Systemic therapies for psoriasis have changed dramatically in recent years. In the past, light therapy or the conventional systemic therapies such as methotrexate, acitretin, ciclosporin A and the fumaric acid esters were mostly used. Today, these are increasingly replaced in the course of therapy by treatment with the newer biologics and the group of small molecules.

According to their importance in triggering disease flares, precipitating factors of psoriasis should be systematically eliminated: First and foremost, these include infections, stress, medications and inadequate skin care.

In addition to streptococcal infections, which are often blamed as causative factors, psychological stress is also considered to be an important provoking factor, especially in childhood and adolescence. Young people suffer more often from stigmatization, which can lead to major psychosocial conflict situations, especially during adolescence. Adolescents have an equal loss of quality of life from psoriasis as they do from acne.

Medications such as β2-blockers, ACE inhibitors, antimalarials, lithium, and NSAIDs can also provoke psoriasis, so a thorough medication history is important.

Last but not least, skin care is to be taken care of even when there is no appearance or minimal expression of disease. Regular use of skin care preparations not only helps to restore the disturbed barrier function of the skin, but also has the purpose of preventing the occurrence of new skin symptoms due to irritation such as dehydration (frequent bathing or showering, staying in heated rooms with low humidity). Therefore, the skin should be cared for daily with appropriate products.

Complete skin care series specially developed for psoriasis patients (e.g. Aqeo®), but also proven dermatological formulations or other skin care products are suitable for daily skin care, provided they are well tolerated by the patient.

Topical therapy

For infiltrated scaling plaques, descaling therapy with keratolytics is initially useful, not least to improve the penetration of active agents. Here it is recommended to use salicylic acid in concentrations between 5 and 10%, depending on the localization in a vaseline, carbowax or oil base. Other keratolytics include urea, lactic acid and colloidal sulfur.

While salicylic acid is essentially used to remove dandruff, urea (in concentrations between 8 and 12%), lactic acid (2.5-10%) and sulfur are suitable for care and treatment in the form of additives in creams, lotions or sulfur oil baths.

In children under 12 years of age, large-area topical application of salicylic acid-containing topical preparations may result in resorptive toxicity (salicylism) with damage to the central nervous system and kidneys. Therefore, the use of emulsifying creams such as Unguentum emulsificans aquosum, possibly with the addition of urea (5%), is more recommended for desquamation in children.

Once the plaques are desquamated, topical corticosteroids are used. These are among the most widely used topical therapeutics for psoriasis. They are characterized by very good efficacy and tolerability as well as – when used properly – low undesirable effects with a comparatively favorable price-performance ratio.

The negative evaluation of cortisone in the population lacks any medical-dermatological basis. Only if the duration of therapy is too long (uninterrupted therapy for more than six weeks) does cutaneous atrophy occur, although in many cases this can be irreversible. Typically, class III-IV steroids that are both anti-inflammatory and antiproliferative, such as clobetasol dipropionate (Dermovate®), betamethasone (Betnovate®), or, especially in children, mometasone furoate (Elocom®), are well effective, preferably in combination with topical vitamin D analogues such as calcipotriol (Daivobet®), tacalcitol (Curatoderm®), and calcitriol (Silkis®). These also occur in fixed combinations of betamethasone and calcipotriol for both skin (Daivobet®) and scalp (Xamiol®) application [1]. For localized foci, corticosteroids can also be applied occlusively to enhance efficacy, e.g. in the form of a patch (Betesil®).

In principle, uninterrupted corticosteroid therapy beyond one month is not recommended, partly because of atrophy and other cutaneous side effects, and partly because of absorption and risk of adrenocortical atrophy. As an alternative to corticosteroid preparations, the topical calcineurin inhibitors tacrolimus or pimecrolimus (Protopic®, Elidel®) are suitable in the intertriginous areas (psoriasis inversa).

Phototherapy

Phototherapy has a high value in the therapy of moderate and severe psoriasis. It is easy to use, cosmetically acceptable, not very costly and inexpensive. Finally, it can be advantageously combined with topical treatments. Today, UVB lamps emitting 311 nm are mainly used [2]. Longer wavelength UVA rays can also be highly effective in combination with photosensitizing psoralenes and retinoids [3].

Systemic therapy

Systemic therapies are indicated for moderate to severe cases of psoriasis that cannot be adequately controlled by local measures and phototherapy, and for psoriatic arthritis. A distinction is made between standard systemic therapies with methotrexate, acitretin, ciclosporin A and the fumaric acid esters and treatment with the newer biologics.

Methotrexate (MTX) is a cost-effective option with limited long-term prospects, however. Low dose (7.5 to max. 30 mg/week), MTX shows particularly good efficacy in all pustular forms of psoriasis, psoriatic erythroderma, and psoriatic arthritis, but also in extensive plaque psoriasis. MTX has an antiproliferative and anti-inflammatory effect by inhibiting the enzyme dihydrofolate reductase, thereby preventing the formation of the important metabolite tetrahydrofolic acid from folic acid. It leads to a 75% improvement in surface psoriasis in approximately 60% of cases (60% PASI75) [4,5]. A response is seen within two to six weeks [6]. Initial administration is 7.5 mg/week; parenteral form is preferred due to variable absorption kinetics with oral administration. Within the first two weeks, the dose should be increased to the normal maintenance dose of 10-15 mg weekly, adjusting the dose every three to four weeks. Administration of 5 mg folic acid p.o. 24-48 hours later improves tolerability. The main disadvantage of MTX is the limited cumulative dose of approximately 1.5 g, which is typically reached after two to four years. At this borderline, procollagen III determinations or liver biopsies are now recommended to exclude liver fibrosis.

The retinoids are analogues of the vital fat-soluble vitamin A. They have an antiproliferative and immunomodulatory effect. The most commonly used systemic retinoid, acitretin (Neotigason®), at a dosage of 20-75 mg, shows a PASI75 in 25-41% of patients within eight to twelve weeks [7,8]. Lower doses show no effect. Acitretin is preferred for pustular forms of psoriasis and psoriatic erythroderma. The initial dose is usually 0.5-1 mg/kg/d. After response, can be reduced to 0.3-0.5 mg/kg/d as maintenance therapy. Because frequent, though usually reversible, side effects occur and the drug is inferior to other preparations as a monotherapeutic, it is used almost exclusively as a combination preparation for photochemotherapy. Remission rates of over 94% are achieved here [3]. In any case, patients must be advised of the teratogenic effect and effective anticonception is mandatory for two years.

The enteric peptide ciclosporin A (Sandimmun Neoral®), derived from the soil mold Tolypocladium inflatum, inhibits nuclear transcription factors in T cells. Thus, rapid cellular immunosuppression is achieved. With oral administration of 2.5-3 mg/kgKG/d in two single doses (lowest described dosage for long-term treatment [9,10]), a PASI75 is achieved in 50-70% of cases after 8-16 weeks of therapy [11,12]. Ciclosporin A has the disadvantage of many side effects, including the development of arterial hypertension, renal insufficiency, tremor, infections, and hypertrichosis. In most cases, it cannot be used for more than a few months, so it is usually not suitable as a long-term therapy for psoriatic patients. Today, it is primarily used as a rescue therapy in situations where the skin status needs to be improved rapidly (within four weeks), such as in psoriasis erythrodermatica.

Since their development by Schweckendiek, a chemist himself affected by psoriasis, the fumaric acid esters (Fumaderm®) have proven their efficacy in double-blind studies [13–15]. This class of compounds is a by-product in the citrate cycle and has the advantage of a very safe efficacy profile, although it often presents with troublesome side effects at the start of therapy, e.g., flushing, headache, nausea, diarrhea, and passive lymphopenia. However, if tolerated, it can be taken for decades and completely suppress psoriasis. PASI75 is achieved by 50-70% of patients after 16 weeks [13–15]. It is not approved in Switzerland, but can be obtained easily from international pharmacies after obtaining approval from the health insurance company.

Biologics

Since psoriasis is considered a T-cell mediated immune disease in which cytokines also play an essential role, specific targets for therapy arise. The biologics, namely recombinant antibodies or soluble receptors, can effectively inhibit T cell-activating cytokines. Currently approved in Switzerland for the treatment of moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in adults under certain conditions are the tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α antagonists infliximab (Remicade®), etanercept (Enbrel®) and adalimumab (Humira®), the IL-12/23 blocker ustekinumab (Stelara®) and the IL-17A antagonist secukinumab (Cosentyx®).

TNF-α antagonists: The biologics currently most commonly used for the treatment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis are the TNF-α antagonists.

Etanercept (Enbrel®) is a soluble TNF-α receptor administered s.c.. One uses 50 mg weekly, or 50 mg twice weekly for severe cases. The drug leads to a 75% improvement in PASI in 30% of patients within twelve weeks [16]. It is the only biologic also approved for pediatric psoriasis [17]. The question for the future, especially for psoriatic arthritis in childhood, is to what extent early treatment with etanercept can prevent a destructive and invalidating course.

Infliximab (Remicade®) is a chimeric mouse-human antibody against TNF-α, which is administered as an infusion every eight weeks after initial up-dosing. Infliximab is suitable for severe patients because it can be given in a weight-adapted manner. Currently, it is one of the most effective biologics, but has the disadvantage of a decreasing effect over time due to antibody formation.

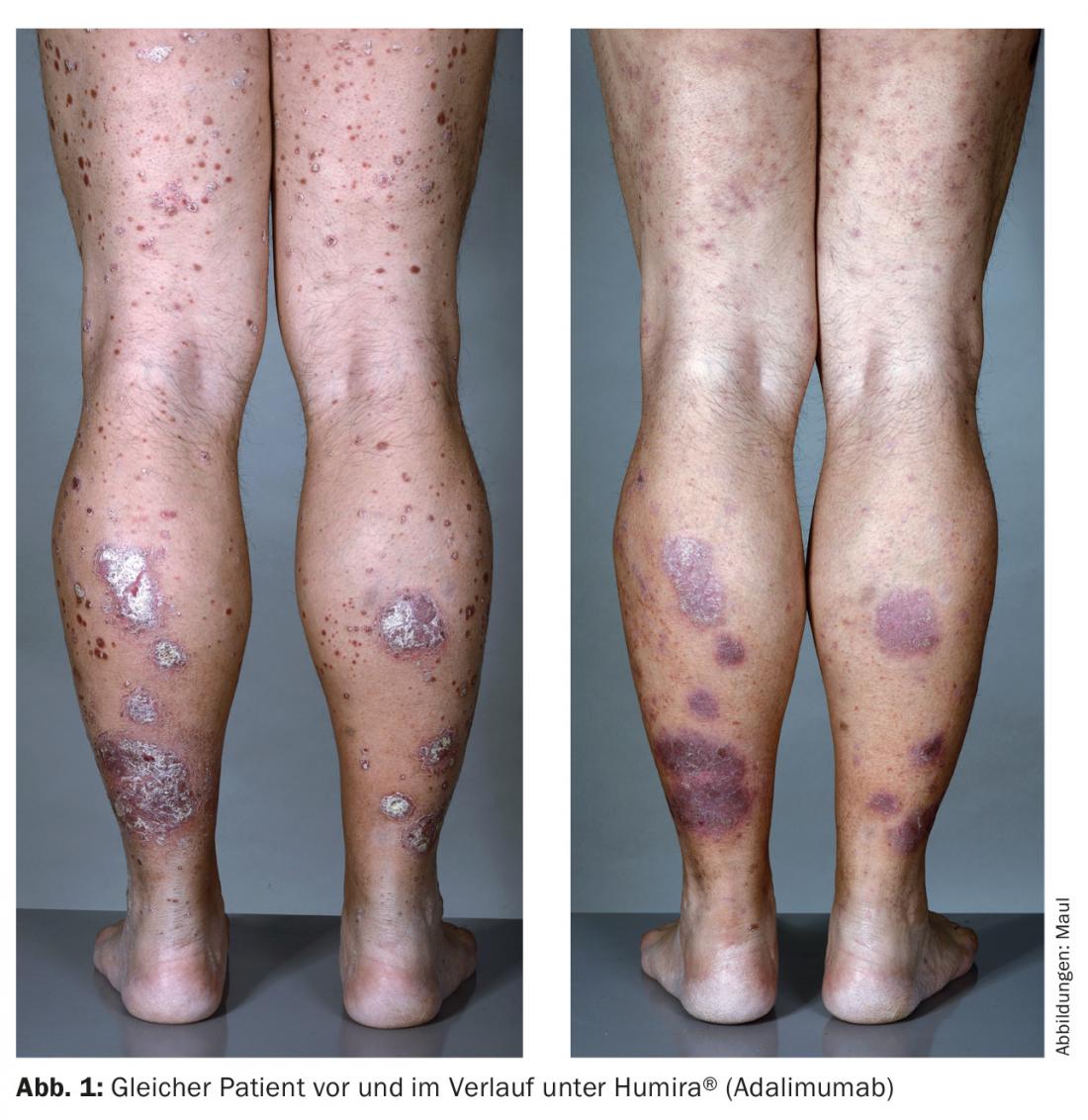

Adalimumab (Humira®) is a fully humanized TNF-α antibody that is injected s.c. every two weeks and combines good efficacy with great patient autonomy (Fig. 1). Both infliximab and adalimumab are superior to etanercept in efficacy.

IL-12/23 blocker: The IL-12/23 blocker ustekinumab (Stelara®) is a fully humanized antibody that binds the common subunit of IL-12 and -23. These cytokines are important in local immune responses. Although indispensable for the development of psoriatic skin lesions, they do not appear to be essential for normal immunity, as no significant adverse effects have been reported in studies compared with placebo. Long-term studies also showed no increased infection rates, making the drug one of the safest psoriasis therapies available [18,19].

IL-17A antagonist: A new biologic launched in 2015 is the IL-17A blocker secukinumab (Cosentyx®). IL-17A is a messenger produced by the T helper cell subset Th17, among others, and is very specifically responsible for local inflammation by locally recruiting neutrophil granulocytes and monocytes to sites of inflammation. The advantage of this selective inhibition of the immune response is that side effects are limited due to the inhibition of these cytokines. Secukinumab is administered 300 mg s.c. weekly within the first month, with monthly application starting at week 5. Two phase III trials of secukinumab in moderate-to-severe psoriasis showed that PASI75 improvement at week 12 of psoriasis therapy (compared to pre-therapy condition) was achieved in 77.1-81.6% of all patients [20]. A comparative study was conducted against treatment with etanercept; here, with etanercept, only 44.0% of patients achieved a PASI75 by week 12, while placebo achieved this endpoint in less than 5% of cases, respectively. By week 52, a PASI90 response was seen in 39% of patients on Enbrel® vs. 70.6% on secukinumab 300 mg. The side effects of IL-17 antagonists have been studied in phase III trials [20]. The drug showed a similar safety and side effect profile as the older biologics. Compared with placebo, the induction period showed a slightly increased incidence of adverse effects, especially those of a non-dangerous infectious nature. IL-17 plays a key role in the defense against mucocutaneous microbial pathogens. These are defended against, among others, by neutrophil granulocytes, for which IL-17-A plays an important role in migration and granulopoiesis. This explains why the incidence of uncomplicated Candida infections is increased in a dose-dependent manner. All Candida infections could be treated with standard therapeutics and did not result in interruption of biologics therapy. In addition, there were some neutropenias, but they resolved spontaneously.

Studies have shown that secukinumab is also a good alternative therapy for psoriatic arthritis. The endpoint used is ACR20, a standard score that measures 20 percent improvement in psoriatic arthritis symptoms. By week 24, this reached approx. 50% of secukinumab-treated compared to 18% of placebo patients. In a second study, 39% of patients treated with 300 mg secukinumab achieved an ACR20 compared with 15% of the placebo group [21].

Small Molecules

Another drug approved in Switzerland in 2015 is apremilast (Otezla®), an oral small molecule phosphodiesterase 4(PDE4) inhibitor for the treatment of psoriasis (PsO) and psoriatic arthritis (PsA), which belongs to the group of “small targeted molecules”. The PDE4 inhibitor apremilast intracellularly regulates the production of inflammatory cytokines, which play a role in the immunopathophysiology of PsO, through intracellular cAMP level elevation. The production of proinflammatory cytokines (such as TNF-α, IL-23, IL-17) is reduced, while the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines is promoted. In the ESTEEM 1 and 2 studies, approximately six times more patients achieved a PASI75 response at week 16 with apremilast than with placebo (specifically, one-third of apremilast patients experienced a 75% improvement in psoriasis within 16 weeks). Response was maintained for 52 weeks. 22% of patients treated with apremilast also achieved almost complete healing of PsO after 16 weeks (sPGA: 21.7% vs. 3.9%). In addition, apremilast showed good results as early as week 16 in difficult-to-treat sites such as scalp (scPGA) and nail infestation (NAPSI). Itching decreased more during this time than with placebo, but again, individual biologics have a more rapid and possibly more potent effect. Quality of life improved clinically significantly compared with the placebo group (DLQI reduction ≥5: 70% vs. 34%) [22]. Apremilast treatment was well tolerated (no increased risk of infection) and accordingly resulted in a lower rate of treatment discontinuation. Side effects experienced included: Diarrhea, nausea, headache, and upper respiratory tract infections, mostly within the first two weeks of treatment. Diarrhea symptoms generally resolved without medical intervention within four weeks with continued Otezla® therapy [22,23]. Apremilast is increased initially as a titration for five days (titration pack of 10/20/30 mg), then administered as maintenance therapy at 30 mg 2×/d. Likewise, apremilast can be used to treat psoriatic arthritis, as demonstrated in the PALACE1 study (n=504). Treatment with apremilast resulted in a significantly higher ACR20 response at week 16 compared with placebo (38.1% vs. 19.0%). ACR20 response rates improved progressively between week 24 and week 52 to 63% (apremilast 20 mg BID) and 55% (apremilast 30 mg BID), respectively. Apremilast also showed significant improvement in symptoms of PsA (swelling, pain, enthesitis, dactylitis), physical functioning, and quality of life (SF36, HAQ-DI). Improvements in relevant parameters were maintained through week 52 [23].

Outlook

With advances in immunology in understanding the pathogenesis of psoriasis, the development of drugs with increased selectivity, and the recognition of the systems nature of psoriasis, therapy has improved. At the same time, it became more complicated. In particular, the integration of biologics and small molecules in the treatment of severe psoriasis has led to a paradigm shift in dermatology: The skin is now again part of the whole body, which is equally affected by psoriasis in the area of the psyche, the cardiovascular system or the musculoskeletal system as the integument. Not least as a result of the clinical trials of biologics, attention to quality-of-life measurement tools as another measure of treatment success increased. We are extremely excited to see to what extent the use of biologics will have a favorable impact on comorbidities and life expectancy in the longer term as well. Whether in the clinic or dermatological practice: the decisive factors in each individual case are the medical indication and the lack of less expensive genuine therapeutic alternatives. Psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis should be treated by a team consisting of dermatologists, rheumatologists and primary care physicians.

It is of great importance to identify both the skin manifestations of psoriasis and the psoriasis comorbidities early and to treat them effectively.

Literature:

- Jemec GB, et al: A new scalp formulation of calcipotriene plus betamethasone compared with its active ingredients and the vehicle in the treatment of scalp psoriasis. A randomized, double-blind, controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol 2008; 59: 455-463.

- Barbagallo J, et al: Narrowband UVB phototherapy for the treatment of psoriasis. A review and update. Cutis 2001; 68: 345-347.

- Saurat JH, et al: Randomized double-blind multicenter study comparing acitretin-PUVA, etretinate-PUVA and placebo-PUVA in the treatment of severe psoriasis. Dermatologica 1988; 177: 218-224.

- Heydendael VM, et al: Methotrexate versus cyclosporine in moderate-to-severe chronic plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med 2003; 349: 658-665.

- Nyfors A: Benefits and adverse drug experiences during long-term methotrexate treatment of 248 psoriatics. Dan Med Bull 1978; 25: 208-211.

- Trüeb RM: Consensus recommendations methotrexate. Gebro Pharma 2008.

- van de Kerkhof PC, et al: The effect of addition of calcipotriol ointment (50 micrograms/g) to acitretin therapy in psoriasis. Br J Dermatol 1998; 138: 84-89.

- Gupta AK, et al: Side-effect profile of acitretin therapy in psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol 1989; 20: 1088-1093.

- Griffiths CE, et al: Clearance of psoriasis with low dose cyclosporine. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1986; 293: 731-732.

- Lowe NJ, et al: Long-term low-dose cyclosporine therapy for severe psoriasis. Effects on renal function and structure. J Am Acad Dermatol 1996; 35: 710-719.

- Koo J: A randomized, double-blind study comparing the efficacy, safety and optimal dose of two formulations of cyclosporine, Neoral and Sandimmun, in patients with severe psoriasis. OLP302 Study Group. Br J Dermatol 1998; 139: 88-95.

- Laburte C, et al: Efficacy and safety of oral cyclosporin A (CyA; Sandimmun) for long-term treatment of chronic severe plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol 1994; 130: 366-375.

- Altmeyer PJ, et al: Antipsoriatic effect of fumaric acid derivatives. Results of a multicenter double-blind study in 100 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol 1994; 30: 977-981.

- Gollnick H, et al: Topical calcipotriol plus oral fumaric acid is more effective and faster acting than oral fumaric acid monotherapy in the treatment of severe chronic plaque psoriasis vulgaris. Dermatology 2002; 205: 46-53.

- Altmeyer P, Hartwig R, Matthes U: [Efficacy and safety profile of fumaric acid esters in oral long-term therapy with severe treatment refractory psoriasis vulgaris. A study of 83 patients]. Dermatologist 1996; 47: 190-196.

- Gottlieb AB, et al: A randomized trial of etanercept as monotherapy for psoriasis. Arch Dermatol 2003; 139: 1627-1632; discussion 32.

- Paller AS, et al: Etanercept treatment for children and adolescents with plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med 2008; 358: 241-251.

- Leonardi CL, et al: Efficacy and safety of ustekinumab, a human interleukin-12/23 monoclonal antibody, in patients with psoriasis: 76-week results from a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (PHOENIX 1). Lancet 2008; 371: 1665-1674.

- Papp KA, et al: Efficacy and safety of ustekinumab, a human interleukin-12/23 monoclonal antibody, in patients with psoriasis: 52-week results from a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (PHOENIX 2). Lancet 2008; 371: 1675-1684.

- Langley RG, et al: Secukinumab in plaque psoriasis-results of two phase 3 trials. N Engl J Med 2014; 371: 326-338.

- McInnes IB, et al: Efficacy and safety of secukinumab, a fully human anti-interleukin-17A monoclonal antibody, in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriatic arthritis: a 24-week, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase II proof-of-concept trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2014; 73: 349-356.

- Papp K, et al: Apremilast, an oral phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitor, in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. Results of a phase III, randomized, controlled trial (Efficacy and Safety Trial Evaluating the Effects of Apremilast in Psoriasis [ESTEEM] 1). J Am Acad Dermatol 2015; 73: 37-49.

- Schafer PH, et al: The pharmacodynamic impact of apremilast, an oral phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor, on circulating levels of inflammatory biomarkers in patients with psoriatic arthritis. Substudy results from a phase III, randomized, placebo-controlled trial (PALACE 1). J Immunol Res 2015; 2015: 906349.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2016: 26(2): 10-16