Depressive disorders are among the most common mental illnesses, and many older people also suffer from them. Nowadays, a biopsychosocial explanatory model is assumed. In addition to psychotherapy and general psychosocial measures, geriatric patients may also benefit from therapy with antidepressants. Carefully tailored treatment to the individual patient and his or her current situation is important, including consideration of multimorbidity and polypharmacy.

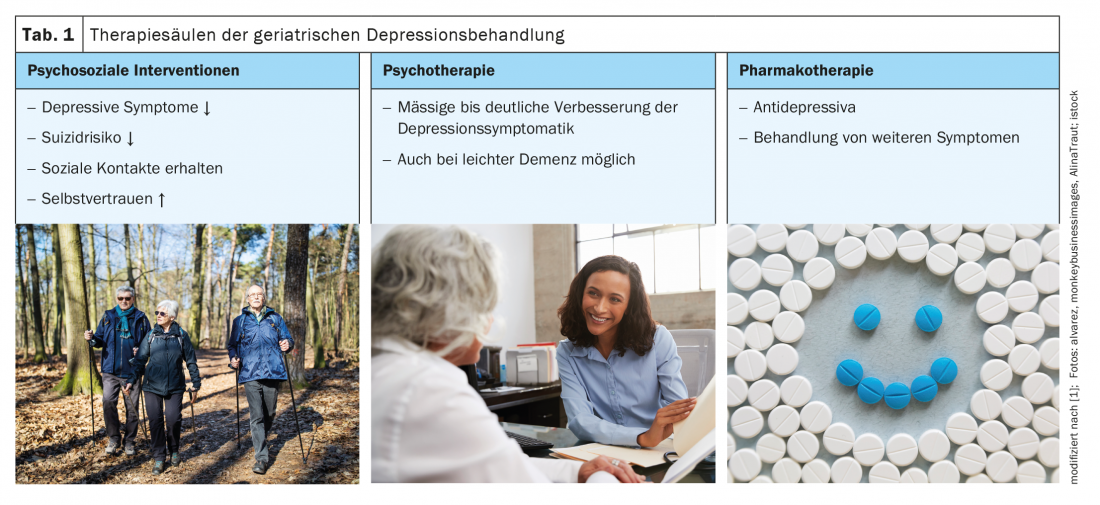

The causes and risk factors for depressive disorders in old age are biopsychosocial. Many patients find it difficult to cope with increasing dependence and an associated loss of autonomy, explains Birgit Schwenk, MD, Chief Geriatrician, Rheintal/Werdenberg/Sarganserland Hospital Region [1]. The loss of social roles and caregivers or of the familiar home environment, as well as age-correlated physical complaints, are further aspects that threaten depression. Certain medications can also induce depressed mood. Depressive disorders of all severities are common in old age, with a prevalence of 25% in the over-65 age group, she said. With increasing frailty, the proportion of depressive disorders also increases [2]. The consequences are often severe, ranging from cognitive impairment to reduced independence, nursing home admission, and suicidality. Treatment of depression in geriatric patients includes the three pillars of psychotherapy, antidepressants, and psychosocial measures (Table 1).

Frequent atypical symptomatology in geriatric patients.

It should be noted that in old age depression presents itself somewhat differently than in other age groups. According to ICD-10, the main symptoms of depressive disorder are known to be depressed mood, loss of interest and joylessness, as well as lack of drive and increased fatigability [3]. According to this classification, various additional symptoms may be present, such as difficulty concentrating, impaired self-esteem, feelings of guilt, pessimistic outlook, suicidal thoughts and actions, or sleep disturbances. One of the special features of depressed geriatric patients is that somatization tendencies are often in the foreground; another is that those affected usually make a grumpy and irritable impression, explains Dr. Schwenk. Since corresponding symptoms are often classified as normal due to age, depression in old age often remains untreated. As a time-saving depression screening tool for family practice, the speaker recommends the two-question test:

- Have you often felt down, sad, depressed, or hopeless in the last month?

- In the last month, have you had significantly less desire and pleasure in doing things you usually enjoy?

If a depressive disorder is suspected, a more detailed diagnosis consisting of history and clinical examination is advisable, including standardized questionnaires. Designed for use with older people are the self-report questionnaires GDS (Geriatric Depression Scale) and DIA-S (Depression in Aging Scale) [4–6]. Furthermore, a large blood count is also part of the clarification. The speaker mentions dementia or hypoactive delirium as important differential diagnoses to depressive disorders. Untreated depression can often result in suicide as people age, although it is often unannounced, the speaker reported [1].

Which antidepressant for which patient?

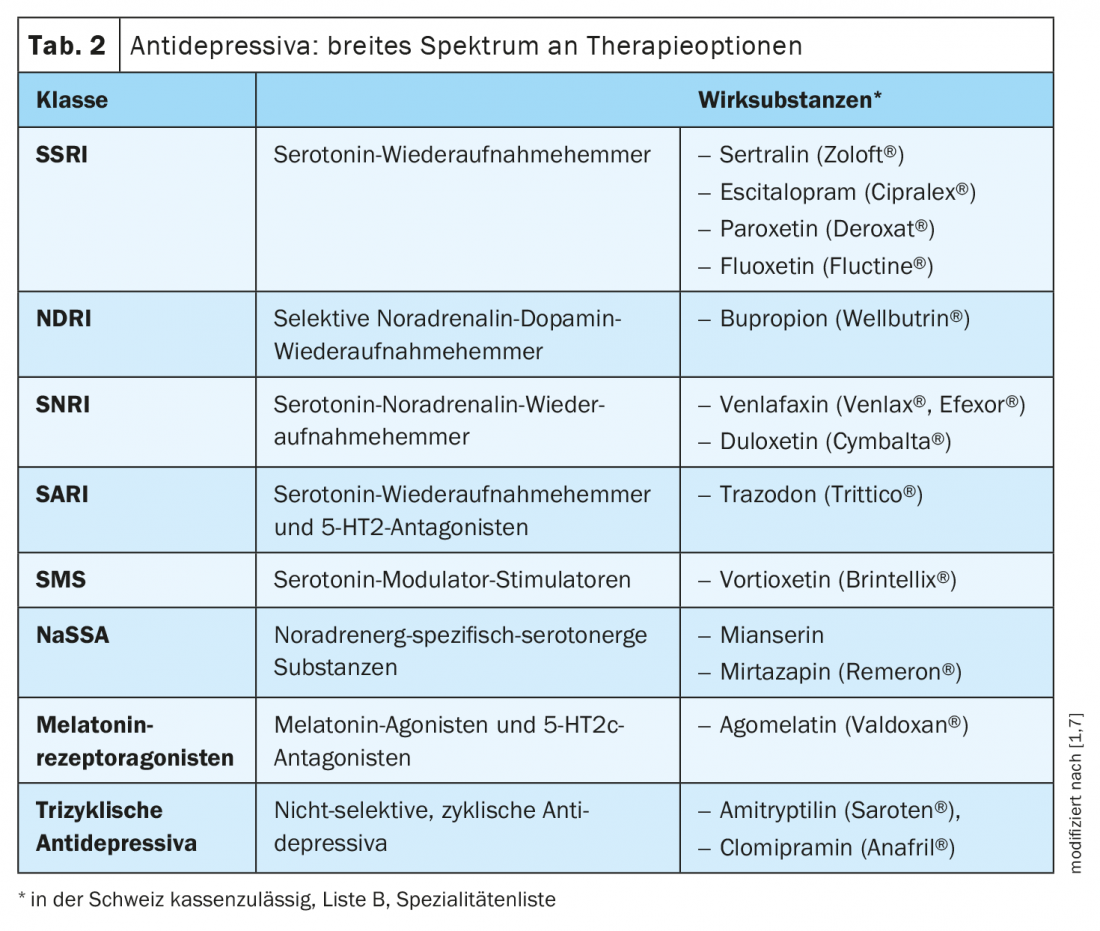

The spectrum of antidepressant medications is very broad nowadays (Table 2) [1,7]. From the group of serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), Dr. Schwenk prefers to use citalopram, escitalopram and sertraline. One should keep an eye on possible hyponatremia as a side effect with these substances. Sertraline has the most favorable benefit-risk profile of this group of active ingredients. Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) are also an important class of antidepressants, especially for comorbid pain problems, she said. However, a “restless legs” syndrome can occur as an accompanying symptom. Among dual-serotonergic antidepressants (SARIs), whose mechanism of action combines serotonin reuptake inhibition with 5-HT2 antagonism, trazodone is well suited for elderly patients because it is beneficial for cognition and has sleep-promoting effects. From the class of melatonin receptor agonists, evidence of efficacy for agomelatine up to age 75 years is available from a placebo-controlled trial and various open-label clinical trials [8]. Due to the melatonergic effect, this active substance is sleep-promoting, and cognition is also positively influenced [4]. The side effect profile has also been shown to be favorable, although liver enzymes should be monitored regularly [9]. A multimodal antidepressant is vortioxetine, a member of the serotonin modulator-stimulator class. Positive evidence of efficacy is also available for this antidepressant up to the age of 75 years [10]. In geriatric patients, it is particularly important to adapt psychopharmacological treatment to individual conditions. “It’s always an individual therapy,” the speaker said.

Multimorbidity and polypharmacy must be taken into account

The issue of polypharmacy plays an increasingly important role in old age. Apart from the side effect profiles, interaction potentials must therefore also be given special attention. This should be taken into account by using it according to the indication and slowly titrating it up. The basic rule ‘start low, go slow’ is particularly important in this patient population, he said. Under what conditions should special care be taken? In patients with diabetes, the substances paroxetine and mirtazapine are unfavorable because they have appetite-stimulating effects and can lead to weight gain. Furthermore, the use of venlafaxine should be avoided in arterial hypertension due to a possible blood pressure-increasing effect. “Generally unfavorable in the elderly are the tricyclic antidepressants, because of the side effects,” Dr. Schwenk adds. In addition to bladder weakness, potential adverse effects of this class of agents include cognitive impairment and delirium. St. John’s wort preparations are also rather unfavorable, due to the potential for interaction.

In general, it should be noted that the onset of action of antidepressants can take from a few days to four weeks, so some stamina is required [1]. Mild side effects are common at the start of therapy (e.g., nausea), even with antidepressants that are otherwise well tolerated. What to do in case of insufficient effectiveness? The first thing to do is to increase the dose. If this does not help, consider switching to another antidepressant, possibly combining two medications. Furthermore, augmentation (lithium, antipsychotics) could be considered in collaboration with a psychiatrist. For antidepressant maintenance therapy, Dr. Schwenk recommends a duration of 6-9 months at a consistent dosage [1]. When therapy is discontinued, the antidepressant must be phased out to avoid discontinuation phenomena as much as possible.

Congress: College of Family Medicine 2021

Literature:

- Schwenk B: Therapy of depression in old age from a geriatric perspective. Birgit Schwenk, MD, College of Family Medicine, June 24-26, 2021.

- Kopf D, Hummel J: Depression in the frail elderly patient. Diagnostics and therapy. Z Gerontol Geriatr 2013; 46(2): 127-133.

- World Health Organization: ICD-10, https://icd.who.int (last accessed Aug. 20, 2021).

- Hatzinger M, et al: Recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of depression in the elderly. Praxis 2018; 107(3): 127-144.

- Gauggel S, Birkner B: Validity and reliability of a German version of the Geriatric Depression Scale. Z Clin Psychol 1999; 28: 18-27.

- Heidenblut S: Depression diagnosis in geriatric patients. The development of the Depression in Aging Scale (DIA-S). PhD thesis; University of Cologne: 2012.

- Drug Information, www.swissmedicinfo.ch, (last accessed Aug. 20, 2021).

- Heun R, et al: The efficacy of agomelatine in elderly patients with recurrent major depressive disorder: a placebocontrolled study. J Clin Psychiatry 2013; 74: 587-594.

- Howland RH: A benefit-risk assessment of agomelatine in the treatment of major depression. Drug Saf 2011; 34: 709-773.

- Häggström L, et al: Randomized double-blind study of vortioxetine versus agomelatine in adults with MDD after inadequate response to SSRI or SNRI treatment. Eur Psychiatry 2013; 28(Suppl 1): 1.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2021; 16(9): 30-31 (published 9/18-21, ahead of print).

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2021; 19(6): 36-37.