In the case of an initial manifestation, antipsychotic drug treatment should be given for at least twelve months, then continuously for two to five years after any initial relapse. After multiple relapses, lifelong antipsychotic treatment should be considered, taking into account the individual’s motivation and psychosocial situation. The following article discusses in particular the advantages and disadvantages of depot medication in long-term medication and emphasizes the importance of full education about it on the part of the practitioner. Furthermore, polypharmacy is critically examined.

A guideline for schizophrenia treatment valid for Switzerland is currently being prepared. The broadly supported S3 guideline schizophrenia of the German Psychiatric Society DGPPN (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Psychiatrie, Psychotherapie und Nervenheilkunde [1]), which is currently being updated, provides for phase-specific therapy of schizophrenia. The main goal of long-term or maintenance antipsychotic therapy, in addition to symptom reduction, is relapse prevention. On the one hand, as many as 20% of all patients who have experienced a first psychotic episode do not show any further psychotic symptoms in the further course; on the other hand, there are no reliable predictors that could be used to estimate which first-time sufferers will belong to this 20%. Therefore, according to the guideline, “for most people with confirmed schizophrenia,” the administration of antipsychotic medication is indicated beyond the acute phase. The guideline also specifies that antipsychotics should be used for long-term therapy (recommendation strength A).

In cases of multiple manifestations, continuous oral administration is preferable to an intermittent treatment strategy. After symptom remission, the antipsychotic dose in long-term treatment can be gradually reduced over longer periods and adjusted to a lower maintenance dose. For reasons of space, no detailed description of the dosages is given below. Here, reference should be made to the respective intake regulations as well as to the S3 guideline of the DGPPN [1].

Decision about the therapy: “Shared Decision Making

Shared decision making, where the English term “shared decision making” is also often used, can be seen as an ethical imperative [2]. The UK NICE guideline recommends that the choice of medication should be made jointly by the patient and the practitioner [3]. Even if joint decision-making is not usually carried out in a standardized manner, there should at least be a corresponding exchange of information in free conversation, which then allows a well-founded joint decision to be reached. It should be borne in mind that patients and psychiatrists nevertheless have very different perceptions of the actual weighting of the decision, whether more on the patient side or more on the practitioner side [4]: Even though the psychiatrist may have the impression that the decision was made jointly, in quite a few cases the patient will still have the impression that he was pushed to make the decision.

Treatment adherence

Research on adherence to antipsychotic treatment has shown that a significant proportion of prescribed medication is not taken. In one review, the average compliance rate for antipsychotics in patients with schizophrenia was found to be 58%. This is significantly lower than the average rate of 76% for chronic somatic diseases [5]. Given the high risk of relapse of 80% within five years, this seems particularly problematic [6]. At the same time, it has been shown that long-term neuroleptic treatment can significantly reduce the risk of relapse [7]. A meta-analysis [8] of 65 trials with a total of 6493 patients showed that after one year, significantly fewer relapses (27%) had occurred with medication than with placebo (64%). With regard to the term “compliance”, which is also used here, it should be said that the term “adherence” is increasingly favored. WHO defines “adherence” as the extent to which a person’s behavior-taking a medication, following a diet, making lifestyle changes-is consistent with previously agreed-upon recommendations from a health care provider, emphasizing the patient’s agreement with the recommendations as the main difference in “adherence” versus just “compliance.” Some authors also refer to “concordance” to emphasize the importance of shared decision making regarding therapeutic interventions [9].

Depot medication

Irregular use of an oral antipsychotic medication increases the risk of relapse, with even a short medication break of one to ten days leading to a doubling of the rehospitalization rate [10]. The recommended long-term medication can be ensured particularly well by means of a depot medication with regard to the safety of intake. Depot administration effectively prevents the occurrence of medication breaks, and the active ingredient is reliably released over a longer period of time. In Switzerland in particular, the administration of depot medication still plays a rather minor role. However, parenteral depot preparations with injection intervals of between one and four weeks now exist.

Due to the better bioavailability of the depot medication (no “first pass effect”), a lower dosage is possible compared to oral medication. Also, more consistent plasma levels generally provided fewer side effects than with oral treatment with the same agent [11], but the data on this are inconsistent [12, 13]. A possible disadvantage of depot medication is that it is less controllable (dose changes only take effect with a significant delay, overdoses due to accumulation can occur). There may also be occasional pain and skin reactions at the injection site.

Leucht et al. conclude in a meta-analysis [14] of ten studies from 1975 to 2010 that treatment with depot neuroleptics has a lower relapse rate compared with oral treatment.

Atypical versus typical depot preparations

Depot preparations of atypical antipsychotics have the advantage over typical depot neuroleptics of a lower rate of extrapyramidal motor side effects and, arguably, a lower risk for the occurrence of tardive dyskinesia. For the olanzapine depot, attention should be drawn to the risk of postinjection syndrome, which requires adherence to postinjection monitoring measures.

Indications of depot medication and advice

The S3 treatment guideline for schizophrenia considers depot treatment to be indicated when regular oral medication cannot be ensured and is required at the same time, e.g., due to severe danger to self or others. It is also indicated if the patient prefers this type of medication. However, this is countered by the fact that many patients are not even informed about the possibility of depot medication by their healthcare providers [15, 16]. A patient survey revealed that the proportion of patients who reported general acceptance of depot medication was significantly higher than the proportion of those patients who were on depot medication [17]. It can be concluded from this that the rate of depot medication is likely to increase simply by providing appropriate education about it.

Whether depot medication is generally more beneficial than oral medication because of increased adherence is unclear based on current studies. For example, a recent cohort study showed that compared with oral risperidone medication, not only risperidone depot but also oral clozapine as well as oral olanzapine medication were associated with significantly lower rehospitalization rates [18].

Polypharmacy/combination therapies

Although the evidence favors monotherapies, many patients with chronic mental disorders are often found on extensive medication combinations.

This is especially true for patients with severe and prolonged illnesses. The “European College of Neuropsychopharmacology” (ECNP) recommends the following in a consensus paper regarding antipsychotic combinations:

- Combinations should be given only when monotherapy is only partially effective with respect to the core symptom.

- Combinations are to be given only when monotherapy has been effective with respect to some concomitant symptoms but not others, and therefore additional medication is considered necessary.

- A particular combination could be indicated de novo for individual indications.

- The combination could improve tolerability if two preparations can be given below the respective individual side effect threshold [19].

Especially in long-term therapy, polypharmacy nevertheless seems to be the rule rather than the exception, although there is basically no robust evidence for a polypharmaceutical treatment regime. If, under the above-mentioned conditions, polypharmacy nevertheless appears to be indicated in individual cases, this should be done taking into account possible interactions and enzyme inductions. Electronic aids and also the well-established tables of the Compendium of Psychiatric Pharmacotherapy are available to help avoid these [20].

Side effects and control examinations

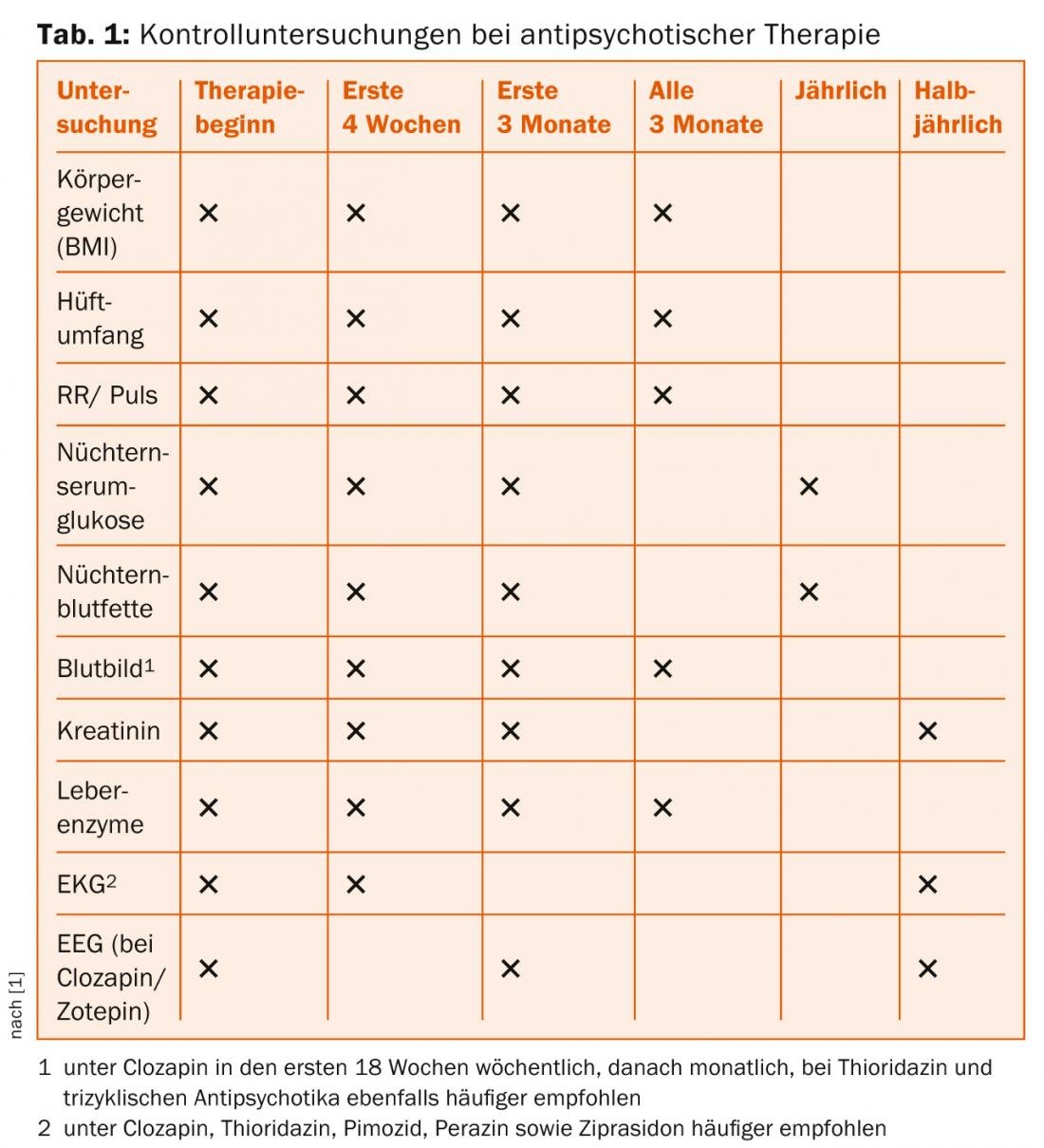

The patient and his caregivers must be informed about side effects and their symptoms. This education should be well documented. These include extrapyramidal motor disorders (EPS), early and tardive dyskinesias, malignant neuroleptic syndrome, and cardiac and metabolic changes such as antipsychotic-induced weight gain, diabetes, and lipid metabolism disorders. This clarification should, of course, be well documented. Efforts should also be made to identify patients at risk for developing type II diabetes and decreased glucose tolerance from the outset: Risk factors include a positive family history of diabetes mellitus, older age, abdominal obesity, certain ethnicities, decreased physical activity, certain eating habits, and pre-existing dyslipidemia [1]. The S3 guideline recommends regular check-ups (Table 1).

PD Wolfram Kawohl, MD

Literature:

- German Society for Psychiatry, Psychotherapy and Neurology (DGPPN) (ed.): Behandlungsleitlinie Schizophrenie. Darmstadt: Steinkopf 2006.

- Deegan PE, Drake RE: Shared decision making and medication management in the recovery process. Psychiatric Services 2006; 57: 1636-1639.

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence: Schizophrenia: Core Interventions in the Treatment and Management of Schizophrenia in Primary and Secondary Care. Guideline 82. London: NICE 2009.

- Quirk A: Obstacles to shared decision-making in psychiatric practice: findings from three observational studies. PhD thesis. Uxbridge, Brunel University 2008.

- Cramer JA, Rosenheck R: Compliance with medication regimens for mental and physical disorders. Psychiatric Services 1998; 49: 196-201.

- Shepherd M, et al: The natural history of schizophrenia: a five-year follow-up study of outcome and prediction in a representative sample of schizophrenics. Psychological Medicine Monograph Supplement 1989; 15: 1-46.

- Gilbert PL, et al: Neuroleptic withdrawal in schizophrenic patients. A review of the literature. Archives of General Psychiatry 1995; 52: 173-188.

- Leucht S, et al: Antipsychotic drugs versus placebo for relapse prevention in schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2012; 379: 2063-2071.

- De las Cuevas C: Towards a clarification of terminology in medicine taking behavior: compliance, adherence and concordance are related although different terms with different uses. Current Clinical Pharmacology 2011; 6: 74-77.

- Weiden PJ, et al: Partial compliance and risk of rehospitalization among California Medicaid patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services 2004; 55: 886-891.

- Lambert M, et al: Pharmacotherapy of schizophrenia (ICD-10 F2) In: Vorderholzer U, Hohagen F (eds): Therapie psychischer Erkrankungen. Munich, Jena: Urban and Fischer 2011; 47-85.

- Adams CE, et al: Systematic meta-review of depot antipsychotic drugs for people with schizophrenia. British Journal of Psychiatry 2001; 179: 290-299.

- Taylor D: Psychopharmacology and adverse effects of antipsychotic long-acting injections: a review. British Journal of Psychiatry Supplement 2009; 52: 13-9.

- Leucht C, et al: Oral versus depot antipsychotic drugs for schizophrenia–a critical systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised long-term trials. Schizophrenia Research 2011; 127: 83-92.

- Heres S, et al: Attitudes of psychiatrists toward antipsychotic depot medication. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 2006; 67: 1948-1953.

- Jäger M, Rössler W:Attitudes toward long-acting depot antipsychotics: a survey of patients, relatives and psychiatrists. Psychiatry Research 2010; 175: 58-62.

- Heres S, et al: The attitude of patients toward antipsychotic depot treatment. International Clinical Psychopharmacology 2007; 22: 275-282.

- Tiihonen J, et al: A nationwide cohort study of oral and depot antipsychotics after first hospitalization for schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry 2011; 168: 603-609.

- Goodwin G, et al:Advantages and disadvantages of combination treatment with antipsychotics ECNP Consensus Meeting, March 2008, Nice. European Neuropsychopharmacology 2009; 19: 520-532.

- Benkert O, Hippius H: Compendium of psychiatric pharmacotherapy. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer 2011.

- Quirk A, et al: How pressure is applied in shared decisions about antipsychotic medication: a conversation analytic study of psychiatric outpatient consultations. Sociology of Health & Illness 2012; 34: 95-113.

InFo Neurology & Psychiatry 2014; 12(1): 8-10.