Psychosocial factors are usually more important than organic factors for the different course forms and lengths of a whiplash injury. In the case of fresh whiplash injuries, factual clarification is therefore essential. Chronification must not be encouraged.

Hardly any other complaint is as controversial in terms of its genesis and its effects as the so-called “whiplash” or “whiplash injury”. “Distortion trauma of the cervical spine”. According to the pathodynamics, this is a sprain of the cervical spine caused by indirect force, whereby this soft tissue strain of ligaments, tendons and muscles occurs in the context of acceleration/deceleration, as is often the case in rear-end collisions in road traffic or also in sports accidents (martial arts, diving). In very severe cases, osseous or vascular lesions are also possible; however, in the vast majority of cases, this is not expected.

This form of trauma is extremely common: in Switzerland alone, approximately 25,000 cases are reported annually [1]. The prognosis seems to be only limitedly favorable: A chronification occurs – depending on the author – in 10% or even more of the affected persons. However, more profound studies report complete recovery in 97% of patients within one year [2]. Moreover, cross-national and cross-regional studies have shown massive differences in the prevalence of such sequelae: cultural perceptions and expectations regarding insurance benefits seem to play a substantial role.

Symptomatology and course

Undisputed is the symptom complex that can immediately follow a corresponding collision as a direct trauma consequence [3]:

- Neck, shoulder and arm pain

- Headache, predominantly occipital, with tendency to spread

- Unsystematic dizziness.

In addition, there may be further psychovegetative irritation symptoms in the sense of general disturbance of well-being. However, the possible latency period until the appearance of such symptoms is already disputed. It should be noted here that pain complaints in sprains follow relatively quickly on from the distortion trauma, all the more so as here the neck has to bear the entire weight of the head and there are few relief options. In this sense, even a symptom-free interval of more than 24 hours is dubious; one of more than 72 hours can hardly be explained medically. If symptoms are still reported after six months, the condition is referred to as “chronic whiplash disease” or “pseudoneurasthenic syndrome after cervical spine distortion” (“late whiplash syndrome”). These include the following symptoms [3]:

- Rapid exhaustibility

- Daytime sleepiness

- Sleep disorders

- Fear

- Dizziness

- Noise sensitivity

- Irritability

- Decreased resilience

- Cognitive disorders.

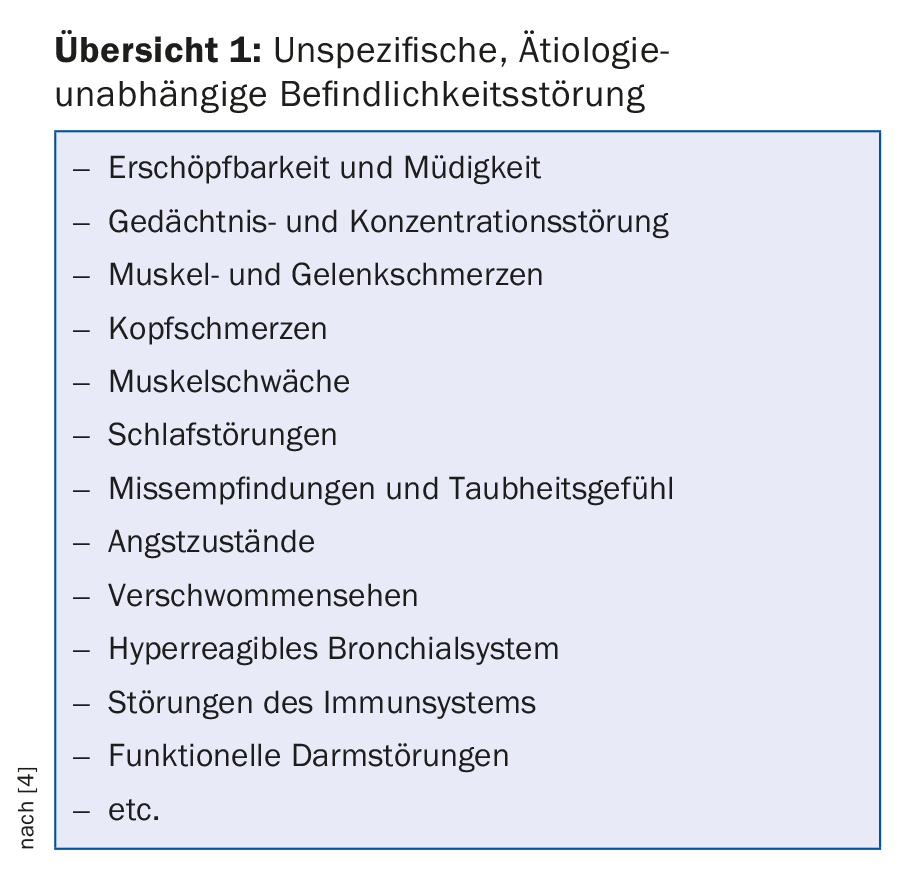

This symptomatology is strikingly reminiscent of the symptom complex described by Widder [4] as a “nonspecific, i.e. etiology-independent mood disorder” (overview 1).

However, it is now clear that the Swiss Federal Court defined a completely unspecific discomfort as an allegedly disturbance-proving long-term symptomatology in “whiplash” in the “Salanitri judgement” of 1991.

In view of these broadly overlapping symptom complexes, the impression arose that there is no nosological delimitability here and that these chronic symptoms after “whiplash” trauma can be equated with somatoform disorders (BGE 9C_510/2009) and therefore do not per se entitle the patient to benefits.

About the genesis

To date, even state-of-the-art radiodiagnostics have failed to convincingly demonstrate any microlesions that could plausibilize these persistent long-term courses at the organic level. In contrast, psychosocially oriented medicine has come to recognize that the way in which the individual deals with his or her illness, i.e., his or her illness behavior, is of decisive importance. Such considerations have also been exhibited, for example, in mild traumatic brain injury and even in cancer. In order to concretize the problem of coping with disorders, it is necessary to resort to older concepts of medical sociology.

The sick role was conceived by Parsons [5] as an ideal-typical role expectation, as it is applied to the sick person by society and which aims in particular at the greatest possible damage limitation: The sick person is allowed to withdraw from work, but is required to seek treatment and to return to work as soon as possible. Mechanic [6], however, has shown in relation to illness behavior that the patient role can be shaped very differently in each individual, which in turn depends very much on personality variables such as age, gender, social background or cultural background.

“Abnormal sick leave behavior” is thus suboptimal patient behavior aimed at enjoying the privileges of sick leave longer than necessary and staying away from the service area for longer or permanently. This can then result in social illness gains (financial compensation and compassionate care) that cement the patient role, as it were. In a previous paper [7] on dysfunctional complaint coping, it is shown that abnormal illness behavior may be associated with a number of illness phenomena that, although not illness value per se, nevertheless massively complicate work integration, such as aggravation, self-limitation, catastrophizing, deconditioning, symptom expansion, personality regression, subjective performance insufficiency, and final compensation attitude.

From time to time, disastrous courses are observed, which can be made understandable with the explanatory model of the invalidation process by Weinstein [8]. According to this author, psychosocial problems that put a strain on self-esteem, such as a job overload or an unexpected layoff, are at the beginning. A health disorder, such as one caused by an accident, can then legitimize an exit from the benefit area. State and family support measures stabilize the existence and the psyche of the affected person, but also confirm him in his role of illness, which in turn promotes chronification.

Conclusions

The aim of patient management should be to prevent all these chronification processes with their economically damaging consequences, which can be done primarily through secondary prophylaxis. Unambiguous patient education about the nature and favorable prognosis are paramount. Furthermore, therapeutic measures in the early phase should be limited to a reasonable minimum: analgesics, active exercise, only a short rest period, no Schanz collar, especially since the latter can even contribute to the weakening and stiffening of the neck muscles. In the case of emerging long-term courses, the psychosocial conditions (family and occupational stress factors, maladaptive disease processing, etc.) must be focused on accordingly.

Take-Home Messages

- Whiplash is usually a soft tissue strain in the cervical spine. The prognosis is therefore similar to that of a sprain, i.e. good.

- The different forms and lengths of progression are caused less by organic factors than by psychosocial factors (quality of disorder processing).

- In the case of recent whiplash injuries, it is essential to provide factual information and to avoid anything that could promote an unnecessary protective posture and thus chronification.

Literature:

- Knecht T: Distorsion trauma of the cervical spine – A status review from a psychiatric perspective. Switzerland Med Forum 2011; 11(19): 314-318.

- Spitzer WO, et al: Scientific Monograph of the Quebec Task Force on Whiplash Associated Disorders cohort study: Redefining “Whiplash” and its management. Spine 1995; 20: 1-73.

- Hausotter W: Assessment of somatoform and functional disorder. 2nd ed. Munich: Urban and Fischer 2004.

- Aries B: Pain syndromes and mood disorders. In: Rauschelbach HH, et al. (Ed.): The neurological report. Stuttgart: Thieme 2000; 422-444.

- Parsons T: The social system. New York: Free Press of Glencoe 1951.

- Mechanic D: The concept of illness behavior. J Chron Dis 1962; 13: 189-194.

- Knecht T: When the pain patient does not work – phenomena of dysfunctional complaint management as obstacles to rehabilitation. Switzerland Med Forum 2008; 8(42): 797-802.

- Weinstein MR: The concept of the disability process. Psychosomatics 1978; 19: 94-97.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2017; 12(10): 12-14