Bronchial asthma is a common disease. The initial diagnosis is made by the family physician. For stable, controlled asthma, monitor lung function every one to two years.

Bronchial asthma is a pervasive problem in family practice and, as such, is not always easy to manage. It needs frequent follow-up and also teaching of the patients. The practice-oriented guidelines, known as GINA guidelines [1], provide an annual update on:

- Diagnosis

- Management in the stable phase (step scheme) and exacerbation

- Importance of comorbidities/precipitating factors.

- Overlap of asthma and COPD

- Non-controlled (“severe, persistent”) vs. “difficult to treat” asthma, risk factors, referral.

The following is a simplified presentation focused on practical aspects; detailed information is provided in the references.

Epidemiology, definition, forms

The incidence is about 5-7% of adults and up to 10% of children in the European population. A total of approximately 300 million people worldwide are affected, incidence increasing (especially in children). The disease has a high cost – about 1-2% of the health budget in developed countries.

Asthma is a heterogeneous disease characterized by recurrent airway obstruction that is reversible spontaneously or with therapy. Underlying is a chronic inflammatory response of the airways (with cough and mucus production) leading to hyperreactivity to various stimuli and obstruction.

There are the following forms/phenotypes:

- Extrinsic (atopic/allergic): More like eosinophilic inflammation. Subtypes: Onset in childhood (better prognosis) or late (after puberty).

- Intrinsic (recurrent infections/rhinosinusitis): More neutrophilic inflammation.

- Exercise-induced [2] (6-8 min after exercise): Treated as a separate entity

- Samter-Widal disease (new term: “aspirin exacerbated respiratory disease”): Characterized by the triad of asthma, nasal polyposis, and aspirin intolerance.

- Overlap of bronchial asthma and COPD (asthma-COPD overlap, ACO): Parallel treatment of both diseases

- Postmenopausal asthma: neutrophilic, associated with GERD and obesity.

Clinic

The clinic consists of whistling breathing (“wheezing”) and prolonged expiration, whether spontaneous or only with forced expiration. In addition, there is a history of cough (especially at night), recurrent episodes of whistling breathing, dyspnea, and thoracic oppression (equivalent of dynamic pulmonary hyperinflation, volume pulmonum auctum in extreme cases). Symptoms occur at night or worsen (patient wakes up). Seasonal deterioration is also taking place. Moreover, protracted airway infections (more than ten days) are characteristic of the clinic.

Atopy may present via eczema, atopic dermatitis, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, or positive family history.

Triggering factors/stimuli of bronchial hyperresponsiveness include:

- Animal hair

- Aerosols (chemical substances)

- Temperature changes, especially cold and dry air

- House dust

- Medications (aspirin®, NSAIDs, beta-blockers, Mestinon®, adenosine)

- Physical exertion/stress

- Pollen

- Respiratory infections (especially viral)

- Smoke (cigarette smoke, smoking pot)

- Strong emotions (Circulus vitiosus: asthma hyperventilation)

- Menstruation

- Mouth breathing with obstructed nasal breathing (drying of the airways).

Diagnosis ex juvantibus in terms of symptom response to antiasthmatic therapy is potentially possible, but the principle of “diagnosis before therapy” should be adhered to.

Diagnosis (evidence of obstruction/reversibility).

Spirometry:

- Obstruction: FEV1/FVC <70% (75% in young patients).

- (Partial) reversibility: increase in FEV1 ≥12% and ≥200 ml 15 minutes after two strokes of Ventolin®, but FEV1/FVC remains <70%.

- Complete reversibility: increase in FEV1 ≥12% and ≥200 ml after two strokes of Ventolin® and FEV1/FVC >70% means normalization of spirometry.

Peak Expiratory Flow (PEF) is a cooperative parameter and needs training:

- % from the best value of the patient

- Increase in PEF ≥20% and 60 l/min. after two strokes Ventolin®

- Daily variation PEF ≥20% (or ≥10% if measured twice).

- Method useful in reliable patients with severe asthma and little perception for obstruction.

A methacholine/mannitol bronchoprovocation test is indicated only if no obstruction has been demonstrated by that time (normal lung function):

- Graded by cumulative methacholine concentration resulting in 20% decrease in FEV1 (bronchoconstriction).

- Pay attention to symptoms typical for the patient (can they be reproduced?)

- Auscultation, checking nasal breathing, facial flush (histamine effect), stridor (DD: “vocal cord dysfunction”).

- Recovery of FEV1 drop (and discomfort) after broncholysis (15 minutes after two breaths of Ventolin®).

Additionally useful are a chest X-ray in two planes (“not everything that whistles is asthma”), IgE total and sx1 (RAST for common inhalant allergens), optional FeNO (“fractional exhaled nitric oxide”, marker of eosinophilic airway inflammation at diagnosis and as a follow-up parameter) and blood sampling (eosinophilia? If no p.o. cortisone therapy).

Helpful diagnostic clues more suggestive of asthma include the presence of more than one symptom (whistling, dyspnea, cough, thoracic tightness), worsening of symptoms at night/near morning, variability of symptoms in time and intensity, and triggering of symptoms by named precipitating factors.

Cough alone (caveat: asthmatic cough variant), chronic sputum production, dyspnea associated with dizziness, “empty head” and tingling (Nijmegen questionnaire for diagnosis of hyperventilation), and chest pain and exertional dyspnea with inspiratory stridor tend to argue against asthma.

The differential diagnosis includes:

- COPD (cortisone shot over ten days with massive lung function improvement means chronic asthma).

- Cardiopathy/heart failure: asthma cardiale vs. asthma bronchiale

- Obstruction of other genesis (e.g., sarcoidosis, cystic fibrosis).

- “Vocal cord dysfunction” (asthma and a psychogenic overlay often go hand in hand).

- Churg-Strauss vasculitis: difficult-to-control asthma with eosinophilia

- Allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA)

- Foreign body aspiration

- Non-obstructive pulmonary disease

- Polymorbid, especially elderly patients with overlapping diagnoses as the cause of dyspnea/respiratory symptoms.

Asthma control concept

The basic principle is that asthma can be controlled but not cured. If it is not well controlled, it becomes potentially dangerous. Asthma management, in practical terms, consists of three pillars that are reviewed recurrently: Assessing diagnosis, symptom control and risk factors (lung function!), inhaler technique and adherence and patient preference, adjusting asthma medications (“controller” medications), non-pharmacological strategies and modifiable risk factors, reviewing response regarding symptoms, exacerbations, side effects, patient satisfaction and lung function.

With the goal of asthma control in mind, symptoms should be revised every four weeks (Asthma Control Test, ACT, www.asthmacontroltest.com). Risk factors for a complicated course that are independent of symptom control include intubation due to asthma, occurrence of more than one exacerbation in the past year, low FEV1 (at diagnosis, during the course, individual best value, periodically later, at least once a year), incorrect inhalation technique and/or poor adherence, smoking (smoking pot), increased FeNO in adults with allergic asthma, obesity, pregnancy and blood eosinophilia.

Risk factors for fixed obstruction include lack of ICS therapy, smoking, occupational exposure, mucus hypersecretion, and blood eosinophilia.

In turn, risk factors for drug side effects include frequent steroids p.o., high doses of potent ICS, and P450 inhibitors as comedication.

Treatment plan

The goal is a good quality of life for the patient. This is initially achieved by freedom from symptoms (good control), even during physical exertion (ACT). In addition, the patient should be able to maintain normal daily activity. Exacerbations and medication side effects should be avoided if possible, and normal, or near-normal, lung function should be maintained. The patient must be protected from asthma mortality.

An important component of therapy is therefore the establishment of a good patient-doctor relationship. One should identify risk factors early and try to reduce them. Patient education on self-monitoring is provided as part of the evaluation, therapy and monitoring of asthma. A management plan (including exacerbations) is jointly implemented.

Treatment stages

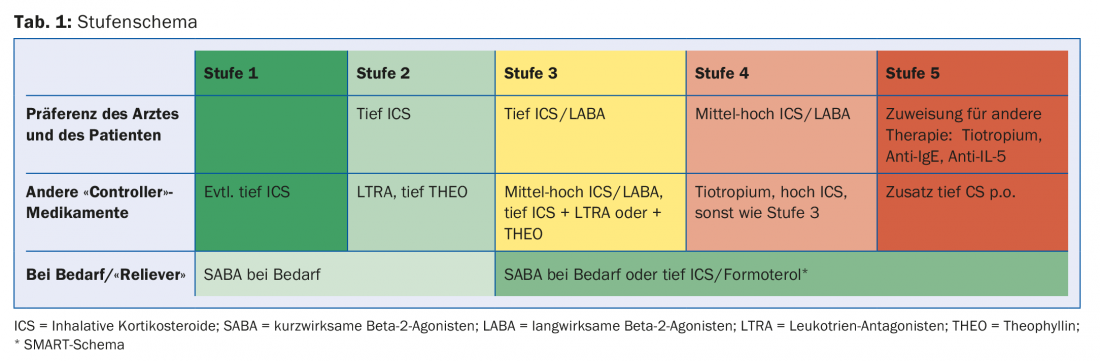

Table 1 shows the treatment stages schematically. When is a step change indicated? Long-term upstaging occurs for three months (until control is obtained) because bronchial hyperresponsiveness takes time to recover under controller medications. A mid-term step-up is in terms of doubling the current dose of ICS/LABA for two weeks for respiratory infections.

Upgrading requires day-to-day flexibility depending on complaints. The SMART concept (Symbicort® Maintenance and Reliever Therapy) comprises the basic therapy 2×/d and, if required, e.g. up to four more strokes spread over 24 hours. If the reserve is used up frequently (on several days in a week), it does not indicate good control.

Another approach is “start high, then step down.” Patients tend to wait too long to present to the doctor with complaints. Psychologically, they benefit from rapid control of symptoms and gain confidence in the therapeutic approach. After three months, when there is good control, gradation is often possible.

Medication

Short-acting betamimetics (SABA): Best given only in reserve. If the reserve is used up for two to three days, there is no good control. SABA operate a pure cosmetics, have no controller properties. Because of the noticeable bronchodilator effect, there is a risk of abuse and side effects. Therefore, clearly communicate the upper limit of the daily reserve (maximum 4× 2 strokes from DA, 100 mcg each, or 4× 1 stroke from Diskus, 200 mcg each).

Long-acting betamimetics (LABA): are prohibited as monotherapy (mortality increase because no controller properties), but potent in combination with ICS. That is why nowadays mainly combination preparations are used.

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS): are the cornerstone of controller medications. There are many, especially combination preparations with LABA (compare dose lists in GINA).

Leukotriene antagonists: are particularly useful in allergic asthma, have few side effects and are also approved as long-term therapy in children.

Theophylline: The daily dose is variable because there is very wide interindividual variation in pharmacokinetics (target level 8-20 mcg/ml). Give retard preparations and creep in. As a rule of thumb, smokers need more, and in severe exacerbations with hypoxemia, give less (more side effects). Many drug-drug interactions occur.

Tiotropium: Because of the overlapping indication in COPD and currently still in asthma, differential diagnostic thinking is not encouraged. It acts more in the larger bronchi. Is a good new addition to controller medications.

New potent controllers: In the eosinophilic phenotype (stage 5), there is the anti-IgE antibody omalizumab (Xolair®) with already eleven years of experience. The anti-IL-5 antibody mepolizumab (Nucala®) has been approved in Switzerland since 2015. The agents need appropriately elevated IgE and blood eosinophilia for the indication. They must be used s.c. monthly on a trial basis for at least four months; if effective, therapy is continued.

Caution: At low peak flow <60% (from the best individual value), inhalations with any substance (in DA, discus or TH) are not sufficiently efficient, because there is not enough bronchial deposition (for the most part anyway deposition in the pharyngeal area). With a prechamber (Vortex®, AeroChamber®), the speed of the spray jet is slowed down, resulting in better bronchial deposition. Coordination between triggering the stroke and inspiration is not critical. However, only the DA is compatible with the ballast chamber.

With all inhalatives, systemic absorption (and theoretically thereby side effects), and with ICS also candidiasis of the oral mucosa, can be minimized by rinsing the throat and oral cavity.

Management of exacerbations

The following “red flags” must be observed:

- Common in asthma attack: tachypnea 25-28/min, pulse about 100/min.

- FEV1 at approx. 30-35% target (absolute around 1 l)

- Peak flow approx. 150 l/min.

- Auscultatory wheezing only at peak flow >25% reduction (from individual best value)

- At FEV1 15-20% Target: pCO2 normalizes, impending respiratory decompensation.

- FEV1 <15% target (absolute 500 ml): “silent chest” with acute respiratory acidosis.

- Alert for bradycardia, pulsus paradoxus, dyspnea of speech, somnolence, cyanosis.

Difficult to control asthma

DTA (“difficult to treat” asthma) [3] can only be considered after six months of treatment by a pulmonologist if there is no sufficient control despite two controller medications (including steroids per os).

In any case, compliance should be evaluated for DTA. Is there possibly still a complicated scheme/management plan in place? Are there any medication issues e.g. regarding inhalation technique or side effects? Does the patient smoke (active, passive, smoking pot)? Exposure to allergens/trigger factors – mentioned above – should also be assessed (including commercial allergens/irritants, “occupational asthma”), as well as gastroesophageal reflux, “post nasal drip” (“upper airway cough syndrome”) in chronic rhinosinusitis/other ENT problem and OSAS. Is there a psychic overlay (“vocal cord dysfunction”) or other diagnoses such as ABPA, Churg-Strauss syndrome, foreign body, tumor, heart failure, bronchiectasis, recurrent aspiration?

Many of the above factors and diagnoses occur together. In studies, >50% of patients with DTA and frequent exacerbations have three or more comorbidities [4].

When to refer to pulmonologist?

The initial diagnosis is made by the general practitioner, and confirmation is made by the pulmonologist, also because of the possible methacholine test and differential diagnoses. Suspicion of ACO or occupational asthma can be verified pneumologically.

Persistent, uncontrolled asthma with frequent exacerbations, low FEV1 despite good adherence and inhalation technique at level 4 (or even level 3, as there is suffering) should also be clarified with a pulmonologist. He is a target site for significant medication side effects (especially if steroids per os are necessary) or for suspected comorbidities such as rhinosinusitis (triadic asthma) or sputum production and radiographic changes (ABPA). Patients with risk factors for asthma-associated death, i.e., history of near-fatal exacerbation/intubation or anaphylaxis in food allergy with asthma, also belong in pneumologic hands.

Take-Home Messages

- Bronchial asthma is a common disease with a potentially dangerous course.

- The initial diagnosis is made by the general practitioner, and confirmation is made by the pulmonologist (also because of differential diagnoses).

- “Difficult asthma” should always be co-managed by the pulmonologist.

- For stable, controlled asthma, monitor lung function every one to two years.

Literature:

- Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA): Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention. Update 2017. www.ginasthma.com

- Maurer M: Bronchial asthma – exertional asthma and sports. Family Practice 2016; 11(11): 32-36.

- Chung KF: Clinical management of severe therapy-resistant asthma. Expert Review of Respiratory Medicine 2017; 11(5): 395-402.

- Ten Brinke A, et al: Risk factors of frequent exacerbations in difficult-to-treat asthma. Eur Respir J 2005; 26: 812-818.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2017; 12(12): 9-12