Damage to peripheral nerves caused by sports often remains undetected for a long time, because the neurologist is usually not routinely consulted for sports injuries. As training volumes increase, overuse-related nerve damage plays an increasingly important role. In addition to competitive athletes, ambitious amateur athletes in particular represent a risk group, as they often have poorer technique when practicing their sport and the training volumes are often increased too quickly. Treatment is primarily conservative with specific physiotherapy, technique training and, if necessary, medication with the administration of anti-inflammatory drugs.

In principle, all nerves can be injured during sporting activity, although certain types of nerve damage are particularly common in individual sports. These include, above all, compression- and overload-related nerve damage as well as direct injuries to nerves in the context of sports accidents that are accompanied by fractures or extensive wounds. Damage to peripheral nerves is often not detected or is detected too late, especially since the neurologist is usually not routinely consulted for sports injuries. Depending on the etiology, treatment is usually primarily conservative with specific physiotherapy, technique training, and, in the case of overuse-related injuries, modifications of the movement sequences or modifications of the sports equipment. Recently, extracorporeal sound wave treatment has also been used. Medication often requires the administration of anti-inflammatory drugs; only rarely are local injections with local anesthetics or glucocorticoids indicated. Except for acute mechanical nerve injury, surgical procedures are considered only when conservative methods fail.

The exact incidence of sports-related peripheral nerve injuries is currently unknown due to a lack of studies. Data vary between 0.5 and 6% of sports-related injuries; far more common are injuries to the musculoskeletal system. However, there is likely a bias in the studies to date because a large number of patients with sports injuries do not currently receive neurologic evaluation. It may well be that delays in rehabilitation of sports injuries are at least partly due to peripheral nerve injuries that are diagnosed too late or not at all due to lack of neurological workup.

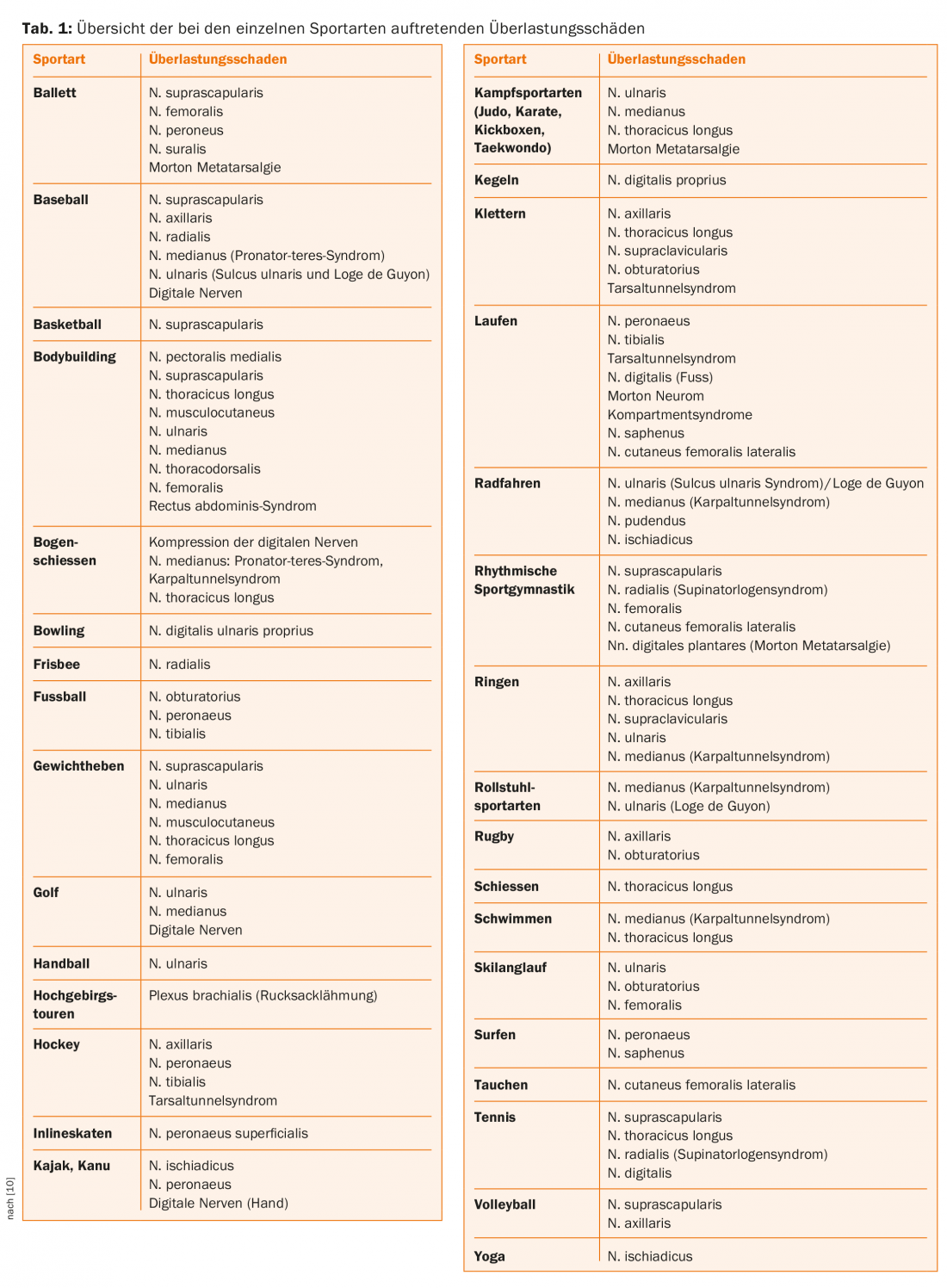

In the present article, particular attention will be paid to sport-related overload damage to peripheral nerves, which plays a greater role with increasing training volumes and can significantly impair the athletes’ fitness for sport. Table 1 provides an overview of the possible nerve overload damage in the various sports. In addition to competitive athletes, ambitious amateur athletes in particular represent a risk group, as they often have poorer technique when practicing their sport, acute overloads are more likely to occur with less well-established build-up and endurance training, and they often receive less good sports medicine care.

Diagnosis

For the diagnosis of overuse damage to peripheral nerves, knowledge of the motion sequence during exercise is particularly important, in addition to medical history and symptoms. For this purpose, it may well be useful to examine the athlete during and after the practice of the sport. In addition to the clinical examination, a neurophysiological examination is often required to confirm the diagnosis and plan therapy. Depending on the symptoms, nerve damage caused by structural changes in bones, joints and soft tissues must be ruled out as a differential diagnosis and additional X-ray examinations, computer tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or sonography must be used. MR neurography can reveal damage to peripheral nerves at a very early stage. Conventional EMG may not show changes until after three weeks, but it can reveal subtle neurogenic muscle damage that may escape clinical detection during strength testing – especially in very well-trained athletes.

In the following, some typical overuse neuropathies occurring during the practice of certain sports are described, which are caused by the specific load of the respective sport. Peripheral nerve damage is a result of either repetitive stretching or nerve compression due to sport-specific muscle hypertrophy. Acute injuries, e.g., from blunt or sharp trauma, are not addressed or are addressed only in passing.

Shoulder and upper extremity

Shoulder injuries are most common in throwing disciplines as well as numerous ball sports (handball, basketball, volleyball, tennis, water polo) and all martial arts. The shoulder is particularly at risk not only in the case of falls by racing cyclists and mountain bikers, but also in all skiing sports. Nerve injuries to the arms are relatively common in all of the sports just mentioned and must be considered, especially when healing is delayed after fractures. A particular predilection site, in addition to the shoulder, is the elbow. Overuse-related nerve lesions are also more common in swimmers with a high weekly workload. Peripheral nerve damage can result – especially to the upper extremity – from surgical intervention performed as a result of a sports injury.

Radial nerve: The most common damage to the radial nerve is overuse injury, especially in sports involving rackets with repetitive pronation and supination such as tennis, squash, table tennis, badminton, and in swimming, baseball, throwing disciplines, golf, and weightlifting.

Supinator ligament syndrome can occur particularly in tennis players, throwers, and swimmers. In the differential diagnosis between supinator ligament syndrome without neurological deficits and epicondylitis, the severe pressure pain at the nerve passage through the supinator muscle can help. In epicondylitis, the pressure pain is found directly at the epicondyle. In addition to electrophysiological diagnostics, sonographic imaging of the nerve may also be useful. Therapeutically, the first priority is conservative treatment with immobilization in 45° flexion, physiotherapy and administration of anti-inflammatory drugs. Surgical measures are required in case of non-response or impending chronification.

Median nerve: Damage to the median nerve is divided into three main constriction syndromes, all of which can occur more frequently in certain sports: pronator teres syndrome, interosseus anterior n erve syndrome and carpal tunnel syndrome.

Pronator-teres syndrome can develop in sports that require firm fist lock and repetitive pronation movements with simultaneous elbow extension: Throwing sports, e.g., javelin throwing, tennis playing, weight lifting, gymnastics (barre gymnastics), baseball (pitching), and contact sports.

Isolated interosseous anterior nerve syndrome, although rare in athletes, is observed in throwers, especially with excessive strength training of the forearm muscles, such as with the hand expander.

Treatment of both pronator teres syndrome and interosseous anterior nerve syndrome includes abstinence from sports, immobilization of the arm at 90°, combined with antiphlogistic treatment. Prognosis is generally good in the absence of trauma; neurolysis must be considered in the absence of recovery after six to eight weeks.

Carpal tunnel syndrome: pressure damage can result from repeated bending and extending movements of the wrist, especially in tennis, squash and badminton players with poor technique, furthermore in archery, golf, baseball, weightlifting or body building. Another mechanism of damage is the pressure on the median nerve when weight is applied to the extended hand, e.g., when cycling while standing and when climbing hills. Wheelchair athletes frequently suffer from carpal tunnel syndrome, with 70% of athletes having prolonged distal motor latency and 30% having manifest carpal tunnel syndrome. At first, there is usually severe pain in the arm at night, and later also during the day. In addition to numbness and paresthesias in the area of the three radial fingers, atrophy of the lateral ball of the thumb with weakness of thumb abduction and opposition is found in advanced symptomatology. Electrophysiological diagnostics and sonography of the median nerve in the carpal tunnel are usually useful. Conservative therapy includes immobilization in a splint, administration of anti-inflammatory drugs, local administration of cortisone, and improvement of technique when practicing sports (improvement of riding technique when cycling, improvement of hand position, improvement of stroke technique). If conservative therapy fails, surgical treatment is indicated.

Ulnar nerve: Lesions of the ulnar nerve in the elbow region occur mainly in throwing disciplines. Cross-country skiing can also result in ulnar nerve damage in the elbow area due to heavy use of ski poles while running uphill. Therapeutically, conservative treatment with anti-inflammatories, splinting, technique training, e.g., with modification of the throwing technique or stick technique, is initially recommended. Neurolysis should be performed if conservative therapy fails.

The cause of distal ulnar nerve compression is pressure from prolonged hyperextension at the wrist, e.g., cycling, sport climbing, gymnastics, or from a forceful arm thrust during cross-country skiing and in wheelchair athletes. Injuries to the distal ulnar nerve further occur from ball impact in baseball catchers and from pressure during weight lifting exercises.

Distal ulnar nerve lesion is popularly referred to as cyclist’s palsy. Factors contributing to so-called cyclist paralysis include ill-fitting or worn cycling gloves, insufficient handlebar padding, too little change in hand position, or poor seating position with too much weight on the hands. In cycling, hand position and pressure on the handlebars are critical to the development of a distal ulnar lesion.

Treatment of distal ulnar nerve compression syndrome is generally conservative. Hand and handlebar position while cycling should be changed, in addition padding and wearing gloves are recommended. In case of severe discomfort, temporary relief by splinting and cortisone administration may also help.

Peripheral nerve lesions on the lower extremity

Damage to peripheral nerves in the legs occurs primarily during cycling and all running sports.

Pudendal nerve: Compression of the pudendal nerve is particularly common in cyclists due to prolonged sitting on a narrow and hard bicycle saddle. A stint of several hours of cycling per week for many years is considered an independent risk factor for erectile dysfunction (ED).

Diagnostically helpful can be the derivation of somatosensitive evoked potentials (SSEPs). The use of laser Doppler flow measurement in recent studies confirmed the influence of saddle position on blood flow. To prevent ED, a saddle position with a slight downward tilt, a reduction in the height difference between the handlebars and the saddle, and the ability to support weight by slightly bending the legs at the lowest crank point are recommended.

Femoral nerve: Clinically, femoral nerve damage can result from both partial lesion of the lumbosacral plexus and damage in the more peripheral course. Ischemic plexus damage with predominant femoral nerve damage has been described in older athletes with severe spondylosis. Compression of the femoral nerve during heavy uphill cycling has been reported, particularly in male senior athletes; there may be an additional vascular component in these cases. Electrophysiologic studies are required to differentiate from plexus palsy. MRI examination can be used to rule out external compression. The prognosis is good in the case of overuse injuries; training must be reduced accordingly and consistently after the onset of symptoms; in addition, physiotherapy is recommended.

Sciatic nerve: Pressure lesions of the sciatic nerve can occur, especially in thin individuals, from prolonged sitting during cycling, rowing, and kayaking, and less commonly during long-distance horseback riding, after prolonged sitting in the lotus position (yoga), or during weight training. The site of the lesion is usually in the region of the piriformis muscle; in addition to pain in the buttocks, paresthesias of the feet occur. If symptoms are disregarded and athletic activity is continued, foot lifter paresis may occur. Differential diagnosis must exclude inflammation of the ischiadic bursa, which is associated with gluteal pain and ischialgia, and inflammation of the ischiogluteal bursa, which produces distally radiating pain on the inner thigh. Electrophysiology, sonography, and MRI examinations are useful for clarification. Therapy is generally conservative with muscle building training and by changing the seating position when cycling or boating.

Peroneal nerve: compression of the nerve can occur at different levels:

- Pressure on the fibular head, e.g., by leaning on the edge of a boat (kayak, folding boat) or stretching the nerve when the knee joint is unstable, can cause damage to the common peroneal nerve.

- When entering the peroneal arch under the peroneal longus muscle, compression of the nerve may occur due to injury to the knee joint or, for example, due to a Baker’s cyst.

- Compression can be caused by the fascia of the peroneal longus muscle, especially in runners with rapid increases in training volume and overpronation of the foot, or in long surfing due to prolonged abduction of the leg and pronation of the foot.

- Compression of the superficial peroneal nerve usually occurs as it passes through the lower leg fascia above the ankle joint. Causes include sharp fascial edges, repeated distortions of the ankle and tight footwear, such as ski, mountain, ice skates or tightly laced dance shoes.

Clinical examination and history guide the diagnosis of peroneal nerve compression, and electrophysiologic examination may be helpful in accurately localizing the site of injury and excluding proximal lesions such as radiculopathies or plexus lesions. An MRI scan is recommended if abnormalities are suspected in the knee joint and if the profundus peroneal nerve is compressed under the ligament. cruciatum helpful. Ultrasound examinations are suitable for detecting structural soft tissue changes in the area of the lower leg.

Therapeutically, all measures that reduce the pressure on the corresponding part of the nerve can be considered: running training, technique training, physiotherapy, in case of compression from the outside padding (boot rim, ski boots) and renouncement of high shoe lacing (ballet). In addition, anticonvulsants (neuromodulatory, membrane-stabilizing) or local injections of cortisone combined with lidocaine may help with severe pain. Surgical therapy should be performed in cases of compression of the nerve by ganglia and intraneural cysts to prevent axonal damage.

Damage to the profundal peroneal nerve may further occur in the so-called functional compartment syndrome (tibialis an terior syndrome or anterior compartment syndrome) of the lower leg. The result is foot and toe lift paresis and sensory disturbance in the first interdigital space. This is caused by unaccustomed extreme athletic stress or extreme running stress in the high-performance range (running uphill, running up stairs). Mild forms can be treated with exercise reduction; advanced symptoms require fascia splitting.

Tibial nerve: Typical compression syndromes of the tibial nerve are tarsal tunnel syndrome and Morton’s metatarsalgia.

Tarsal tunnel syndrome: Running and jumping are predisposing sports for the development of tarsal tunnel syndrome, but judokas and friction climbers (extreme dorsiflexion) may also be affected. Runners who pronate heavily and twist their ankles more frequently while running are at higher risk of developing tarsal tunnel syndrome. Likewise, an ill-fitting running shoe can cause or worsen the symptoms of tarsal tunnel syndrome.

Differential diagnoses include plantar fasciitis (symptoms more severe in the morning), posterior compartment syndrome, tendonitis, ganglions, vascular causes, joint inflammation, and polyneuropathies. In isolated compression of the medial plantar nerve (“joggers foot”), there is a load-dependent pain in the area of the medial heel and longitudinal arch with radiation to the medial toes and ankle joint. The differential diagnosis must include tendovaginitis of the M. flexor hallucis longus should be considered. Sensory nerve conduction velocity (NLG) recording is more sensitive than motor NLG recording for diagnostic purposes. The examination is technically difficult; if the derivation is successful, abnormal findings are found in 90% of patients with tarsal tunnel syndrome.

Normal examination findings do not rule out tarsal tunnel syndrome in a typical clinic, in which case a diagnostic conduction block of the tibial nerve may help. An MRI scan should be performed to rule out a space-occupying lesion in the tarsal tunnel, arthritis, or a stress fracture.

Therapy is primarily conservative with reduction or modification of athletic exertion, change in running style, heel elevation and heel padding, orthotic fitting, possibly with pronation support, physical therapy, anti-inflammatories, and neuromodulatory medication (tricyclic antidepressants, anticonvulsants). Local injections with cortisone under ultrasound guidance followed by weight relief may result in good outcomes. Most authors recommend surgery only after 6-12 months of conservative therapy.

Morton Metatarsalgia: Morton metatarsalgia is a pain syndrome first described by Morton and caused by small neuromas or more precisely pseudoneuromas of the digital nerves. Runners with extreme mileage or ballet dancers are often affected. Unaccustomed long runs can trigger the symptoms even in those with lower weekly mileage. Injection of local anesthetic eliminates the pain, removal of the shoe and massaging the forefoot also bring relief. In most cases, the complaints are typical, so that further imaging examination is not necessary. If this is done, the neuroma can often be detected directly on MRI examination and also on ultrasound.

Therapy initially consists of conservative measures such as insoles with retrocapital support, physiotherapy, improvement of Achilles tendon flexibility, gait training, administration of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and infiltration with local anesthetic and cortisone under sonographic control. Training reduction or training with weight relief (training in water, on the bike or on the treadmill with weight relief) is usually necessary. In cases of therapy-resistant symptoms and a definite diagnosis, surgical intervention is recommended.

Disclaimer Acknowledgement: This article is based on two of our papers [9,10], parts of which have been adapted for this paper.

Literature:

- Reuter I, et al: Peripheral nerve bottleneck syndromes in athletes. Sportverl Sportschad 2013; 27: 130-146.

- Hainline BW: Peripheral nerve injury in sports. Continuum 2014; 20: 1605-1628.

- Mitchell CH, et al: MRI of sports-related peripheral nerve injuries. Am J Roentgenol 2014; 203: 1075-1084.

- Cass S: Upper extremity nerve entrapment syndromes in sports: an update. Curr Sports Med Rep 2014; 13: 16-21.

- Meadows JR, et al: Lower extremity nerve entrapments in athletes. Curr Sports Med Rep 2014; 13: 299-306.

- Russels CR: Therapy challenges for athletes: splinting options. Clin Sports Med 2015; 34: 181-191.

- Hausner T, et al: The use of shock waves in peripheral nerve regeneration: new perspectives? Int Rev Neurobiol 2013; 109: 85-98.

- Harris JD, et al: Nerve injuries about the elbow in the athlete. Sports Med Arthrosc 2014; 22: 7-15.

- Tettenborn B, et al: Sports injuries of peripheral nerves. Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr 2016; 84: 1-17.

- Tettenborn B, et al: Sports injuries of peripheral nerves. Clinical Neurophysiology 2016; 47: 57-77.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2016; 14(6): 4-10.