Elevated liver values should always be taken seriously and clarified, as only then can the cause be treated and the gradual progression of liver disease prevented. This article provides an overview of current Good Clinical Practice standards.

The condition of our central metabolic organ, the liver, is mapped in every basic laboratory diagnostic and is therefore encountered by physicians on a daily basis. If elevated liver values are detected, however, there is often uncertainty regarding further clarification. The variety of hepatic, biliary and extrahepatic causes is not infrequently contrasted with only mild laboratory elevations and asymptomatic patients. This discourages further diagnostics. However, if left untreated, a chronic inflammatory process can lead to cirrhotic remodeling of the liver and the resulting complications. Clarification of the causes, most of which can be treated or influenced, is therefore the central step in preventing the progression of acute liver disease into chronic liver disease or chronic liver disease into cirrhotic liver disease.

A simple basic diagnosis, which can be performed in any family practice, already allows an efficient first categorization and thus a rational further diagnosis. This procedure will now be presented as an example.

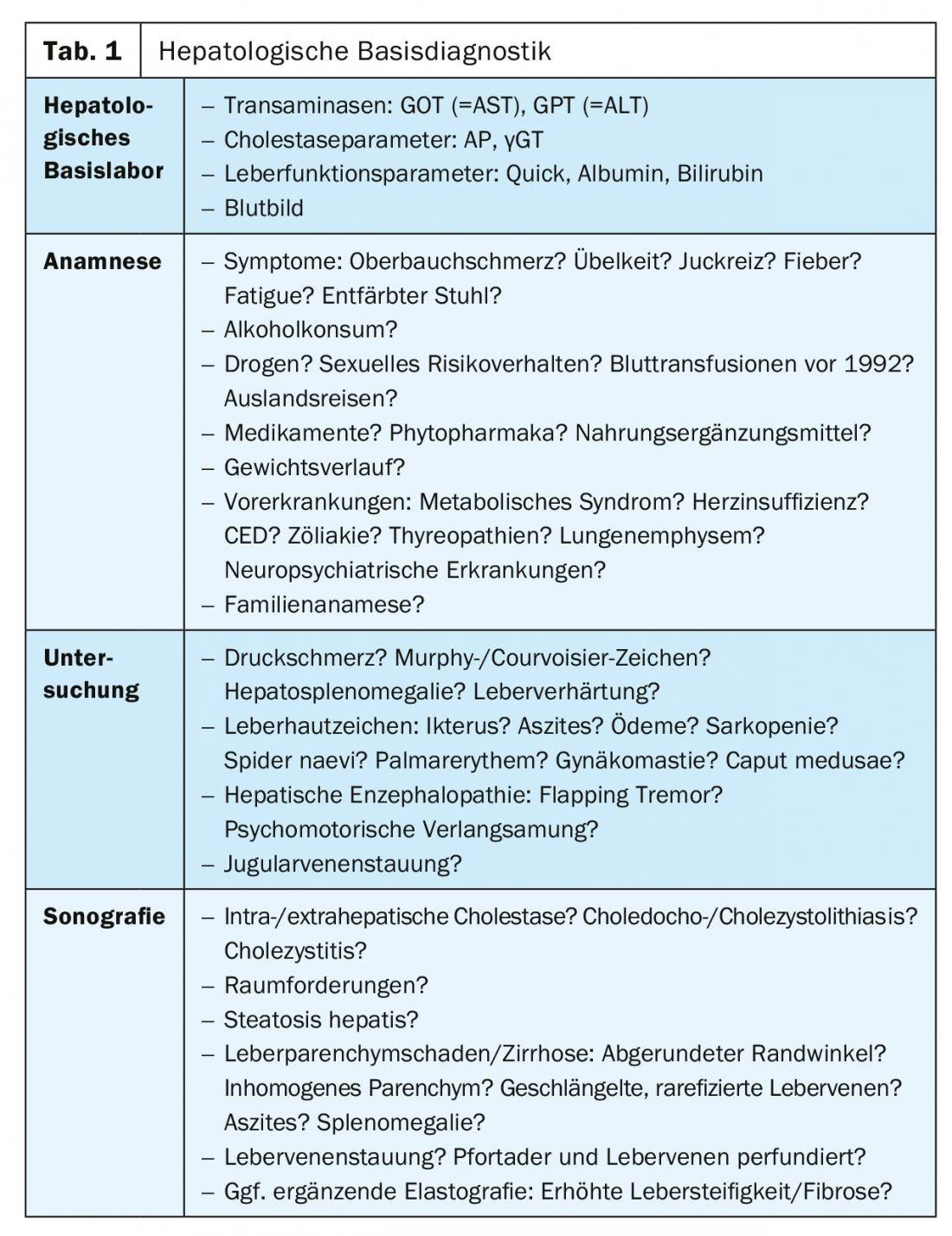

Basic hepatology diagnostics

Every hepatological workup begins with the collection of complete liver enzymes, a medical history, clinical examination, and liver ultrasonography (Table 1). In liver diseases, the history often provides the central clue to the etiology and is therefore considered the most important single examination in the evaluation of elevated liver values. Clinical examination may further reveal stigmata of chronic liver disease such as spider naevi, palmar erythema, etc. Finally, sonography answers the question of the presence of chronic remodeling or cirrhosis. In addition, she clarifies vascular causes such as portal vein thrombosis, diagnoses steatosis or even tumors and, in the case of cholestatic laboratory constellations, decides whether cholestasis is actually present.

Laboratory chemistry distinguishes between values that indicate liver damage and those that provide information about liver function. The latter is represented by the synthesis parameters Quick (INR) and albumin as well as the excretion parameter bilirubin and may be limited in liver cirrhosis but also in acute liver failure.

Acute or chronic hepatobiliary injury may be manifested by elevation of transaminases and cholestasis parameters. The transaminases GOT (=AST) and GPT (=ALT) indicate liver cell inflammation (hepatitis) or necrosis. In most cases, liver-specific GPT is leadingly elevated; whereas in alcohol or other toxic genesis, GOT is typically elevated. Alkaline phosphatase (AP) and gamma-glutamyltransferase (γGT) constitute the cholestasis parameters. Both values must always be considered together, since an isolated increase in AP may also be due to bone diseases and an isolated increase in γGT may even be due to a variety of unspecific causes that do not require further clarification.

Elevation of bilirubin has a special role because it may indicate cholestasis (posthepatic) as well as acute hepatitis or hepatic impairment (intrahepatic). If it occurs in an isolated and leading manner with an indirect component, it is usually due to hemolysis (prehepatic) or Meulengracht’s disease.

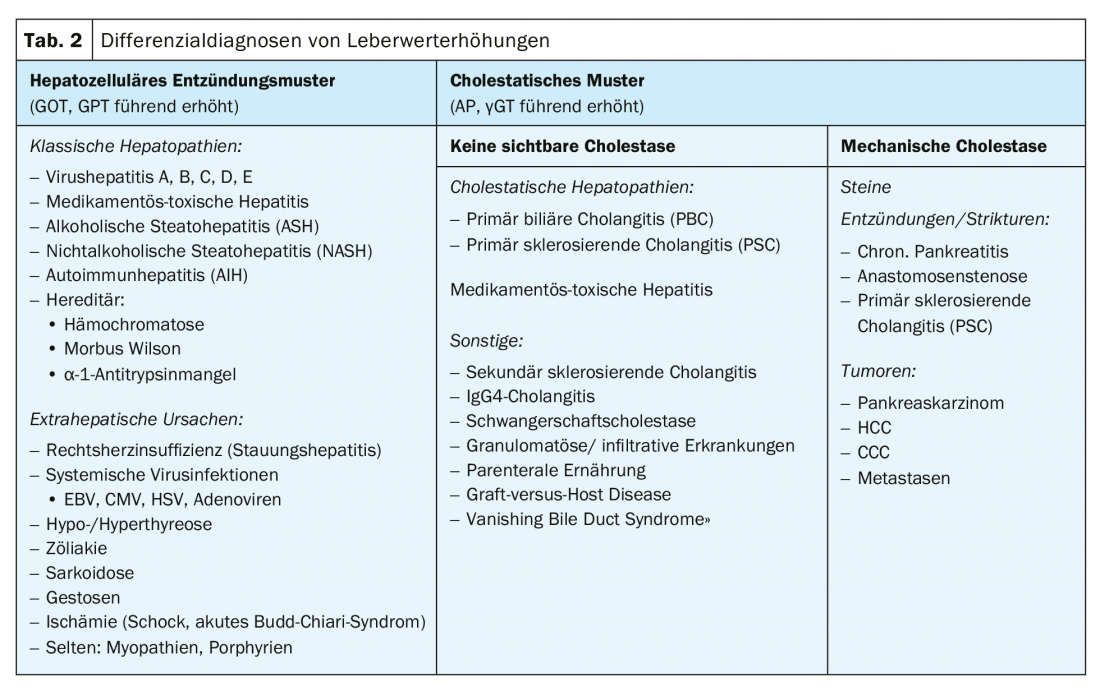

Laboratory chemistry can distinguish a “hepatocellular inflammatory pattern” with leading elevated transaminases from a “cholestatic pattern” with leading elevated cholestasis parameters [1,2]. Different differential diagnoses can be subsumed under both patterns (Table 2). These differential diagnoses can be further subdivided etiologically by sonographic evaluation of the bile ducts. In addition, basic diagnostics allow a statement to be made as to whether an acute, possibly symptomatic disease with values that are often many times higher than the upper norm is present or a chronic, mostly asymptomatic constellation with a mild increase in liver enzymes and whether cirrhosis of the liver and restriction of liver function already exist in this case. The higher the liver values, the broader the differential diagnosis should be from the outset [1].

Case 1: Acute hepatitisA 40-year-old female patient presents with jaundice. Anamnestically, nausea and vomiting have been present for two weeks. It is the first episode of this type; there are no changes in stool or urine colorite. Except for L-thyroxine in Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, no medications or phythotherapeutics are taken. Alcohol: two glasses of wine per week; no drug use; no foreign travel. She works as an educator. Clinical examination reveals a slender patient with icteric skin coloration. There are no other liver skin signs. The abdomen is soft and not painful to the touch. Elevated in the laboratory are: GOT 1731U/l, GPT 2236U/l, AP 165U/l, γGT135U/l, total bilirubin 4.9 mg/dl; normal values are: Quick 110%, albumin 4.0 g/dl. Sonography: Homogeneous, non-steatotic liver parenchyma, acute marginal angle, portal vein progradely perfused, no cholestasis, gallbladder unremarkable. |

Baseline diagnostics in this case reveal acute, symptomatic, and icteric disease with markedly elevated transaminases and no chronic liver parenchymal damage. A cholestatic cause of icterus – although presumable in a 40-year-old symptomatic woman – is not present either sonographically or from the laboratory constellation: There is a “hepatocellular inflammatory pattern”. This constellation can be summarized as acute hepatitis.

In acute hepatitis, attention should always be paid to evidence of a fulminant course with acute liver failure. This is manifested by acute hepatic dysfunction, which is most directly indicated by a drop in the Quick value, with simultaneous occurrence of hepatic encephalopathy. This requires immediate admission to a hepatology center for evaluation of the need for liver transplantation. In the present case, however, with a normal Quick value and a neurologically unremarkable patient, there is no evidence of this.

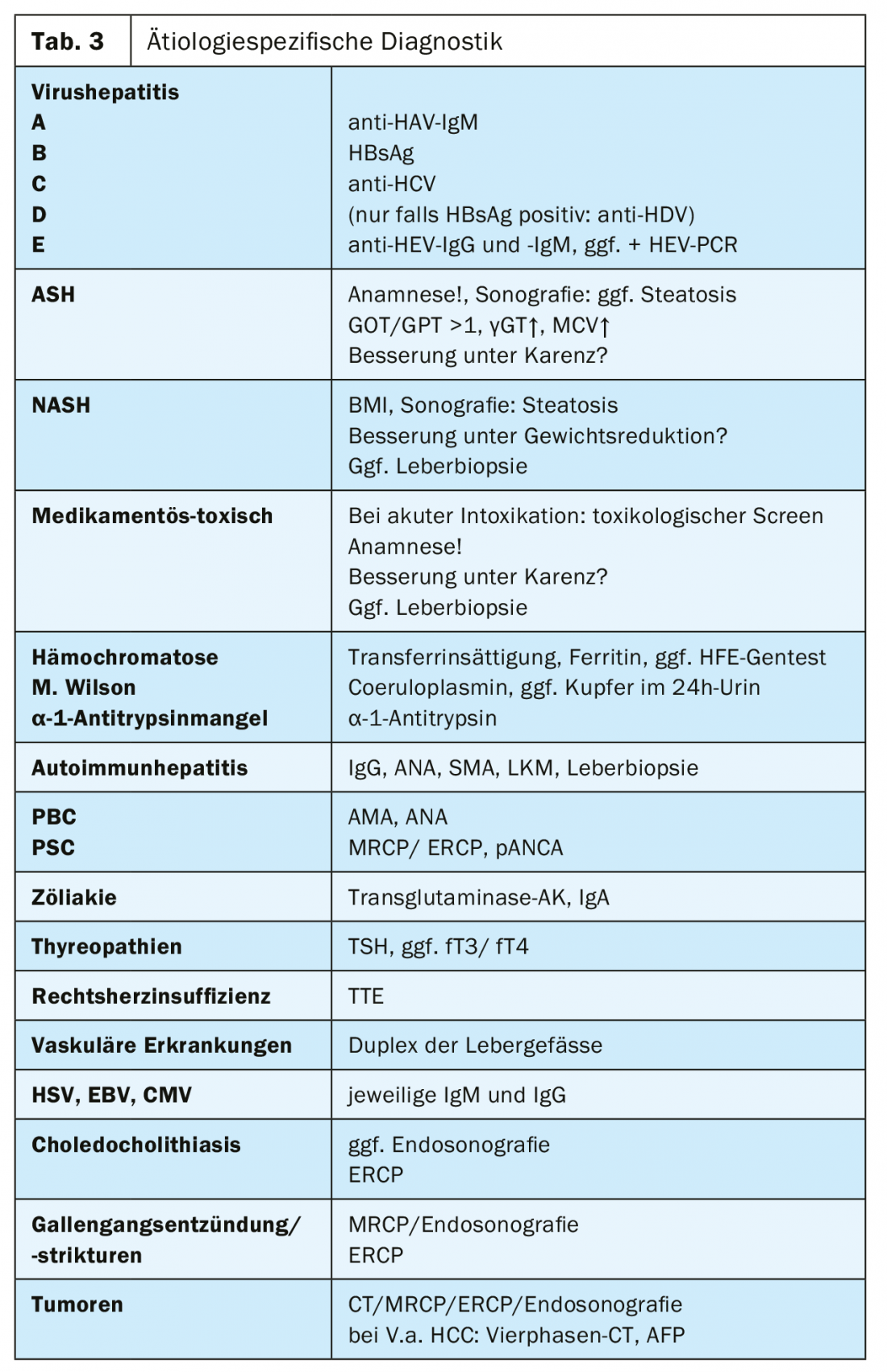

Etiologically, the entire spectrum of differential diagnoses must be considered in acute hepatitis, because almost all liver diseases can also manifest acutely. For many etiologies, the primary diagnosis can be reduced to one or two serological markers (Table 3). If the diagnosis cannot be established with these markers, further investigations such as liver puncture or cross-sectional imaging may be required. Because many diseases leave typical histologic patterns of damage, liver puncture should be used generously as an additional diagnostic tool in cases of diagnostic uncertainty in acute hepatitis.

In the present case, basic diagnostics revealed no evidence of alcoholic hepatitis, drug toxicity, sepsis, or heart failure; vascular causes were not found sonographically. The following diagnostics were added to clarify viral hepatitides, autoimmune and hereditary liver diseases:

|

Based on the results, a diagnosis of acute hepatitis E virus infection can be made. It is typically caused by consumption of inadequately cooked pork and game meat, heals in immunocompetent patients, and therefore requires only symptomatic therapy in the present case. The number of hepatitis E cases has increased significantly in recent years, mostly due to increased diagnostic attention, and is higher than the hepatitis A case rate [3]. Therefore, hepatitis E should already be clarified in the primary diagnosis of acute hepatitis.

In general, viral hepatitis is the most important differential diagnosis of acute hepatitis besides toxic damage. Triggers can be all hepatitis viruses, which must be tested accordingly. Only hepatitis D, which can only occur as a co-infection or superinfection with existing hepatitis B virus infection, requires testing only when a positive HBsAg is detected. While travel and food history provide clues for fecal-orally transmitted hepatitis A and E, hepatitis B and C may be considered in patients with iv drug use, sexual risk behaviors, or occupational contact with blood.

In the present case, EBV and CMV infection were excluded as also common causes of acute hepatitis. With normal serum markers of iron and copper metabolism, hemochromatosis and Wilson’s disease can be considered sufficiently unlikely. Detection of autoantibodies or elevated IgG in the immunology laboratory would indicate autoimmune hepatitis (AIH); a condition typically found in midlife patients with possible other autoimmune diseases. A liver biopsy is formally required to confirm the diagnosis; the histological results, such as IgG, autoantibodies, and the exclusion of viral hepatitis, are incorporated into a score for diagnosis [4]. Therapy of AIH is based on immunosuppression with corticosteroids and azathioprine.

Case 2: Cholestatic laboratory patternIn a 56-year-old female patient, the following elevated liver values are detected during a laboratory check-up with normal Quick and albumin: GPT 67 U/l, GOT 61 U/l, γGT 212U/l, AP 431 U/l, total bilirubin 2.0 mg/dl. Anamnestically, the patient is asymptomatic except for mild fatigue. The clinical examination is unremarkable. Sonographically, there is no intra- or extrahepatic cholestasis, the gallbladder is unremarkable, chronic liver parenchymal damage is not evident, and liver perfusion is regular. |

In this case, cholestasis parameters are predominantly elevated. In this constellation, sonography is the key diagnostic tool to differentiate between diseases with mechanical cholestasis and cholestatic hepatopathies without visible cholestasis. This determines the further procedure: mechanical cholestasis suggests differential diagnoses such as tumors, stones or strictures and almost always requires diagnostic-therapeutic ERCP with bile drainage. If necessary, endosonography or cross-sectional imaging (MCRP or CT) is added for more detailed assessment. Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), which affects all bile ducts and can occur both with and without dominant stenosis and consecutive cholestasis, has a special role.

A cholestatic pattern without sonographic cholestasis may also occur in drug-toxic damage and in the second so-called cholestatic hepatopathy besides PSC, primary biliary cholangitis (PBC). Like AIH, both diseases belong to the group of autoimmune hepatobiliary diseases. Clinically, PBC, like AIH, tends to affect women; in contrast, PSC, which mostly affects men, is often associated with inflammatory bowel disease. There are overlap syndromes between all three, which is why all corresponding immunological markers should be tested. In the present case, the following diagnostics were added:

|

PBC-specific antimitochondrial antibodies (AMA) were detected. In the case of a chronically existing cholestatic laboratory pattern, this can already establish the diagnosis of PBC [5]. Therapy consists of the administration of ursodeoxycholic acid. Under this, disease progression can be completely prevented in up to two-thirds of patients.

Because of their general frequency and described cholestatic courses, chronic viral hepatitides B and C were included in this patient based on their respective serologic screening markers. All other causes of cholestatic hepatopathy are very rare and do not require primary testing. However, if the values are clearly elevated and the diagnosis is unclear, an MRCP or liver biopsy should be performed for further clarification, even in the case of a cholestatic laboratory pattern.

Case 3: Liver cirrhosisElevated liver values are to be clarified in a 36-year-old patient. The laboratory shows the following changes: GOT 76 U/l, GPT 64 U/l, γGT 101 U/l, AP 40 U/l, total bilirubin 3.7 mg/dl, Quick 48%, albumin 3.4 g/dl. Blood count: leukocytes 2.4 thousand/µl, platelets 45 thousand/µl, hemoglobin 14.2 g/dL. The patient had a history of thicker legs and mild itching. No concentration problems. No known pre-existing conditions except for obesity; no medication use, no drugs, no sexual risk behaviors. Alcohol: 2-3 beers on the weekend. Blank family history. Examination reveals a markedly obese patient (BMI 45 kg/m2) with gynecomastia, mild sclerenic terus, and ankle edema. Sonographically, the liver parenchyma is hyperechogenic with attenuation of sound (steatosis hepatis grade III), rounded marginal angle and barely visible hepatic veins. At 11 cm/s, portal vein flow is decreased. There is splenomegaly (22×7 cm) without ascites. Complemented elastography is suggestive of cirrhosis with a markedly increased liver stiffness of 38kPa. |

Compared to the previous cases, the diagnosis of liver cirrhosis must be made here at a young age on the basis of liver function parameters and sonography with elastography. At initial diagnosis, screening for preexisting complications should be performed. This includes sonography for the presence of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) or ascites, as well as gastroscopy to determine variceal status.

Finding and treating the etiology in cirrhosis is paramount as this helps to improve liver function and even fibrosis in some cases. In addition, the correct diagnosis is a prerequisite for evaluating the option of liver transplantation.

In the patient, body mass index and laboratory evidence of steatosis suggest nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) – one of today’s leading causes of transaminase elevations and liver cirrhosis. Their frequency as a reason for liver transplant listing has increased dramatically over the past 15 years [7]. The diagnosis can be confirmed by liver biopsy, which may show ballooning, fatty degeneration, and partial necrosis of hepatocytes, as well as inflammatory cell infiltrates.

|

Standard values |

Ultimately, however, it is also a diagnosis of exclusion, so that the clarification must again proceed in a structured manner. Laboratory chemistry revealed a hepatocellular inflammatory pattern in the patient with, however, only mild transaminase elevation in the sense of chronic asymptomatic hepatitis. Normally, when values are elevated up to twice the upper norm, it would first be possible to wait for a follow-up in 1-3 months [1] to be able to distinguish a nonspecific passive from a true chronic liver elevation. However, chronicity has been proven in the present case with pre-existing cirrhosis. In addition, normal transaminases may also be present transiently in cirrhosis; an underlying cause should nevertheless be clarified immediately because of the therapeutic urgency. In the spectrum of differential diagnoses, those diseases may now be omitted which alone cause acute, healing hepatitis. These include hepatitis A and systemic herpes virus infections. Hepatitis E would have to be tested in the case of immunosuppression, as chronic courses can occur here.

In the present case, the relevant differential diagnoses of chronic hepatitis could be excluded:

|

Moreover, two of the most common causes, alcoholic steatohepatitis (ASH) and chronic drug-toxic damage, could be excluded on the basis of the medical history. The credibility of the alcohol history must be questioned individually in each case. If necessary, forensic determination of the CDT level can be performed, also with regard to liver transplantation.

The testing of hepatitis B and C is essential in the clarification of chronic hepatitis, as very good therapeutic options are available here: With the introduction of direct antiviral substances for the therapy of chronic hepatitis C, a cure of the infection has become possible in almost all patients in the last ten years. Antiviral agents are also available for chronic hepatitis B infection, and although they only provide cure in <10%, they provide reliable viral suppression on a sustained basis [6].

The most common of the hereditary hepatopathies is hemochromatosis, so in this case an HFE gene test was added in the presence of elevated ferritin and markedly elevated transferrin saturation, but this excluded it in wild type. An increase in ferritin is often found in liver cirrhosis as a manifestation of chronic liver inflammation. Similarly, hypergammaglobulinemia and cytopenia are common, as in the present case. The latter can be adequately explained in the context of the marked splenomegaly present here, which is due to portal hypertension, and does not require further specific workup.

In synopsis of the findings, this patient can indeed be diagnosed with cirrhosis on the floor of NASH. Therapeutically, various drugs are currently being tested in trials for NASH; however, a relevant response has not yet been demonstrated. Nevertheless, there is a very reliable and highly effective therapy: weight loss. A reduction in body weight of >10% leads to a response in terms of a decrease in transaminases and fatty liver in >80% of cases [8].

Take-Home Messages

- Elevated liver values should always be taken seriously and clarified, as only then can the cause be treated and the gradual progression of liver disease prevented.

- For the initial classification in the sense of rational efficient stepwise diagnostics, the combination of anamnesis, examination, liver sonography and basic hepatological laboratory (transaminases, cholestasis parameters, liver function parameters) is already sufficient.

- Laboratory classification into “hepatocellular inflammatory pattern” versus “cholestastic pattern” provides a good categorization for further diagnosis; in the latter, sonographic evaluation of mechanical cholestasis allows further subdivision.

- Many diseases can already be clarified by simple laboratory diagnostics. If necessary, a liver biopsy or cross-sectional imaging is complementary.

- The higher the liver values, the more rapid and broad the differential diagnosis must be chosen.

- The presence of chronic hepatic parenchymal damage should always be evaluated in the evaluation of elevated liver enzymes. Even in cirrhosis, the treatment of etiologic factors and complications allows a positive influence on the course of the disease.

Literature:

- Kwo PY, Cohen SM, Lim JK: ACG Clinical Guideline: Evaluation of abnormal liver chemistries. Am J Gastroenterol 2017; 112(1): 18-35.

- Zimmermann H, et al: Elevated liver values – what now? Dtsch Arztebl 2016; 113(22-23): A-1104 / B-924 / C-910.

- Robert Koch Institute: Infection Epidemiology Yearbook of Notifiable Diseases for 2016. Berlin, 2017.

- Hennes EM, et al: Simplified criteria for the diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology 2008; 48(1): 169-176.

- Hirschfield GM, et al: EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: The diagnosis and management of patients with primary biliary cholangitis. J Hepatol 2017; 67(1): 145-172.

- Luxenburger H, Thimme R, Neumann-Haefelin C: Viral hepatitis – when to think about it? Dtsch med Wochenschr 2019; 144(8): 520-527.

- Wong RJ, et al: Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis is the second leading etiology of liver disease among adults awaiting liver transplantation in the United States. Gastroenterology 2015; 148(3): 547-555.

- Vilar-Gomez E, et al: Weight loss through lifestyle modification significantly reduces features of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology 2015; 149(2): 367-378.

FAMILY PRACTICE 2019; 14(6): 9-14