The SGAMSP Annual Meeting in Liestal focused on the psychological and physical factors in the course of the disease. Particularly in polymorbid patients treated with psychotropic and somatic medications, there is a potential risk of adverse drug reactions (ADRs). The reason for this may be interactions of active ingredients that need to be controlled or avoided. However, psychological factors that play a role in ADR must also be taken into account.

Patients with complex physical and mental disorders are a major challenge for pharmacotherapy. These are mainly patients of the schizophrenic and affective types, called patients with SMI (severe mental illness). They have an increased risk of mortality as well as a more frequent occurrence of somatic comorbidities. This patient group was the focus of the presentation by Philipp Eich, MD, Chief Physician, Centers for Crisis Intervention and Dependence Disorders, Psychiatry Baselland.

Routine somatic examinations in patients with SMI.

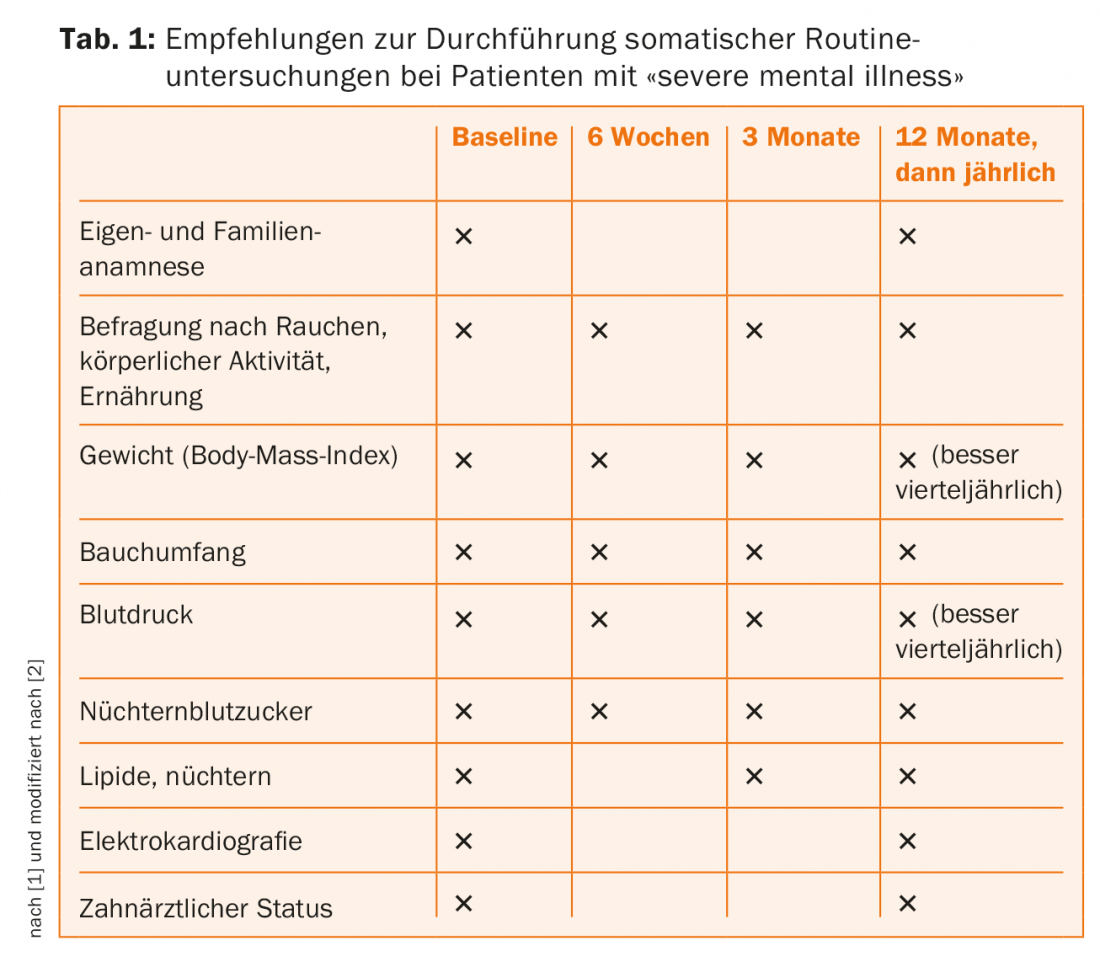

Patients with SMI require thorough somatic evaluations in addition to psychiatric care. Common comorbidities in these patients include cardiovascular, endocrinologic, musculoskeletal, renal, gastrointestinal, neurologic diseases to infections such as AIDS and chronic ovarian inflammation. Against this background, there are recommendations for carrying out routine somatic examinations: This includes a self and family history at the beginning of treatment, followed by regular questioning about smoking, physical activity and diet. Weight, abdominal circumference, blood pressure and fasting blood glucose should also be measured regularly. At the beginning of the treatment, it is also recommended to perform an electrocardiography and also to record the dental status (Tab. 1) [1].

New diagnosis “Somatic Stress Disorder

To improve somatic health care for patients with SMI, it is important to focus on the links between mental and physical health. Currently, changes in the terminology of psychosomatic disorders are taking place [3]. These reflect the current understanding of these diseases and thus facilitate the therapeutic approach. In the 5th edition of the “Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders” (DMS-5) published in 2013, somatoform disorders, somatization disorder, hypochondriasis, and pain disorder were abolished. The 11th edition of the “International Statistical Classification of Diseases” (ICD-11), scheduled for 2018, will also no longer list somatoform disorders.

Newly introduced in the DSM-5 is the diagnosis of “Somatic Symptom Disorder,” which translates as “Somatic Stress Disorder.” The diagnostic criteria include three points that must be met: Criterion A is somatic symptoms that are distressing or lead to disruptions in everyday life. Criterion B identifies psychological features (excessive thoughts and feelings) related to physical symptoms, and criterion C is persistent symptom burden (usually longer than 6 months). The new diagnosis is intended to express that many patients have severe somatic symptoms that cause them to be significantly or very stressed and experience numerous impairments in their daily lives. Also newly named in DSM-5 are the previous hypochondriacal disorder (Illness anxiety disorder) and dissociative neurological disorders (Conversion Disorder).

Do not forget the psychosocial dimension

Philipp Eich, MD, emphasizes that in complex disorders (physical and psychological), the therapeutic relationship is more important than the therapy method. It should also be noted that the psychosocial dimension is easily forgotten and patients themselves tend to have one-sided somatic disease hypotheses. Any pharmacotherapy should therefore first be comprehensively clarified and the diagnosis discussed with the patient. Furthermore, he must be informed in detail about the therapeutic measures. Because these patients often receive treatment from multiple physicians, there is a risk of polypharmacy. This situation requires careful therapeutic drug management (TDM) and good collaboration between primary care physicians and psychiatrists.

Psychotropic drugs (antidepressants) are helpful when there is a clear indication and suffering. When prescribing medications, keep it simple, i.e., as few pills and times of intake as possible. In dual disorders, “back and forth” about which disorder to treat first should be avoided. Antipsychotics/neuroleptics should be prescribed only with clear indication, and not used as hypnotics. For chronic pain conditions, it is important to note that NSAIDs and opiates are not prescribed uncritically.

Psychological adverse events: what package inserts can do

The pharmacist Dr. sc. ETH David Niedrig, Zurich Children’s Hospital, Drugsafety.ch, addressed possible triggers of psychological adverse drug reactions (ADRs) in his presentation. He described the case of a 25-year-old depressed patient to whom the physician prescribed Deroxat [4]. After two weeks there is good tolerance, UAW are hardly present. After four weeks, Deroxat is replaced by a generic drug. Two weeks later, the patient presents to the practice as an emergency and reports side effects with dizziness and nausea. After switching back to the original preparation, the symptoms promptly disappear.

There is no rational explanation, as the generic was co-marketed and is identical to the original except for name and packaging. (Co-marketing products are listed on the Swissmedic website). The question here is whether these are side effects or a nocebo effect triggered by formulations on the package insert. As an example, the speaker mentions the information on the antihistamine cetirizine: While the specialist information mentions mild adverse effects on the CNS, the package insert informs patients as follows: “Caution is advised when driving a motor vehicle or handling machinery, as taking cetirizine can make you drowsy”. A look at the safety data from clinical trials shows that somnolence occurs with an incidence of 9.63% with cetirizine, compared to 5.00% with placebo. Interesting in this context are placebo-controlled studies with children (from 6 months to 12 years): Adverse effects with cetirizine are reported in them at 1.8%, with placebo at 1.4%.

The decisive factor is communication

In research, it is important to consider the mechanisms of nocebo effects because they can bias the outcome of clinical trials. This was described in a recent review [5] using pain patients who were administered a NaCl solution or the opioid analgesic remifentanil: If they received remifentanil, and this was communicated, the pain decreased strongly, as expected; with remifentanil, declared as NaCl, the pain relief was considerably lower. When subjects were told during remifentantil therapy that the infusion had been interrupted, but this was not true, pain that had already subsided re-intensified.

The Internet can also play a role in the development of psychological ADRs: Whereas doctors and pharmacists used to be the gatekeepers of information, patients now use the Internet to exchange information about the satisfaction, efficacy, and side effects of medications. On the corresponding websites, the latter are listed unfiltered. For uninformed patients, therefore, the Internet is a “catalyst” for nocebo, says Dr. David Niedrig. The goal of physicians and pharmacists must be that patients trust the information provided by the specialist more than the information from the Internet or on the package insert.

Nocebo can be avoided if potential side effects are communicated “well”: The proven benefit and, if applicable, the many years of clinical experience should be emphasized and contrasted with specific and also non-specific ADRs. It is also helpful to mention that the package insert is primarily a “regulatory legal document” and to refer to therapeutic equivalence in the case of generic drugs.

Source: Swiss Society for Drug Safety in Psychiatry SGAMSP, 14th Annual Meeting, September 29, 2016, Liestal.

Literature:

- Hewer W, et al: Somatic morbidity in the mentally ill. Der Nervenarzt 2016/7.

- De Hert M, et al: Physical illness in patients with severe mental disorders. World Psychiatry 2011 Feb; 10(1): 52-77.

- Von Känel R, et al: Somatic stress disorder: stress from body symptoms. Primary and Hospital Care 2016; 16(10): 192-195.

- Lauterburg BH, et al: Generic or original product? Primary Care 2005;5: 39

- Benedetti F, et al: Increasing uncertainty in CNS clinical trials: the role of placebo, nocebo, and Hawthorne effects. Lancet Neurol 2016 June; 15(7): 736-47.