On January 11, 2018, the 21st Annual Meeting of the Swiss Brain Stroke Society was held in Lausanne. An important topic was vasculitides, which, if they affect the CNS, can trigger a stroke. There are no evidence-based guidelines for the therapy of primary CNS vasculitis – all the more important are cohort studies and recommendations from experts.

Dr. Grégoire Boulouis, Neuroradiology at Saint-Joseph Hospital, Paris, and University Paris-Descartes, Paris (F), provided information on the causes and differential diagnoses of the various vasculitides and how they present on imaging when they lead to neurologic complications.

Vasculitides and Stroke

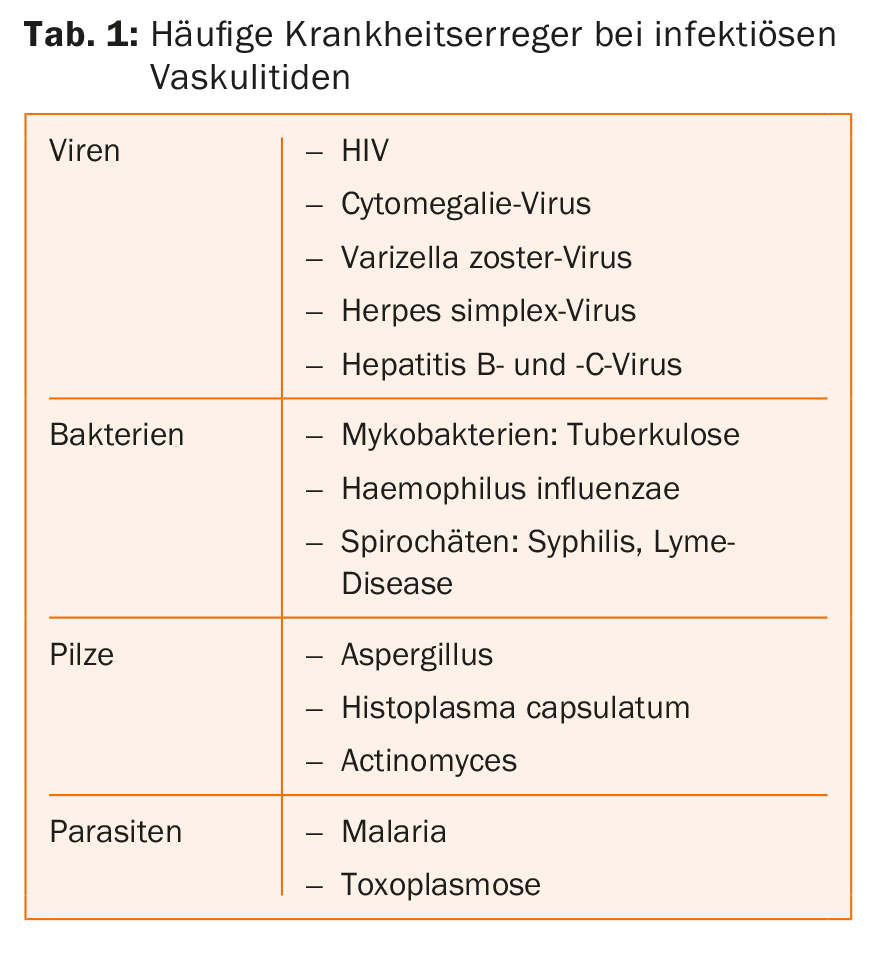

Basically, a distinction is made between infectious (Tab. 1) and non-infectious vasculitides. Most commonly, these occur as secondary symptoms in systemic diseases such as lupus erythematosus, sarcoidosis, or tumors-often the prognosis is poor in these diseases when the CNS is involved. Temporal giant cell arteritis (Horton’s disease) is at particularly high risk for stroke, occurring primarily in individuals over the age of 50 and can rapidly lead to blindness if left untreated. Takayasu vasculitis, which affects the aorta and the large arteries branching off from it, is less common in Europe than in Asia. Patients are usually under 40 years of age, and 10-20% experience a stroke. Other causes of vasculitides include radiotherapy (radiation-induced angiitis) or toxic angiitis secondary to chemotherapy or heroin or cocaine abuse. A rare form is adult primary vasculitis of the CNS (aPACNS), which results in ischemic lesions in 75% of patients. These are multiple or disseminated in about half of patients. The diagnosis can only be made after exclusion of differential diagnoses and at the earliest after a follow-up of six months.

As a general rule, it should always be remembered that a stroke could be caused by vasculitis, especially if the presentation of symptoms is unusual or even bizarre. Diagnosis requires MRI imaging with various imaging protocols, such as those depicting intramural inflammatory signs. “Angiography can also provide clues to the diagnosis, especially if imaging is negative but vasculitis is highly suspected,” Dr. Boulouis said. Angiography can also be used to visualize the severity of vascular lesions.

Therapy of primary CNS vasculitis

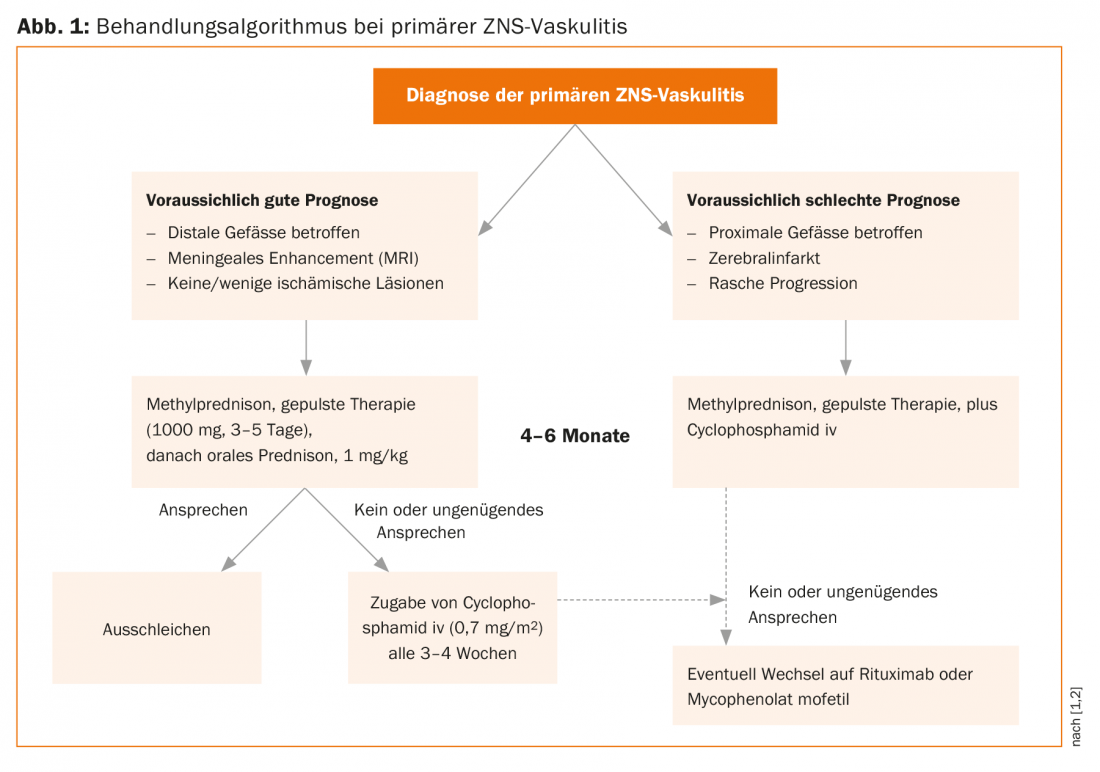

“Unfortunately, there is not much evidence on the treatment of patients with primary CNS vasculitis,” regretted Prof. Mathieu Zuber, Neurology, Saint-Joseph Hospital, Paris, and University of Paris-Descartes, Paris (F). For secondary CNS vasculitides, the best therapy is to treat the underlying disease. On the therapy of primary CNS vasculitides, only two cohort studies with larger patient numbers have appeared in the last decade (Mayo Clinic cohort: n=163, French cohort: n=97) [1,2]. The decision of whether, when, and what therapy to use must be made individually for each patient, based on the likelihood of vasculitis diagnosis and the results of diagnostic testing. Prof. Zuber mentioned that although brain biopsies are rarely performed nowadays, this option should not be completely forgotten, as weeks of wrong therapy can harm the patient more than a brain biopsy. “Vasculitis is a dynamic process, so it can be very useful to repeat diagnostic measures after four to six weeks,” he said. Risk factors for a worse course are an older age of the patient, the involvement of large vessels and the presence of a stroke – compared to patients who have not (yet) suffered a stroke. A good prognostic sign is gadolinium enhancement of leptomeninges on MRI. Enhancement indicates an infection that may be specifically treatable.

Corticosteroids, initially administered in pulses if necessary, are the therapy of choice. In patients not receiving steroids, the risk of death or severe sequelae is very high. Whether immunosuppressants should be administered in addition to steroids is controversial. In the Mayo Clinic cohort, 49% of patients received immunosuppressants; in the French cohort, 84% did. Although mortality and recurrence rates were lower in the French cohort, the speaker pointed out that the two studies cannot be directly compared.

In the past, immunosuppression was mainly administered with methotrexate, but today better tolerated drugs are available in the form of cyclophosphamide (Endoxan®) and rituximab (Mabthera®) (Fig. 1). Induction therapy with steroids and, if necessary, immunosuppressants lasts four to six months. It is not clear whether and for how long maintenance therapy must be given. In the French cohort, 49% of patients received maintenance therapy (mostly azathioprine), for an average of two years (range: 6-72 months). Among patients on maintenance therapy, 22% relapsed; among patients not on maintenance therapy, 45% relapsed. “Because there are so many unanswered questions in the treatment of this disease, randomized-controlled trials would be particularly important,” Prof. Zuber concluded.

Acute stroke therapy – prehospital management.

Prof. Urs Fischer, MD, Co-Head of the Stroke Center Inselspital Bern, explained the Stroke Therapy Directives 2018:

- Time is Brain” still applies: patients must be treated as quickly and effectively as possible.

- Patients with large vessel occlusion (LVO) must be transferred immediately to a stroke center where endovascular therapy (EVT) is possible.

- Patients without occlusion of a major vessel must be transferred immediately to a center where thrombolysis (IVT) can be performed.

There are several scores that can be used to determine the likelihood of LVO based on clinical criteria; however, when specificity is high, the sensitivity of these scores is low and vice versa. “Moreover, a stroke often progresses dynamically,” Prof. Fischer reminded the audience. “Clinical criteria can change in a matter of minutes.”

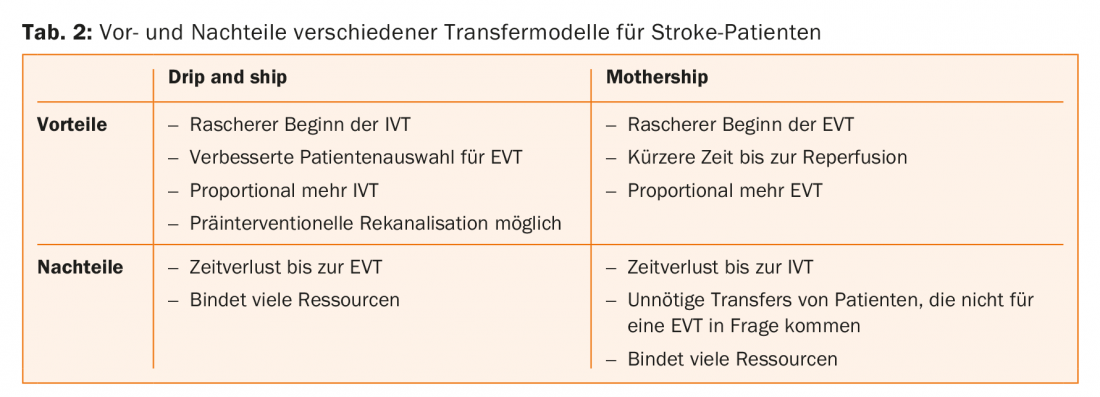

There are several strategies for getting the patient to specific therapy as quickly as possible. Mobile stroke units, while very effective, can only really be used effectively in large cities. In the “drip and drive” model, the interventiologist drives to the patient in the periphery – this model is practiced in Hamburg, for example. Two other models are realistic for Switzerland: “drip and ship”, in which the patient receives IVT in a peripheral hospital and is then transferred to the stroke center for EVT, and the “mothership” model, in which the patient is taken directly to the stroke center. Both models have important advantages and disadvantages, and currently there is no evidence on which option leads to better patient outcomes (Table 2).

Source: 21st Annual Meeting of the Swiss Brain Stroke Society, January 11, 2018, Lausanne.

- Vasculitis and stroke: Causes, imaging differential diagnosis (Dr. Grégoire Boulouis); Acute and chronic treatments (Prof. Mathieu Zuber)

- Hyperacute stroke management: New prehospital models for Switzerland (Prof. Dr. med. Urs Fischer)

Literature:

- Salvarani C, et al: Adult primary central nervous system vasculitis treatment and course: analysis of one hundred sixty-three patients. Arthritis Rheumatol 2015; 67(6): 1637-1645.

- de Boysson H, et al: Adult primary angiitis of the central nervous system: isolated small-vessel vasculitis represents distinct disease pattern. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2017 Mar 1; 56(3): 439-444.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2018; 16(1): 46-48.