The incidence of chlamydial and gonococcal disease in Switzerland is increasing. At the same time, multidrug-resistant gonococci and M. genitalium complicate antibiotic therapy. New strategies are needed to prevent the spread of these pathogens.

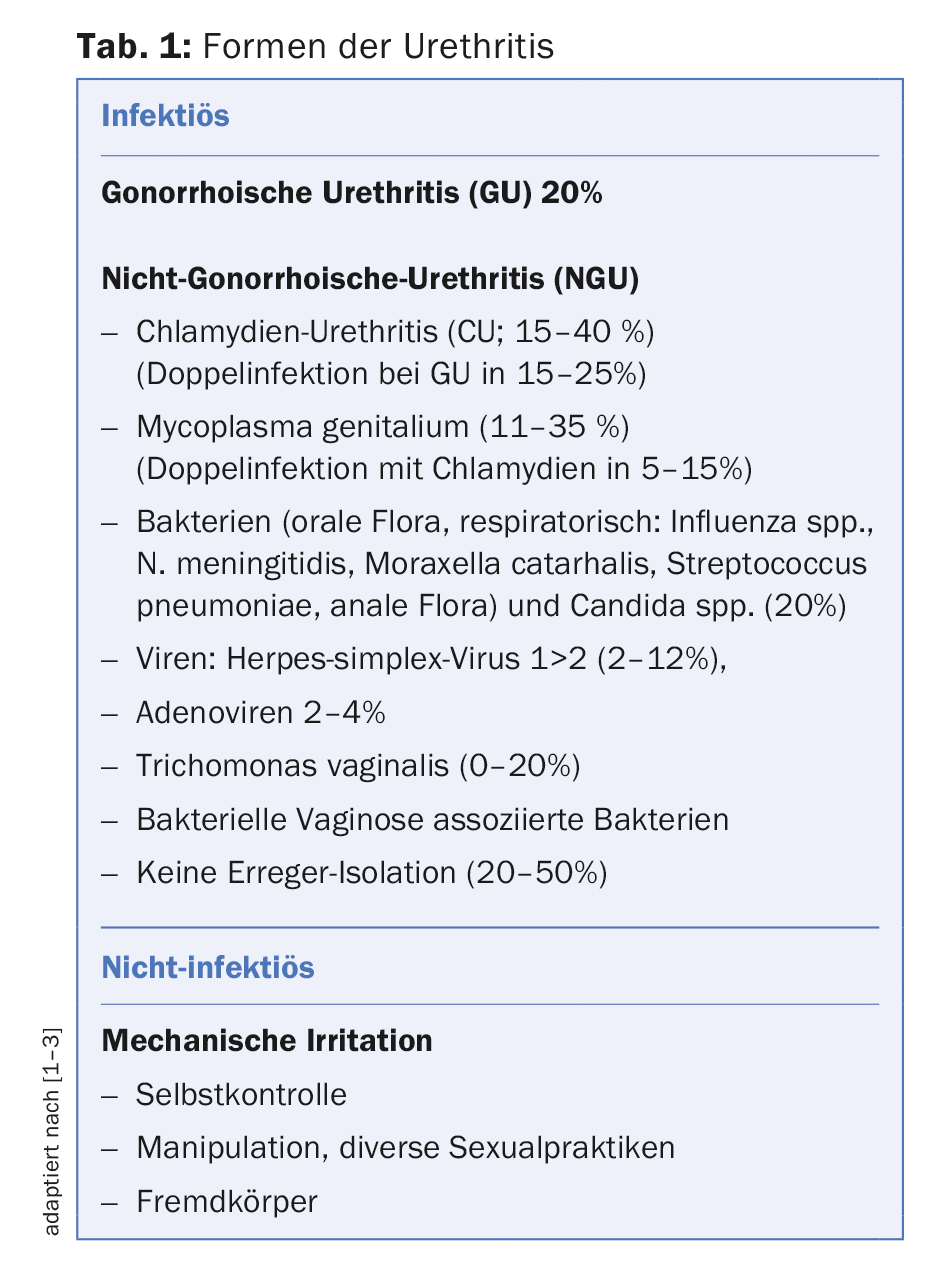

Urethritis is the most common sexually transmitted disease in men. It represents inflammation of the urethra with proliferation of leukocytes in the urethral exudate. While infectious and noninfectious causes may be present (Table 1), it is most commonly due to sexually transmitted pathogens. Because of the high incidence and potential complications of urethritis pathogen infection in patients and sexual partners, management of the disease is a high priority in public health care. The goals of treatment, in addition to symptom management, are to avoid complications and to reduce the transmission of co-infections (such as HIV). The identification and treatment of contact persons as well as educational measures with motivation for adapted behavior ultimately have additional epidemiological significance.

Classification and symptoms

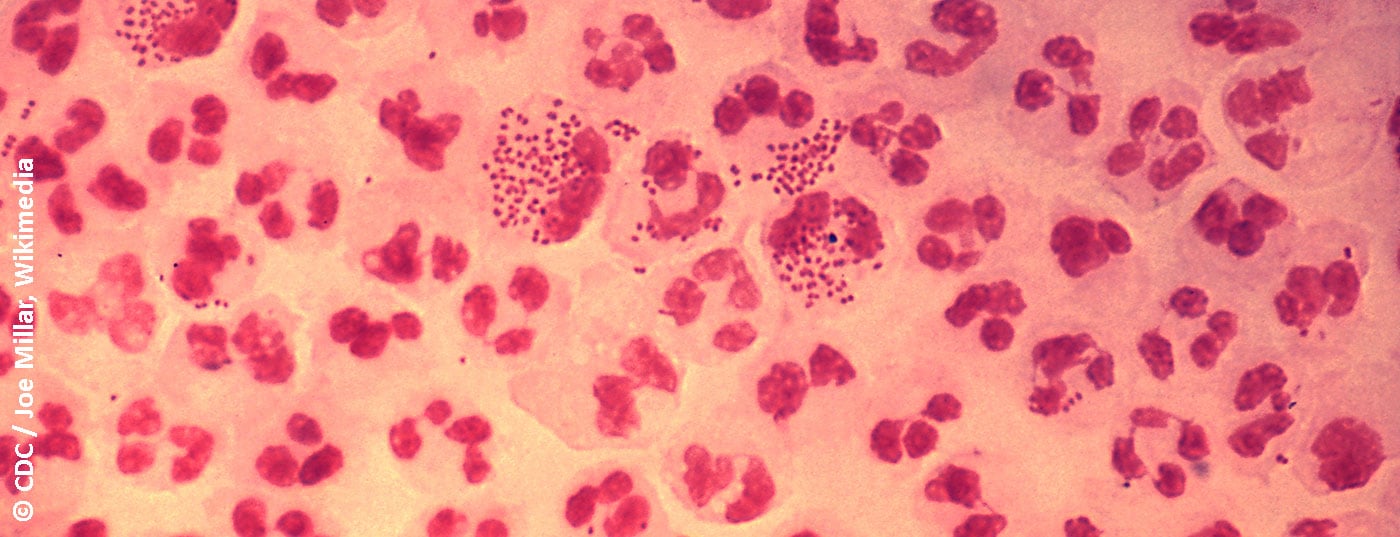

The classification of urethritis into gonorrheic and non-gonorrheic forms is based on traditional Gram staining of urethral discharge for gram-negative diplococci. Typical symptoms are discharge, typically purulent in gonorrheic urethritis (Fig. 1), mucoid in non-gonorrheic urethritis. Other possible symptoms include dysuria, urethral burning or itching, and irritation of the meatus urethrae, sometimes with accompanying balanitis. However, urethritis is also often asymptomatic [4]. Urethritis must be distinguished from a urinary tract infection or prostatitis, which should be considered as a differential diagnosis.

Pathogen spectrum

The most common pathogens are Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis, and mycoplasma, especially Mycoplasma genitalium (M. genitalium). The incidence of chlamydial infections as well as gonorrhea have increased sharply in Switzerland in recent years. Among mycoplasmas, the pathogenic significance of M. genitalium is best established. It should be noted that the difficulty of complete eradication and an increasing resistance problem complicate mycoplasma therapy. Currently, the authors of the UK guidelines for the management of M. genitalium infections have argued against screening asymptomatic individuals as this is more likely to cause harm at a population level [5]. So far, too little attention has been paid to the importance of pathogens of bacterial vaginosis as a cause of urethritis. After oral intercourse, respiratory germs such as Haemophilus spp. and viral pathogens such as herpes simplex and adenoviruses (here often with accompanying conjunctivitis) occur more frequently. In travelers returning from endemic areas, a search for Trichomonas vaginalis may also be useful.

Diagnostics

The workup of urethritic symptoms includes history, clinical examination, preparation of a direct specimen supplemented by laboratory testing for urethritic pathogens. In addition, expanded screening for sexually transmitted diseases such as HIV and syphilis is usually appropriate. The sexual history (in the patient’s own language) should explore sexual practices, protective measures, number of partners, and sexual orientation in order to make a differentiated risk assessment and provide targeted counseling to the patient. Clinically, in addition to an assessment of the fluorine, an inguinal lymphadenopathy is sought as well as any ulcerations. Diagnosis includes, whenever possible, a direct preparation, in the male by means of a smear from the urethra, in the female prepared from the cervical canal [6].

The morphology of the smear helps in differentiating gonorrheic urethritis from non-gonorrheic urethritis on the basis of typical intracellular diplococci, as well as from a viral genesis with predominance of mononuclear cells. Sensitivity and specificity of other diagnostic methods are inferior to urethral swab. If microscopy is not available, urethritis can be diagnosed based on the presence of mucopurulent discharge, a positive leukocyte esterase test in the first-stream urine examination, or the presence of streaks in the first-stream urine (also possible physiologically) [6].

Urethral swabs or initial stream urine are additionally tested by gene amplification for Neisseria gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis and, in symptomatic patients, also for M. genitalium. A bacteriological examination of the smear by means of culture should always be attempted, since the culture is used to examine the resistance profile of the gonococci and thus to search for further bacterial pathogens. If available, macrolide resistance should also be sought when M. genitalium is identified, using polymerase chain reaction (“PCR”) to analyze known resistance genes. In female patients, examination of the vaginal swab for gene amplification is superior to first-stream urine in the diagnosis of gonorrhea or chlamydial infection.

Therapy

In patients with confirmed urethritis, concurrent treatment of both gonococci and chlamydia is recommended unless gene amplification test results are already available to limit therapy to the specific pathogen. Treatment recommendations for gonorrheic and non-gonorrheic urethritis without complications, adapted from current guidelines, are summarized in Table 2. For gonorrhea, the standard is dual antimicrobial combination therapy. The combined therapeutic approach is expected to provide better assurance of eradication, potentially preventing the spread of resistant gonococci. In non-gonorrheic urethritis, therapy with doxycycline is directed at chlamydial infection; there is no known resistance problem here. If an infection with M. genitalium is present, however, only 30% are treated with doxycycline, and the therapy does not result in the development of resistance [7].

Therapy with azithromycin 1 g (single dose) should be avoided if possible because of the risk of using it to induce macrolide resistance in M. genitalium. Azithromycin is not a reliable therapy, especially for common asymptomatic rectal chlamydial coinfection. If M. genitalium is detected, azithromycin should be administered over several days, e.g., 500 mg on day 1 followed by 250 mg daily for an additional 4 days. This achieves better eradication than single dose [7], resulting in less resistance [8]. Potential hepatotoxicity must be considered when using moxifloxacin.

Identification and therapy of sexual partners is obviously of high importance for the affected partner, for the patient to prevent reinfection and epidemiologically especially in view of the increasing resistance problem. As a guideline, sexual partners of the last 60 days should be clarified and treated. The recommendation for sexual abstinence is for at least one week or until the investigation is completed [1].

In the case of gonococci, the success of the therapy is checked after two weeks at the earliest [9], and in the case of mycoplasmas after three weeks at the earliest, or better after five weeks [7]. Treatment monitoring for chlamydia is recommended only during pregnancy or after second-line therapy four weeks after therapy [10]. However, reinfection with chlamydia should be sought after three months.

Measures to curb the development of resistance in gonococci and M. genitalium.

In gonococci and M. genitalium, cases of extensive resistance to commonly used antibiotics are being detected worldwide, and their spread is feared. In recent years, a decrease in the susceptibility of gonococci to ceftriaxone has been observed in Switzerland [13]. In 2018, a total of three cases of gonococcal infections resistant to both ceftriaxone and azithromycin have been identified in England and Australia [14]. In M. genitalium, macrolide resistance is common in countries where first-line azithromycin therapy is used. On moxifloxacin, resistance is present in <10% in Europe, and is much more common in Asia. Due to the resistance situation, fears are being voiced that infections with M. genitalium will soon no longer be treatable.

Measures to combat resistance in gonococci include consistent removal of a culture and, in the case of M. genitalium, the search for resistance genes by gene amplification if possible in order to use a therapy adapted to the resistance determination. Depending on the pathogen, the often asymptomatic concomitant pharyngeal and anal infections must also be taken into account, which should be increasingly sought and treated. The use of azithromycin 1 g single dose should be avoided if possible, and even its use in combination therapy of gonorrhea is controversial. The implementation of a therapy control, partner therapy and preventive measures regarding sexual behavior are further measures to prevent the spread of resistant pathogens.

Take-Home Messages

- The incidence of chlamydial and gonococcal disease in Switzerland is increasing.

- At the same time, worldwide, including in the European region, in the

- In recent years, multidrug-resistant gonococci and M. genitalium have been found that can no longer be treated with commonly used antibiotics.

- New strategies are indicated to prevent the spread of these pathogens.

Literature:

- Lautenschlager S: Non-gonorrheal urethritis: pathogen spectrum and management. Journal of Urology and Urogynecology 2014; 21 (1) (issue for Switzerland): 17-20.

- Moi H, Blee K, Horner PJ: Management of non-gonococcal urethritis. BMC Infect Dis 2015;15: 294.

- Bachmann LH, et al: Advances in the Understanding and Treatment of Male Urethritis. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 61(Suppl 8): 763-769.

- Kälin U, Lauper U, Lautenschlager S: Urethritis. Pathogen spectrum, clarification and therapy – Part 2. Schweiz Med Forum 2009; 9: 121-124.

- Soni S, et al: 2018 BASHH UK national guideline for the management of infection with Mycoplasma genitalium, draft, download from www.bashhguidelines.org/media/1182/bashh-mgen-guideline-2018_draft-for-consultation.pdf, last accessed 16 Nov 2018.

- Horner P, et al: 2016 European guideline on the management of non-gonococcal urethritis. International Journal of STD & AIDS 2016; 27: 928-937.

- Jensen JS, Cusini M, Gomberg M, Moi H: 2016 European guideline on Mycoplasma genitalium infections. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2016; 30: 1650-1656.

- Lau A, et al: The Efficacy of Azithromycin for the Treatment of Genital Mycoplasma genitalium: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 61: 1389-1399.

- Bignell C, Unemo M: 2012 European guideline on the diagnosis and treatment of gonorrhoea in adults. Int J STD AIDS 2013; 24: 85-92.

- Lanjouw E, et al: 2015 European guideline on the management of Chlamydia trachomatis infections. Int J STD AIDS 2016; 27: 333-348.

- Toutos Trellu L, et al: Gonorrhea: new recommendations on diagnosis and treatment. Switzerland Med Forum 2014; 14(20): 407-409.

- Horner P, et al: 2016 European guideline on the management of non-gonococcal urethritis. International Journal of STD & AIDS 2016; 27(11): 928-937.

- Kovari H, et al: Decreased susceptibility of Neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates from Switzerland to cefixime and ceftriaxone: antimicrobial susceptibility data from 1990 and 2000 to 2012. BMC Infectious Diseases 2013; 13: 603.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control: Rapid Risk Assessment: Extensively drug-resistant (XDR) Neisseria gonorrhoeae in the United Kingdom and Australia, Date of publication 7 May 2018, www.ecdc.europa.eu, last accessed 07 Nov 2018.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2018; 28(6): 4-7