to have certain advantages in terms of efficacy and side effects. For example, mention should be made of combination preparations with the opioid antagonist naloxone, which leads to an improvement in intestinal motility through a local effect on the intestinal wall, or opioids with a dual spectrum of action, which also serve other mechanisms of pain signal generation. However, clinical experience shows a wide variance in response to different agents and also in the development of tolerance to individual compounds. Therefore, a differential indication of individual agents is difficult and there are still few reliable data that are groundbreaking in this respect.

Dosages

All opioid therapy is started with low dosages that are slowly increased (“start low, go slow”). Long-acting preparations are generally used for therapy at fixed times (“by the clock”) – depending on the duration of efficacy of the preparation. Short-acting preparations are used exclusively for titration of the dosage. They must never be used according to a fixed scheme. They carry a higher potential for dependence compared to long-acting forms and induce opioid tolerance more rapidly than the sustained-release preparations. As a result, a therapy can quickly get out of hand. Dosages should not exceed 120 mg p.o.-morphine equivalent. These dosages can be determined with the help of conversion tables for other active ingredients. A web-based electronic conversion table that is constantly updated according to the latest findings is provided, for example, by the Institute of Anesthesiology, University Hospital Zurich [7].

Therapy duration

Only if the pain is documented to be opioid sensitive (at least 30% pain reduction or significant improvement in functional ability, e.g., a significant increase in walking distance) is therapy longer than three months appropriate. Otherwise, the therapy should be discontinued and suspended. Long-term opioid therapy must always be monitored by the supervising physician. This includes checking for side effects such as loss of libido, psychological changes, fall events, or possible misuse of the medication.

In addition, patients must be advised that they are not fit to drive even during dosage changes.

Once a therapy is established, stably adjusted and the therapy goals are achieved, it should be re-evaluated again and again. If significant tolerance develops with an increase in need, rotation to another opioid may be considered. When converting to another active ingredient, however, the tolerance must be taken into account or included in the calculation. The dosages of the new preparation must be well below the calculated equipotency. Otherwise, there is a great risk of overdose and this can have unpleasant consequences for the patient.

Conflict of interest: PD Dr. Maurer has been supported by the following companies in the last five years: Boston Scientific AG, Solothurn, Switzerland; Bristol-Myers Squibb SA, Baar, Switzerland; Grünenthal Pharma Schweiz, Mitlödi, Switzerland; Janssen-Cilag AG, Baar, Switzerland; Medtronic, Bern, Switzerland; Mundipharma Medical Company, Basel, Switzerland; Pfizer AG, Zurich, Switzerland; St. Jude Medical AG, Zurich, Switzerland; Nevro Corp. CA 94025, USA. AstraZeneca, Zug, Switzerland.

Literature:

- International Narcotics Control Board: Narcotic Drugs – Technical Reports. New York 2016. www.incb.org/incb/en/narcotic-drugs/Technical_Reports/narcotic_drugs_reports.html

- Hauser W, et al: The opioid epidemic and the long-term opioid therapy for chronic noncancer pain revisited: a transatlantic perspective. Pain Manag 2016; 6(3): 249-263.

- Hauser W, et al: [Recommendations of the updated LONTS guidelines. Long-term opioid therapy for chronic noncancer pain]. Pain 2015; 29(1): 109-130.

- Dowell D, et al: CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain – United States, 2016. JAMA 2016; 315(15): 1624-1645.

- Caraceni A, et al: Use of opioid analgesics in the treatment of cancer pain: evidence-based recommendations from the EAPC. The Lancet Oncology 2012; 13(2): e58-e68.

- Swissmedic: directories. www.swissmedic.ch/bewilligungen/00155/00242/00243/00406/index.html?lang=de

- Institute of Anesthesiology: Opimeter. www.anaesthesie.usz.ch/fachwissen/Seiten/Opimeter.aspx

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2016; 11(7): 32-36