The indication for endovascular revascularization is an essential component for therapeutic success. There are immense technical possibilities for modern endovascular revascularization. Often, academic reappraisal of clinical efficacy and cost-effectiveness lags well behind the pace of innovation. Vascular medicine must be understood in an interdisciplinary manner; only in this way can the strengths of different revascularization techniques be exploited for the benefit of the patient.

The prevalence of peripheral arterial disease (PAVD) is increasing – a trend that will continue due to demographic developments [1]. Both the vascular specialist and the primary care physician are challenged to treat this common condition sensibly, efficiently, and appropriately. Interventional therapy is an important cornerstone in this context, the essential building block of which is the indication for successful treatment. This should always pursue a clearly predefined goal according to the individual needs of each patient.

However, noninterventional conservative therapy for PAVD is no less important, perhaps even more significant, because of its profound impact on the patient’s overall prognosis. In the vast majority of cases, PAVK is caused by arteriosclerosis. This is a systemic condition with often further clinical manifestations in other arterial flow areas; of these, the peripheral arterial manifestation is the least vital threatening. Most PAVK patients have coronary artery disease and cerebral atherosclerosis [2]. For this reason, patients must be recommended a healthy lifestyle without nicotine and with plenty of exercise, and secondary prophylaxis must be given with medication. Statin therapy and platelet aggregation inhibition are the cornerstones of drug therapy. The other cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension and diabetes must be controlled as well as possible. In the experience of the authors, this realization has fortunately now reached most GP and specialist colleagues. The practical implementation alone is difficult; patient compliance is required here. Especially at an advanced age it is difficult to start a “healthy life” if one was not used to such a life before.

Indications for interventional treatment

PAVK, based on atherosclerosis, is not curable. A palliative situation exists and a strict indication for interventional revascularization is usually only given when amputation is imminent. In this case, the patient has either an ischemic-related and/or nonhealing lesion due to ischemia, or ischemic-related rest pain and deficits. These purely clinical criteria are metrologically supported with ABI measurement and oscillography.

The indication is less stringent when progression of PAVK to impending critical ischemia is seen. Here, the data situation is not clear. However, diabetics are particularly affected and need to be treated more aggressively because of their significantly increased risk [3]. Intermittent claudication is not a strict indication for interventional treatment. In this case, many aspects must be considered to determine whether percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (PTA) is appropriate. On the one hand, it must be considered whether the conservative treatment options have been exhausted and how limiting the disease is for the patient; on the other hand, the morphology of the lesion plays an important role. Furthermore, the existing comorbidities should be put in relation to PAVK.

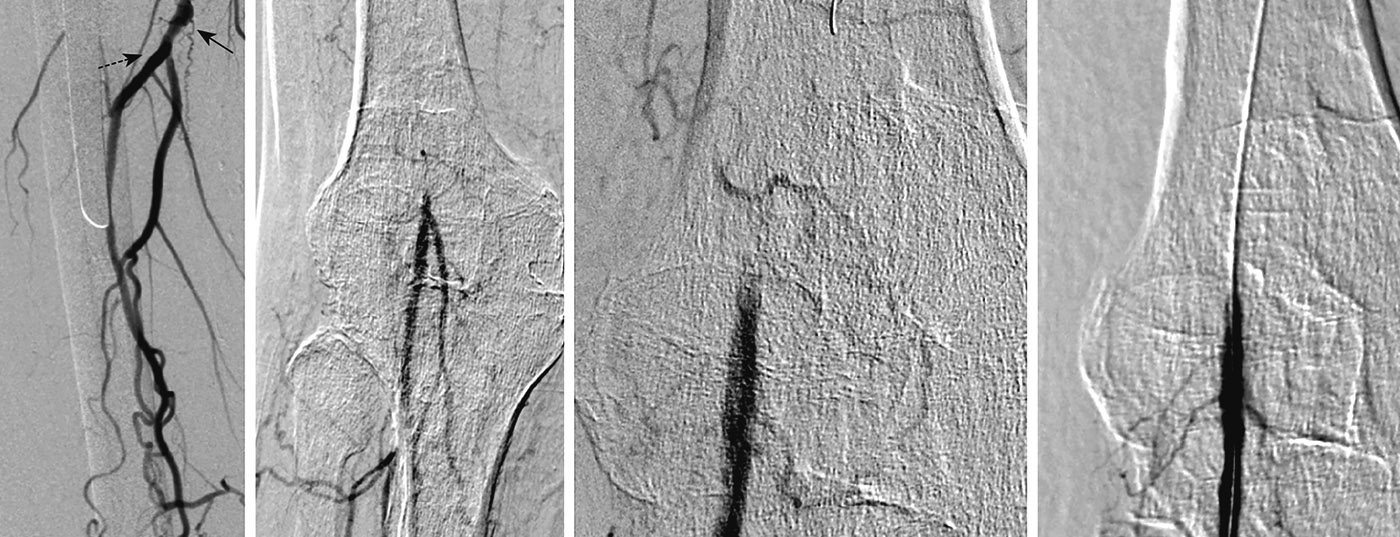

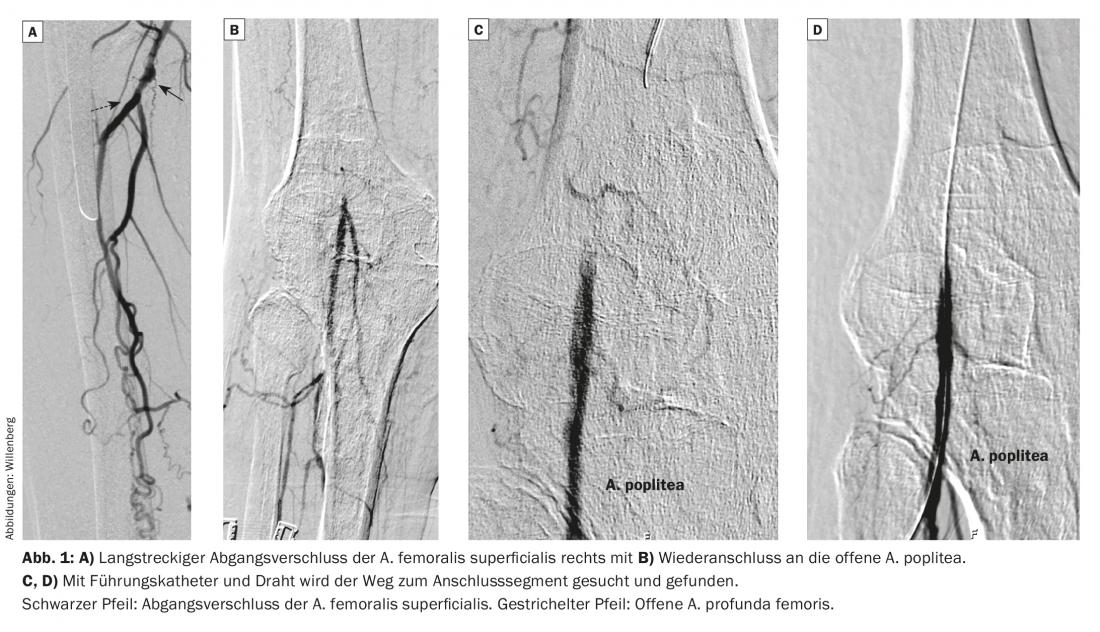

In general, the length of a lesion negatively correlates with the sustainability of successful interventional treatment. Longer-stretch occlusion (>5 cm), e.g. of the superficial femoral artery, has a not insignificant recurrence probability of up to 40% within the first twelve months after interventional treatment, which is often not without effort. Recurrent procedures are each more prone to complications and do not necessarily show a more sustainable result. The primary care physician and specialist are required to put all aspects together to choose the individual treatment strategy for each patient.

Interventional approach

For the planning of the intervention, the most important thing is from where the access takes place. Femoral antegrade, retrograde, and brachial approaches are most common. Increasingly, alternative approaches are used in patients with severe circulatory disorders, such as puncture of the arteries of the lower leg or foot. Access should always be as close as possible to the lesion to be treated or provide the opportunity to treat multiple lesions simultaneously. The clarifying duplex sonography is used for precise planning of the procedure. However, catheter options are now so diverse that lesions far from the access site can be treated, such as lesions in the leg with access via the brachial artery. The smaller the access is chosen, the lower the risk of puncture-related complications [4]. Here, too, it is now very often possible to work with small accesses (4 French, 1.33 mm outer diameter of the lock) due to the technical development of the material.

Balloon or stent or both – with or without drug coating?

The development of interventional technology has been rapid in recent years. Only rarely has clear scientific evidence been able to keep pace. Nevertheless, minimally invasive endovascular treatment is now the first choice over surgical revascularization for most indications. The question of whether PTA alone is sufficient or whether additional stenting is necessary is not infrequently decided intuitively by the interventionalist; hard criteria hardly exist. A good angiographic result with strong flow and clinically improved peripheral pulse currently justifies in our view the omission of a stent in the vast majority of cases. Flow-limiting dissection of the vessel, on the other hand, suggests the additional use of a stent.

Aorto-iliac lesions show promising success rates with PTA, both with PTA alone and with the use of stents. The situation is much more complicated in femoro-popliteal lesions (Fig. 1). These have very high recurrence rates of up to 40% within the first twelve months. However, it appears that the use of paclitaxel-coated nitinol stents can significantly reduce these recurrence rates [5]. Meanwhile, those who believe that the foreign material of the stent has a negative impact on the arterial intima can also use a balloon coated with drugs. Recent data support its use in the femoro-popliteal segment, especially for short-stretch lesions [6]. Drug-eluting balloons are commonly used, especially in the treatment of recurrences, such as neointimal instent stenosis.

In the future, bioresorbable stents will also be discussed. Initial studies of these devices, which dissolve within months, are already underway. In addition, the so-called thrombectomy catheters should be mentioned, which can remove older plaque material as well as fresh thrombi. These catheters are most suitable for the pelvic arterial circulation or the femoro-popliteal segment. As with a “vacuum cleaner”, which additionally mobilizes thrombotic wall material, one goes with it through the lesion and aspirates the fresh and older obstructing material.

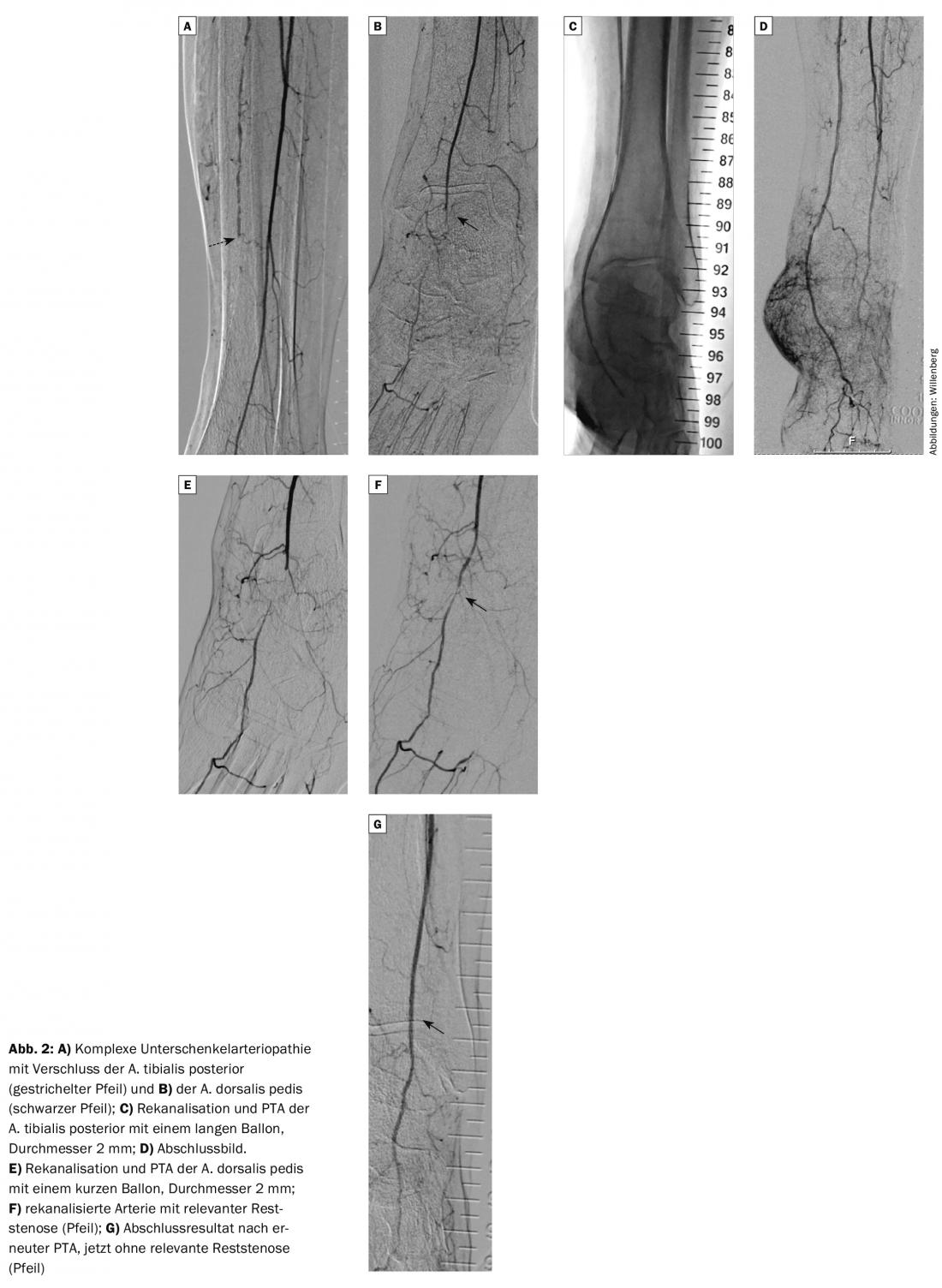

Even more difficult, because often also clinically more delicate, is the situation with the arteries of the lower leg and foot. These should be approached only with strict indication of critical ischemia by very experienced interventionalists. Technical advances in the material now make it possible to perform completely distal catheter interventions down to the arteries of the foot. Very fine wires and balloons are used here (Fig. 2). A now widely known study has shown that the clinical outcome of intervening on the arteries of the lower leg is as sustainable as that after femorocrural bypass surgery [7]. For this reason, intervention is now considered the treatment of choice for lesions of the arteries of the lower leg and foot as well.

Preservation of the surgical therapy option

PTA is an option of revascularization, the advantage of which lies decisively in the faster convalescence and – due to the “tiny” access – the low complication rate. However, it is important to remember that the option for vascular surgical revascularization should ideally not be destroyed, for example, by inserting a stent into a potential connecting segment for bypass. Therefore, it cannot be overemphasized that the angiologist, interventional radiologist, and vascular surgeon must work closely and collegially to find the appropriate treatment strategy for the patient. Modern vascular centers should take this philosophy to heart; they are now also only allowed to use the designation “vascular center” if all the disciplines mentioned are involved and involved.

Literature:

- Hirsch AT, Duval S: The global pandemic of peripheral artery disease. Lancet 2013; 382(9901): 1312-1314. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61576-7.

- Dormandy J, Heeck L, Vig S: Lower-extremity arteriosclerosis as a reflection of a systemic process: implications for concomitant coronary and carotid disease. Semin Vasc Surg 1999; 12(2): 118-122.

- Willenberg T, et al: An angiographic analysis of atherosclerosis progression in below-the-knee arteries after femoropopliteal angioplasty in claudicants. J Endovasc Ther 2010; 17(1): 39-45. doi:10.1583/09-2819.1.

- Savolainen H, et al: Femoral pseudoaneurysms requiring surgical treatment. Trauma Mon 2011; 16(4): 194-197. doi:10.5812/kowsar.22517464.3186.

- Dake MD, et al: Sustained safety and effectiveness of paclitaxel-eluting stents for femoropopliteal lesions: 2-year follow-up from the zilver PTX randomized and single-arm clinical trials. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013; 61(24): 2417-2427. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2013.03.034.

- Zeller T, et al: Drug-coated balloons in the lower limb. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 2011; 52(2): 235-243.

- Bradbury AW, et al: Bypass versus angioplasty in severe ischaemia of the leg (BASIL): multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2005; 366(9501): 1925-1934. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67704-5.

CARDIOVASC 2015; 14(4): 16-19