Tic disorders are common chronic conditions of childhood. The course is favorable in most cases. Psychoeducation leads to significant relief. Treatment is indicated for more severe tics or noticeable psychosocial impairment.

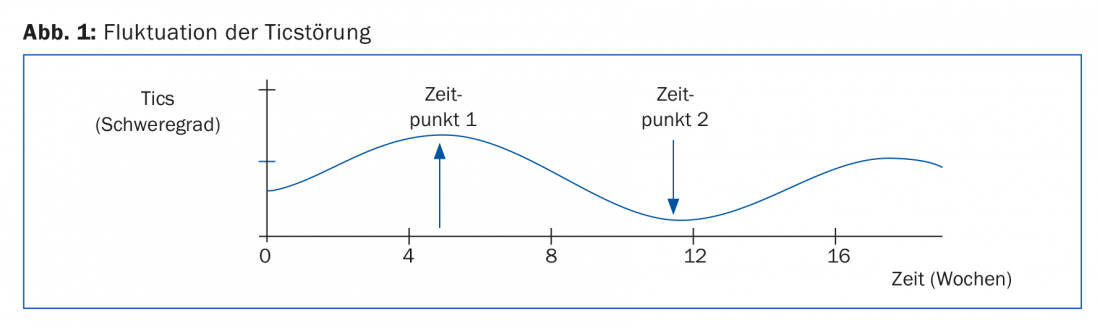

Tics are short, sudden, repetitive, non-rhythmic movements or sounds. Unlike compulsions, they are experienced as involuntary and senseless, and their suppression is usually accompanied by an increase in arousal. A distinction is made between simple and complex motor or vocal tics. Fluctuations in frequency and pattern over hours, days, weeks and months are a typical feature of tics (Fig. 1). This fact must be taken into account when assessing any intervention. In most cases, tics are preceded by an unpleasant sensory-motor urge sensation. This premonitory urge is experienced by many sufferers as more unpleasant than the tic itself and has been shown to impair quality of life. Pre-sense occupies a central position in behavioral treatment such as Habit Reversal Training (HRT) or Exposure and Response Prevention (ERP).

Normally, tics are not experienced as something that can be influenced or controlled at will. However, as the disorder progresses, many children and adolescents learn to suppress their tics for varying lengths of time. Strains, emotional arousal and stress or even joy can situationally intensify tics. They become less frequent when concentrating on a specific activity or through relaxation or distraction, and in most cases tics subside during sleep [1].

Frequency

Up to 12% of children and adolescents of primary school age are affected by transient tic disorder cross-culturally and worldwide. In 3-4%, symptoms remain chronically persistent. If chronic motor and vocal tics are present simultaneously and persist for more than twelve months, the diagnosis is Tourette’s syndrome, the prevalence of which is about 1%. Boys are four times more likely to be affected than girls and are also more likely to suffer from concomitant externalizing behavioral problems. Girls are more likely to be affected by comorbid obsessive-compulsive symptoms.

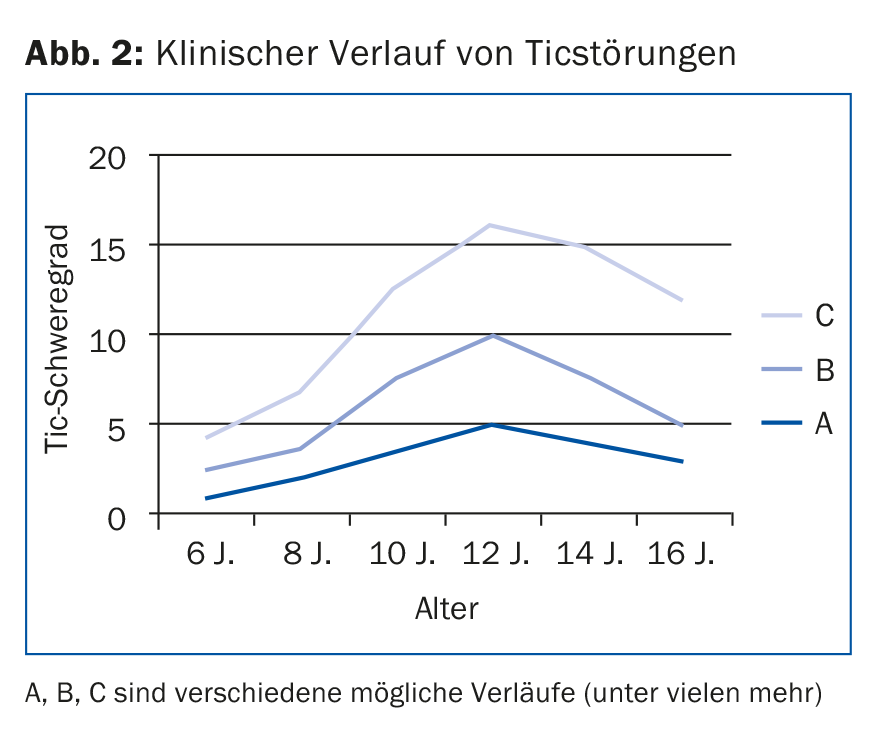

The severity of a tic disorder increases markedly in most sufferers between the ages of five and ten. In most cases – regardless of treatment – the course in adolescence is characterized by a decrease in symptoms (Fig. 2). Brain maturation during development improves impulse control, resulting in lower prevalence rates in adulthood [2].

Comorbidities

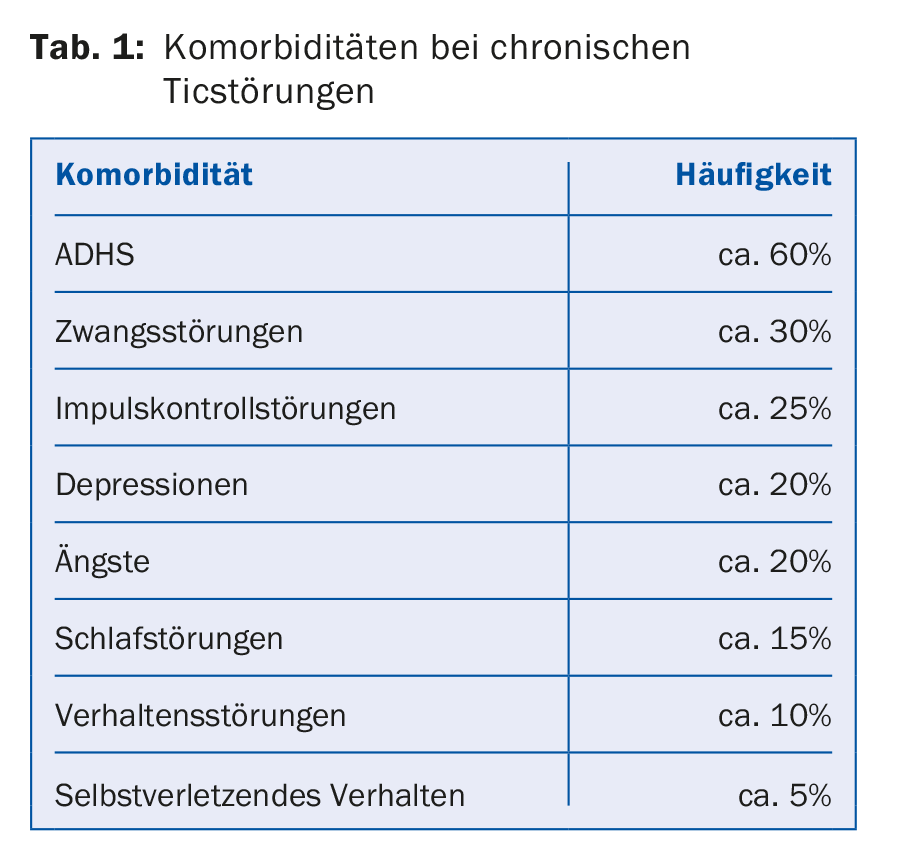

Neuropsychiatric comorbidities exist in 20-75% of chronic tic disorders; in patients with Tourette syndrome, they are the rule in 80-90% of cases. The course and severity of the accompanying disorders affect patients more than the tics and are a greater risk factor for development. The most common comorbidities are ADHD and obsessive-compulsive disorder (Table 1).

Causes

The causes of tic disorder as an organic, non-psychological disorder have not yet been conclusively clarified. A multifactorial model is assumed, which includes interactions between genetic, neurobiological, psychological, and exogenous influences. It is likely that the predisposition to tic disorder is genetic, whereas the severity and course of the disorder are determined by epigenetic factors such as complications during pregnancy, psychosocial stress, or immunological factors. The prominent role of the dopaminergic system in the pathogenesis of tic disorders is undisputed, with functional overactivity or hypersensitivity of dopamine metabolism suspected.

Diagnosis and assessment of severity

Clarification and diagnosis of tic disorders often take place years after the onset of symptoms and, as initial measures, can already provide considerable relief for those affected and their parents. The diagnosis is made clinically by a detailed child and adolescent psychiatric evaluation. In addition to exploration of the tics, any comorbidities should be recorded and other movement disorders (such as stereotypies, choreatic disorders, dyskinesias, restless legs syndrome, or functional movement disorders) should be excluded [3].

Treatment

The indication for treatment depends on the severity of the disorder and the perceived psychosocial impairment of the affected person and his social environment. In many cases, a tic disorder runs a mild course, so that it is not recognized at all or causes hardly any suffering. Often, education and counseling about the disorder (psychoeducation) by parents, child, teachers, and social environment are sufficient to counteract worries and adverse environmental reactions [1]. A “watch and wait” strategy with follow-up after six or twelve months is recommended. According to European clinical guidelines [4], treatment is recommended for severe tics or concomitant disorders. The type and severity of tics, subjective and psychosocial distress, limitations in functional level, and lack of sufficient self-control and coping mechanisms influence the choice of therapy. Depending on severity and comorbidities, treatment is either behavioral, medications, or a combination of these treatment options. None of the available therapies can cure tic disorder or influence its causes and spontaneous course.

Behavioral Therapy

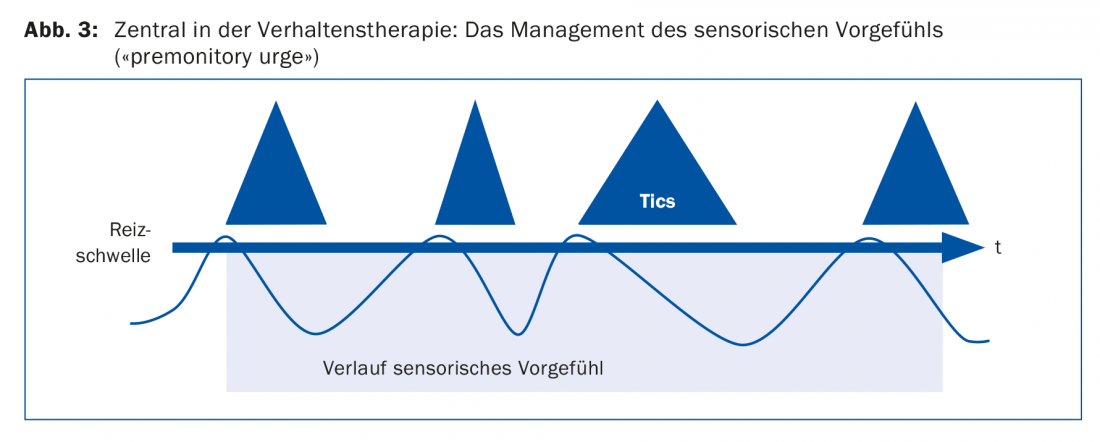

The core element of behavioral therapy for tic disorders is Habit Reversal Training (HRT) [5]. It assumes that behavioral habits become problems when they are partially unconscious, socially tolerated, and maintained through constant repetition. In HRT, the patient learns to interrupt them and replace the tics with consciously performed behaviors, which improves self-control. Through sensory-motor precognition training, patients learn to attenuate or prevent the tic with counter-regulation (Fig.3). Contrary to earlier assumptions, prolonged suppression of tics is not followed by increased “rebound”, especially if the patient is supported in suppressing the tics by ongoing reinforcement and by accompanying relaxation techniques [6].

In line with the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder, exposure with response prevention (ER) has recently been used for tic disorders [7]. Pre-feeling takes on a special position in this process. ER understands tics as habituated responses to the aversive pre-feelings. The goal is to suppress all currently present tics simultaneously and for as long as possible. Focusing on dealing with the disturbing pre-existing sensation makes it easier to refrain from tics. Elements from Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) and respiratory therapy can also helpfully support behavioral therapy. However, behavioral therapy treatment requires regular training in everyday life and a high level of self-motivation.

The good evidence of behavioral therapy (HRT and ER) for tic disorders is now supported by randomized controlled trials [7,8]. The European clinical guidelines [4] recommend behavioral therapy for TS and other tic disorders as the method of first choice. Studies comparing the efficacy of behavioral therapy and medication for tic disorders are still lacking. Nevertheless, due to better long-term effects and fewer side effects, it is recommended to start treatment with psychoeducation and behavioral therapy (HRT and ERP).

Despite the available evidence for behavioral therapy for tic disorders, these procedures are still used far too infrequently by psychiatrists and psychologists in Europe and the United States. Many clinicians barely know HRT or do not feel competent enough to use it. E-health could be one possible way to address this challenge. Several research groups are investigating the effectiveness of video and web-based behavior therapy applications [9]. Specific smart phone apps can also help disseminate and support therapy for affected youth.

Drug treatment

If there is a massive and multifaceted tic symptomatology with comorbidities, the child’s or adolescent’s compliance for behavioral therapy usually decreases. Pharmacotherapy is indicated for severe and chronic tic disorders that significantly impair the quality of life of children and adolescents (e.g., through social isolation and stigmatization, and reductions in school performance). Low-dose atypical neuroleptics are the drugs of first choice in Europe and are administered “off-label”, although few controlled studies are available for this indication [10]. Haloperidol is approved, but it is rarely used anymore because of side effects. Tiapridal®, a selective antagonist for dopamine D2 receptors, has long been the drug of choice in children in Switzerland and Germany. Clinical experience regarding efficacy and tolerability is very good. An increase in serum prolactin and very rarely the development of galactorrhea should be noted. Aripiprazole, a promising newer neuroleptic and partial dopamine D2 receptor agonist, has been shown to be effective at a low dose (2.5-5 mg/d, max. 7.5 mg/d) showed good efficacy and only minor side effects [11]. It is administered “off-label.”

Risperidone is no longer used as the first choice in German-speaking countries despite a good efficacy-side-effect profile in children. It must be used at an antipsychotic effective dose or extrapyramidal and metabolic side effects will occur (<3-4 mg/d).

In the United States, clonidine and guanfacine, alpha-2-adrenergic agonists, are also used in the treatment of tic disorders with good efficacy.

In the case of tic disorders, medication should be planned over a longer period of time; doses and discontinuation should be done in small steps. Neither improvements nor deteriorations should trigger a too rapid discontinuation attempt, since the symptomatology, as already described, fluctuates spontaneously even without treatment.

Conclusion

The best possible psychotherapeutic and/or drug interventions can often achieve a substantial reduction in symptoms, although complete remission is not always achieved. The decisive factor for treatment is the level of suffering of the affected patients and their families. The goal of good counseling and treatment should in any case be to strive for a sufficient quality of life.

Take-Home Messages

- Tic disorders are among the common chronic disorders of childhood. The course is favorable in most cases. In adolescence, tics spontaneously resolve in 90% of patients.

- Comorbidities such as ADHD and compulsions are common in Tourette syndrome. They often affect quality of life more than tics and should also be treated as a priority.

- Psychoeducation about the disorder leads to significant relief for most families and patients. Treatment is indicated for more severe tics or noticeable psychosocial impairment.

- Behavioral therapy is usually recommended as the first-line treatment. It has good evidence and fewer side effects than medication.

- In cases of pronounced tic symptoms, treatment with atypical neuroleptics such as Tiapridal® or aripiprazole (“off-label”) is indicated.

Literature:

- Tagwerker-Gloor F: Tic disorders in childhood and adolescence. PSYCHup2date 2015; 9: 161-176.

- Leckman JF, Bloch MH, Scahill L: Phenomenology of tics and natural history of tic disorders. Advances in Neurology 2006; 99: 1-16.

- Cath DC, et al: European clinical guidelines for Tourette syndrome and other tic disorders. Part I: Assessment. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 2011; 20: 155-171.

- Verdellen CWJ, van de Griendt JMTM, Hartmann A: European clinical guidelines for Tourette syndrome and other tic disorders. Part III: behavioral and psychosocial interventions. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 2011; 20: 197-207.

- Azrin NH, Nunn RG: Habit reversal: A method of eliminating nervous habits and tics. Behaviour Research and Therapy 1973; 11: 619-628.

- Himle MB, Woods DW: An experimental evaluation of tic suppression and the rebound effect. Behaviour Research and Therapy 2005; 43: 1443-1451.

- van de Griendt JMTM, et al: Behavioural treatment of tics: Habit reversal and exposure with response prevention. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 2013; 37(6): 1172-1177.

- Piacentini J, et al: Behavior Therapy for Children With Tourette Disorder: A Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA 2010; 303(19): 1929-1937.

- Dutta N, Cavanna A: The effectiveness of habit reversal therapy in the treatment of Tourette syndrome and other chronic tic disorders: a systemic review. Functional Neurology 2013; 28: 7-12.

- Roessner V, Rothenberger A: Pharmacological treatment of tics In: Martino D, Leckman JF, editors. Tourette Syndrome. New York: Oxford Press 2013; 524-552.

- Ghanizadeh A, Haghighi A: Aripiprazole versus risperidone for treating children and adolescents with tic disorder: a randomized double blind clinical trial. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev 2014; 45: 596-603.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2017; 12(8): 25-28