Once foolhardy, now standardized therapy: orthotopic liver transplantation gives many patients hope for a normal life.

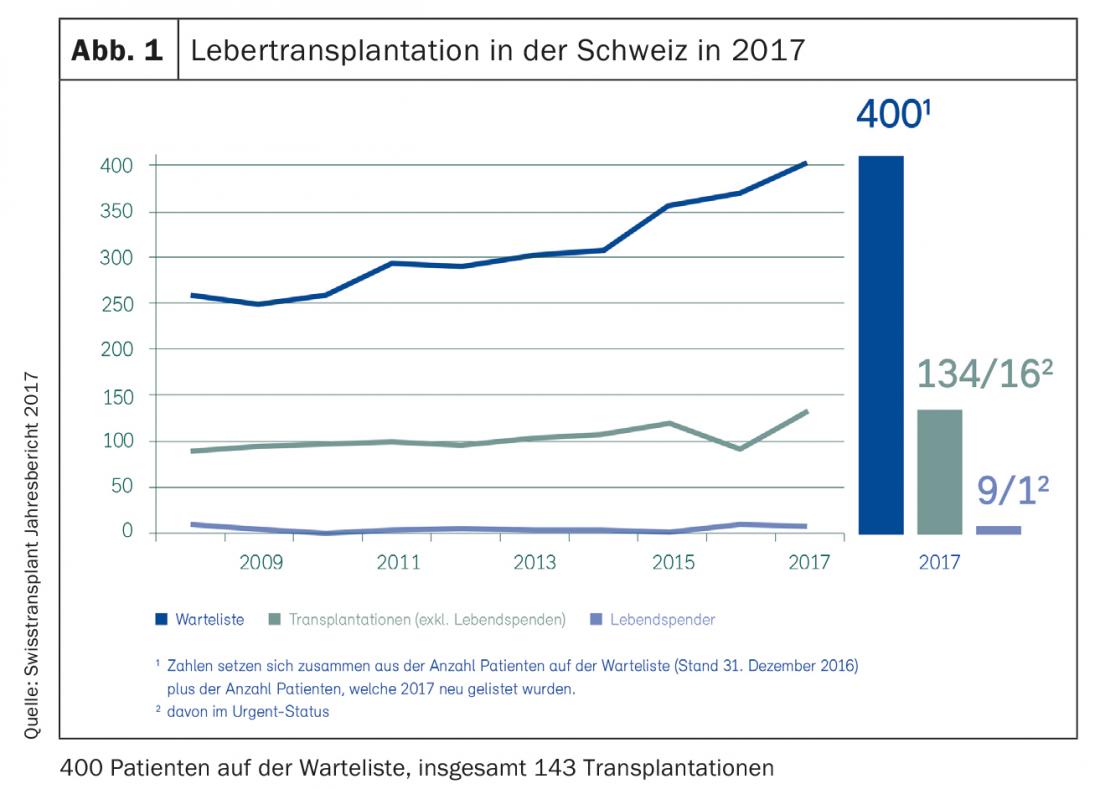

In Europe, more than 10,000 liver transplants are performed each year, and approximately 150 are performed in Switzerland (Fig. 1) [1]. The number of patients on the waiting list is steadily increasing, as is the number of those who die on the waiting list because a suitable donor organ did not become available in time. While orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT) required foolhardy surgeons and courageous patients 30 years ago, advances in surgical technique, perioperative management, and immunosuppressive therapy have made OLT a safe and highly standardized therapy. Significantly older, multimorbid recipients and donors have shaped and changed the risk profile in recent years. Nevertheless, OLT remains the only chance for many patients to return to a normal life.

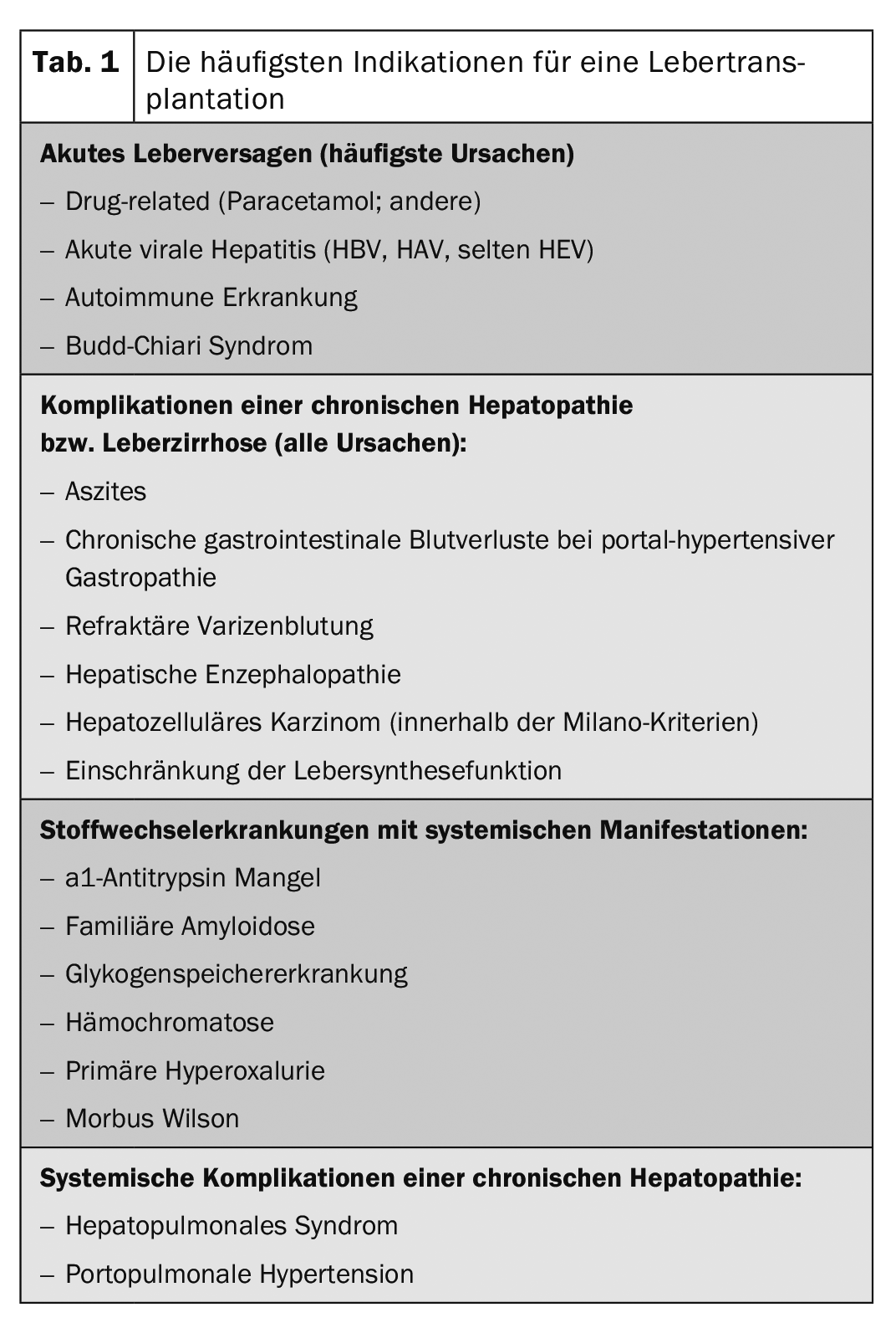

Indications for liver transplantation

The indications for OLT can be divided into acute liver failure, complications of chronic hepatopathy in the advanced stage of liver cirrhosis, and hepatic metabolic diseases with systemic manifestations (Tab. 1). The diagnosis of cirrhosis does not necessarily imply the need for OLT; rather, the indication must be made according to the clinical course, taking into account the complications and their treatability [2].

The allocation of donor organs in Switzerland is carried out centrally by Swisstransplant and is regulated by law. In Germany, Austria and Switzerland, the MELD score, which is composed of the International Normalized Ratio (INR), bilirubin and creatinine, is used for transplant allocation. In clinical practice, in addition to these parameters, there are numerous symptoms that lead to a significant reduction in quality of life (e.g., pruritus, therapy-refractory ascites) or are associated with increased mortality on the waiting list (especially hyponatremia in cirrhotic patients). After individual evaluation, this may justify requesting a special arrangement. Some indications are scored high regardless of the calculated MELD score, particularly hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and some systemic complications and metabolic diseases (e.g., hepatopulmonary syndrome, familial amyloid polyneuropathy).

In general, cirrhotic patients should be referred to a transplant center after the onset of initial decompensation (e.g., variceal hemorrhage, ascites, hepatic encephalopathy) because the prognosis of the disease worsens substantially at this point. With a steady decline in liver synthesis function, presentation should be made at the latest when a MELD score >10 is reached. Above a MELD of ≥15, the benefits of OLT outweigh the associated risks, so inclusion on the waiting list may be appropriate. The waiting time is highly variable depending on the clinical course, but generally a period of just under one year can be expected. In addition, in the case of acute liver failure with rapid deterioration of liver synthesis function, a highly urgent listing may be considered. If acute liver failure is suspected during the clinical course, contact should be made with a transplant center as early as possible. This should be distinguished from acute exacerbation of chronic hepatopathy, in which case a highly urgent listing is not possible.

In the case of a regular listing, the clarifications required in advance for active listing are organized and coordinated by the transplant coordination. In the outpatient setting, particular attention should be paid to infectious disease recommendations regarding vaccinations or therapies that should be performed prior to any transplantation.

Measures during the waiting phase

When caring for OLT-listed patients, care must be taken to perform sonographic HCC screening every six months. Bridging therapies that prevent progression in the interval before OLT must be mandatorily considered in the case of HCC [3]. Malnutrition and catabolic metabolism with loss of muscle tissue, including in obese patients (keyword “sarcopenic obesis”), should also be examined as part of clinical follow-up [4]. Early, aggressive intervention with optimization of nutritional status or improvement of muscular function can significantly improve outcome after OLT (keyword “prehabilitation”). What is needed here is a well-coordinated team of hepatologists and transplant surgeons, anesthesiologists and intensive care physicians, transplant coordinators, specialized nursing, nutritional counseling and physical therapists, as well as the family doctor, the family and, last but not least, the patient.

Any decompensations or deterioration of the general condition must suggest an infection and should be clarified in this regard. In case of deterioration of liver synthesis function as well as decompensation, prompt reporting to the transplant center in charge is essential.

This is particularly important since systemic infection or sepsis is an absolute contraindication for OLT, also in view of the subsequent immunosuppression required. Similarly, OLT is contraindicated in the presence of active extrahepatic or locally advanced or disseminated intrahepatic malignancy. In contrast, psychiatric comorbidities including alcohol abuse, provided that the patient has been abstinent from alcohol for at least six months, do not represent absolute contraindications and should be examined on an interdisciplinary basis in individual cases.

General surgical aspects

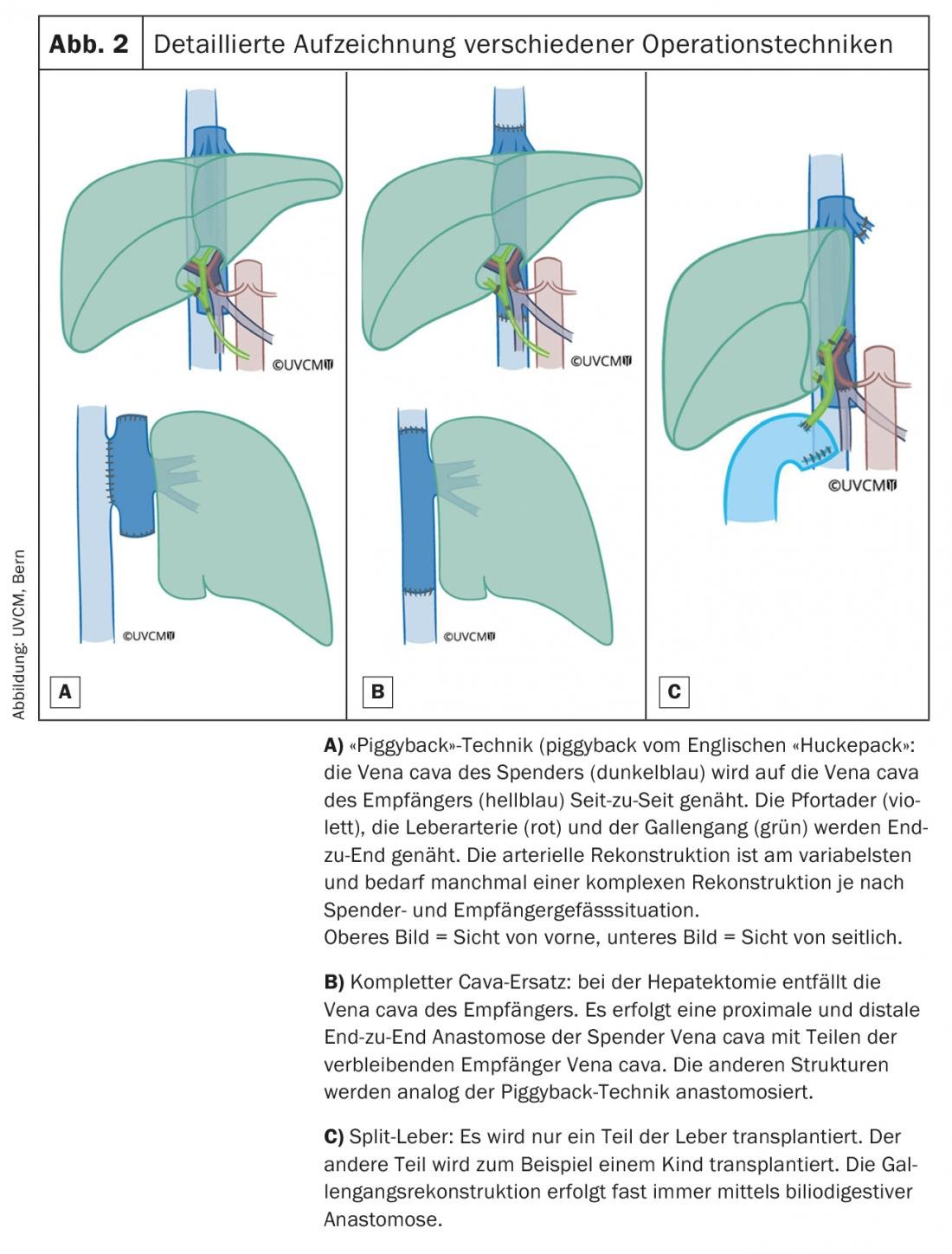

In recent years, not only survival after OLT has improved significantly (1-year survival at 83%, 5-year survival at 71%), but also time to complete recovery [5]. Significantly shorter operation times (4 h vs. previously >12 h) and improved perioperative management mean that extubation can often be performed very quickly with a correspondingly short stay in the intensive care unit. In 2018, the median postoperative length of stay in the ICU at Inselspital Bern <was 24 hours, and the median length of stay in the hospital was 8 days. With few exceptions, patients can usually return directly to their home environment. Figure 2 provides a detailed overview of which surgical techniques are used for the installation of the donor organ.

Donor liver type

In Switzerland, the vast majority of patients receive a liver from a deceased donor. This is usually a donor with primary brain damage or disease, with irreversible loss of function of the entire brain including the brain stem (so-called brain death; also known as “donation after brain death”, “DBD” donor). Another possibility is the removal of a liver from a donor with persistent circulatory arrest, which leads to death secondary to the lack of perfusion of the brain and brainstem. This is a so-called “DCD” donor, “donation after circulatory death”. In living liver donation, only part of the liver is removed. This is done mainly in countries where, due to legal, religious and cultural requirements, cadaveric donation is rejected.

Living liver donation is also very well suited for pediatric transplant programs, as children would otherwise have to wait a very long time for a suitable donor organ. Throughout Switzerland, living liver donation is rarely performed. One way to expand the donor pool is the use of marginal donor organs (“extended criteria donor”), i.e. transplantation of older organs (>65-70-yr-old), organs with a higher degree of steatosis or formerly hepatitis-C positive donors, etc. DCD livers also fall into this category. Efforts are underway worldwide to reduce the risk in these situations with the use of various perfusion machines, mostly ex situ. There are hypothermia-based protocols (+/- oxygen addition) according to which the liver is preconditioned to prevent postoperative complications such as ischemic cholangiopathy. Other groups use normothermic machine perfusion to better assess organ function pre-implantation. Initial reports are promising, but it remains to be seen which protocols will ultimately prevail and whether both methods (in all their variations) are equivalent [6].

Early postoperative complications

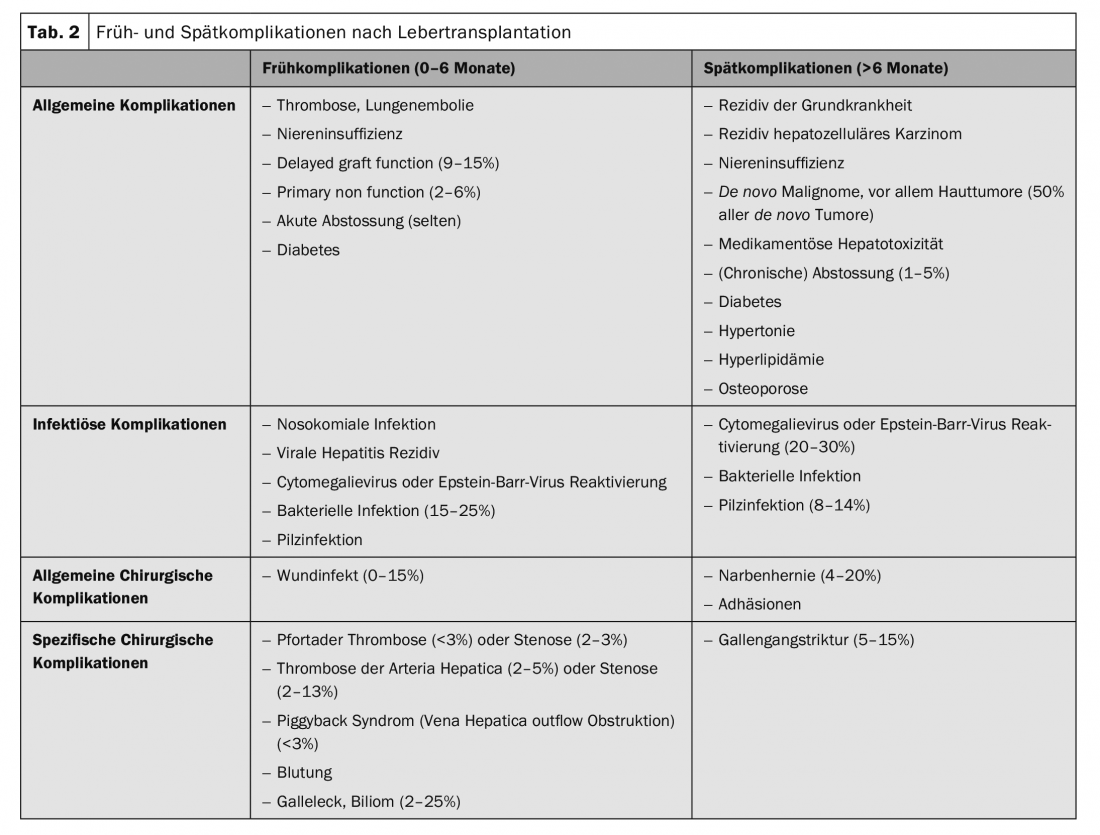

Although OLT has become significantly safer in recent years, potential obstacles still need to be overcome. Table 2 provides an overview of the most common early complications after OLT [7–9]. Overall, postoperative morbidity is up to 78% with a 30-day mortality of 5.7% [7]. Furthermore, bile duct problems and infections remain the Achilles’ heel of OLT. The latter can be significantly reduced by the lowest possible dose of immunosuppressants and adequate vaccination. Bile duct strictures can be treated endoscopically in the vast majority of cases, by means of papillotomy, dilatation, and stent placement. However, in the absence of response, surgical revision with placement of a hepaticojejunostomy often remains the only definitive solution in the course. Difficult is the therapy of diffuse intrahepatic bile duct problems. A phenomenon that can occur more frequently in DCD transplants (ischemic diffuse cholangiopathy). In some circumstances, retransplantation is the only reasonable therapeutic option in this situation.

Especially for freshly transplanted patients, it is essential to contact the transplant center early on if complications are suspected, to discuss the further procedure.

Long-term follow-up

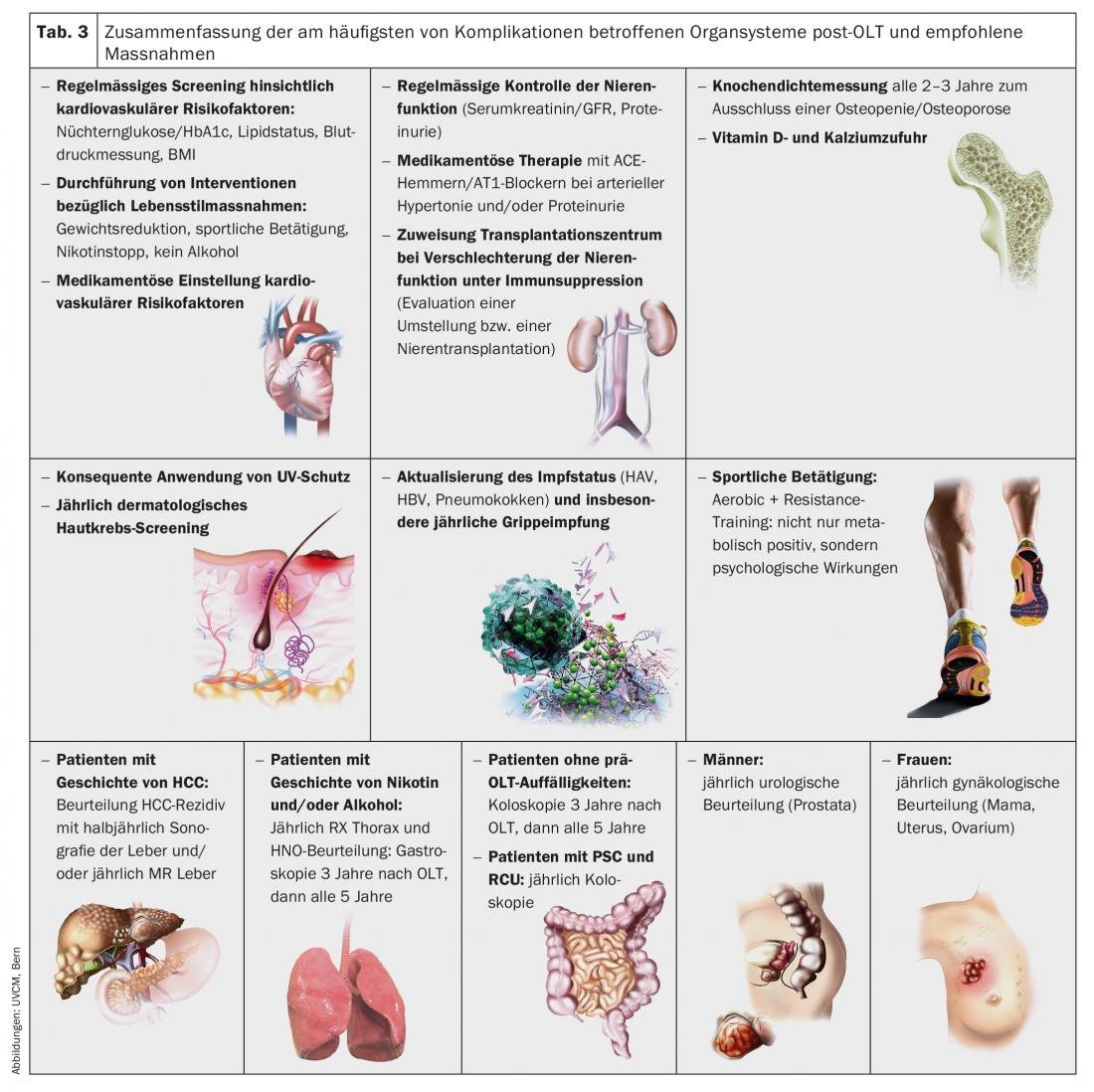

Long-term complications, which can occur in the period of months to years after OLT, must be considered in the care of transplanted patients because they significantly affect the long-term prognosis. The major organ systems affected and recommended actions are summarized in Table 3 [10].

Consistent prevention and strict adjustment of cardiovascular risk factors has relevant impact on long-term survival after OLT. In particular, the presence of diabetes mellitus and arterial hypertension should be regularly checked and treated at a low level by means of lifestyle measures or medication. In the presence of risk factors such as obesity or nicotine abuse, counseling on lifestyle adjustment is indicated, if necessary by means of specific dietary or smoking cessation counseling.

Therapy goal: Increase in quality of life

OLT can nowadays be considered as a highly specialized “routine procedure” with low perioperative mortality and, if properly indicated, very good long-term outcome. The ultimate goal is not only to relieve the patient of his chronic disease in the short term, but also to enable a good quality of life without significant restrictions in everyday life in the long term. However, in cases of persistent organ deficiency, it is hoped that in the future other therapies, such as cellular therapy with stem cells or the use of “bioartificial” livers, will replace the need for “classical” OLT.

Take-Home Messages

- Cirrhotic patients should be referred to a transplant center after the onset of initial decompensation, or at the latest when a MELD score >10 is reached.

- “Prehabilitation” with early, aggressive optimization of nutritional status and muscular function critically improves outcome after OLT.

- Advances in surgery, anesthesia, and perioperative management of patients after OLT have led to a significant reduction in risk, with usually rapid recovery and short hospitalization time.

- Bile duct problems and infections are the most important postoperative complications and prompt referral to the transplant center is strongly indicated.

- Strict adjustment of cardiovascular risk factors should be undertaken, as this significantly affects long-term survival after OLT.

Literature:

- Swisstransplant. Annual Report 2017. www.swisstransplant.org/fileadmin/user_upload/Swisstransplant/Jahresbericht/SWT_Geschaeftsbericht_A4_2017_de_def_web.pdf, accessed on 17.12.2018

- Martin P, et al: Evaluation for liver transplantation in adults: 2013 practice guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the American Society of Transplantation. Hepatology 2014; 59(3): 1144-1165

- European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Journal of hepatology 2018; 69(1): 182-236.

- European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on nutrition in chronic liver disease. Journal of hepatology 2019; 70(1): 172-193.

- European Liver Transplant Registry, recipient Data. www.eltr.org, last accessed 03 Jan. 2019.

- Jia JJ, et al: Machine perfusion for liver transplantation: A concise review of clinical trials. Hepatobiliary & pancreatic diseases international. HBPD INT 2018; 17(5): 387-391.

- Agopian V, et al: The evolution of liver transplantation during 3 decades: analysis of 5347 consecutive liver transplants at a single center. Ann Surg 2013; 258(3): 409-421.

- Kochhar G, et al: World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19(19): 2841-2846.

- Piardi T, et al: World J Hepatol 2016; 8(1): 36-57.

- Lucey MR, et al: Long-term management of the successful adult liver transplant: 2012 practice guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the American Society of Transplantation. Liver transplantation 2013; 19(1): 3-26.

CARDIOVASC 2019; 18(1): 20-25