Systems therapy for renal cell carcinoma is changing. Several tyrosine kinase inhibitors can significantly prolong survival in metastatic stages. Immunotherapies are also effective.

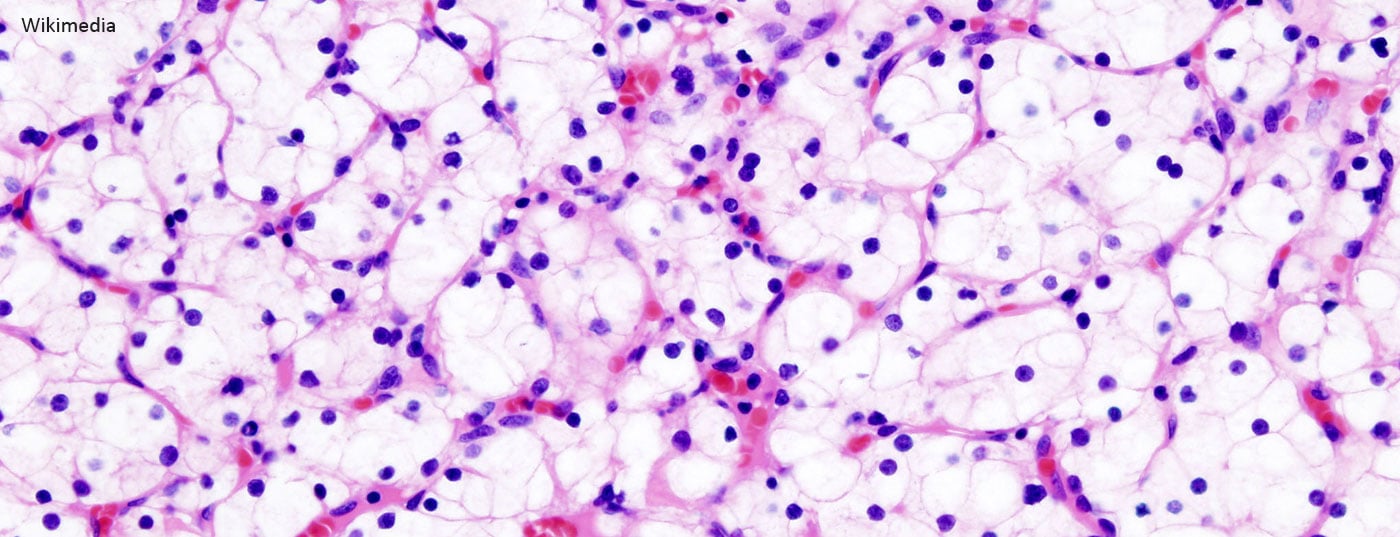

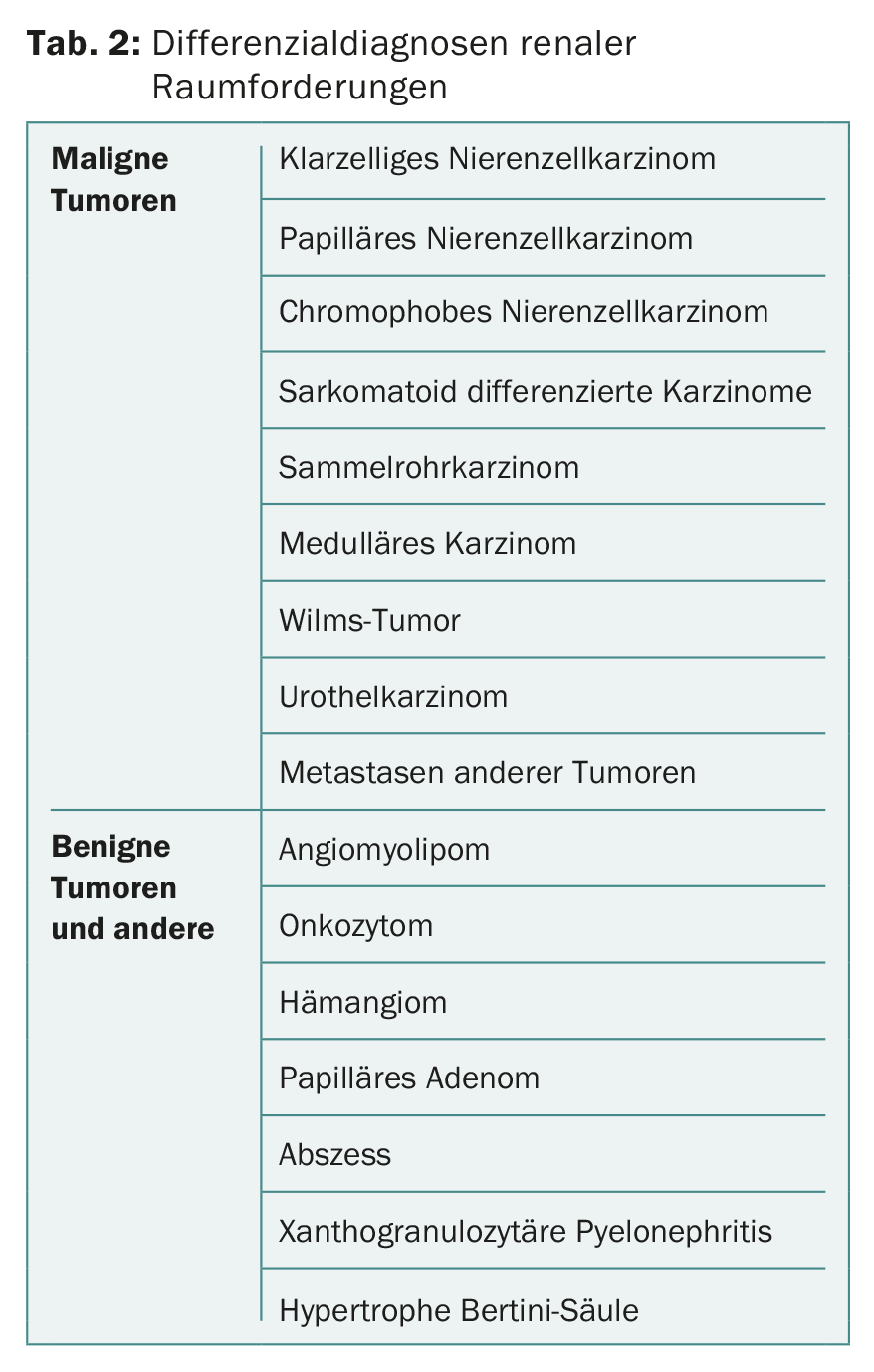

Renal cell carcinoma accounts for approximately 2-3% of all malignant tumors. The global incidence in 2012 is estimated at 338,000 cases with 144,000 tumor-associated deaths. Renal cell carcinoma is thus ranked 13th worldwide in terms of incidence [1–3] . After prostate carcinoma and urothelial carcinoma of the urinary bladder, it is the third most common urological tumor. The term “renal tumor” encompasses a broad spectrum of heterogeneous tumors as well as different histopathological entities. The three most common subtypes are clear cell, papillary, and chromophobe renal cell carcinoma, which together account for approximately 85-90% of all renal malignancies and of which the clear cell subtype has the worst prognosis [4]. In about 10-15% of cases, renal tumors are benign [5]. The most common benign renal tumors are oncocytoma and angiomyolipoma.

Epidemiology

The main age of onset of renal cell carcinoma is between the ages of 60 and 70 [5,6]. Men are affected more often than women, approximately in a 1.5:1 ratio. Risk factors include smoking, obesity, hypertension, and chronic renal failure [5,6]. A small proportion of renal cell carcinomas are hereditary, with Von Hippel-Lindau syndrome (VHL), tuberous sclerosis, and Birt-Hogg-Dubé syndrome being worthy of mention in this context.

Diagnostics

Most renal cell carcinomas today are diagnosed incidentally, i.e., as an incidental finding in an imaging study with a different medical question, and are asymptomatic at the time of initial diagnosis. Since kidney tumors are thus more often diagnosed at an early stage than in the past, a so-called “stage shift” has occurred in recent decades [5,6]. The classic symptom triad of flank pain, macrohematuria, and palpable abdominal tumor is now very rare. However, if these local symptoms are present, the tumor is usually already locally advanced and metastatic, with a consecutive poor prognosis. The general physical examination plays a rather minor role in the diagnosis of renal cell carcinoma. However, new-onset varicoceles or lower extremity edema may be indicative of retroperitoneal space-occupying lesions, which should consequently be excluded by imaging [6]. Renal tumors can cause various paraneoplastic symptoms [6].

Abnormal renal findings on ultrasonography should be further clarified with contrast-enhanced multiphase computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen or MRI. In special cases, contrast-enhanced sonography may be helpful [5]. Space-occupying lesions of the kidney are generally divided into solid and cystic lesions. Cystic lesions are divided into five categories (I, II, IIF, III, IV) for dignity assessment on CT using the BOSNIAK classification [7,8]. Category III and IV findings are considered malignant until proven otherwise, thus histologic clarification is indicated. In solid space lesions of the kidney, local uptake from the applied contrast medium (CM) is a particularly important malignancy criterion [5].

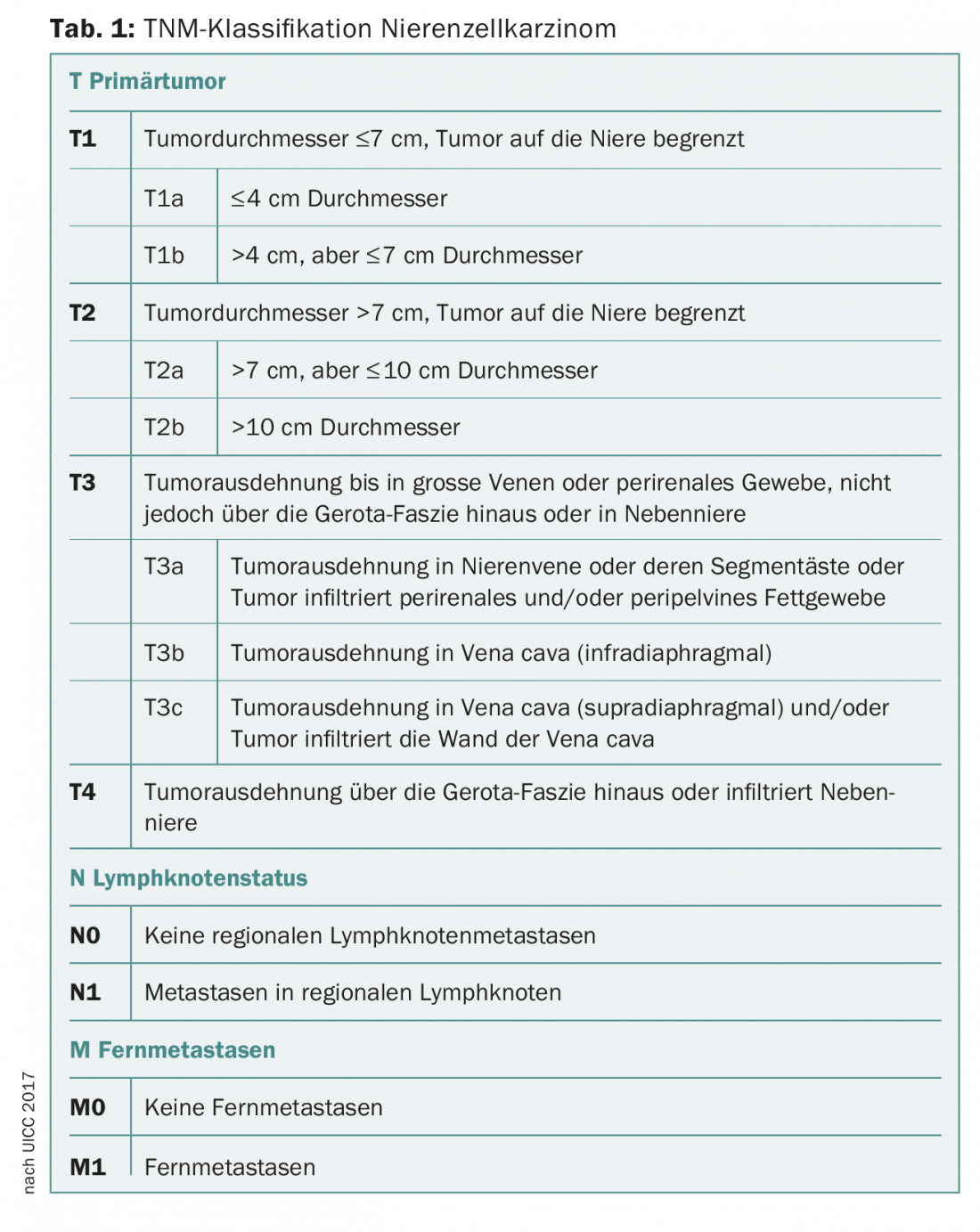

CT or MRI is used to assess the exact tumor location (central, peripheral, proximity to hilar or pyelon, etc.), local tumor extension, any vascular involvement (e.g., tumor thrombi in renal vein and vena cava), and suspicious lymph node enlargements, so that accurate staging can be performed according to the current TNM classification (Tab. 1) [5,6]. Difficulties in imaging diagnosis may be encountered in differentiating fat-free angiomyolipomas as well as oncocytomas from malignant processes [9]. If the presence of renal cell carcinoma is strongly suspected, supplementary CT of the thorax should be performed to exclude pulmonary metastases [5].

Whereas percutaneous renal tumor biopsy was once considered virtually contraindicated because of concerns about stent metastases, it is now being performed with increasing frequency. Biopsy has its place especially in radiologically unclear lesions, in small renal tumors before inclusion in an active surveillance strategy, before local ablative therapy or in metastatic tumor disease for histology acquisition [5,6,9]. In the case of metastatic renal tumors, this enables the choice of an appropriate system therapy. Also, renal tumor biopsy allows differentiation from metastases of other primary tumors. A biopsy can be performed either sonographically or CT guided. Possible differential diagnoses of renal space-occupying lesions are shown in Table 2.

Staging

Clinical staging of renal cell carcinoma is according to the current TNM classification (Table 1) [5,10]. The WHO/ISUP(World Health Organization/International Society or Urological Pathology) grading system replaces the histologic grading system developed in the 1980s and most widely used internationally, analogous to Fuhrmann [5,11,12].

Surgical therapy

Standard therapy for renal cell carcinoma is usually complete surgical removal of the tumor [9]. In localized renal cell carcinoma, this is done with curative intent. Historically, radical nephrectomy has long been the gold standard [6]. Today, depending on the location and size of the renal tumor, a nephron-sparing surgical technique in the sense of a partial kidney resection should be aimed for. Tumor-specific survival in localized renal cell carcinoma appears to be comparable after partial kidney resection and nephrectomy [5]. Retrospective data suggest that overall survival is better after partial renal resection for localized renal cell carcinoma than after nephrectomy [5, 13-15].

The current EAU guidelines recommend performing partial kidney resection for stage T1 renal cell carcinoma [5]. In principle, this can be performed openly, laparoscopically or robot-assisted. In stage T2, laparoscopic nephrectomy is recommended when performing partial kidney resection is not feasible [5].

Routine ipsilateral adrenalectomy does not appear to confer a survival benefit and is therefore performed only when tumor infiltration is suspected [5]. Lymph node metastases (pN+) are associated with a poor prognosis. However, the data regarding the significance of lymphadenectomy are controversial. Currently, according to current EAU guidelines, lymphadenectomy is recommended only in cases of clinical suspicion of lymph node metastases (cN+) [5]. In clinically unremarkable lymph nodes, it may be considered for large or sarcomatoid differentiated tumors. In already metastatic renal cell carcinoma, patients may be offered cytoreductive nephrectomy before initiation of systemic therapy, especially for large renal tumors [5].

Alternatives to surgery

In elderly patients with relevant comorbidities and/or limited life expectancy, alternatives to surgery may be discussed for localized renal cell carcinoma. In particular, small, incidentally diagnosed renal tumors can be monitored regularly with imaging in these patients (Active Surveillance) [5,9]. The growth rate of such space-occupying lesions and the risk of progression to the metastatic stage are low [5,6]. Initially, histologic confirmation of diagnosis by renal tumor biopsy may be helpful in this approach [6]. Clear triggers for switching to active treatment have not been defined. Minimally invasive treatment options such as cryoablation or radiofrequency ablation (RFA) can also be discussed in a selected patient population [5,6]. These procedures are performed either percutaneously or laparoscopically assisted. The current data do not yet allow a conclusive assessment of these therapies in terms of tumor control and morbidity. Selective arterial embolization may be considered for unresectable renal tumors symptomatic with, for example, flank pain or macrohematuria [5].

System therapy of renal cell carcinoma

Fortunately, the systemic treatment of advanced light cell renal cell carcinoma has improved greatly in recent years. It responds poorly to chemotherapy, but immunological responses have been known to play a role for some time. Thus, prolonged stabilizations and even regressions of lung or lymph node metastases can be observed after removal of the primary tumor. In 9% of patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma, treatment with interferon-alpha can produce remissions, although with considerable toxicity. The latter is still significantly higher with interleukin 2 treatments, but impressive remissions lasting for years can be observed in about 10% of patients.

In more than 80% of light cell renal cell carcinomas, a biallelic alteration of the VHL gene is present in the tumor with a resulting increased VEGF (“vascular endothelial growth factor”) formation, which is an important growth factor. Several tyrosine kinase inhibitors can inhibit VEGF receptors (as well as other receptors) and have been shown to be effective drugs in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. They have replaced the majority of the above drugs.

In the first-line therapy, the oral sunitinib and the not less effective but slightly less toxic pazopanib are currently the main options. In randomized trials, sunitinib demonstrated a response in 31% versus 6% with the then-standard interferon-alpha, and a prolongation to tumor progression from five to 11 months. Survival was also extended by 4.6 months – to 26.4 months. Side effects may include diarrhea, hypertension, fatigue, skin reactions, white hair, and thyroid dysfunction, as well as cardiac dysfunction. Cabozantinib may be more effective than sunitinib in first-line therapy, according to a new phase II study, but this needs to be confirmed in a phase III trial before it can become the new standard.

The above-mentioned mechanism of action also explains the efficacy of the monoclonal antibody bevacizumab, which binds VEGF. The combination with interferon-alpha is approved in first-line therapy.

According to study data, in renal cell carcinoma with poorer prognosis, the mTOR inhibitor everolimus is another option. Possible side effects include stomatitis and hematologic side effects. One indication for everolimus is failure of anti-VEGF-based therapy.

A tyrosine kinase inhibitor can also be used in second-line therapy (such as axitinib or sorafenib). The tyrosine kinase inhibitor cabozantinib significantly prolonged survival (21.4 vs. 16.5 months) in second-line therapy compared with everolimus [16]. The combination of lenvatinib with everolimus was even able to prolong survival by ten months in a phase II trial.

Recent interesting data show partly very good results with immunotherapy (checkpoint inhibitors). A phase III trial of nivolumab in the second-line setting showed a 5.4-month increase in median survival compared with everolimus to 25 months and a higher response rate of 25% vs. 5% [17]. Another advantage of this therapy is also the generally much lower toxicity, including various autoimmune diseases. However, we ourselves have also seen patients with severe side effects (e.g. an invalidating rheumatic disease lasting for months in the sense of polymyalgia rheumatica). Recently, it was shown (CHECKMATE-214 at ESMO 2017) that combined immunotherapy with nivolumab and ipilimumab is superior to sunitinib therapy in first-line therapy, especially when PD-L1 is expressed, with a higher response of 58% vs. 25% and a prolonged time to tumor progression of 22.8 vs. 5.9 months. Immunotherapies are thus advancing into first-line therapy as a result of these recent data. However, this superiority to sunitinib does not apply to patients in the good prognosis group.

The choice of third-line therapy is based on the previous treatments and their success.

Adjuvant treatment

Studies of adjuvant treatment after renal cell carcinoma surgery and at high risk of recurrence with different agents have been negative and controversial for years. Recent data [18] show that sunitinib over one year as adjuvant therapy in high-risk settings can increase the time to relapse from 5.6 to 6.8 years. However, this is currently still an off-label treatment.

Take-Home Messages

- The main age of onset of renal cell carcinoma is between the ages of 60 and 70.

- Depending on the location and size of the renal tumor, a nephron-sparing surgical technique should be pursued whenever possible.

- Percutaneous renal tumor biopsy is being performed with increasing frequency these days.

- System therapy for renal cell carcinoma is changing thanks to new drugs and combinations. Several tyrosine kinase inhibitors can significantly prolong survival in metastatic stages. Immunotherapies (checkpoint inhibitors) are also effective in metastatic stages.

- Adjuvant treatment is an option if the risk of recurrence is high.

Literature:

- Torre LA, et al: Global Cancer Statistics, 2012. CA: A Cancer J Clin 2015; 65(2): 87-108.

- Ferlay J, et al: Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer 2015; 136(5): 359-386.

- European Network of Cancer Registries: Kidney cancer (KC) Factsheet. February 2017. www.encr.eu

- Shuch B, et al.: Understanding pathologic variants of renal cell carcinoma: Distilling therapeutic opportunities from biologic complexity. Eur Urol 2015; 67(1): 85-97.

- Ljungberg B, et al: EAU guidelines on Renal Cell Carcinoma. European Association of Urology. Limited Update March 2017. www.uroweb.org

- Capitanio U, Montorsi F: Renal cancer. The Lancet 2016; 387: 894-906.

- Israel GM, Bosniak M: How I do it: evaluating renal masses. Radiology 2005; 236(2): 441-450.

- Warren KS, McFarlane J: The Bosniak classification of renal cystic masses. BJU Int 2005; 95(7): 939-942.

- Schmid HP: Trends in renal cell carcinoma – clarification course and localized therapy. info@oncology 2015; 5: 27-30.

- Edge S, et al: AJCC Cancer Staging Manual. 7th Edition. New York: Springer-Verlag 2010.

- Moch H: The WHO/ISUP grading system for renal carcinoma. Pathologist 2016; 37(4): 355-360.

- Dagher J, et al: Clear cell renal cell carcinoma: validation of World Health Organization/International Society of Urological Pathology grading. Histopathology 2017 Jul 18. DOI: 10.1111/his.13311 [Epub ahead of Print].

- Roos FC, et al: Survival advantage of partial over radical nephrectomy in patients presenting with localized renal cell carcinoma. BMC Cancer 2014; 14(1): 372.

- Zini L, et al: Radical versus partial nephrectomy: Effect on overall and noncancer mortality. Cancer 2009; 115(7): 1465-1471.

- Huang WC, et al: Partial Nephrectomy Versus Radical Nephrectomy in Patients With Small Renal Tumors-Is There a Difference in Mortality and Cardiovascular Outcomes? J Urol 2009; 181(1): 55-62.

- Choueiri TK, et al: Cabozantinib versus everolimus in advanced renal cell carcinoma (METEOR): final results from a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2016; 17: 917-927.

- Motzer RJ, et al: Nivolumab versus everolimus in advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 1803-1813.

- Ravaud A, et al: Adjuvant sunitinib in high-risk renal cell carcinoma after nephrectomy. N Engl J Med 2016; 375(23): 2246-2254.

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2017; 5(6): 23-26.