At the German Pain Congress in Hamburg, experts provided insights into the current options for pain therapy. This is not infrequently characterized by patients having to weigh up (especially gastrointestinal) side effects against effective pain relief. In minor surgical procedures, analgesic measures are often too lax and the patient’s pain is underestimated.

(ag) Prof. Gertrud Haeseler, MD, Dorsten, Germany, showed how patients can benefit from analgesics postoperatively: Studies show that pain is one of the most important, if not the most important, symptom that patients want to avoid after surgery [1]. Physicians should actually take this fact into account in their surgical and postoperative planning. Nevertheless, today’s acute postoperative pain management cannot yet be described as satisfactory, although the necessary resources and knowledge from high-quality guidelines are actually available. This is partly due to lack of organization and partly due to underuse of opioids. According to surveys, traumatologic and orthopedic procedures are among the most painful surgeries [2]. After orthopedic surgery, tapentadol “immediate release” (IR) doses of 50 and 75 mg have been shown to be equally effective against moderate to severe pain as oxycodone HCl IR 10 mg (with better gastrointestinal tolerability) [3]. The reduction of opioid-typical side effects such as nausea, vomiting, and constipation was also confirmed by a meta-analysis [4].

Do minor interventions also mean less pain?

Prof. Dr. med. Esther M. Pogatzki-Zahn, Münster, Germany, discussed postoperative analgesia after minor surgery: “Pain scores after so-called minor surgery are higher than after many major surgeries. Logical would actually be: smaller surgery = less tissue trauma and therefore less pain. What is forgotten, however, is that in these situations significantly fewer painkillers are administered (due to a frequent underestimation of pain). This ultimately results in greater pain for the patient than after major surgery, where he or she receives optimal care (i.e., regional analgesic and acute pain service).”

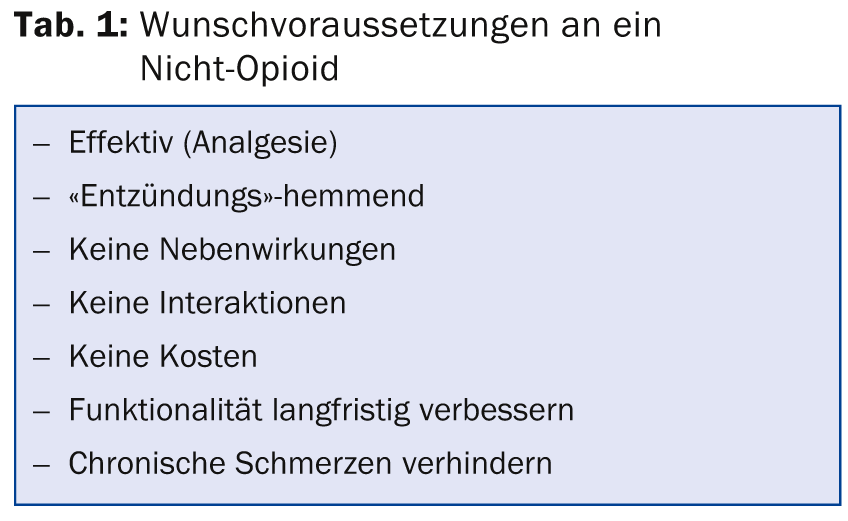

Non-opioid analgesics are initially used for postoperative pain management (Table 1).

This should be treated early and long enough, because severe pain is a major risk factor for chronicity. Pain therapy that influences sensitization processes (e.g., through PGE2) is therefore likely to be particularly effective in chronification prophylaxis. Etoricoxib has been shown to have PGE2 inhibitory effects [5]. COX inhibition has both analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects and prevents chronicity. Risks associated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug therapies include gastrointestinal complications (probability increases with age, dose, and duration of therapy), perioperative bleeding, acute renal failure (even with short-term use), cardiovascular complications, and wound healing disorders. Here, the various non-opioid analgesics differ: COX-2 inhibitors and diclofenac, for example, are contraindicated in existing heart failure (NYHA II-IV), ischemic heart disease, peripheral artery disease, or cerebrovascular disease. Paracetamol is contraindicated in hepatic dysfunction; metamizole should not be used in disorders of bone marrow function or diseases of the hematopoietic system, as well as circulatory instability.

Chronic back pain with neuropathic component

Among chronic pain conditions, back pain is very common, and in many severe cases a neuropathic component cannot be ruled out, which complicates treatment. Prof. Ralf Baron, MD, Kiel, Germany, sees tapentadol retard as a potential first-line option for the treatment of opioid-requiring back pain with a neuropathic pain component. At the congress, he presented an as yet unpublished IIIb/IV study [6] comparing this agent with the fixed combination oxycodone/naloxone retard. The 258 opioid-naive patients with confirmed neuropathic pain component (painDETECT questionnaire) were randomized to 2× 50 mg/d tapentadol retard (n=130) or 2× 10 mg/5 mg/d oxycodone/naloxone retard (n=128). A three-week titration phase (maximum 2× 250 mg/d tapentadol retard or 2× 40 mg/20 mg/d oxycodone/naloxone retard + 2× 10 mg/d oxycodone retard) was followed by a nine-week maintenance phase at the individually optimal dose.

Results: The primary endpoints were self-rated pain intensity during the last three days on an 11-point scale (NRS) and self-rated change in constipation symptom severity over the course of treatment (PACSYM questionnaire) [7]. This is of interest because many patients discontinue opioid analgesic therapy due to gastrointestinal problems. Tapentadol proved non-inferior in the efficacy endpoint (in fact, it achieved a 37 percent greater reduction in pain, p=0.003). Non-inferiority was also found in the tolerability endpoint. The incidence for constipation was 40% lower under tapentadol (p=0.045). In addition, significant improvements occurred in specific neuropathic pain symptoms, health-related quality of life, and functionality.

Implications for the family physician

In family practice, severe chronic back pain is a common condition, according to Stefan Regner, MD, of Mainz, Germany. Although in many cases a neuropathic component can be assumed, in the practice of the primary care provider there is often not enough time for a more in-depth diagnosis of the pain components. Particularly in the case of severe back pain, one repeatedly comes up against therapeutic limits and has soon exhausted the options – not least because of the limiting gastrointestinal side effects. The treatment is long, difficult and not infrequently frustrating. According to the speaker, new therapy options with a better side effect profile are therefore urgently needed, especially for compliance and patient satisfaction. “We can only do something about the pain if the patient actually takes the medication,” he says. In addition, for primary care physicians, the time required to treat chronic back pain is reduced. In the German S3 guideline “Long-term use of opioids for non-tumor-related pain”, which was updated in September 2014, the authors positively emphasize the good tolerability and efficacy of Tapentadol retard based on the current data.

Source: Lunch Symposium and Meet the Expert at the German Pain Congress, October 22-25, 2014, Hamburg.

Literature:

- Jenkins K, et al: Br J Anaesth 2001 Feb; 86(2): 272-274.

- Meissner W, et al: Dtsch Arztebl Int Dec 2008; 105(50): 865-870.

- Daniels S, et al: Curr Med Res Opin 2009 Jun; 25(6): 1551-1561.

- Merker M, et al: Pain 2012 Feb; 26(1): 16-26.

- Renner B, et al: Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 2010 Feb; 381(2): 127-136.

- Baron R, et al: Effectiveness of tapentadol prolonged release (PR) versus oxycodone/naloxone PR for severe chronic low back pain with a neuropathic pain component. Poster presented at PAINWeek September 2014, Las Vegas, USA.

- Binder A, et al: Safety and tolerability of tapentadol prolonged release (PR) versus oxycodone/naloxone PR for severe chronic low back pain with a neuropathic pain component. Poster presented at PAINWeek September 2014, Las Vegas, USA.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2015; 10(1): 24-26