Adverse events following vaccination are common, but only a small proportion are true vaccine side effects. Adverse events falsely classified as vaccine side effects prevent adequate treatment of the actual underlying disease. Therefore, if a “vaccination side effect” is suspected, careful exclusion diagnostics should always be performed. Prior to any vaccination, the person to be vaccinated or their surrogates must be informed of the benefits and risks of the planned vaccination(s).

Nobody loves “undesirable events” and yet they shape our everyday lives because of their frequency. In the medical context, in terms of pharmacovigilance in the context of drug administration including vaccination, we need to distinguish adverse events following immunization (AEFI) from side effects. The first of the two terms is deliberately very broad and allows monitoring of the safety of drugs and remedies, including vaccines, with high sensitivity because temporal association is sufficient for suspicion, regardless of a presumed causal link. For this, the specificity is rather low. For example, a collapse ten minutes after a vaccination is initially classified as an adverse event. If no other plausible cause than the vaccination applied shortly before explains the event, there is a suspicion of a side effect, i.e. a causal link with the vaccination. However, the causal relationship cannot always be proven beyond doubt or excluded, which is particularly true for systemic reactions.

In contrast, local reactions such as redness or swelling at the injection site within a biologically plausible time interval (from experience, a few hours to a few days) are typical examples of definite vaccine side effects.

In pharmacovigilance terminology, the term “adverse drug reaction” (ADR) is readily used for adverse events. It implies a causal relationship (drug effect) without this being a priori certain.

“Fiction and truth” – why this unusual addition to the title of this article? I chose it because real side effects (“truth”) are much rarer than commonly thought. Most adverse events have a cause other than the preceding vaccination(s) and therefore must be attributed to “seal” in the context of pharmacovigilance. Sometimes, however, it takes some time before the corresponding events are unmasked as “pseudo side effects”. For the affected patient, this clarification process is of enormous importance, because only the successful search for the true cause of the event opens the option for a causal treatment, whereas with the erroneous diagnosis of “vaccination side effect” one often shrugs one’s shoulders in resignation with regard to therapy. A classic example is the “pertussis vaccine encephalopathy” frequently cited in the 1990s, which only turned out to be a fiction after years of painstaking research [1,2]. The then-common pertussis whole vaccines proved innocent of the postulated CNS manifestations and have therefore long been rehabilitated [3].

Truth (or reality)

No medical device has absolute safety in its use, including vaccines, so we cannot guarantee the absence of side effects to ourselves or our patients. But this should not make us pessimistic, because the vaccines available today have a very high level of safety, higher than ever before in their development history. This is the responsibility of the researchers, the manufacturers and, as the last and decisive link in the quality assurance chain, the regulatory authorities, in Switzerland Swissmedic.

In discussions with vaccine-critical individuals, the high level of vaccine safety is unfortunately often not emphasized enough, although it is a strong argument for vaccination per se. The main reason for the significant increase in safety over the last two to three decades is the size of the clinical trials conducted: vaccines are no longer tested on just a few hundred volunteers, but usually on tens of thousands [4]. Approval from a vaccine safety perspective (efficiency or efficacy must also be demonstrated, of course) is only granted if the type and frequency of significant adverse events or side effects in vaccinated individuals do not differ significantly from control participants.

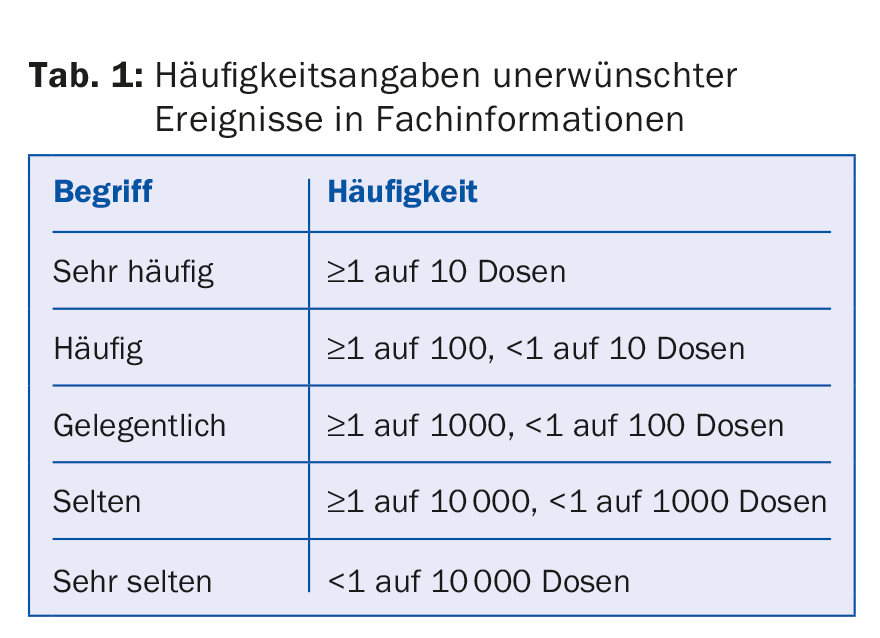

Based on careful investigations of the reported suspected cases of vaccination side effects, we know that these account for a rather small proportion of adverse events. However, public perception overestimates the frequency of vaccine adverse events, not least because the frequency terms defined in pharmacovigilance invite overinterpretation by laypersons (Table 1).

Side effects facts

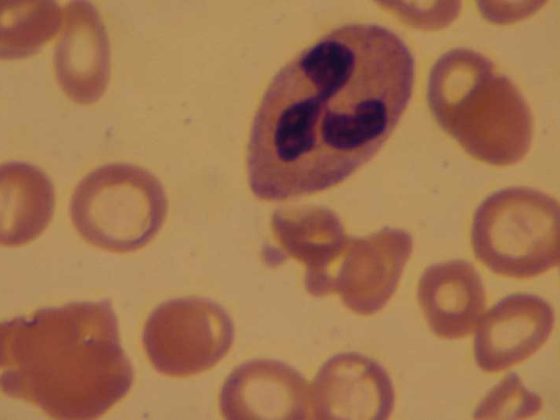

Vaccinations may cause typical side effects at the vaccination site (e.g., redness, swelling, pain) that are generally temporary and easily tolerated. The probability of their occurrence depends on the type of vaccination and the number of previous vaccination doses. With inactivated vaccines (i.e., containing inactivated infectious agents or specific antigens), local side effects are observed with increasing frequency from dose to dose, whereas the age of the vaccinated person tends to play a subordinate role. They do not require further clarification unless the patient’s general condition is significantly impaired.

Systemic reactions, such as fever in the first 24-48 hours after vaccination, on the other hand, require a detailed examination of the vaccinated person in order to be able to recognize and, if necessary, treat coinciding other diseases in a differential diagnosis. Treatment is otherwise limited to symptomatic measures (e.g., antipyretics).

After administration of live vaccines (attenuated, reproducible infectious agents, e.g. measles-mumps-rubella, varicella), vaccine sickness may occur in addition to local side effects at the vaccination site, usually in the first 48 hours (at the earliest on the fourth to fifth postvaccinal day, i.e. after the incubation period has elapsed). This resembles in attenuated form the actual disease caused by the wild-type virus. These include, for example, a transient exanthema (vaccine measles, rubella, or varicella) or a unilateral or bilateral, usually mild parotid swelling (vaccine mumps). These manifestations are of short duration (one to two days), harmless and generally not contagious. Therefore, they do not require specific therapy or isolation of the vaccinee.

Informative talk before vaccinations

Prior to any vaccination, the person to be vaccinated or their legal representatives must be informed of the benefits and risks of the planned vaccination(s). The reconnaissance should meet the following requirements:

- It must be performed by a physician.

- The extent and intensity depend on individual circumstances, i.e. patient-related, taking into account the linguistic and intellectual level.

- Sufficient time must be available, i.e. the person to be informed must have the opportunity to ask questions.

- It must be oral, although written information (e.g., in the form of a fact sheet) is permitted in advance and is often useful.

- It must indicate the voluntary nature of the planned vaccination(s); it must not give the impression that the vaccination(s) is an unavoidable “must”.

In terms of content, it is advisable to address the following points during the educational interview:

- Presentation of the benefits of the planned vaccination(s), i.e. information on the expected success of the vaccination, as well as the factual presentation of the possible consequences of the disease if the corresponding vaccination is not given;

- Point out any alternatives to vaccination that may be available (e.g., exposure prophylaxis, chemoprophylaxis, etc.);

- Type and number of vaccinations needed to achieve complete immune protection;

- Indication of necessary precautions to be taken after vaccination by the vaccinee himself or by his contacts (e.g. avoidance of contact with immunocompromised persons after varicella vaccination);

- Nature and frequency of possible side effects and their consequences. This must include all known side effects, whereby the content of the respective expert information is authoritative.

The education may take place immediately before the planned vaccination. A longer cooling-off period is not required. Following the educational interview, formal consent to vaccination must be obtained. This can be done orally. However, it is advisable to document the content and scope of the informed consent discussion as well as any witnesses (practice staff) in writing in the patient records.

Obligation to report

Any unexplained post-vaccinal adverse event is reportable (via pharmacovigilance centers, see www.swissmedic.ch) if it is a threatening condition, it results in drug treatment, or it is a relevant new observation (i.e., not described in the SmPC).

Seal

Nowadays, vaccines are often the subject of public criticism because people have become accustomed to their success (decline in vaccine-preventable diseases) and increased attention is paid to their perceived and actual side effects. In the extreme case – the disease is severely repressed, safety concerns are so strong that vaccination acceptance declines and the disease again increases in incidence – successful vaccinations are, in a sense, digging their own grave [5].

We must accept that public tolerance for vaccine side effects is much lower than for medications: Vaccines are administered to healthy individuals, often infants, and any change in their health status as well as behavioral changes are viewed with suspicion, whereas drugs are often administered to sick patients who are suffering and side effects are accepted accordingly.

Often, rumors about alleged vaccine complications or even vaccine damage spread through social media (whether consciously or unconsciously). Mostly, these are general claims, such as vaccinations would lead to autism or multiple sclerosis or generally overload the immune system – these claims are disproved by scientific studies and thus belong to “poetry” [6].

Literature:

- Stehr K, et al: Rehabilitation of pertussis vaccination. Postvaccinal permanent damage: a myth. Pediat Prax 1994; 47: 175-183.

- Cherry JD: ‘Pertussis Vaccine Encephalopathy: It is time to recognize it as the myth that it is. JAMA 1990; 263: 1679-1680.

- Heininger U: The reassessment of pertussis and parapertussis. Studies on the diagnosis, symptomatology, epidemiology and vaccination prophylaxis of contemporary pertussis diseases (Habilitationsschrift). Thieme Verlag: Stuttgart, New York, 1996.

- Koch J, et al: Background paper to the recommendation for routine rotavirus vaccination of infants in Germany. Bundesgesundheitsbl 2013; 56: 957-984.

- Heininger U: The success of immunization-shovelling its own grave? Vaccine 2004; 22: 2071-2072.

- Offit PA, et al: Addressing parents’ concerns: do multiple vaccines overwhelm or weaken the infant’s immune system? Pediatrics 2002; 109: 124-129.

Useful vaccine safety websites:

- Swissmedic: www.swissmedic.ch

- Infovac: www.infovac.ch

- World Health Organization (WHO):

- www.who.int/immunization_safety

- Institute for Vaccine Safety Johns Hopkins:

- www.vaccinesafety.edu

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention USA:

- www.cdc.gov/vaccinesafety/ensuringsafety/monitoring/vsd/index.html

- The Brighton Collaboration: www.brightoncollaboration.org

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2016; 11(6): 8-10