The volume of prescriptions for psychotropic drugs is rising rapidly in many segments. The prescription of psychotropic drugs is therefore part of everyday life, not only in psychiatric practice but also in the practice of general practitioners. What do you need to consider?

Prescribing psychotropic drugs is part of everyday life not only in psychiatric practice, but also in family practice. Clearly psychological conditions such as depression, anxiety disorders or schizophrenia can be addressed, but pain disorders, sleep disorders or other diseases from the psychosomatic spectrum are also treated with substances from this group. In 2017, drugs for central nervous system disorders had the largest market share of all drugs sold in Switzerland, at 16.3%, according to Interpharma [1].

The volume of prescriptions for psychotropic drugs is rising rapidly in many segments: for example, prescriptions for antidepressants have increased by more than 40% in the last ten years. In this context, the prescription of SSRIs (dual) and SNRIs (triple) is booming, while the prescription of older antidepressants such as tricyclics or MAO inhibitors is declining. Among antipsychotics, atypicals in particular are prescribed more frequently (>60%), while high-potency typicals have declined slightly. Prescriptions of psychostimulants are roughly constant and those of tranquilizers are declining. Approximately one-third of all psychotropic drug prescriptions come from general practitioners [2].

The general practitioner plays a key role in psychopharmacotherapy, as he or she knows the patient best in terms of the totality of his or her physical and mental suffering, can identify contraindications to medication such as impaired renal function, and can keep track of possible interactions in the case of polymedication. He is also often the first point of contact when his patient suffers from burnout, concentration disorders or dementia. The inhibition threshold for a consultation with the family doctor is usually much lower for patients than that for a visit to the psychiatrist. The differential diagnostic differentiation from physical ailments also occurs here, since many somatic diseases are associated with a high prevalence of comorbid depressive disorders. For example, up to 27% of patients with cardiovascular disease and up to 75% of patients with Parkinson’s disease show signs of depression [3,4]. Finally, many medications used in somatics, such as steroids or beta-blockers, also cause the frequent adverse effect of depression, which should be taken into account when using them.

Many psychotropic drugs require monitoring of metabolizing or excreting organs: ECG checks for substances potentially prolonging QTc time, hematological examinations, e.g., when taking clozapine, weight checks and examinations for metabolic syndrome among many antipsychotics, or therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) for substances with a narrow therapeutic range, such as lithium. As a rule, these examinations are performed in the general practitioner’s office. Numerous treatment recommendations and internal hospital directives have been published on meaningful control examinations under psychopharmacotherapy.

Antidepressants

Mental illness represents a significant – and growing – proportion of the world’s disease burden. The point prevalence of the working population of having a mental illness at any one time is 20%. For depression alone, the 12-month population prevalence in Europe is 7.9%. The need for antidepressants is increasing in the 33 OECD countries. At the same time, suicide rates are declining here, which has been attributed to destigmatization of mental illness, better coverage of care, and increased attention to affective disorders [5]. According to the WHO, approximately 350 million people worldwide suffer from depression, and suicide kills over 800,000 people per year. Socioeconomic follow-up costs of depressive disorders are immense: in the USA, these were estimated at 210 billion in 2015 [6]. Guideline-based treatment for depression can be found in treatment recommendations from national professional societies. It depends on the respective severity of the disease (mild, moderate, severe), the accompanying symptoms and the individual disease history [7–10].

Scores such as Hamilton or Beck Depression Inventory can be used to quantify disease severity [11,12]. Severe depression that causes a complete loss of function in daily life or is characterized by suicidality should be treated as an inpatient.

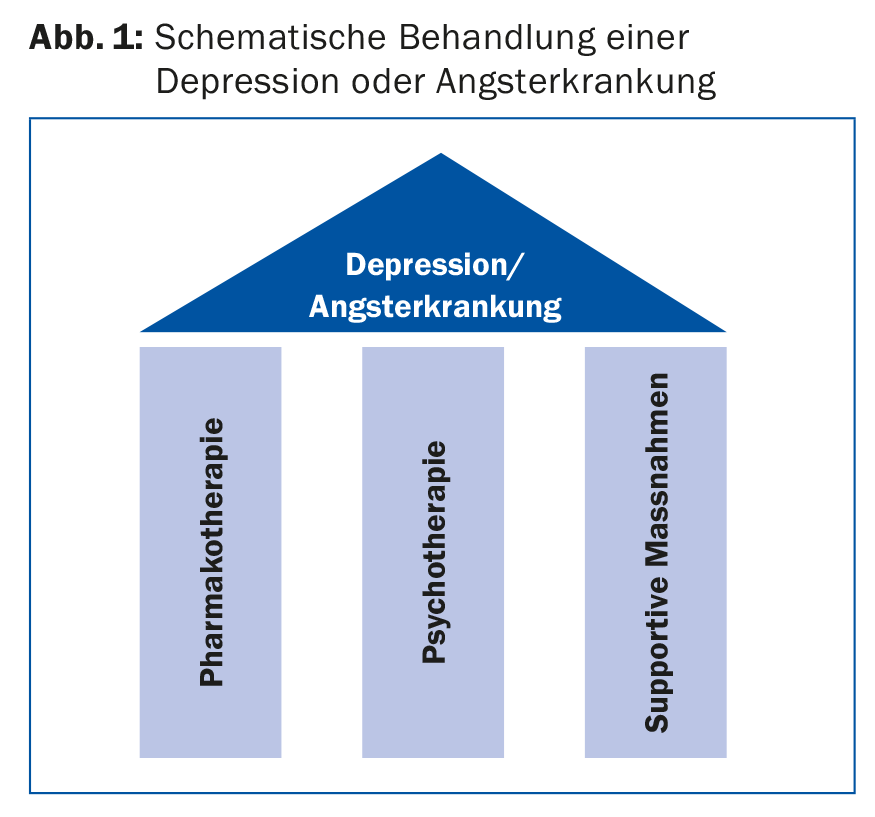

For antidepressants, the more severe the depression, the more likely the benefit of pharmacotherapy. In very simplified terms, one could say that mild depression should not be treated, moderate depression can be treated, and severe depression should definitely be treated pharmacologically. Pharmacotherapy is always part of a long-term overall clinical concept that takes biographical, social, somatic and psychological backgrounds into account. Successful depression treatment rests on three pillars: psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy and supportive measures (Fig. 1) . The latter include exercise, light therapy, and, if necessary, stimulation or relaxation techniques. Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) may be used when the disease is severe. This concept must be communicated to the patient. For optimal compliance with pharmacotherapy, it should be noted that many adverse effects (ADEs), such as headache, nausea, or dizziness, usually occur with antidepressants immediately after treatment initiation and usually remit rapidly, but the desired effects do not occur until approximately 14 days after treatment initiation.

Antidepressants used include as main representatives the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI), the more potent selective serotonin/norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SSNRI), the tricyclic antidepressants, reboxetine as a selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI), moclobemide as a reversible MAO-A inhibitor (RIMA), bupropion as a selective norepinephrine/dopamine reuptake inhibitor (SNDRI), and agomelatine, a melatonin 1/2 receptor agonist as well as 5-HT-2C antagonist. A new addition is vortioxetine, which acts primarily by inhibiting the serotonin (5 HT) transporter. Furthermore, we have the second-generation antidepressants mianserin and trazodone. Ketamine as an NMDA antagonist is used “off label” for acute treatment of major depression.

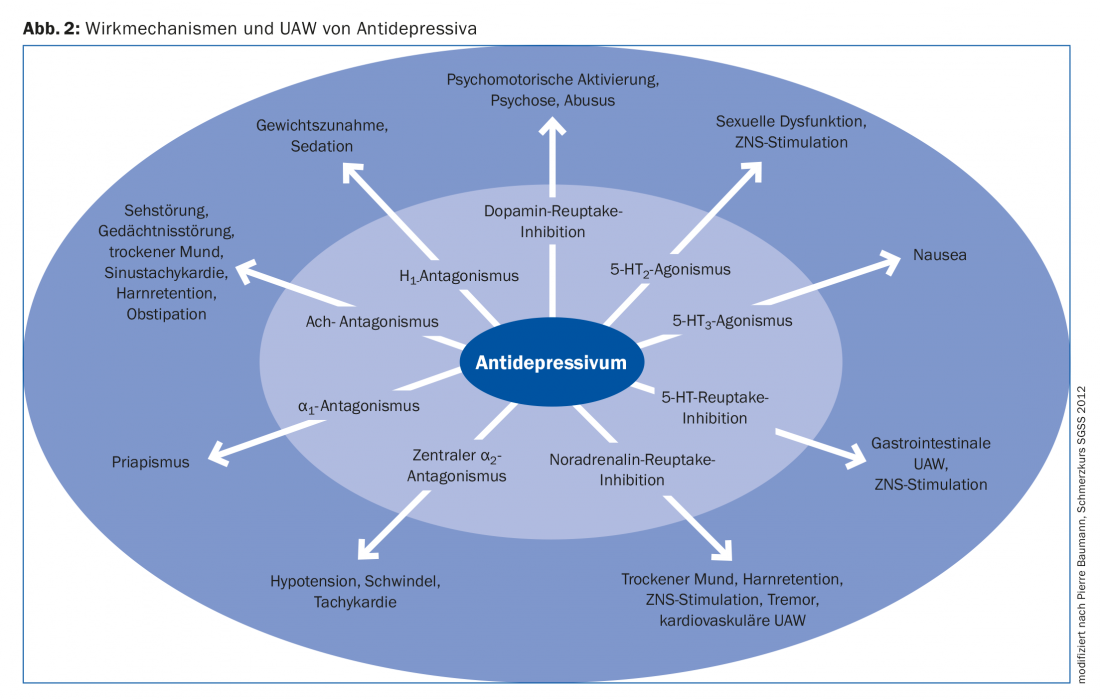

The choice of antidepressant is made according to the individual patient’s medical history, the respective accompanying symptoms of depression and the physician’s experience. Precise knowledge of the mechanism of action of the respective substance can be helpful here: Depending on the system addressed, the drug’s spectrum of action can be estimated and possible adverse effects can be anticipated (Fig. 2). For example, a depressed patient with insomnia is more likely to be prescribed trazodone, amitriptyline, or mirtazapine as a concomitant sleep-inducing medication; an obese patient is more likely not to be given mirtazapine because significant weight gain is common among them; and an elderly patient is more likely not to be selected for an anticholinergic tricyclic.

Is antidepressant administration useful?

Despite high prescription frequency and many years of clinical experience of their efficacy, the use of antidepressants is always questioned. Critical voices questioning the efficacy of antidepressants altogether and attributing it to methodological errors in the conduct of studies were raised about ten years ago [13].

A new meta-analysis of the efficacy of 21 antidepressants, which looked at 116,477 depressed patients in 522 clinical trials, showed that antidepressant treatment is clearly superior to placebo. Primary endpoints here were “efficacy” (response rates of patients with >50% reduction on a depression scale) and “acceptability” (measured by the proportion of patients who discontinued treatment). Secondary endpoints were depression score after treatment, remission rate, and dropout due to UAW. The meta-analysis also takes into account numerous individual comparisons of active substances with each other. Regarding “efficacy,” amitriptyline was most effective with an OR of 2.13 (95% CI 1.89-2.41) vs. placebo, followed by mirtazapine and SNRI. In single comparisons, agomelatine, amitriptyline, escitalopram, mirtazapine, paroxetine, venlafaxine, and vortioxetine were more effective than other antidepressants (ORs 1.19-1.96). In terms of acceptability, not surprisingly, agomelatine, citalopram, escitalopram, fluoxetine, sertraline, and vortioxetine were superior to other agents. Tricyclics showed the highest treatment discontinuation rates [14].

Antidepressants in pain therapy

Psychotropic drugs also have a firm place in somatic medicine. Neuropathic pain affects approximately 8% of the population. The treatment is often demanding, happens multimodal and interdisciplinary. Therapeutic, pharmacological and interventional techniques are used. First-line pharmacologic agents for the treatment of neuropathic pain are antidepressants and antiepileptic drugs. For example, the tricyclic antidepressants amitriptyline, clomipramine, imipramine and trimipramine are also approved in Switzerland for the indication “chronic pain conditions”. Pathophysiologically, this makes sense, as these substances can influence spinal activity and thus pain processing in top-down modulation of descending efferents [15]. Thus, amitriptyline is the substance with the lowest Number Needed to Treat (NNT) in peripheral neuropathic pain, ahead of antiepileptic drugs, opioids, and gabapentin [16]. Furthermore, there is a large intersection between depression and pain: for example, 25% of all patients with chronic pain are diagnosed with depression, and pain syndromes conversely occur in >50% of depressed patients. The administration of antidepressants in multimodal pain therapy is therefore reasonable and well established.

Anxiolytics and sedatives

Substances of different groups are used as sedatives. These classically include benzodiazepines, narcotics and barbiturates, but also antipsychotics, sedative antidepressants, opioids, antihistamines, clonidine and herbal agents. Depending on the clinical context, these substances can be used judiciously as long as potentially dangerous adverse drug effects or interactions and possible development of dependence are considered. Rationally, benzodiazepines are used selectively for anxiety and panic disorders or acute chest pain. Benzodiazepines have anxiolytic effects, increase CNS GABA concentrations, decrease peripheral catecholamine plasma levels, cause acute coronary vasodilation, and have prophylactic effects against arrhythmias. Thus, they are also pathophysiologically useful in the acute treatment of myocardial infarction. Long-term use, such as in chronic sleep disorders, does not appear to be useful.

Psychostimulants and neuroenhancers

The use of psychostimulants, primarily methylphenidate but also lisdexamphetamine, is widespread and increasing. ADHD affects 3-5% of Swiss children and adolescents. Of these, a quarter are treated with methylphenidate. However, the doctor is not only consulted for medical indications, but also because patients increasingly feel unable to cope with the high demands of their working environment. Approximately 4% of employed persons or persons in education in Switzerland have already taken prescription drugs for mood enhancement or cognitive performance enhancement (neuroenhancement) without medical indication. Among students, 7.6% have already taken performance-enhancing prescription drugs, including methylphenidate in 4.1% of respondents. Whether taking performance-enhancing substances makes sense or not, prescribers are increasingly confronted with these questions [17,18].

Antipsychotics

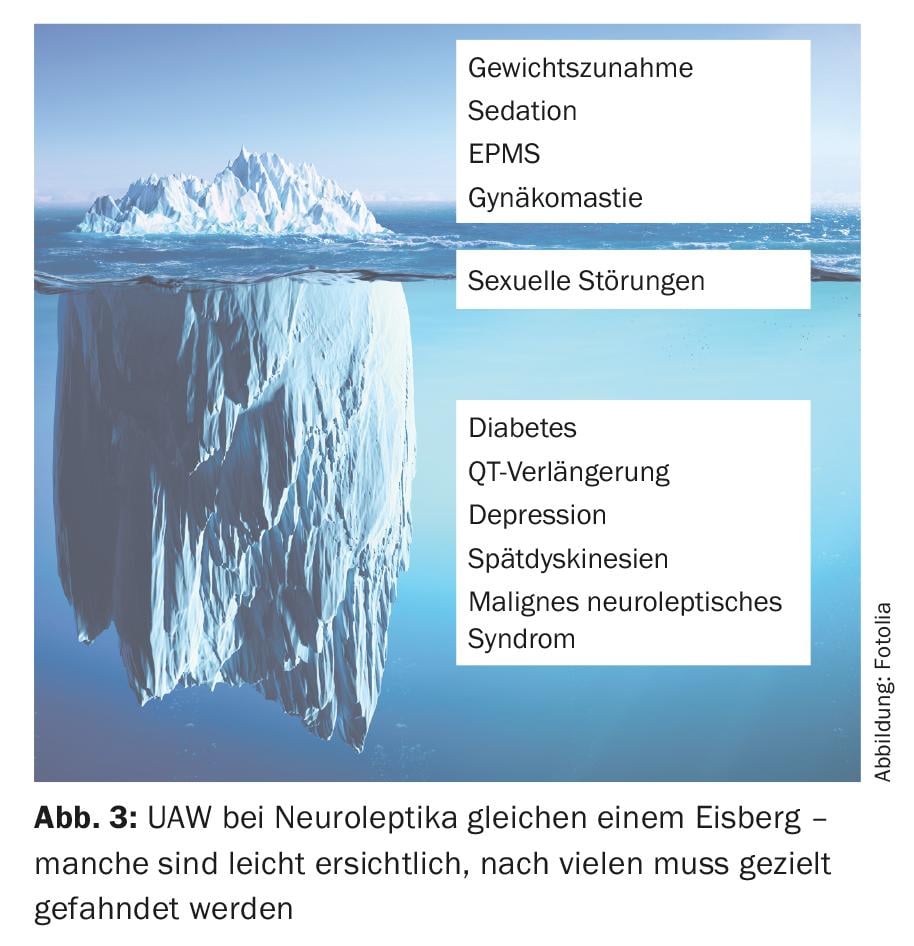

The effects of antipsychotics include antipsychotic, sedative, extrapyramidal-motor, endocrine, cardiac, and metabolic properties. Different receptor affinities exist between the individual substances, which determine the desired and undesired effect profile. Indications include schizophrenia and manic psychosis, and the substances are also used for psychomotor agitation, in anesthesia, and as antiemetics. Pharmacotherapy is the cornerstone of acute and long-term treatment of schizophrenic disorders. It leads to remission in 17-78% of first-episode patients. In relapses, between 16% and 62% of patients still respond, depending on the study, but higher doses are needed to achieve remission and remission is achieved only after a longer period of time. The complexity of treating patients with schizophrenic disorders has greatly increased. The form of application, dose and also combination therapies depend on the stage of the disease (initial psychosis, relapse), the severity of the disease and the symptom expression (positive/negative symptoms) as well as the ADRs. In the acute stage, combination therapy with benzodiazepines is often indicated. Guideline-based therapy is usually in the hands of the psychiatrist and can be found at professional societies (e.g., SGPP, DGPPN, WFSBP). The general practitioner is usually closely involved in the monitoring of the patient on antipsychotic therapy, as this potent group of substances shows numerous, often severe potential ADRs that should be closely monitored, as they are not always obvious (Fig. 3).

Special case: antipsychotic therapy in geriatric patients.

In geriatric pharmacotherapy, antipsychotics are often used for sedation or even as sleep medication. Over 60% of dementia patients in nursing homes receive at least one psychotropic drug, primarily antipsychotics. Evidence of increased morbidity and mortality from cardiovascular events, falls, pneumonia, ischemic insult, among others, emerged. The risk of mortality is increased by a factor of 1.5 to 1.7 in this patient population, resulting in a “black box warning” from the FDA. The indication “dementia” was deleted for antipsychotics . The benefits and risks of prescribing antipsychotics should be considered particularly carefully in older age [19–21].

Take-Home Messages

- Psychopharmacotherapy is often indicated and is effective and useful not only for mental illness.

- A relevant proportion of all psychotropic drugs are prescribed in general internal medicine practice. Adverse drug reactions are also monitored here.

- Interdisciplinary cooperation between general internists and psychiatric specialists ensures the greatest possible safety for the patient.

Literature:

- Interpharma: Pharma Market Switzerland. Association of Research-Based Pharmaceutical Companies in Switzerland. Basel 2018.

- Schwabe U, et al. (Ed.): Arzneiverordnungs-Report 2017. Springer 2017.

- Rudisch B, Nemeroff C: Epidemiology of comorbid coronary artery disease and depression. Biol Psychiatry 2003 Aug 1; 54(3): 227-240.

- McDonald WM, et al: Prevalence, etiology, and treatment of depression in Parkinson’s disease. Biol Psychiatry 2003 Aug 1; 54(3): 363-375.

- OECD: Health at a Glance 2017: OECD Indicators. OECD Publishing 2017.

- WHO: Preventing suicide: A global imperative. WHO 2014.

- Holsboer-Trachsler E, et al: The somatic treatment of unipolar depressive disorders: Update 2016. Swiss Medical Forum 2016; 16(35): 716-724.

- NICE guidelines: Depression in adults: recognition and management. April 2018

- German Society for Psychiatry, Psychotherapy and Neurology (DGPPN): S3-Leitlinie/Nationale Versorgungsleitlinie: Unipolare Depression. 2017.

- American Psychiatric Association: Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Major Depressive Disorder. 3rd ed. 2010.

- Hamilton M: A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1960; 23: 56-62.

- Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M: An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1961; 4: 561-571.

- Ioannidis JP: Effectiveness of antidepressants: an evidence myth constructed from a thousand randomized trials? Philos Ethics Humanit Med 2008 May 27; 3: 14.

- Cipriani A, et al: Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet 2018 Apr 7; 391(10128): 1357-1366.

- Gilron I, et al: Combination pharmacotherapy for management of chronic pain: from bench to bedside. Lancet Neurol 2013 Nov; 12(11): 1084-1095.

- Finnerup NB, et al: Algorithm for neuropathic pain treatment: an evidence based proposal. Pain 2005 Dec 5; 118(3): 289-305.

- BAG: Performance-enhancing drugs in the context of neuroenhancement and on the subject of the therapeutic use of drugs containing methylphenidate. 2014.

- Eckhard A: Performance-enhancing drugs, meaning, use and effects. Expert report for the attention of the FOPH. May 20, 2014.

- Steinberg M, Lyketsos CG: Atypical antipsychotic use in patients with dementia: managing safety concerns. Am J Psychiatry 2012 Sep; 169(9): 900-906.

- Danielsson B, et al: Antidepressants and antipsychotics classified with torsades de pointes arrhythmia risk and mortality in older adults – a Swedish nationwide study. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2016 Apr; 81(4): 773-783.

- Gerhard T, et al: Comparative mortality risks of antipsychotic medications in community-dwelling older adults. Br J Psychiatry 2014 Jul; 205(1): 44-51.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2018; 13(9): 12-17